J.J.Jameson: Thanks. I was hoping someone would pick up on that. How Jackson is handling Vietnam is quite different from how JFK and LBJ did. Whether the outcome will be any better is anyone's guess.

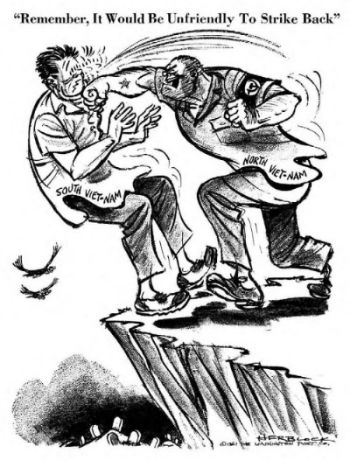

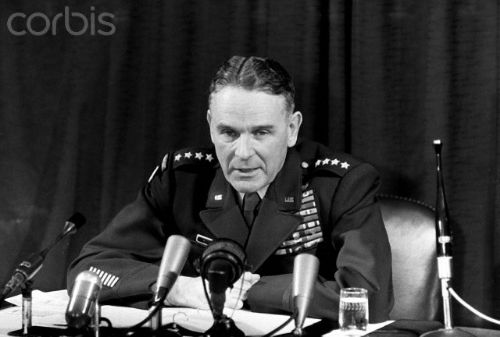

El Pip: Taylor really did recommend to JFK this plan to take the offensive with 40,000 troops. Kennedy rejected it because he was trying very hard not to commit substantial forces to Vietnam. JFK was never really comfortable with Vietnam and there's evidence to suggest that he was looking for a way out before his assassination.

Jackson, on the other hand, is way more hawkish that JFK was and is much more willing to give Taylor his backing. Thus the escalation decision LBJ historically made in 1965 happens three years earlier.

Kurt_Steiner: Houston to Kurt: we don't have a problem. You took the sentence out of context, that's all.

He confided to his speechwriter Arthur Schlesinger that he didn’t see how “American troops cannot be involved on the Asian mainland. It’s necessary for us to have a presence there.”

H.Appleby: I still don't understand the whole hashtag thing. Then again, never using Twitter might have something to do with that.

Kurt_Steiner: And now we have countries shutting down other countries' movie releases.

hmy:

SotV: Reading that reminds me of something a President Reagan aide said when the State Department was trying to override one of Reagan's decisions:

"Wait a minute! No one elected the State Department to anything! Those guys have been screwing up for twenty-five years!"

H.Appleby: Now that I think about it, I've been talking about Vietnam since Dewey's tenure. That is long.

hmy:

volksmarschall: As I read this, the Oliver Stone film "JFK" is playing in my head.

On a side note, I’m a little surprised no one – even volksmarschall – brought up the beginning of the update. Since I don’t know how far this AAR will go, every once in a while I like to give hints about the future. In this case, I wanted to reveal that George Bush will be President of the United States in 1987 instead of Ronald Reagan (I’m not entirely sure what I’m going to do with Reagan). Bush is one of my favorite Presidents and he’s definitely someone I want to put in the White House. I picked 1987 because it can either be his first term or second term, depending on whether I elect him in 1980 or 1984. I’m determined to make Bush a two-termer TTL, so he’ll either serve 1981-1989 or 1985-1993.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The United Nations Speech

By mid-March 1962, the Jackson Administration had its' hands full. The crisis in South Vietnam seemed to be getting worse with each passing day. Not helping matters any, clean-up was underway from North Carolina to Maine following a devastating and lingering nor’easter which had pummeled the East Coast with heavy flooding and strong winds. Busy as he was, the President chose this particular moment to pick a fight over an issue he felt strongly about. On March 20th, Scoop was scheduled to deliver a speech at the National Press Club in Washington. Founded in March 1908 by thirty-two newspapermen, every President since Theodore Roosevelt had visited the club for journalists. Jackson had been invited by the group to speak on any issue that he chose. In a surprise move, he decided to make the United Nations the subject of his speech. At the time, Congress was debating whether to approve the purchasing of bonds to help finance operations at the UN. It was a routine spending matter that not many people were paying much attention to. That would change however after Jackson mounted the podium at the National Press Club and gave what would be one of the defining speeches of his Presidency.

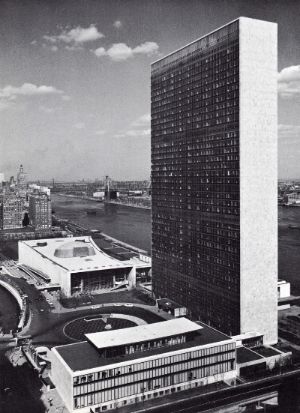

Once a supporter of the postwar international organization, Jackson had soured on the UN by the time he became President. Originally intended to be a forum in which countries could come to solve their problems peacefully, the UN had become polarized by the Cold War. The United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies were using the organization to trade verbal attacks and accusations. There seemed to be more talking than actual action at UN Headquarters in New York City. The United States Ambassador there, Dorothy Fosdick (the first woman to hold that post), was complaining that she was spending more time defending America from international attacks than she was exerting America’s leadership on the world stage. Believing the UN to be practically useless foreign policy-wise, Jackson had come to the conclusion that the strength and unity of the Atlantic community and NATO were far more important to America’s position in the world. He therefore pursued a foreign policy that put a greater emphasis on maintaining close relationships with individual allies like Canada and the United Kingdom at the expense of the collective global pool known as the United Nations. The problem was that not everyone shared his point of view. There were voices in America that were not only urging stronger cooperation with the UN at the expense of US interests but were actually advocating reforming foreign policy so it would be more aligned with UN interests. In other words, according to Jackson biographer Robert G. Kaufman, they wanted

“the United Nations to impinge on the roles of the President and the Secretary of State” in crafting how the United States handled her foreign affairs. This was wholly unacceptable to Jackson, who took advantage of his platform at the National Press Club to attack what he considered to be the wrong course of action to pursue. He would pull no punches.

What the audience heard was the strongest criticism ever leveled at the UN and its’ supporters by a President. Throughout the speech, Jackson warned against putting the UN in charge of formulating America’s foreign policy:

“The United Nations was never intended to be a substitute for our own leaders as the makers and movers of American foreign policy.”

Nor should

“our UN delegation in New York become forced to answer to a second foreign affairs office.”

Doing so would cause the United States to weaken its allies

“in deference to what is represented in New York as a world opinion.”

Although he emphasized that the United Nations

“should continue to be an important avenue of American foreign policy,” Jackson also said that

“the involvement of the United Nations has at times hampered the wise definition of our national interest and the development of sound policies for their advancement.”

He advised against holding an exaggerated view of the UN’s role, warning that it could

“imperil the ability of the United States in containing the Soviet Union and China, which are the paramount threats to our national interests.”

“The Soviet Union and China,” he went on to say,

“Are not and will not be peace-loving nations. The leaders of both nations have threatened to ‘bury’ us. In their more agreeable moments, the Russians and the Chinese promise to bury us nicely; but whatever their mood, the Earth will still be six feet deep above us. We must realize that the Soviet Union and China see the UN not as a forum of cooperation but as one more arena of struggle.”

He concluded:

“The hope for peace with justice does not lie with the United Nations. Indeed the truth is almost exactly the reverse. The best hope for the United Nations lies in the maintenance of peace. Peace depends on the power and unity of the Atlantic community and the skill of our direct diplomacy.”

The astounding speech made headlines around the world. Here was the President of the United States, the leader of the Free World, being openly critical of the United Nations and urging public opinion to be more educated about

“the direction of a more realistic appreciation of the United Nation’s limitations, more modest hopes for its accomplishments, and a more mature sense of the burdens of responsible leadership.”

The United Nations Speech as it would become known elicited strong reactions both at home and abroad. Abroad, the Soviets and the Chinese quickly attacked Jackson for making remarks that they considered to be reckless and bellicose. Even the United Kingdom, normally a close ally of the United States, disagreed with it. Prime Minister Rab Butler found the speech too strong and thought Jackson had been rash in his denouncement of the United Nations. The Prime Minister, being much more experienced in dealing with the world, felt that the President had made a terrible mistake in throwing the UN under the bus.

“I understand he’s frustrated,” Butler said in private,

“But there’s a right way and a wrong way to deal with frustration. He chose the wrong way.”

Taking a more moderate position, Butler publically re-affirmed his country’s

“fullest confidence” in the international organization and expressed his hope that whatever problems that existed there could be resolved peacefully and with a cool head. At home, the reaction to the controversial speech split largely along ideological lines. At home, the reaction to the controversial speech split largely along ideological lines. Scoop received the majority of his praise from conservatives and the majority of his criticisms from liberals. Democratic Senator Richard Russell of Georgia sent Jackson a message telling him that

“no finer, saner, or more historic speech on international relations has been made during my time here in Washington. It is refreshing to see someone admit that this country has rights that should be asserted out loud.”

Republican Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, whom Jackson could depend on to support him when it came to national defense and foreign policy issues, put in his two cents:

“The theory that the UN has preserved the peace is preposterous. We must not allow it to dictate our foreign policy.”

Secretary of Labor Ronald Reagan, who represented Conservative Democrats in the Administration, not only loved the speech but even urged Scoop to go one step further and

“get us the hell out of that kangaroo court and let it sink. That would send a message to those bums.”

Liberals, who were far more supportive of the UN than their right-wing counterparts, uniformly hated the speech and attacked the President for suggesting that the United States should disregard the United Nations when it comes to policy-making. Republican Senator Jacob Javits of New York, one of the most liberal Republicans in Congress, called the speech

“unfortunate”.

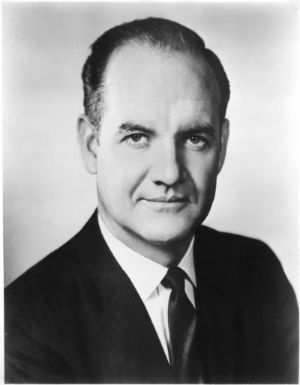

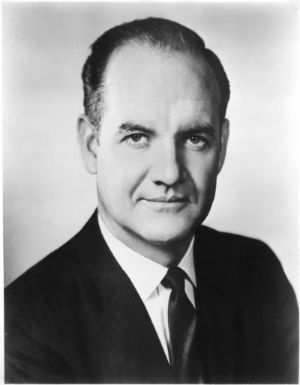

The response from Democratic Senator George McGovern of South Dakota was downright harsh. Despite the fact that the two men had campaigned together in 1960, McGovern had emerged as a vocal critic of Jackson’s policies within the Democratic Party. The freshman Senator had voted against Scoop’s request for higher defense appropriations, had voted against the Senate confirmation of Hyman Rickover as Chief of Naval Operations, and would publically challenge the decision to increase America’s military involvement in Vietnam. When McGovern heard the United Nations Speech, he became livid at what he considered to be an unforgivable slap in the face. Speaking out afterwards, McGovern declared that the speech had revealed Jackson’s

“shocking lack of knowledge of the world in which we live and of the structure of the United Nations.”

It was strong stuff; after all, openly calling the President of the United States “stupid” wasn’t something to be taken lightly. From then on, McGovern was one of the few people the usually friendly Jackson truly hated and the two men became bitter political and personal enemies. Even Democratic Senate Majority Leader Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, a close friend of Jackson’s, thought the speech was

“a great mistake” and

“very odd”.

Despite the attacks he was getting, Jackson didn’t back away from what he had said. He weathered the storm of controversy, firmly believing he had been right to criticize the role of the United Nations in American foreign policy. Jackson’s speech reflected his deep convictions about the primacy of alliances and the danger of reorienting US foreign policy in the direction of the United Nations – where countries hostile to America were given equal status and a free platform from which to bash the USA. A young White House aide named Daniel Patrick Moynihan remembered how impressed he was by the President’s performance:

“He was as solid as a rock and you know, he was right. Absolutely right. The UN wasn’t really all that helpful. It was just a place where the Soviets and the Chinese could go to undermine our values and our interests. I thought it was one of the best speeches he ever made, if not the best.”

The day after the speech, House conservatives from both political parties moved to scuttle the bonds debate. With the President having articulated his position on the UN, conservatives felt encouraged not to spend any more time talking about giving taxpayer money to an organization they weren’t crazy about either.

“Why should we give our money,” asked a first-term Republican Representative from Kansas named Bob Dole,

“To an organization that treats us like we’re the enemy?”

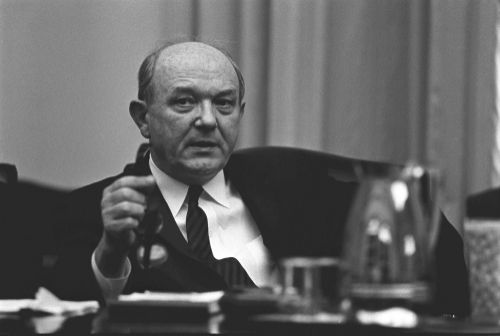

(George McGovern, circa 1961)

(George McGovern, circa 1961)

The House of Representatives, controlling the power of the purse strings, declined to buy the bonds in the end. Although it wasn’t a blow to the United Nations in the long run, the international organization was put on notice about where they fit into Jackson’s foreign policy. Pro-UN liberals blamed Jackson for the failure of the United States to fulfill what they considered to be her obligation to financially support the United Nations. The United Nations Speech itself became a turning point in Jackson’s Presidency. Although Scoop was no stranger to criticism from the Far Left fringe over his being a Cold Warrior, that criticism began to move into mainstream liberalism after March 20th, 1962. For the rest of his Presidency, Scoop Jackson – a liberal in the New Deal tradition who still worshipped Franklin D. Roosevelt – found himself being increasingly attacked by McGovern and other liberals for refusing to appease the Soviets and the Chinese in the name of easing Cold War tensions. Jackson found their idea of seeking rapprochement dangerous because it meant relying on the good will of aggressive dictatorial regimes.

“We have been down this road before,” Scoop would remind people,

“With Munich [in 1938]. People thought that if they gave Hitler what he wanted [the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia that was occupied mainly by German-speaking people] and he promised not to make any more demands, then they could continue to enjoy having peace. They thought Hitler’s word would be enough – that they wouldn’t need to stand up to him. Of course, all they managed to accomplish at Munich was to hasten the coming of war. They confirmed for Hitler that they were weak and that he had nothing to fear from them. It is a foolish thing to give an aggressor what they want and expect them to be quiet afterwards.”

Two months after the United Nations Speech, as if to provide more fuel for the fire, “The Guns of August” appeared in bookstores across the country. Written by Barbara Tuchman, the one-volume history book explored the first month of World War One. It took readers into the decision-making process that transformed the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary by a Serbian nationalist in June 1914 into a war that consumed all of Europe and beyond. Tuchman then greatly detailed the first month of fighting, culminating in the September 1914 First Battle of the Marne which halted the German advance towards Paris and set the stage for four years of brutal trench warfare. With the outbreak of World War One approaching its’ fiftieth anniversary, “The Guns of August” became very popular with readers wanting to know more about The Great War. It spent forty-two consecutive weeks on The New York Times Best Seller List and won the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction in 1963.

One person who wasn’t a fan of the book was the President. Jackson had been a two-year-old boy when World War One erupted. After being sent a copy by the well-read Democratic National Committee Chairman John F. Kennedy, Scoop read “The Guns of August” and wasn’t impressed by it like JFK was. He disagreed with Tuchman’s central tenet that war broke out in the summer of 1914 not because of German ambitions to acquire greater influence in Europe but because nations had misinterpreted the intentions of others. Because these nations misread each other, they escalated the situation into an all-out war which destroyed those same nations and sowed the seeds for World War Two. According to Jackson, that view of why Europe went to war was WRONG!!! There was no misinterpretation about anything! Germany wanted greater power for herself and she used the assassination as an excuse to launch a war that would achieve that power. So in disagreeing with the book, Jackson was also disagreeing with those using “The Guns of August” as an analogy for understanding the Cold War. Liberals were making the argument that the United States was locked into the Cold War with the Soviet Union and China because each side was misinterpreting the other. If the United States would just sit down and work things out with the Soviet Union and China, then the risk of war by miscalculation would be reduced. Once again, Scoop viewed that reasoning as WRONG!!! The reason the United States was locked into the Cold War with the Soviet Union and China was because the Soviets and the Chinese wanted greater power for themselves. Only by meeting their ambitions with American power could the Cold War be prevented from turning hot. The Soviets and the Chinese would be less likely to provoke the Americans if they felt that it was too risky. Like the UN Speech, the sharp disagreement over “The Guns of August” itself and its implications for America’s present foreign policy became another example of the widening gap between Jackson and liberals over how to deal with the Cold War. By 1964, his differences with McGovern in particular would be irreconcilable.