1939 pt 9

A platoon of Humber armored cars from the 44th Reconnaissance Regiment/7th Armored Division aggressively probe the Italian front lines

A glorious dawn broke on the morning of 17 April, 1939; the last vestiges of the previous day’s monsoon clouds were driven before a steadily creeping sunrise cresting over the Red Sea.

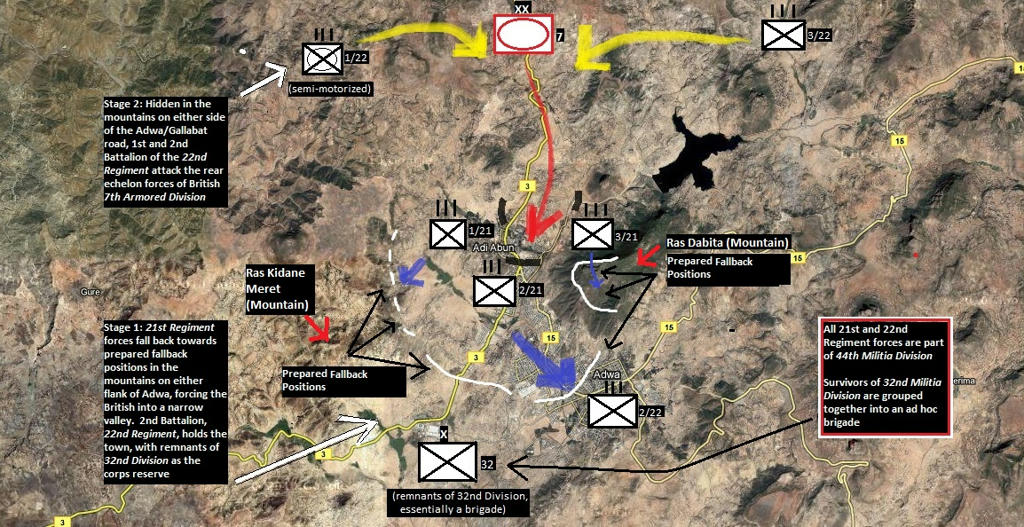

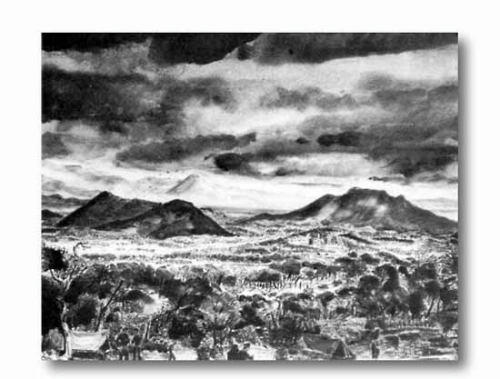

Meanwhile, 12 km north of the Adwa pass, soldiers of Montgomery’s 7th Armored Division milled about underneath a shroud of grey fog, shielded from the sunlight by towering mountains arrayed around them; the sound of bolt-action rifle actions snapping closed and machine gun breeches slamming shut pervaded the murky landscape as preparations for the attack the Italian Adwa stronghold climaxed. British tank commanders sketched tactical plans on their maps and issued final instructions to their supporting infantry units. Infantry in Bren carriers, tasked with clearing the outlying fields, began to advance in a seemingly endless column of dark silhouettes. They bobbed and bumped along, rifles slung at the shoulder, raising a cloud of dust that began to merge with the low-lying early morning mist. The sun began to crest the eastern summits, and faint sunlight glinted on the porous metalwork of fixed bow machine guns as they advanced under the protective dark outlines of tactically dispersed tank platoons. Commanders observing the advance from open hatches formed part of the menacing silhouettes of the tanks as the infantry moved forward. Wraithlike foot infantry followed behind the Bren carriers, marching uphill with heavy rucksacks but otherwise lightly armed; the dismounted infantry supported by Bren carriers would screen both sides of the main Adwa/Gallabat road, allowing Montgomery’s armor to advance without fear of flank attack.

Though his forces were resupplied and ready for battle, however, Montgomery approached Adwa cautiously, stopping his lead units frequently to allow for his second echelon forces to catch up before moving out again. The Italian defenders systematically retracted their front line with each British push; General Gariboldi had anticipated a methodical advance, hoping to draw Montgomery in. So far, the battle was proceeding exactly as anticipated by both commanders.

Soldiers of 1st Battalion of the Kings Royal Rifle Corps/7th Armored Division move into position to screen the main British armored thrust

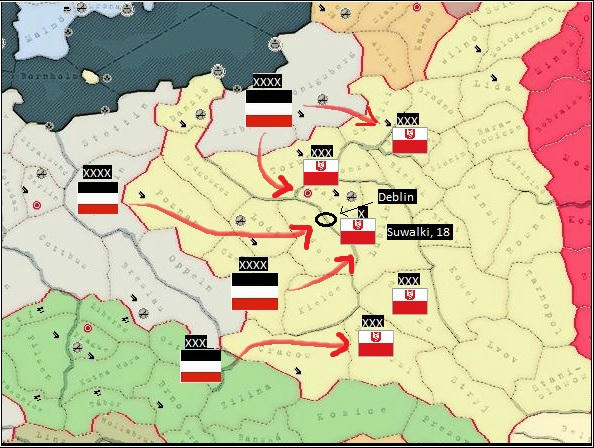

Back in continental Europe, as the German noose constricted around Warsaw, the Polish high command was starting to discover that the advantage afforded by their cavalry’s mobility became less pronounced in the increasingly constrictive plains of central Poland; as the cavalry lost their tactical maneuver room, the light horse units took increasing causalities against heavier-armed Panzer units. By dawn on the 17th of April, most Polish units that could still fight had withdrawn to the Vistula River line and Warsaw.

Dismounted Polish Soldiers from 18th Uhlan Cavalry Regiment dig in on the western bank of the Vistula River

80 km southeast of Warsaw, the 2nd Panzer Division prepared for a daylight assault on the town of Deblin, home to two major bridges spanning the Vistula River; taking this vital town would open up the eastern half of Warsaw to envelopment from the south as well as open the road to Lublin further east. If the Germans failed to take Deblin, it would force the rest of Wehrmacht to conduct a costly amphibious invasion across the Vistula in order to attack Warsaw; therefore, it was vital for the Poles to hold the town and the bridges. Opposing the crossing were the Suwalki Cavalry Brigade and the veteran 18th Uhlan Regiment, once formidable formations reduced to shadows of their former selves during two weeks of ceaseless combat.

Despite their substantial losses, Polish commanders considered themselves fortunate due to the fact that they had retreated to Deblin in good order with most of their artillery and anti-tank guns intact. Combined with the inherit defensive advantages of defending behind a major river and the fact that retreating Polish soldiers were constantly streaming to Deblin from battlefields in the west, Brigadier General Zygmunt Podhorski of the Suwalki Cavalry Brigade felt that he could hold the town for quite some time. If the Germans made a determined effort to take the town, Podhorski would detonate prepositioned explosives on both bridges to prevent the Germans from using them. Given that the German proclivity towards motorized vehicles in its so-called blitzkrieg tactical doctrine would be negated during a river crossing operation, Podhorski reasoned that the Wehrmacht would be at a distinct disadvantage in a set piece infantry battle, as the Germans were likely to be unfamiliar with the presumably antiquated concept.

On the other hand, as one of his lieutenant in the 2nd Regiment (Augustow) mentioned, the miserable condition of the stragglers, most of whom lacked their weapons, combined with the lack of any natural fallback position beyond the Vistula, forced General Podhorski to forsake his mobility and hold his position at all costs, something that a cavalry commander never wants to contemplate. To lose the bridges would mean to lose the war.

Poland on the brink of collapse

Standing at the top of a wooded hill on the eastern bank of the Vistula 2 km south of Deblin, General Podhorski had just lowered his binoculars when he heard the unmistakable whine of incoming artillery off to his northwest. Reflexively bringing the binoculars back up to his face, he scanned north towards the center of town and observed a solitary smoke plume rising from the busy riverside market in Deblin. Already he could hear the distant sound of screams amidst the blaring of klaxons; though clear skies prevailed and a pleasant Spring wind blew through the trees around him, Podhorski knew that 2nd Panzer Division’s pursuit would be remorseless. Despite the packed mass of people streaming eastward across the two spans, he needed to destroy the bridges at once, lest the Germans somehow wrest control of them. The refugees and stragglers would have to fend for themselves on the west bank.

The Polish general removed his helmet and ran his palm along the length of his freshly-shaven scalp; he had no delusions about the morality of his decision, and he knew full well that he was sacrificing many of his fellow countrymen and soldiers to the rampaging Wehrmacht in the name of military expediency. Nevertheless, he had no choice; if it meant that one group had to be sacrificed to save another, then the bridges must be destroyed. Mounting a nearby horse, Podhorski trotted deliberately down the hill towards Deblin, all the while contemplating the ethical repercussions of his fateful decision.

Advance elements of 2nd Panzer Division maneuver through Polish hamlets on the outskirts of Deblin

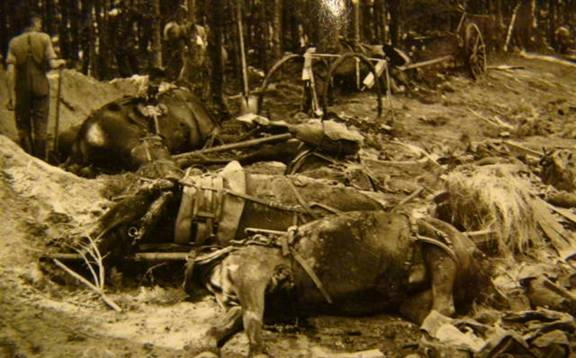

On the other side of the river, soldiers of the 3rd SS Division Totenkopf on the right flank of the 2nd Panzer Division were the first Germans to reach the environs of Deblin. Over the past eleven days, the soldiers of Totenkopf had driven along winding dusty roads, intermittently passing groups of enemy prisoners passing to the west and the occasional pile of discarded Polish military equipment but seeing little in the way of actual combat. Traveling through a village already cleared by elements of 2nd Panzer, the young Totenkopf soldiers were greeted by the first dead of the Polish campaign, a smashed Slavic skull atop a torn uniform and bare abdomen slit by shell splinters along the side of the road. The bodies of several horses lay on either side of the unfortunate soldier, all apparently killed by the same artillery strike.

Polish cavalry column ravaged by German artillery

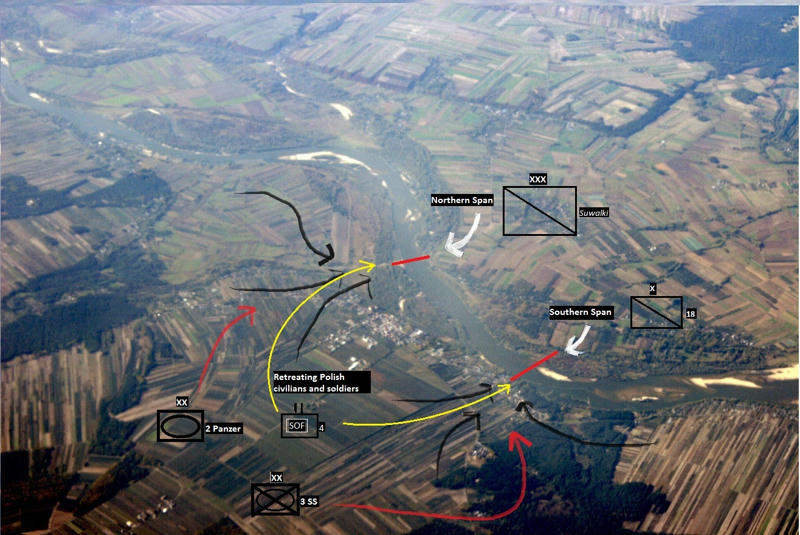

Further east, from vantage points on hills west of Deblin, officers of 2nd Panzer Division could tell that the Poles were beginning to fortify the eastern side of the city in earnest. The implications were not lost on General Heinz Guderian, commander of the 2nd Panzer; the city must be taken, and quickly, in order to support the momentum of the main thrusts towards Warsaw. Riding ahead with his vanguard, Guderian had little available firepower to storm the bridges immediately, as most of his division was still strung out along the meandering Polish roads behind him. His only chance to capture the bridges before the Poles destroyed them would be to attempt a brazen coup de main; seeing no other option, Guderian sent in the 4th Company of the ‘Ebbinghaus’ Brandenburger Battalion, along with other ad hoc platoons from his nearby infantry and panzer companies, to infiltrate and occupy the bridges in a daring mid-day assault.

Brandenburger units were Special Forces formations, usually recruited from expatriate and native-speaking refugees in areas that were deemed potential combat zones; these units were intended to operate and raid behind enemy lines, preventing demolition of key structures while also sowing confusion and havoc in enemy supply lines. Overwhelmingly concerned with blending into their environment, Brandenburgers operated in small platoons or companies to minimize their observation to the enemy. Though they were subordinated to the German Military Intelligence Directorate, or Abwehr, Admiral Canaris assigned Brandenburger companies to individual division commanders during combat; as such Guderian had direct control over the 4th Company, and they usually traveled with him in the divisional vanguard so as to quickly react to opportunities such as bridge capture. By 1400 hours on 17 April, Captain Joachim Kredel and his Brandenburgers were advancing on the Deblin bridges in captured Polish trucks, wearing captured Polish uniforms over their own German uniforms; once surprise was lost and combat was initiated, the Brandenburgers would shed their outer uniform in order to prevent friendly fire.

Guderian’s plan hinged on the Brandenburgers securing the Deblin bridges

Kredel split his company into two raiding groups, one for each of the bridges; each group raced forward at maximum speed in their captured trucks in an attempt to appear as Polish soldiers frantically retreating from the German onslaught. The quickness with which they drove into checkpoints gave the Polish guards less time to notice things out of the ordinary, such as slight deviations from passwords, subtle inaccuracies with forged papers, and presumably faulty accents. The entire operation hinged on boldness and surprise; lightly armed, the Brandenburgers did not have the firepower to last long in a fight in the case that they were discovered. Guderian would personally lead armor from 2nd Panzer and 3rd SS Totenkopf fifteen minutes after the Brandenburgers departed, adding their weight to the fight after surprise had been lost.

Northern span of the bridges at Deblin

The first Brandenburger group approached the northern span, making its way passed several checkpoints where the Brandenburgers were hurriedly waved through amidst the growing crush of refugees and soldiers. The lone artillery strike from earlier in the afternoon had spooked many of the Poles moving towards Deblin, and an atmosphere of subdued panic hung thickly in the air. Motorization has its privileges, however, and despite the throngs of Poles crowding the roads, the Germans were able to make good progress towards the bridge via liberal use of their horns to force the milling crowds to disperse off of the road. The four trucks made it to the last checkpoint at the bridge at 1408 hours; despite a cursory check by a Polish cavalry sergeant, the trucks were waved past after about fifteen seconds and a half-hearted glance at Kredel’s fictitious identification papers.

As they made their way to the bridge proper, Kredel noticed Polish armored cars on both ends of the bridge; these could possibly present a formidable problem for the Germans, though the bridge was crowded with both civilians and soldiers. Kredel reasoned that it was unlikely that the Polish armored cars would fire into a mixed crowd and decided to proceed.

As the trucks slowed to a crawl midway across the bridge, Brandenburgers began dropping off and moving towards the sides, searching for demolition charges and wires. Many of the Brandenburgers carried bolt cutters and long coils of rope; it quickly became evident to Polish soldiers inside the armored cars what was happening, but they held their fire for fear of hitting their own men and civilians. As the Poles moved to secure better firing positions, Kredel himself deftly descended from the bridge superstructure and began to cut suspected detonation cables while others prepared defenses against the inevitable Polish counterattack.

At 1412 hours, a sullen General Podhorski was just approaching the eastern checkpoint for the northern bridge at Deblin when he heard sporadic rifle fire off in the distance in front of him. He carried in his right hand the signed order directing the town commandant to blow up the bridges, and the weight of his decision was causing him severe distress. As the rifle fire intensified and the sound of grenade detonations followed, Podhorski spurred his horse into a rapid trot; a feeling of utter despair suddenly cascaded over him. He looked at the bridge some 300 yards in front of him but could not make out what was happening—were deserters being summarily executed? Were soldiers firing at German aircraft? The possibility of a German coup du main did not occur to him, but something in his gut told him that something was very wrong.

Meanwhile, a kilometer to the south, the second group of Brandenburgers were approaching the southern span over the Vistula. More motor traffic was attempting to cross the southern bridge than the northern one, and as such the Brandenburgers were waiting in line to approach the final checkpoint. It was 1413 hours, and already the commotion from the northern bridge was wafting south to the Polish sentries, heightening their sense of danger. The commander of the southern force, Captain Helmut Braun, decided that it was now or never; at his signal, several of his men jumped out of the back of the lead truck and, with fixed bayonets, rushed towards the Polish checkpoint guards while screaming in Polish that the Germans were going to kill them all. It took a few seconds for the sentries to notice that the onrushing soldiers were bearing down on them with fixed bayonets, which was all the time it took for the Brandenburgers to swiftly close with and gut both guards in one seamless movement before moving on to the bridge itself. At that moment, the three trucks that comprised Braun’s command swung out of the vehicle line and stormed the bridge, bypassing the stopped refugee traffic and crashing through the crossbar.

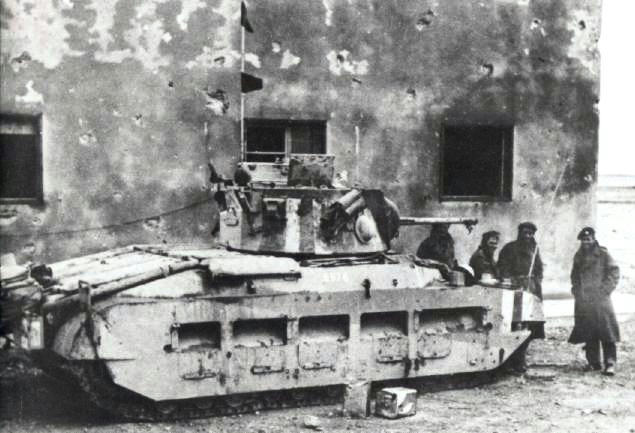

As gunfire begin to reverberate around both bridges, followed by eerie flashes and the thump of hand grenades, the lead tanks from 2nd Panzer began to arrive. They had driven up as close as they dared in the moments prior to 1415 hours, and at precisely quarter past two o’clock they had streamed into the refugee columns from the woods to the south, erupting onto the flat riverside plain south of Deblin with guns blazing, scattering soldiers and civilians alike.

German armored cars from 3rd SS charge into the fray

Despite the incoming fire, Captain Braun on the southern bridge gritted his teeth and urged his driver on. Behind him, the sound of whining engines and clanking gears indicated that the other two trucks were following closely behind. A crack followed by the iridescent red-hot slug of an anti-tank projectile spat out from the far Polish bank and slammed into his truck, passing straight through, ejecting sparks and splinters of superheated metal. The truck trundled to a halt, out of control; inside the cab, Braun’s driver had utterly disintegrated, the splattered remnants of his body lying in sloppy chunks on the floorboard and staining the seat behind him. Braun was knocked unconscious from the concussive force of the blast; as the disabled truck slowly coasted into the bridge sidewall, his limp body fell from the blown-open side door onto the deck of the bridge below. His men in the following trucks quickly dismounted and began to fervently search for cables and explosives amidst Polish fire from the opposite bank.

A murderous fire jetted out from houses alongside the Polish side of the riverbank. German panzers and infantry were, however, already making their way onto both bridge spans. The Brandenburgers already on the bridge were pinned down; worse, few could tell whether they were friend of foe, and the tanks following often shot at their own men in the chaos. Despite the intense fire from all angle, the northern group of Brandenburgers succeeded in severing most of the wires leading to the prepositioned explosives.

A German panzer kampfgruppe powers forward to rescue the exposed Brandenburgers

Back at the north bridge, motorized infantry from 3rd SS Totenkopf accompanied by armored cars lunged forward to assist the stranded Brandenburgers from Captain Kredel’s northern group. Soon the German forces were engaged in intense fighting with Polish infantry attempting to scale the river embankment and place grenades on tank tracks to immobilize them. Dueling with anti-tank guns began up and down the streets as additional Panzers and German infantry crossed the bridge and began to penetrate the houses on the eastern bank.

Fighting continued throughout the day and columns of smoke spiraled above Deblin as desperately mounted Polish counterattacks vainly attempted to wrest control of the bridges back. Air raids conducted by low-flying Polish bombers in a last ditch effort to destroy the bridges were also unsuccessful. Polish soldiers were constantly plucked from the bridge superstructure later in the day, the fanatical defenders still attempting to reignite demolition fuses. Tanks from the 2nd Panzer division and 3rd SS Division destroyed over 30 Polish armored cars, an equal number of artillery pieces, and three batteries of anti-tank guns during the battles around the bridge entry points.

German self-propelled guns support the infantry assault into Deblin on the eastern bank of the Vistula

By nightfall, Polish General Podhorski realized that his position at Deblin had become untenable. Despite throwing all of his reserves into battle, German forces continued to spill over onto the eastern bank of the Vistula via the two bridges at Deblin, and his soldiers were powerless to resist any longer. Many Polish units retreated in the encroaching darkness; those that remained fighting were systematically annihilated by German groups of stormtroopers and armored fighting vehicles.

Over the next few days, Podhorski attempted to rally survivors into makeshift battlegroups and breakout north towards Warsaw. Unfortunately, powerful German panzer thrusts outpaced the retreating cavalry units and prevented them from linking up with the final defensive bastion in the capital. Surrounded, starving, and unarmed, Podhorski surrendered his Suwalki Cavalry Brigade and the remnants of the 18th Uhlan Regiment to German General Guderian on Hitler’s birthday, 20 April. On the same day, Polish resistance in Warsaw collapsed after attacks from three German army groups that had surrounded the city, in particular armored division attacking from the south.

The German Führer celebrates his birthday with a victory over Poland

By 21 April, many of the comparably slower German infantry armies had reach Warsaw, freeing up the spearhead motorized and panzer divisions for use on the western front against France. As these armored units loaded on trains for transport west, Italian Foreign Minister Count Ciano arrived in Berlin at the head of a delegation to present a birthday gift to the German chancellor. Nestled inside an blank envelope was a road map of Northern Italy with several road and rail lines leading from Munich to Turin marked in red; Hitler looked up from the map, his brow furrowed in a contorted expression of perplexing confusion. Ciano explained to the Führer that Mussolini had graciously offered the use of his country’s transportation network to the victors of the Polish campaign; by attacking France from the Italian border, the Axis had an opportunity to end the costly stalemate in the Ruhr Valley and knock the France out of the war.

Finally realizing the gravity of Mussolini’s offer, Hitler suddenly arched backwards in howling fit of gleeful laughter. Leaning back forward, he clapped his hands together six times in rapid succession while grinning in a manner that could only be described as ‘orangutan-like’ ; Ciano could see that the Führer was pleased. As he watched the German leader begin to merrily prance around the room in a stilted yet mesmerizing dance of satisfaction, he could see that the long nights of the previous 3 weeks of war had taken their toll on the former Austrian corporal. Threads of grey were visible in the dictator’s distinctive moustache, and the skin of his cheeks seemed sunken, almost concave. Of course, the fact the Adolf had forgotten to put on pants this morning spoke volumes on the Führer’s debilitating fatigue, but Ciano decided that he would not be the first one to point that out.

Hitler’s odd prancing fit persisted for another minute, and Ciano began to feel uncomfortably nauseous, the same feeling one might get from watching female nudists play a game of tennis, of after eating a meal from an animal that was later discovered to have Down’s Syndrome. A spasm of queasiness struck Ciano; politely covering his mouth with a white handkerchief and turning away, he spied the Führer’s birthday cake. Like most of Hitler’s meals, the cake appeared bland and nutritious, a sterile, monochromatic brick of egg whites, flour, and possibly a few grains of salt. A single slice had been removed from the cake. Aware of Hitler’s demanding nutritional requirements, he wondered if the lack of meat, alcohol, sugar, and tobacco in Hitler’s diet were slowly robbing the man of his sanity.

Jubilant Germans rejoice at the news of victory against the Polish aggressors

At around the same time that Count Ciano announced that he had to return to Rome ‘for an urgent conference,’ British commander Ronald "Ronnie" Tod arrived in the village of Elafonisi, leading a small troop of hand-picked soldiers of the 1st Battalion, Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders Infantry Regiment, into the town square. His small band of soldiers had been summoned by an MI6 operative from the British Secret Intelligence Service operating in western Crete; upon hearing of bodies washing up along the beach, the MI6 operative in Heraklion had investigated and discovered the bizarre fashion in which Italian sailors had been killed.

The Aegean cove and western section of the Cretan town of Elafonisi

Battalion Commander Tod, bright beady of eye, bony of cheek and jaw, scarred, toughened, broken and reknit, grisly, and gladiatorial as a hornet, knelt down besides the body of Italian captain Cattaneo inside what passed for the town’s one-room school building. Standing around him in a rough semicircle, the seven other men from his group looked on as Tod deftly scrutinized the fallen Italian captain. Though silent, it was apparent to all present that the commander was thinking intently. After a few moments, Tod shuffled over to the back wall and inspected the bodies of several other Italian sailors; upon closer inspection, they were an ethnic mix of native Italian officers and what appeared to be Albanian midshipmen, judging by their appearance, names, and rank chevrons on the uniforms. Curiously, all of the Balkan sailors seemed to possess small-caliber bullet holes in their uniforms, while the cause of death for the Latin officers seemed to be drowning.

Without rising, Tod pointed to the town doctor, who also doubled as the local butcher, and asked him to bring over the bullets that had been removed from the bodies. The extracted ammunition rounds clanked around in a stainless steel pan with each step as the doctor/butcher brought them over from a nearby table. The doctor’s freshly bloodstained white apron stood in stark contrast to the bloated and decomposing green-tinted corpses lying in thin spruce caskets before him. Grasping the pan from the doctor’s outstretched hand, Tod examined each of the bullets in turn, squeezing them between his fingers and examining the damage to each casing.

After a few more moments of silence, one of Tod’s soldiers kneeled down on the dirt floor next to his commander; the soldier, Doctor Maynard ‘Mantis’ Toboggan, confirmed the local doctor’s assessment. The Albanian sailors had been shot to death before they had drowned.

The faint sound of a coastal breeze pushed in by the distant rolling surf inundated the small room. Tod heard his men shuffling their feet back and forth behind him; he could feel that they wanted to know why their unit had been brought to a remote town in western Crete to see a long-dead Italian captain. Commander Tod finally rose up and tuned to face the group; in the diffuse light of the squat building, his piercing aquamarine eyes seemed particularly menacing. Without warning, a sardonic grin stretched upwards from his typically somber scowl, revealing to his men that their long trip to Crete had not simply been a fool’s errand.

“What we have here boys” Tod declared to everyone in the room, “is a mutiny.”

British commandos in Elafonisi uncover shocking evidence of mutiny

Last edited: