A day late, but better late than never, yeah?

-----------------------------------------------

Noah Noble, re-elected by a wide margin (having secured 23.7% more of the popular vote than his next closest opponent), took the election of 1840 to be a mandate to continue to promote Whig policies. 1841 was a Whig year - Whigs were sitting in most of the gubernatorial positions, the US House was overwhelmingly Whig, and the Senate was Whig by a five vote margin. Noble's first act of his second term was to urge Congress to pass tax breaks on the poor and middle class, which was done in late November. The new tax structure was as follows: the wealthy paid 33%, the middle class paid 28.9%, and the poor paid 28.1%, some of the world's lowest tax rates. Noble hoped that the low taxes would encourage immigration, especially from Ireland, Poland, and the various German and Italian states. The Democrats did not voice any real opposition to the tax cuts, but the Liberty Party, led by Martin van Buren (although its most prominent congressional member was Johns Hopkins, of Maryland, an outspoken abolitionist and philanthropist) voiced concern that the tax burden was somewhat unfair, as the wealthiest Americans were paying only a 5% percentage more than the poorest.

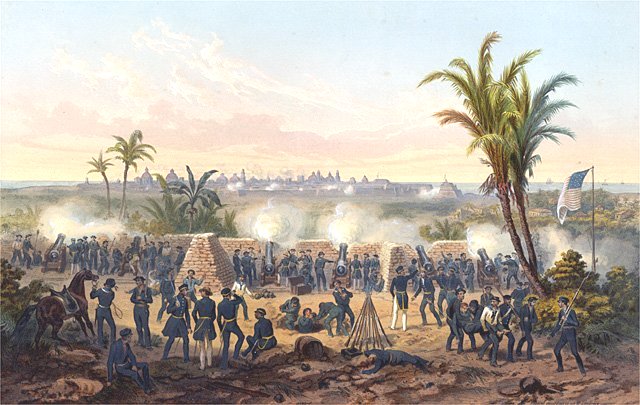

Meanwhile, tensions were high in American Venezuela, where the US forces stationed to protect the US property there were constantly facing belligerent mobs armed with rocks, bottles, and bricks. Things reached a breaking point in January of 1842, when soldiers opened fire on a man they believed was attempting to set the barracks on fire. His death led to outrage in Coro, and an armed uprising against US forces began. The revolt was easily quashed, but Noble was rattled by it, the first real internal threat America had faced in decades, even if it was just a colonial uprising.

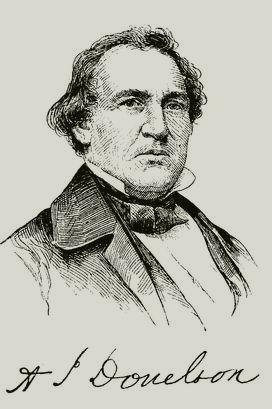

Noble felt the need to appoint a strong governor to American Venezuela, someone who would be able to maintain order and provide a valuable link between the White House and the local government in the colony. After much discussion with his cabinet, he settled on Millard Fillmore, a forty two year old New Yorker with a reputation for being a tough legislator and competent judge of character. Noble's decision was a clever political move, as well - despite being a Whig that usually voted the party line in House votes, Fillmore was known for his anti-Irish sentiments, something that did not sit well with Noble, given the push to attract immigrants to America. By giving Fillmore a lucrative post as a colonial governor, Noble removed an internal foe and strengthened his party's unity.

Millard Fillmore, colonial governor of American Venezuela

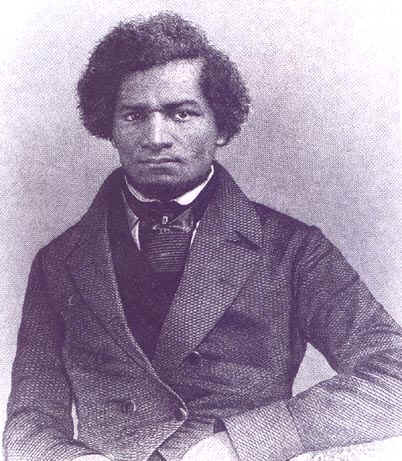

In May 1842, Noble again went to congress asking for support for a change in policy. This time he sought to raise the national tariff, an act he thought would supplement the treasury to make up for the lost money brought about by his tax cuts. He proved himself to be a capable compromiser - upon being rebuked by many in his own party, he turned to Johns Hopkins, the most prominent member of the Liberty Party in congress, and to James K Polk, an up and coming Democrat from North Carolina. The pair, along with Noble's VP, John Bell, sat down to work out a way to get the tariffs passed. An agreement was finally reached - the Liberty Party representatives would vote for the bill if taxes on the rich were raised by 1%, and Polk promised his party's support if he was appointed Minister Plenipotentiary to Texas, the highest diplomatic position in the US Embassy in Texas. Noble, upon being informed of the deal, agreed that it was unfortunate but approved of it. Enough Whigs were strong-armed into voting for it, and the tariff bill passed and was signed into law in May of 1842.

Johns Hopkins (Liberty Party) and James K Polk (Democratic Party)

Several months later, in March 1843, at the urging of Governor Fillmore, President Noble again went to congress, this time requesting funding to build forts in both provinces of American Venezuela, as well as money being set aside for the construction of a naval base in one of the two provinces upon the completion of the forts. Congress agreed, although many Democrats cried foul, arguing that it was a ploy to make the Whig party look strong on foreign policy matters when in reality they had just co-opted the Democratic plan for the war in the first place. Construction began as soon as the funds were appropriated and the building materials arrived in American Venezuela.

In late Spring 1843 the election campaign for 1844 kicked off. Noble announced that he would not run for a third term, maintaining the tradition set by George Washington of retiring after the second term. Interestingly enough, there were no clear frontrunners for the candidacy of either of the two major parties. Fillmore, Bell, and Clay were names that were floated by the Whigs, while the likes of Polk, Woodbury, and King were prominent Democrats likely to seek the nomination. Meanwhile, the Liberty Party was the only party secure in its candidate - Martin van Buren would not seek election as President, but would instead run in the New York gubernatorial election, leaving Johns Hopkins as the clear candidate.

The Whigs tremendous popularity (hovering around 60% in most opinion polls), was bad news for the Democrats and Liberty Party, and there was a general sense that the real election would be the Whig's nomination battle, with the winner being almost ensured victory in the general election. That being said, none of the other parties were willing to give up without a fight, and the stage was set for the election season of 1844.

-----------------------------------------------

Noah Noble, re-elected by a wide margin (having secured 23.7% more of the popular vote than his next closest opponent), took the election of 1840 to be a mandate to continue to promote Whig policies. 1841 was a Whig year - Whigs were sitting in most of the gubernatorial positions, the US House was overwhelmingly Whig, and the Senate was Whig by a five vote margin. Noble's first act of his second term was to urge Congress to pass tax breaks on the poor and middle class, which was done in late November. The new tax structure was as follows: the wealthy paid 33%, the middle class paid 28.9%, and the poor paid 28.1%, some of the world's lowest tax rates. Noble hoped that the low taxes would encourage immigration, especially from Ireland, Poland, and the various German and Italian states. The Democrats did not voice any real opposition to the tax cuts, but the Liberty Party, led by Martin van Buren (although its most prominent congressional member was Johns Hopkins, of Maryland, an outspoken abolitionist and philanthropist) voiced concern that the tax burden was somewhat unfair, as the wealthiest Americans were paying only a 5% percentage more than the poorest.

Meanwhile, tensions were high in American Venezuela, where the US forces stationed to protect the US property there were constantly facing belligerent mobs armed with rocks, bottles, and bricks. Things reached a breaking point in January of 1842, when soldiers opened fire on a man they believed was attempting to set the barracks on fire. His death led to outrage in Coro, and an armed uprising against US forces began. The revolt was easily quashed, but Noble was rattled by it, the first real internal threat America had faced in decades, even if it was just a colonial uprising.

Noble felt the need to appoint a strong governor to American Venezuela, someone who would be able to maintain order and provide a valuable link between the White House and the local government in the colony. After much discussion with his cabinet, he settled on Millard Fillmore, a forty two year old New Yorker with a reputation for being a tough legislator and competent judge of character. Noble's decision was a clever political move, as well - despite being a Whig that usually voted the party line in House votes, Fillmore was known for his anti-Irish sentiments, something that did not sit well with Noble, given the push to attract immigrants to America. By giving Fillmore a lucrative post as a colonial governor, Noble removed an internal foe and strengthened his party's unity.

Millard Fillmore, colonial governor of American Venezuela

In May 1842, Noble again went to congress asking for support for a change in policy. This time he sought to raise the national tariff, an act he thought would supplement the treasury to make up for the lost money brought about by his tax cuts. He proved himself to be a capable compromiser - upon being rebuked by many in his own party, he turned to Johns Hopkins, the most prominent member of the Liberty Party in congress, and to James K Polk, an up and coming Democrat from North Carolina. The pair, along with Noble's VP, John Bell, sat down to work out a way to get the tariffs passed. An agreement was finally reached - the Liberty Party representatives would vote for the bill if taxes on the rich were raised by 1%, and Polk promised his party's support if he was appointed Minister Plenipotentiary to Texas, the highest diplomatic position in the US Embassy in Texas. Noble, upon being informed of the deal, agreed that it was unfortunate but approved of it. Enough Whigs were strong-armed into voting for it, and the tariff bill passed and was signed into law in May of 1842.

Johns Hopkins (Liberty Party) and James K Polk (Democratic Party)

Several months later, in March 1843, at the urging of Governor Fillmore, President Noble again went to congress, this time requesting funding to build forts in both provinces of American Venezuela, as well as money being set aside for the construction of a naval base in one of the two provinces upon the completion of the forts. Congress agreed, although many Democrats cried foul, arguing that it was a ploy to make the Whig party look strong on foreign policy matters when in reality they had just co-opted the Democratic plan for the war in the first place. Construction began as soon as the funds were appropriated and the building materials arrived in American Venezuela.

In late Spring 1843 the election campaign for 1844 kicked off. Noble announced that he would not run for a third term, maintaining the tradition set by George Washington of retiring after the second term. Interestingly enough, there were no clear frontrunners for the candidacy of either of the two major parties. Fillmore, Bell, and Clay were names that were floated by the Whigs, while the likes of Polk, Woodbury, and King were prominent Democrats likely to seek the nomination. Meanwhile, the Liberty Party was the only party secure in its candidate - Martin van Buren would not seek election as President, but would instead run in the New York gubernatorial election, leaving Johns Hopkins as the clear candidate.

The Whigs tremendous popularity (hovering around 60% in most opinion polls), was bad news for the Democrats and Liberty Party, and there was a general sense that the real election would be the Whig's nomination battle, with the winner being almost ensured victory in the general election. That being said, none of the other parties were willing to give up without a fight, and the stage was set for the election season of 1844.