A Most Unlikely Outcome - An Italian AAR

- Thread starter Smut Peddler

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Brilliant update.

We'll soon see if Campioni has taken the right decision.

Thanks!

You're about to find out; update in about 10 minutes.

This is a stunning AAR.

Cheers,

Sword

Appreciate it; eventually, if you wait around long enough, it will actually include some HOI screenshots too!

Good job knocking out the British carrier.

No doubt--should even up the odds some.

Great battle details!

Thanks! Writing this things is about the only thing that keeps me coming to work these days

By the way, does anyone know if its possible to change the name of an AAR/Thread after its been begun? I called this 'Most Unlikely Outcome' because i literally had not thought of a title by the end of writing the first section. I don't want to go screwing around and rename the file or something and lost everything, so i figured i'd ask you all first.

Also, any idea on a better title? I'd be willing to change it to just about anything...

In order to change the title, I think you should PM a Mod.

My proposal for a new title: Fratelli d'Italiaar !

My proposal for a new title: Fratelli d'Italiaar !

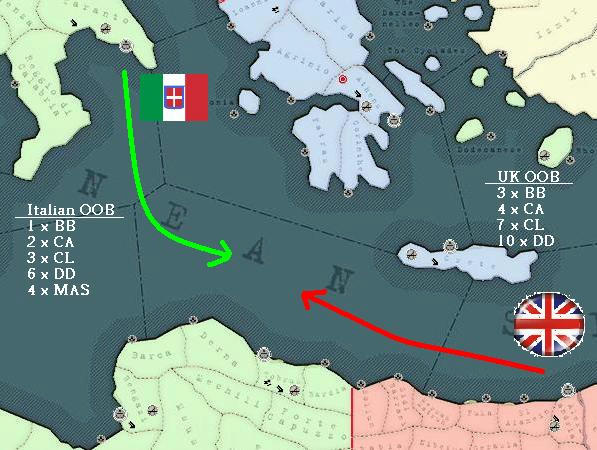

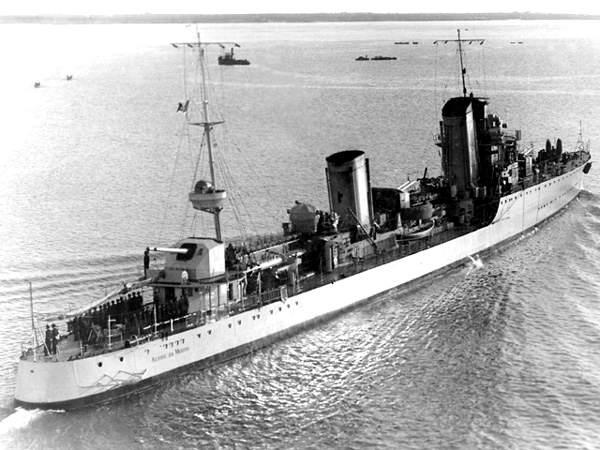

The Italian Folgore-Class Destroyer RM Fulmine scouts ahead of the 9a Squadra with the Cretan coast rising behind

Absentmindedly fixated by the dissipating droning of aircraft engines far above as 30a Stormo retired from the area, Campioni rued over his decisions as he stood hunched over glistening steel rail of the port quarterdeck, breathing in deep gasps of briny sea air in an attempt to calm his unexpectedly rattled nerves. Battle was minutes away, and his orders had all been issued; he squinted his eyes into the still-rising morning sun, trying to discern his outer picket destroyers from the smoking embers on the horizon that represented an incensed British fleet steaming to meet him. Like the waves dashing against the hull of his battleship, Doubt washed over Campioni, and the troubled admiral wondered whether he had made the right decision when he had ordered his overmatched 9a Squadra to attack the much larger British Mediterranean Fleet.

A tranquil sea, broken only by the wakes of the nearby ships of his small armada, radiated outward from the nearby coast of Crete (only 10 miles to the east) into a featureless azure prairie of undulating water swells to the west, north and south. With each trough that the battleship rhythmically plunged into, cascades of sea spray enveloped Campioni; the cool water clung to the admiral’s pressed uniform like early-morning dew on grass. Though his hearing was muffled by a steady 25 knot wind caused by Vittorio Veneto’s headlong charge into Aegean Sea, Campioni truly felt the ‘calm’ before the ‘storm’; a few more deep inhalations through his nostrils and a brief closure of his eyes, and the momentarily twitching he felt earlier had departed. Wiping misty seawater rivulets from his face with the back of his right hand, the admiral released his grip from the railing and re-entered the command bridge.

Disposition and Direction of the opposing fleets prior to the engagement

Bracing himself against the see-saw of the deck beneath him, Campioni carefully made his way over to the radar operator’s station to monitor the deployment of his fleet. The control panel for the Gufo (or “Owl”) radar set was mounted a room just behind the bridge; the radar emitter itself, emplaced high above the bridge, could in theory detect out to a range of 31 kilometers when functioning properly. At the moment, with the British battle line still some 40 km distant, all the radar showed was the intermittent signatures of his own ships. Satisfied that his ships were in their assigned positions, Campioni shuffled out of the dimly-lit room and returned to the main bridge, fatalistically resigned to the fact that the battle now just had to play out.

Vittorio Veneto was the first Italian ship to receive a prototype EC-3/Gufo (or “Owl”) radar set

Campioni, true to the reigning ‘Fleet-in-being’ doctrine subscribed to by most of the world’s navies, did not want to risk losing his new battleship in a protracted battle, and he kept his most valuable ships behind a wide screen of cruisers and destroyers. He suspected that the British would operate in a similar manner, cognizant of their numerous and far-flung Imperial commands and limited capacity to reinforce their Mediterranean theatre, even when considering the much larger overall size of the British Navy. Though perhaps more so for the Italians than the British, losses by either side in any coming battle would not be easily replaced, and Campioni’s battle plan rested on the rationale that both opposing fleets would operate cautiously so as not to provoke irrevocable losses. Moreover, Campioni reasoned that the British Admiralty would treat the Mediterranean as a secondary theatre in the overall war; their Atlantic convoys would, in all likelihood, require the greatest concentration of British ships to combat the inevitably onslaught of the German U-Boats, thus further limiting the British captain’s aggressiveness.

Campioni’s Flagship steams south as Crete’s rugged coast rises in the background

Unbeknownst to Campioni, however, were several factors working against him, not the least of which revolved around the Gufo radar set that he had placed far too much trust into. The fragile electronics of the device had been battered by the headlong charge into the eastern Mediterranean, and despite the relatively calm seas, the crashing concussions of flank speed travel led to many of the electrical leads connecting the cathode to the heater inside the cavity magnetron breaking free, causing intermittent faults inside the device. Given the radar operator’s relative unfamiliarity with the new device to begin with, the scattered and variable contacts registered on the radar screen changed position frequently and seemingly without cause. Compounding matters, the nearby coastline of Crete itself, and its many small islands as well, produced false radar echoes that occasionally give the impression of many more ships closing from due east.

In addition to misplaced faith in untested technology, Campioni also had another issue of a less-technical nature to deal with. Though they constituted a small minority overall, many ethnic Albanians served in the Regia Marina, a consequence of Albania’s close ties with Italy during the post-depression 1930’s in which Italy subsidized many Albanian state monopolies in exchange for increased influence in Albanian affairs (including the installation of Italian advisors in the Albanian military and police forces). Many Italians sympathized with the Albanians over the now infamous Tirana Incident or Alba di Incubo (‘Nightmare Dawn’), referring to the massive and unnecessary Italian bombardment of Tirana four days before. Living under a king of their own, many other Italians and Albanians alike were upset over the death of King Zog’s son and heir, Prince Leka, who had been killed on the day of his birth after an Italian cruiser shell had destroyed his nursery room in Zog’s royal palace. Altogether, these events helped to foster a covert anger towards the upper echelons of the Supermarina; in some isolated cases, incensed native Albanian sailors plotted subversion and sabotage.

RM Pola

Their collective anger found an outlet on the heavy cruiser RM Pola, where several native-Albanian ordinance loaders in the forward gun turrets were fuming over their navy’s conduct during the bombardment and lamenting their own participation in it. Most of these men were uneducated peasants from rural mountain villages; all subscribed to archaic Kanuni traditions concerning blood feuds for perceived insults to honor (similar to the Italian practice of vendetta) and felt that they had no choice but obtain their own satisfaction. Meeting in small groups and speaking in low voices, the group of around 20 men made a pact to reduce overall ship efficiency by deliberately increasing the time it took them to reload shells between salvos. Though this kind of non-violent protest could conceivably be interpreted as mutiny, especially during a combat situation, but the sympathizers felt that a ‘refusal to participate’ of sorts alleviated their conscious from the overbearing guilt of being complicit in what essentially amounted to the mass murder of their fellow Albanians. Most saw no differentiation between doing their job poorly and other acts of mild resistance, such as protests or boycotts, and to a man they all wanted to do something to express their anger, even if their plan wasn’t thought through to its logical conclusion. Despite their plotting and scheming, none seriously expected lethal reprisals from their officers for their actions. Throughout the fleet there were other groups, still loosely formed and lacking in leadership of any kind, and as such refrained from action in the coming battle due to fear of reprisal or fear of death in the coming battle, though many sailors began to contemplate how deep their convictions of duty to Italy were, and where their true loyalty lied.

The fleets gradually closed the distance between them in the rising April sun. Given the unreliability of the Italian radar and the loss of British radar from the Illustrious and Fury, the naval battle began like countless conflicts of the past, with ranging shots being fired by the first ship to spot another visually. Outlying destroyers were expected to make the first contact with the enemy, as all of the battleship-based search planes had been expended by both sides during the morning’s air combat. The hard charging British held the edge here, as a few of their destroyers possessed short-range radar, thus giving them the edge over their Italian counterparts. HMS Jervis was the first ship in either fleet to develop an accurate firing solution, and at 10:45 it commenced gunfire upon the Italian destroyer RM Fulmine. Shortly thereafter, with Fulmine’s position plotted and relayed to the new British flagship HMS Warspite, several additional shells were slung into the air.

HMS Warspite fires an opening salvo towards the 9a Squadra

Almost at once, the sea on all sides of RM Fulmine began to boil with multiple shell impacts; nearby underwater explosions flung massive columns of seawater up in towering plumes, covering the destroyer in sheet upon sheet of water that reduced visibility to zero. Changing course erratically and unsure where all of the shells were coming from, Fulmine’s captain rang for flank speed and hoped that his 38 knot top speed would allow the ship to escape the British onslaught.

Aided by radar, HMS Jervis continued to shadow the Fulmine from just over a mile away, continuing to fire downrange towards the target even while its prey commenced evasive maneuvers towards the west. Jervis also reported back to the Warspite on the accuracy of its sister ships for a time, until its radar suddenly painted 2 new targets bearing down from the north and less than 2 miles distant. Masked from visual observations by the sea spray caused by the nearby battleship shell explosions, HMS Jervis’s rapid pursuit of Fulmine led to itself becoming the prey for the pair of heavy-120 mm guns borne by the Italian destroyers RM Luca Tirago and RM Nicoloso da Recco.

RM Luca Tirago (foreground) and Nicoloso da Recco (top left) come to the rescue of RM Flumine

Destroyers of the Italian Navigatori Class were some of the largest afloat in the world, their large-bore cannon primarily intended to defeat other destroyers. As Tirago and Recco charged in from the north at their flank speed of 38 knots, each opened up with their two forward batteries of twin 50 caliber guns and tried to bracket the Jervis with concentrated and sustained fire. Traveling due west during its pursuit of Fulmine, Jervis had unwittingly presented Tirago and Recco with an inviting flank target, and the Italians surged southwards at maximum speed, constantly fine-tuning their collective fire with each impact plume near the British destroyer. Within a minute, rangefinders on the northern Italian destroyers noticed that the shell splashes were within 30 yards of their target, and though the Jervis had vectored hard to port to present a smaller-profile target and escape the Italian pursuit, it was too late for the impetuous British ship as its range had been calculated.

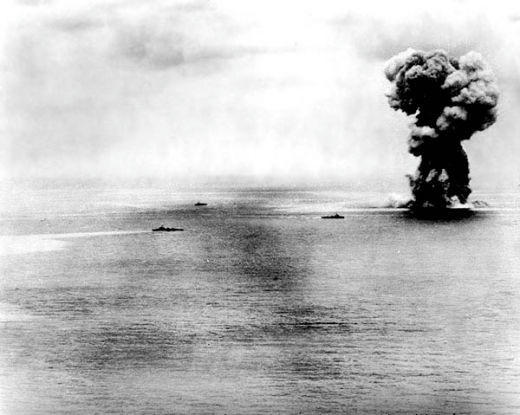

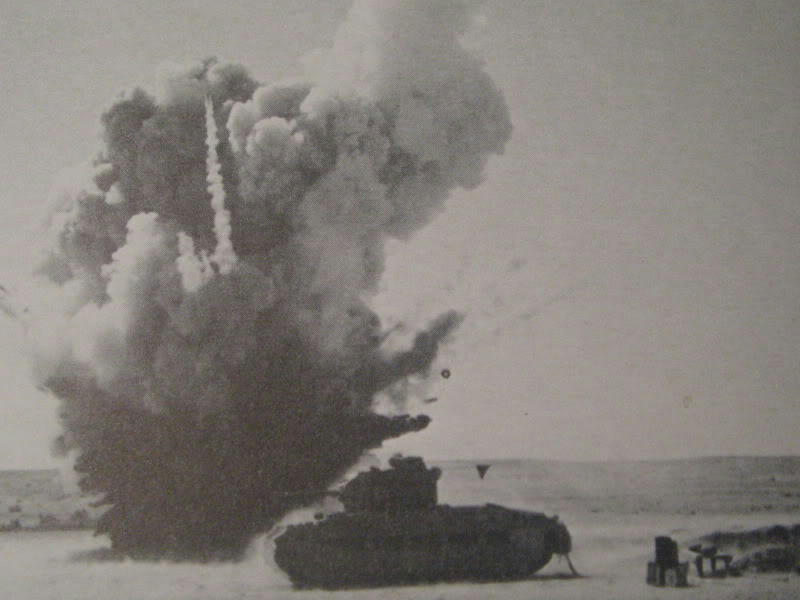

A well-aimed shell from Tirago plunged downwards into the Jervis’s superstructure, detonating with a colossal explosion that flung most of the mainmast into the air and tore open a hole large enough to expose the boilers. The fireball from the exploding fuel stores skyrocketed upwards like a beacon, and many ships in both fleets noted the location of the flames or the smoke that it produced and began to converge. RM Fulmine, finally noting the explosion behind her during a brief respite between salvos from Barham and Warspite, made a high-speed 180 degree turn to the east and made to add her firepower to the already stricken British destroyer. The rapid course change also had the effect of slowing the British battleship fire considerably, as their gun turrets could not rotate fast enough to keep pace with the Fulmine’s speed. Concurrently, Tirago and Recco slowed to one quarter speed and proceeded to rake the hapless Jervis with direct line-of-site fire. Within one minute, Jervis was hit by seven more shells from Fulmine, Tirago, and Recco; with fires raging along the length of the ship and dazed sailors jumping overboard in all directions, the trio of Italian destroyers decided that enough was enough and accelerated away towards the east. Aware of the proximity of their sailors to the Italian ships, the British battleships held their fire.

Perhaps elated from their first victory, and perhaps partially blinded by the enormous clouds of smoke belching from the wreck of Jervis, the trio of Italian destroyers unwittingly ran headlong into the scopes of British gunners aboard the light cruisers HMS Ajax and HMS Orion, who had steamed due north and were just over one mile to the east of HMS Jervis.

Light Cruisers HMS Ajax (left) and HMS Orion (right) deliver crushing cannonades towards the oncoming Italian destroyers

Broadsides from cruisers (like HMS Ajax)are nothing like broadsides from destroyers (like HMS Jervis); the three Italian ships were speeding directly into the teeth of the British cruiser’s main armament, with sixteen total 6” guns swiveled to the west to meet the nimble incoming Italian destroyers. Plunging headlong into the kill zone of modern ‘ships of the line,’ the Italians had only seconds to react. With inbound shells already screaming into their midst, all three captains independently made the decision to launch a pair of torpedoes each before breaking off and fleeing the area.

As shells rained in amongst the destroyers, sailors onboard the Tirago and Recco managed to arm and launch their forward torpedoes and break hard to port, their own rear turrets firing furiously and more for the sake of distraction than effect as they pressed northwards. RM Fulmine¸ lagging a quarter mile behind the parallel duo of Tirago and Recco, prepared to make an emergency turn 90 degrees to the south following the launch of its ordinance, in effect breaking up the large Italian target but placing Fulmine at increased risk of encountering additional British ships charging up from the south. The British cruisers, expecting their quarry to split, deftly adjusted their aim and concentrated their fire towards the northern group; the Tirago and Recco continued their port turn and eventually settled on a due north course that, it was hoped, would take them out from under the British guns. Unfortunately for the Italians, their hastily computed firing solution resulted in torpedoes that traveled along a trajectory that merely passed through the wakes of the hard charging British cruisers; instead of masking their escape with torpedo impacts, or perhaps forcing the British to evade them, the Italian Navigatori destroyers were now prone targets well within gun range of the British, even more so due to the inevitable loss of velocity caused by their 90 degree turn north.

Recco took the first hit, a 6” shell that pulverized the rear quarter just above the rudder. Control surfaces smashed, the wayward destroyer had no way to control its direction and veered haphazardly from the left to the right at indiscernible intervals, which would have proven to be a effective evasive maneuver had the drive screws not been destroyed in the same strike. As Recco drifted ever slower, several more shells found the mark in quick succession, snapping the keels in two and promptly sending the ship to the bottom.

Destroyer Nicoloso da Recco falls victim to fire from HMS Orion

Nearly lifted from the water during the nearby explosion of the Recco, Tirago nevertheless managed to stay ahead of the British cruisers’ curtain of fire, careening away on the crests of waves formed by the explosions behind her while simultaneously employing deft course changes to keep the gunners on Ajax and from establish a proper range and bearing. Tirago’s course took her north-northwest, a tack that would force her to remain in British gun range for a longer period of time, but that would also minimize her speed loss while also bringing her towards the safety of the bigger Italian ships of 9a Squadra the quickest.

Meanwhile, RM Fulmine had finally launched its pair of torpedoes and was conducting its own hard 90 degree turn south and away from the northward British light cruisers. Though briefly engaged by the Ajax’s rear turret, this harassing fire abruptly ended when both of Fulmine’s torpedoes struck Ajax’s port side amidship; though one torpedo failed to detonate, the other gutted Ajax’s midsection in a tremendous horizontal blast and temporarily cut power to the aft quarter of the ship, effectively silencing the twin cannon engaging Fulmine and allowing her to escape southwards.

While Ajax lied struggled to restore electrical power to her engines and rear weapon systems (including her Type 279 radar), HMS Orion continued to pursue Tirago in hopes of delivering a lucky shot that might slow her down. Her captain knew that the main Italian capital ships would be nearby, but perhaps driven by the appetizing morsel of the nearby yet fleeting target seemingly in his grasp, he continued to push his luck, hoping that each shot would be the one that finally slowed Tirago down.

RM Pola charging in from the west

Twenty-five km away, Campioni had been listening to his crew’s chatter over the wireless, and had decided that he needed to personally intervene if the battle was to have a favorable outcome. Keeping his flagship Vittorio Veneto along with heavy cruiser RM Zara, light cruisers RM Abruzzi and RM Garibaldi, and 4 destroyers in the main battle line, he dispatched the nearby heavy cruiser RM Pola to aid the overmatched destroyers on his left flank. To mask this detachment from enemy observation, the Vittorio Veneto angled due east to run parallel to the suspected position of the three British battleships and began firing all nine of its main 15” cannons at long range. Though his flagship could fire 775 kg shells out to approximately 35 km, his ordinance would have greater penetrative capacity and a tighter angle of descent when fired from 25 km, which would be necessary to penetrate the thick armor of the British Queen Elizabeth Class battleships HMS Barham, Warspite, and Valiant.

Vittorio Veneto prepares to fire

The British were surprised by the volume of fire put up by Vittorio Veneto, though many of the shots fell short, the Italian flagship was firing from each gun approximately once every 45-50 seconds, and the firepower had the desired effect of forcing the British battleships into a more loosely-organized formation as the two main fleets continued to close. Gradually, minute by minute, Vittorio Veneto’s shells began to cluster closer to the British battleships.

RM Pola had meanwhile closed the distance between itself and HMS Orion. RM Fulmine had lengthened its distance from Orion to a point where the Orion had begun to circle back towards the south; unfortunately, this maneuver coincided with Pola’s arrival on the scene. Caught in mid-turn, Orion began a furious fusillade of 4” and 6” defensive gunfire, blasting away madly while trying to rotate its guns in sequence with the ship’s own turn. In turn, Pola’s forward batteries engaged the exposed starboard flank of the Orion, scoring two hit on the first salvo.

HMS Orion puts up a curtain of fire during its 180 degree turn in an attempt to dissuade RM Pola’s pursuit

Neither hit did much damage, however; one landed in a 40mm anti-aircraft emplacement, destroying the gun and officer’s wardroom behind it. Pola’s other shell detonated amid the starboard quadruple torpedo mount, creating a huge fireball that scorched the armored deck of the cruiser and killing several sailors nearby but doing little internal or structural damage. Orion continued to steam southwards, shifting course slightly southeast to better align its rear turrets against the oncoming Italian cruiser. Besides being in a precarious tactical situation, the captain of the Orion also noticed that RM Tirago had sensed the changing balance of power in the area and had turned back south to assist the pursuit with Pola.

As the twin Italian ships doggedly pursued Orion southwards, Pola started receiving extremely long-range incoming fire from the (temporarily) disabled Ajax’s functional forwards battery about 10 km south. Despite being in an excellent position to deliver a crushing blow, however, Pola seemed reluctant to fire; citing all examples of difficulties, many of the loaders and gunner’s mates in her forward batteries complained that they simply could not reload the guns as usual. Extraordinary precautions for certain benign procedures had suddenly been enacted; other crewmembers developed ‘battle stress’ that induced ignorance and forgetfulness, sometimes bringing the wrong powder charges to the guns or, more often than not, walking around aimlessly as if unsure of their battle station. All the while, the Pola continued to close the gap, her top speed further bolstered by Orion’s sweeping 165 degree turn that had siphoned off most of her speed. Nevertheless, as the pursuit culminated into nearly point-blank combat, the captain of HMS Orion couldn’t help but notice that Pola was only firing from its secondary 4” armament batteries. Many of these shells hit the cruiser, but Orion’s thick armor brushed off most the superficial damage that they caused. During the 10 minutes of chase that saw Pola and Tirago nearly come alongside the Orion, the Pola fired precisely 2 salvos from its main forward emplacements. In contrast, Orion’s rear dual-turret fired 11 times, scoring 2 hits on Pola’s bow but only causing light damage; in support, Tirago also fired its main battery 11 times.

Though infrequent, RM Pola’s main battery possessed fearsome firepower

Pola and Tirago finally came abreast of Orion at about the same time as all three reached the motionless Ajax; close quarters combat of sorts ensued, with all four ships circling a common point while massive broadsides belched into the common kill zone between them, explosions ripping into and sometimes even through opposing ships. Fulmine took four shells from Ajax and another pair from Orion within the first minute and was soon fleeing to the east, oozing voluminous clouds of pitch-colored smoke and missing most of her main bridge. Damage would have been worse had some British armor-piercing ammunition not passed completely through the thin-hulled Fulmine before detonating. Though out of the action, Fulmine’s boilers and propulsion system were relatively undamaged, and she retreated north at almost 26 knots. Wisely noting Pola’s reluctance to fire, the captain of the Orion had previously radioed ahead to Ajax and directed that Tirago be their primary target.

The command deck of the Tirago takes a direct hit from Ajax, forcing her to retire from the battle

Below decks on the Pola, Captain Cattaneo and one of his lieutenants had their sidearms drawn and were ranging up and down the forward corridors in an attempt to find out what was going on. Visibly seething with rage and with eyes squinted to slits, Cattaneo walked into the ammunition storage room of Battery 1 and held a pistol to the head of the officer in charge of the gun crew; the ethnic Albanian made no move to run or question the act, and as Cattaneo was preparing to make an example of him, a tremendous concussive force knocked everyone in the room to the floor. For a moment, no one moved, and only the sound of water rushing past the outer hull and the rhythmic mechanical hammering of the steam power plant could be heard. Several dazed seconds followed, and slowly, as the officers and crew alike began to belatedly stand up, another blast suddenly rocked the ship, and the sound of rushing water became progressively louder. Cattaneo, incensed beyond belief and stringing Italian curses together in no discernible order, rose to his knees, using one hand pressed against the floor grating to balance his torso upright; his other hand (still holding his pistol) feverishly pulled on his hair like it was on fire. The dazed crewmen in the compartment could see his bloodshot eyes through the dim smoke permeating the compartment, and some could have sworn that they saw tears forming in his eyes. Despite the inrushing water, no one moved. It was at that point that Cattaneo started shooting.

As grim as the situation was below decks, however, things were scarcely better above. Cattaneo’s executive officer, however skilled he may have been in an ordinary battle situation, was utterly out his element. Standing in the middle of the glass-enclosed bridge, he could see both Ajax and Orion deliver increasingly-accurate fire against his ship; British secondary armament already had a good fix on their range to target and were systematically sweeping the Pola’s deck with punishing 4” cannon fire. With steadily mounting causalities, Tirago out of the action, and with Pola’s ineffective rate of fire, the XO made the decision to retreat.

Forewarned by RM Fulmine of the crippled power plant and inoperable rear turret on the Ajax, Pola’s acting captain continued straight south, a bold move that the British did not expect; delivering a fleeting yet bruising broadside as she passed alongside Orion, Pola sped south into Ajax’s blind spot at her best possible speed, taking scattered and inaccurate fire from the bewildered British cruisers, themselves fully expecting a northward retreat. Ajax could not fire at the southbound Pola, and Orion circled around to give chase to the wounded Italian cruiser. Fire from Pola’s rear turret was sustained and accurate, unlike her front turrets, but nevertheless, damage to the front quarter caused during the earlier fighting began to take a toll and slow Pola to 15 knots, and Orion’s pursuit was relentless as she returned fire on Pola’s rear quarter.

The move to the south also brought Pola in range of some of the main British battleships; Valiant and Barham opened up on the hapless Italian cruiser from a distance of 13 km, their shells joining with Orion’s own barrage, and the combination of fire from all ships coupled with Pola’s reduced speed left an inviting target. Within three minutes Pola had been hit by 14 British shells, including several close range shots from Orion that lowered her speed even more; dead in the water listing hard to port, RM Pola sank quickly thereafter.

An ignoble end to RM Pola

Though RM Fulmine was able to use the British fixation on Pola to swing around back north and to safety, there was very little else that went right for the Italians for the rest of the day. Both captains, struggling to accept their already grievous losses, adopted an unimaginative defensive posture for the rest of the battle, with the great battleships firing from extreme long range at suspected enemy concentrations. Deteriorating weather after 2:00 reduced visibility even more, preventing aerial reinforcement for the Italians and creating a situation that radar on both sides could not rectify.

Nevertheless, both fleets attempted to maneuver into favorable positions throughout the afternoon, and shell fire intensified as the squalls grew in strength. Around 3:00 HMS Warspite suffered 3 hits in rapid succession from Vittorio Veneto, which wrecked the second flag bridge and killed outright the 2nd fleet admiral of the day, among other major damage. Italy’s other heavy cruiser, the RM Zara, also received several near-misses from HMS Barham while trying to avoid semi-accurate fire from HMS Valiant, resulting in severe damage under the waterline and forcing her to withdraw. Destroyers on either side zipped around at high speed, trading shots from time to time but only serving to seriously threaten their individual fuel supplies.

The British Fleet finally breaks contact

In the gathering dusk around 5:00, both fleets began the process of covering their retreats and fishing for survivors. The British were first to depart, moving back their battleships to a rear-guard position where they could cover the rest of their faster ships before moving en masse towards Alexandria. By this time, HMS Ajax and HMS Cornwall had made field repairs to their drive systems, allowing them to keep pace with the 14 knot fleet speed that would allow them to overtake and protect the stricken HMS Illustrious within a few hours. Left behind were the hulks of destroyers HMS Fury and Jervis.

Back outside underneath the low, backlit storm clouds, a thoroughly drenched Admiral Campioni breathed in deeply while he prepared for his departure from the battle area; he had allowed sufficient time to hunt for survivors and lifeboats among the wreckage seeding the Mediterranean, and had given the order for all ships to return to Taranto at 23 knots. As his flagship slowly turned northwest, he considered how he would explain the loss of the heavy cruiser RM Pola and the destroyer Nicoloso da Recco, to say nothing about the major damage to RM Zara and RM Tirago. After a magnificent early victory, Campioni had done little to press his advantage; his early maneuvering had gone well, and his destroyers had nearly lured several British cruisers into gun range of Vittorio Veneto at one point, but in the end he had inflicted far fewer losses than he had expected. He was also still reeling from the loss of Pola; most disconcerting were the reports of Pola’s exceptional opportunity to sink HMS Orion, though in the end, little had come of it. Chalking up the failure to inaccurate marksmanship, Campioni made a mental note to increase main battery training on all of his capital ship gun crews.

Gazing into an orange westerly sunset almost completely hidden behind a low storm cloud bank, Campioni wondered how Admiral Cavagnari would react to his arrival.

Looking down towards the white-capped waves as they slapped angrily against the ship’s prow, he was struck by the answer to his own questions and muttered it aloud: “Foot to ass.”

Vittorio Veneto slows to pick up stranded survivors from RM Pola

Last edited:

This AAR is incredible! The most realistic AAR I've ever read. It really takes you there. Well done, mate.

Cheers,

Sword

Cheers,

Sword

Good follow up story.

The Tirago hit pic was actually a light carrier which already earmarked for my AAR

The Tirago hit pic was actually a light carrier which already earmarked for my AAR

In order to change the title, I think you should PM a Mod.

My proposal for a new title: Fratelli d'Italiaar !

i will definately look into this--incidently, why 'fratellli' ('siblings' ???)

Another awesome naval action update.

That Albanian plot was well thought !

Thanks! I may not be done with this angle just yet either...

This AAR is incredible! The most realistic AAR I've ever read. It really takes you there. Well done, mate.

Cheers,

Sword

I appreciate it! I'm glad you all are still following!

Good follow up story.

The Tirago hit pic was actually a light carrier which already earmarked for my AAR

haha, sorry about that! if you want, i'll flip the picture horizontally in MS Paint and it will look different from yours! It is difficult to find 'explosive' picturs of smaller ships, but with enough smoke and fire, sometimes its hard to tell what's being destroyed

Another awesome update, Smut Peddler. The final line really does say it all.

Thanks for the comments! Lamentably, no update this week on account of actually having work to do; hopefully next week will be a little slower.

i will definately look into this--incidently, why 'fratellli' ('siblings' ???)

I would say brothers rather than siblings.

And why ?

Because of

Fratelli d'Italia,

l'Italia s'è desta,

dell'elmo di Scipio

s'è cinta la testa.

Dov'è la Vittoria?

Le porga la chioma,

ché schiava di Roma

Iddio la creò.

The beautiful Italian national anthem !

haha, sorry about that! if you want, i'll flip the picture horizontally in MS Paint and it will look different from yours! It is difficult to find 'explosive' picturs of smaller ships, but with enough smoke and fire, sometimes its hard to tell what's being destroyed

No issue here! Maybe it should be me who flip the pix since you posted before me

My HDD folder is full of beaten up carrier and BBs picture from all i can find from the Net

But there are not too many of ships being caught in the process of being blown apart back in WWII, this ain't recent Iraq war where things are live on TV!

I do wonder what WWII live on television would have looked like.

Great stuff so far! Though it might be easier to engage the RN on your terms, that is, once you've grabbed Gibraltar and Suez. Then mop up for the kills!

I do wonder what WWII live on television would have looked like.

It will create a great chasm between those for the war and those against because the horrors of war is now so graphic and because they seeth at the images of the death of their countrymen.

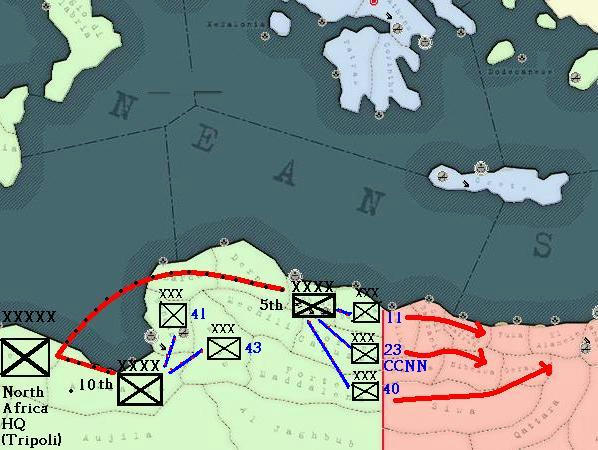

400 km to the south, Campioni’s British adversaries in North Africa were also falling back after a battle.

Lieutenant-General Archibald Wavell scarcely remembered his own name; after narrowly surviving devastatingly-accurate Italian artillery barrages three times in the past twelve hours, the newly-cycloptic Brit was literally exhausted, both from narrowly escaping death many more times than is usual during any particular day, and from personally doing the command work that his formerly-living staff officers usually completed. Already twice wounded in the face and arm by shrapnel from near-misses, Wavell struggled to hold down both sides of a map detailing the pitiful road network in the Nibeiwa area, where his HQ staff had recently retreated and were now struggling to establish communications. A nearby cook, recently pressed into service as an aide, moved to assist Wavell by holding down one corner of the tattered document, preventing the map from its natural inclination to curl into itself, as has been the norm for this particularly-obscure map for many years. The dull thump of explosions into loose sand resonated from all around as the two men attempted to determine their exact location in the expansive sea of sand where they now found themselves; given the featureless surrounding terrain and lack of any kind of landmark, it did not take them long to arrive at the conclusion that they were hopelessly lost.

Wavell’s command had been driven back over 45 km in the past eight hours. Ill prepared for defensive operations, British forces under his command had been staging for an offensive into Cyrenaica since the declaration of war on 4 April, stockpiling petrol and ammunition in forward area caches in expectation of a quick strike into the suspected weakly-manned Italian defenses. Wavell’s 7th Armored Division had been concentrated near the town of Nabia, from where it could quickly strike into Forte Capuzzo and from there either lunge behind Italian line and race for Tobruk (and thereby isolate forward Italian forces near Bardia) or advance independently of the other four British infantry divisions and move due west towards the main Italian logistical base at Benghazi. Unfortunately for Wavell and the British, uncannily-accurate and massive Italian artillery barrages on the morning of 6 April thwarted these plans; most of the supply depots had been destroyed, and the concentration of British armored and motorized forces into smaller staging areas had resulted in large losses of men and materiel. Compounding matters, the surviving British troops were without the benefit of their extensive defensive works further east; by moving up to the starting line on the border, they were without the benefit of their defensive minefields, barbed wire, pre-plotted artillery kill zones, or integrated fire bunkers. In effect, by moving into position to invade, they had become perfect targets for the waiting Italians. As a result, the Italian 5th and 10th Armies had relentlessly hammered the British concentrations with all available artillery and, after the smoke of the bombardment had risen, easily smashed through the broken British front line, pushing them back towards the east.

Wavell’s command hovel had been crafted from dried mud and was only dimly lit from a small south-facing square window; in a corner of the room, three wireless radios squawked intermittently with pleas for help from his subordinate commands. All of a sudden, the shock wave of an artillery shell impact nearby thundered through the walls of Wavell’s primitive mud shack command post; as the reverberations passed, dust and soot floated gently earthwards from the flimsy structure’s reed ceiling, obscuring some of the locations on the map with broken pieces of wood and mottled dirt. Wavell swept the bandaged stump of his left hand to brush away the gritty obstructions and, in doing so, allowed the released end of the old map to again coil into itself. Bellowing primal curses rooted in the day’s catastrophic losses mingled with his own debilitating fatigue, Wavell clumsily jabbed the nub of his hand at the map in a dragging motion in an attempt to unravel it, serving only to fold and tear the old map all the more. Sensing his despondency, the cook/aide leaned forward and stretched across the length of table in order to hold both ends of the map to the rickety table beneath it.

As Wavell looked downward and began to once again attempt to discern his position, what appeared to be a raindrop splattered down onto the map, again obscuring some locations from his view. With his one good eye, Wavell looked up through the spaces between the wood in the patchwork ceiling and observed an azure sky completely devoid of clouds. Furrowing his brow, he looked back down and saw additional droplets begin to pepper the map, each one thick and dark, like crimson ink. Instinctively, Wavell brought his good right hand up to his bandaged-wrapped forehead and immediately felt moisture permeating the field dressing. Frenzied unraveling followed, and as the cook/aide looked on, it quickly became apparent to both that the concussion from the last artillery near-miss had shattered Wavell’s glass eye in the socket. With pressure from the wound released, the jagged glass pieces began to expand and separate, and Wavell howled in pain as the shards began to puncture the sensitive flesh of his ocular cavity. Though some smaller pieces towards the front of the eye fell into Wavell’s hand, most of the remaining shards were pressed back into the socket as he reflexively brought his hand up to his head. Overwhelmed by his general’s maniacal shrieking, coupled with the ceaseless calls for assistance coming from the nearby wireless radio sets and his own frayed nerves, the cook/aide panicked and ran out the doorway and into the desert.

Meanwhile, at the Italian 23rd CCNN Corps headquarters, Lieutenant-General Giuseppi de Stephanis stood before his own map table and calmly watched his commanding officer’s decisive masterstroke unfold before him. Unlike Wavell’s flimsy hut, de Stephanis’s command center was the picture of mechanical efficiency; orders were issued calmly over the wireless in measured, efficient segments. Runners walked in and out without haste, as if entering a Milanese office building. Most importantly of all, a special radio set monitored in the next room conveyed up-to-the-minute communiqués from Badoglio’s ‘Good Source’ inside the British 8th Army, which allowed de Stephanis to expertly maneuver his forces where they could inflict maximum damage against the now-routed British.

His 2nd Division ’XXVIII Ottobre’ and 4th Division ‘Ill Gennario’ were leading the 23rd Corps drive into the British defenses south of Sollum, and by all reports the Italians were advancing ahead of schedule. Everywhere, British and Indian troops were being driven from the field after only brief fighting; there were far more desertions and surrenders than had been expected, and in general the British 8th Army seemed to be fleeing in disorder towards Egypt. A skilled and accomplished tactician, General de Stephanis nevertheless seemed almost more disappointed than pleased by the results of the massive artillery strike; he had been eager to employ his extensively-trained Camicie Nere fascist volunteers and Bersaglieri regiments in battle, and now felt somewhat cheated that Badoglio’s spy network and artillery had opened the gates for his troopers to only mop up the remnants.

De Stephanis walked over to his radio operator’s desk and briefly thumbed through some of his divisional situational reports and preliminary interrogation transcripts; most contained reports of British soldiers short on ammunition and fuel after only a few hours of battle, and the reports that didn’t instead concentrated on the utter shock wrought by the Italian preliminary artillery bombardment. A few British officers had been captured as well, and most of them had lamented on the fact that the Italians had somehow known exactly where to hit them, almost as if the Italians had been privy to the British order of battle and their deployment. More than a few lashed out about the ‘unsportsmanlike sniping’ of British leadership in the opening salvos; deliberately targeting battalion and regimental HQ’s, many British officers claimed, was no way to conduct a ‘civilized war.’

Back in Europe, the general situation still favored the Axis through the critical first week of war. German Westwall defenses had succeeded in breaking up the lethargic Allied effort to penetrate into the Aachen and Duren defensive belts, and several German counterattacks on the night of 7 April by the 1st and 15th Panzer Divisions had driven the Allies back to their start positions with significant losses to both sides. Fortunately for the Axis, most of the vehicle losses incurred during the German attack were of the soon-to-be obsolete Type 2, which would soon be replaced by the more formidable Panzer type 3 and type 4 armored fighting vehicles. Further south, French alpine troops along the Franco-Italian border had made no movements, either to attack Italy directly or to move north to support offensive operations against Germany. Though it was far too early to tell for sure, all indications were pointing to a continuation of World War One-era trench warfare tactics on the short Franco-German border.

Both the Allies and Axis were pressuring the Low Countries, though in different ways; Germany was trying to keep both Belgium and the Netherlands out of the war in order to keep their western frontline short, while for their part the Allies were trying to bring both countries into the war in order to open up the front. Though they had so far refused to entreaty either side, Count Ciano joked often to Mussolini of the perceived Belgian ‘waffling’ between isolationism and interventionism, remarking that it was a small victory every day that Belgium refrained from entering the war, in that it gave Germany time to finish off the Poles, who were only now reeling from successive German onslaughts from East Prussia and Breslau. Despite this superficial optimism, however, Mussolini and his court felt that it was only a matter of time before the ideological similarities and majority French demographic of Belgium pushed that country firmly into the Allied camp.

The Dutch were a different case altogether. Though concerned by the rise of National Socialism in Germany and the possibility of armed conflict in the future, most Dutch citizens expected that Germany would again respect Dutch neutrality, as Germany had done during World War One, and the Dutch were more than willing to respect German sovereignty in kind. Complicating matters, even in April of 1939 the Netherlands were still languishing in the throes of the great depression, and their refusal to drop the gold standard (as most other nations had done) had helped lead to a rise in Dutch national socialist parties like NSB (Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging), which boasted over 37,000 members and supported neutrality with Germany at all costs. Interestingly, the Netherlands had mimiced Italy throughout the 1930’s in many respects, particularly in regards to subordinating individual interests to national interests, endorsing embryonic corporatism, fostering strong government institutions, and placing an overriding emphasis on authortiy and order. These themes resonated alongside the popular attraction of communism, though Dutch and Italian types of socialism both retained aspects of the archaic guild system and favored direct negotiations between collectives of owners, workers, and state employees rather than top-down directives, as in socialsim; in the end, this resulted is something more palatably democratic than oligarchic communism. As a consequence, Mussolini believed that the Dutch flirtation with socialism indicated that they would not simply ally with France along ideological lines, and would be just as willing to fight against the French as they would against the Germans; the determining factor would be whoever violated Dutch soverignity first.

Il Duce retired early on the evening of 8 April. Shuffling down the marble hallway of the Palazzo Venezia with a crystal snifter of Venetian grappa deftly pressed between his thumb and index finger and buoyed by the apparent success of his armed forces during the first week of war, Mussolini eagerly looked forward to a well deserved, restful sleep.

At the same time 1,500 km away, on the extreme west coast of Crete near the town of Elafonisi, local villagers were gathering in the dusk along a secluded beach cove. A chilly Spring wind blew in from the Mediterranean, pushing several uniformed bodies in with the evening’s high tide. While strange bodies floating ashore may not have been especially surprising to the villagers, considering the previous day’s nearby naval battle, what puzzled them was the fact that many of the bodies floating limply in the undulating surf seemed to be riddled with small caliber bullet holes.

A small boy of about nine years, in the company of two younger friends, timidly approached the closest body on the beach with a small branch in hand. The body was face down in the wet sand, and the boys tried to flip the body over without actually touching it, using only the branch to make contact with the bloated corpse. After a few minutes of pushing and prodding, the branch cracked audibly and then snapped in two; villagers standing along the edge of the beach laughed softly, and the boys, now suitably embarrassed, overcame their fear and collectively heaved the body onto its back.

With darkness oozing into the cove, the boys had trouble making out any distinctive markings on the uniform and had to wait for some of the villagers to approach with lamps. As the light from the approaching torches gradually intensified, a word appeared underneath the left breast pocket.

The word was written in Italic script. The boy attempted to pronounce it: “Cattaneo.”

Lieutenant-General Archibald Wavell scarcely remembered his own name; after narrowly surviving devastatingly-accurate Italian artillery barrages three times in the past twelve hours, the newly-cycloptic Brit was literally exhausted, both from narrowly escaping death many more times than is usual during any particular day, and from personally doing the command work that his formerly-living staff officers usually completed. Already twice wounded in the face and arm by shrapnel from near-misses, Wavell struggled to hold down both sides of a map detailing the pitiful road network in the Nibeiwa area, where his HQ staff had recently retreated and were now struggling to establish communications. A nearby cook, recently pressed into service as an aide, moved to assist Wavell by holding down one corner of the tattered document, preventing the map from its natural inclination to curl into itself, as has been the norm for this particularly-obscure map for many years. The dull thump of explosions into loose sand resonated from all around as the two men attempted to determine their exact location in the expansive sea of sand where they now found themselves; given the featureless surrounding terrain and lack of any kind of landmark, it did not take them long to arrive at the conclusion that they were hopelessly lost.

Survivors of British 8th Army HQ Staff attempt to reestablish command and control

Wavell’s command had been driven back over 45 km in the past eight hours. Ill prepared for defensive operations, British forces under his command had been staging for an offensive into Cyrenaica since the declaration of war on 4 April, stockpiling petrol and ammunition in forward area caches in expectation of a quick strike into the suspected weakly-manned Italian defenses. Wavell’s 7th Armored Division had been concentrated near the town of Nabia, from where it could quickly strike into Forte Capuzzo and from there either lunge behind Italian line and race for Tobruk (and thereby isolate forward Italian forces near Bardia) or advance independently of the other four British infantry divisions and move due west towards the main Italian logistical base at Benghazi. Unfortunately for Wavell and the British, uncannily-accurate and massive Italian artillery barrages on the morning of 6 April thwarted these plans; most of the supply depots had been destroyed, and the concentration of British armored and motorized forces into smaller staging areas had resulted in large losses of men and materiel. Compounding matters, the surviving British troops were without the benefit of their extensive defensive works further east; by moving up to the starting line on the border, they were without the benefit of their defensive minefields, barbed wire, pre-plotted artillery kill zones, or integrated fire bunkers. In effect, by moving into position to invade, they had become perfect targets for the waiting Italians. As a result, the Italian 5th and 10th Armies had relentlessly hammered the British concentrations with all available artillery and, after the smoke of the bombardment had risen, easily smashed through the broken British front line, pushing them back towards the east.

Italians forces and movements, 6 April, 1939

Wavell’s command hovel had been crafted from dried mud and was only dimly lit from a small south-facing square window; in a corner of the room, three wireless radios squawked intermittently with pleas for help from his subordinate commands. All of a sudden, the shock wave of an artillery shell impact nearby thundered through the walls of Wavell’s primitive mud shack command post; as the reverberations passed, dust and soot floated gently earthwards from the flimsy structure’s reed ceiling, obscuring some of the locations on the map with broken pieces of wood and mottled dirt. Wavell swept the bandaged stump of his left hand to brush away the gritty obstructions and, in doing so, allowed the released end of the old map to again coil into itself. Bellowing primal curses rooted in the day’s catastrophic losses mingled with his own debilitating fatigue, Wavell clumsily jabbed the nub of his hand at the map in a dragging motion in an attempt to unravel it, serving only to fold and tear the old map all the more. Sensing his despondency, the cook/aide leaned forward and stretched across the length of table in order to hold both ends of the map to the rickety table beneath it.

As Wavell looked downward and began to once again attempt to discern his position, what appeared to be a raindrop splattered down onto the map, again obscuring some locations from his view. With his one good eye, Wavell looked up through the spaces between the wood in the patchwork ceiling and observed an azure sky completely devoid of clouds. Furrowing his brow, he looked back down and saw additional droplets begin to pepper the map, each one thick and dark, like crimson ink. Instinctively, Wavell brought his good right hand up to his bandaged-wrapped forehead and immediately felt moisture permeating the field dressing. Frenzied unraveling followed, and as the cook/aide looked on, it quickly became apparent to both that the concussion from the last artillery near-miss had shattered Wavell’s glass eye in the socket. With pressure from the wound released, the jagged glass pieces began to expand and separate, and Wavell howled in pain as the shards began to puncture the sensitive flesh of his ocular cavity. Though some smaller pieces towards the front of the eye fell into Wavell’s hand, most of the remaining shards were pressed back into the socket as he reflexively brought his hand up to his head. Overwhelmed by his general’s maniacal shrieking, coupled with the ceaseless calls for assistance coming from the nearby wireless radio sets and his own frayed nerves, the cook/aide panicked and ran out the doorway and into the desert.

Italian artillery explodes near Wavell’s desert command post

Meanwhile, at the Italian 23rd CCNN Corps headquarters, Lieutenant-General Giuseppi de Stephanis stood before his own map table and calmly watched his commanding officer’s decisive masterstroke unfold before him. Unlike Wavell’s flimsy hut, de Stephanis’s command center was the picture of mechanical efficiency; orders were issued calmly over the wireless in measured, efficient segments. Runners walked in and out without haste, as if entering a Milanese office building. Most importantly of all, a special radio set monitored in the next room conveyed up-to-the-minute communiqués from Badoglio’s ‘Good Source’ inside the British 8th Army, which allowed de Stephanis to expertly maneuver his forces where they could inflict maximum damage against the now-routed British.

His 2nd Division ’XXVIII Ottobre’ and 4th Division ‘Ill Gennario’ were leading the 23rd Corps drive into the British defenses south of Sollum, and by all reports the Italians were advancing ahead of schedule. Everywhere, British and Indian troops were being driven from the field after only brief fighting; there were far more desertions and surrenders than had been expected, and in general the British 8th Army seemed to be fleeing in disorder towards Egypt. A skilled and accomplished tactician, General de Stephanis nevertheless seemed almost more disappointed than pleased by the results of the massive artillery strike; he had been eager to employ his extensively-trained Camicie Nere fascist volunteers and Bersaglieri regiments in battle, and now felt somewhat cheated that Badoglio’s spy network and artillery had opened the gates for his troopers to only mop up the remnants.

Elite Italian Bersaglieri troops wait for the order to advance

De Stephanis walked over to his radio operator’s desk and briefly thumbed through some of his divisional situational reports and preliminary interrogation transcripts; most contained reports of British soldiers short on ammunition and fuel after only a few hours of battle, and the reports that didn’t instead concentrated on the utter shock wrought by the Italian preliminary artillery bombardment. A few British officers had been captured as well, and most of them had lamented on the fact that the Italians had somehow known exactly where to hit them, almost as if the Italians had been privy to the British order of battle and their deployment. More than a few lashed out about the ‘unsportsmanlike sniping’ of British leadership in the opening salvos; deliberately targeting battalion and regimental HQ’s, many British officers claimed, was no way to conduct a ‘civilized war.’

British mechanized troops retreat through the rubble of Rabia

Back in Europe, the general situation still favored the Axis through the critical first week of war. German Westwall defenses had succeeded in breaking up the lethargic Allied effort to penetrate into the Aachen and Duren defensive belts, and several German counterattacks on the night of 7 April by the 1st and 15th Panzer Divisions had driven the Allies back to their start positions with significant losses to both sides. Fortunately for the Axis, most of the vehicle losses incurred during the German attack were of the soon-to-be obsolete Type 2, which would soon be replaced by the more formidable Panzer type 3 and type 4 armored fighting vehicles. Further south, French alpine troops along the Franco-Italian border had made no movements, either to attack Italy directly or to move north to support offensive operations against Germany. Though it was far too early to tell for sure, all indications were pointing to a continuation of World War One-era trench warfare tactics on the short Franco-German border.

German panzergrenadiers from 1st Panzer Division mass for a counterattack near Bastogne

Both the Allies and Axis were pressuring the Low Countries, though in different ways; Germany was trying to keep both Belgium and the Netherlands out of the war in order to keep their western frontline short, while for their part the Allies were trying to bring both countries into the war in order to open up the front. Though they had so far refused to entreaty either side, Count Ciano joked often to Mussolini of the perceived Belgian ‘waffling’ between isolationism and interventionism, remarking that it was a small victory every day that Belgium refrained from entering the war, in that it gave Germany time to finish off the Poles, who were only now reeling from successive German onslaughts from East Prussia and Breslau. Despite this superficial optimism, however, Mussolini and his court felt that it was only a matter of time before the ideological similarities and majority French demographic of Belgium pushed that country firmly into the Allied camp.

The Dutch were a different case altogether. Though concerned by the rise of National Socialism in Germany and the possibility of armed conflict in the future, most Dutch citizens expected that Germany would again respect Dutch neutrality, as Germany had done during World War One, and the Dutch were more than willing to respect German sovereignty in kind. Complicating matters, even in April of 1939 the Netherlands were still languishing in the throes of the great depression, and their refusal to drop the gold standard (as most other nations had done) had helped lead to a rise in Dutch national socialist parties like NSB (Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging), which boasted over 37,000 members and supported neutrality with Germany at all costs. Interestingly, the Netherlands had mimiced Italy throughout the 1930’s in many respects, particularly in regards to subordinating individual interests to national interests, endorsing embryonic corporatism, fostering strong government institutions, and placing an overriding emphasis on authortiy and order. These themes resonated alongside the popular attraction of communism, though Dutch and Italian types of socialism both retained aspects of the archaic guild system and favored direct negotiations between collectives of owners, workers, and state employees rather than top-down directives, as in socialsim; in the end, this resulted is something more palatably democratic than oligarchic communism. As a consequence, Mussolini believed that the Dutch flirtation with socialism indicated that they would not simply ally with France along ideological lines, and would be just as willing to fight against the French as they would against the Germans; the determining factor would be whoever violated Dutch soverignity first.

Dutch soldiers fortify both their eastern and western borders after the Allies declare war on Germany

Il Duce retired early on the evening of 8 April. Shuffling down the marble hallway of the Palazzo Venezia with a crystal snifter of Venetian grappa deftly pressed between his thumb and index finger and buoyed by the apparent success of his armed forces during the first week of war, Mussolini eagerly looked forward to a well deserved, restful sleep.

At the same time 1,500 km away, on the extreme west coast of Crete near the town of Elafonisi, local villagers were gathering in the dusk along a secluded beach cove. A chilly Spring wind blew in from the Mediterranean, pushing several uniformed bodies in with the evening’s high tide. While strange bodies floating ashore may not have been especially surprising to the villagers, considering the previous day’s nearby naval battle, what puzzled them was the fact that many of the bodies floating limply in the undulating surf seemed to be riddled with small caliber bullet holes.

A small boy of about nine years, in the company of two younger friends, timidly approached the closest body on the beach with a small branch in hand. The body was face down in the wet sand, and the boys tried to flip the body over without actually touching it, using only the branch to make contact with the bloated corpse. After a few minutes of pushing and prodding, the branch cracked audibly and then snapped in two; villagers standing along the edge of the beach laughed softly, and the boys, now suitably embarrassed, overcame their fear and collectively heaved the body onto its back.

With darkness oozing into the cove, the boys had trouble making out any distinctive markings on the uniform and had to wait for some of the villagers to approach with lamps. As the light from the approaching torches gradually intensified, a word appeared underneath the left breast pocket.

The word was written in Italic script. The boy attempted to pronounce it: “Cattaneo.”

Crewmen from RM Pola wash up on a Cretan beach near the town of Elafonisi

Outstanding work as always !

With such an offensive, the Italian units will soon reach Alexandria.

With such an offensive, the Italian units will soon reach Alexandria.