1939 pt 4

Hybrid Italian/German MAS Torpedo Boats prowl the Adriatic in the opening hours of the war

Oblivious to the concurrent maneuvers of their Army comrades, the

Regia Marina had been ordered into action in the early hours of 5 April, 1939. Grand Admiral Domenico Cavagnari had sortied the

9a Squadra di Marina under Admiral Campioni out of Taranto, with orders to patrol the eastern approaches of the Adriatic and report on any allied expeditions from the great port of Alexandria. Similar orders were given to the

5a Squadra in Palermo (to patrol the Maltese coast) and to the

1a Squadra out of La Spezia (to counter any French movements from the port of Marseilles). All 3 squadrons consisted of light, fast ships appropriate to the mission of detection first and fighting second; all of the older battleships and heavier cruisers were kept in port, while destroyers, light cruisers, and new ships capable of 25+ knots were exclusively deployed.

Vice Admiral Inigo Campioni’s force consisted of two of the newer heavy cruisers (

RM Pola and

RM Zara), the new (32 + knot) battleship

Vittorio Veneto, three light cruisers (

RM Abruzzi ,

RM Garibaldi, and

RM Montecuccoli), six destroyers, and four MAS (or “

Motoscafo Armato Silurante”) fast torpedo boats. Air cover was provided by 2 groups of naval bombers (SM.79

Sparviero bombers) of the 9a and

30a Stormo (Wing) flying from Taranto. Campioni’s ships represented the latest in Italian technology; his light cruisers were newer, faster, fired heavier shells to a greater range, and were better armored than their British counterparts, and his new battleship had performed well during the bombardment of Albania during the previous week and possessed a prototype radar as well. But perhaps the biggest surprise in Campioni’s arsenal was his MAS torpedo boats, only recently completed by the Ansaldo shipworks in Genoa and representing the first major joint enterprise to be concluded with Italian and German collaboration since the inception of the Axis Alliance.

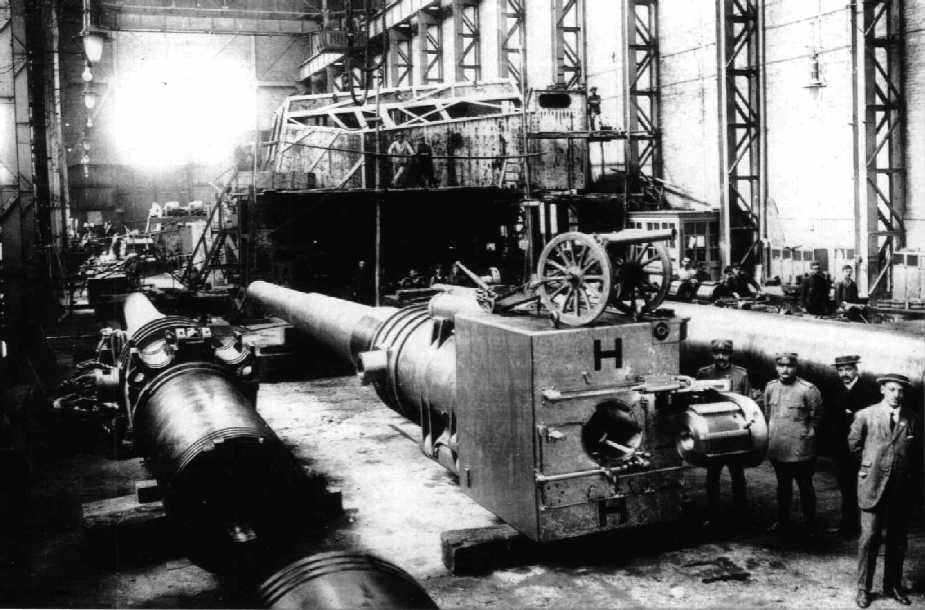

Ansaldo comprised engineering expertise with ship and armored vehicle manufacturing

With refinements beginning immediately after Italy joined the Axis in early 1939, MAS boats combined the best aspects of the innovative German E-boat hull design with the proven performance of the excellent Italian outboard motors. In an effort to showcase the cooperation between the two fascist nations, a complete E-Boat was transported overland to Genoa in early January 1939; Italian designers and engineers at Ansaldo were surprised to learn of the exotic layering of materials that went into the E-Boat’s composite hull construction (consisting of alternating layers of exotic and lightweight wood, aluminum composites, and other denser types of wood), which gave the craft considerable flexibility in different sea conditions while also providing surprising strength and durability. Most impressive of all the discoveries, however, was the German revelation of the so-called “Lürssen Effect,” which was created by adding small outboard rudders to a specially-cantilevered hull. The addition of these rudders created an air pocket in the wake of the craft at high speed that decreased drag, increased speed, decreased noise, increased fuel economy, and reduced overall visibility of the stern wake, all highly-desired aspects for a stealthy coastal patrol craft.

Side view of MAS Boat 451, emphasizing the craft’s low visibility and small size

Side view of MAS Boat 451, emphasizing the craft’s low visibility and small size

Before the collaboration, E-Boats using three 1,000 HP BMW engines were routinely achieving 40 knots in calm seas; Italian MAS boats utilizing high-performance Isotta Fraschini engines were somewhat faster but less reliable. As a result, the combination of the best traits of the two types of torpedo boats resulted in (after a few months of trial and error) a remarkable final product that, despite a few nagging issues could cruise at almost 45 knots and was almost 10-15 knots faster than anything the Allies could field at that time. Velocity of that magnitude was a defense all its own; nothing on water could hope to catch a MAS boat, and aircraft (if they could even see it against its sea grey paint scheme and low silhouette) would find them a frustratingly nimble target. Despite all of their advantages, however, MAS Boats (and E-Boats) were light-skinned and lightly-armed vessels; as a result, they were confined primarily to night missions against convoys (in which they would typically loose their pair of torpedoes and then return to base at flank speed) and to operations in calm seas (as rough chop reduced their speed dramatically). Though typically armed with light AA armament, MAS boats would not last long in a straight-up fight against real warships, and instead preferred combat against slow, unescorted convoy freighters.

A MAS Boat makes a high speed turn

Eager to employ his new weapons, and somewhat hampered by his torpedo boats relatively short range (one of their primary drawbacks), Campioni selectively interpreted his ‘patrol’ orders to mean more of a ‘vigorous search and destroy’ order as his fleet swiftly plowed into the moonlit Southern Adriatic. Campioni surmised that the British would act in a similar manner, perhaps sending a few light ships to reconnoiter the Adriatic and Aegean Seas while attempting to discern the Italian’s presence in the area. He expected no more than a few destroyers and perhaps a few light cruisers, accompanied by a few submarines, but nothing more substantial than that.

It came as a rude shock, then, when the might of the combined British Mediterranean Fleet was spotted steaming northwest by reconnaissance planes from the

Vittorio Veneto early the next morning, 6 April. As Campioni and the bridge crew listened intently to alternating periods of barely-stifled yelling and intermittent static, the recon pilot reported a vast armada consisting of at least 3 battleships, 4 heavy cruisers, numerous destroyers and corvettes, and, safely nestled in the middle of them all lied the brand-new aircraft carrier

HMS Illustrious, steaming directly for

9a Squadra at 21 knots.

HMS Illustrious was the newest aircraft carrier in the world, only recently completed the previous month and still technically undergoing sea trials before final commissioning. Built with an emphasis on survivability and with practical defenses for defending against air attack, Illustrious was the first British carrier to incorporate an armored flight deck (3”- 4” thick), eight dual-mount 4.5” AA guns, and armed to the teeth with up to 50 aircraft of varying types.

Worse for the Italians, scout planes from the

Illustrious had already spotted the

9a Squadra and radioed her position to British Admiral Cunningham’s flagship, as the northwesterly-patrolling British planes launched that morning had the benefit of flying with the rising sun at their back, illuminating the Italians while concealing their own presence. Though the fleets were still separated by over 200 miles of open water, Campioni only had time to sound for general quarters before the first British planes appeared on radar, headed directly towards

9a Squadra and only 30 miles away.

Albacore search planes launch from the Illustrious early on the 6th

Vittorio Veneto, which had been deployed for less than a year, was the only ship in the Regia Marina to possess a functional radar; as such, Campioni had selected her as his flagship before the mission began, and he immediately set about preparing his ships for the coming battle. His first action was to alert Admiral Cavagnari in Taranto to provide a situation report and request immediate air assets. Unfortunately for the Italians, due to Campioni’s rapid advance into the Adriatic the night before, he was beyond the range of friendly fighter cover. Belying this bad news, however, Cavagnari informed Campioni that he had already redirected

30a Stormo naval bomber wing, which had launched at dawn to scout the Peloponnesus Coast, to immediately change course towards the battle area. With the SM.79’s large fuel stores,

30a Stormo’s aircraft would have the range to reach the area where the naval action was anticipated to take place.

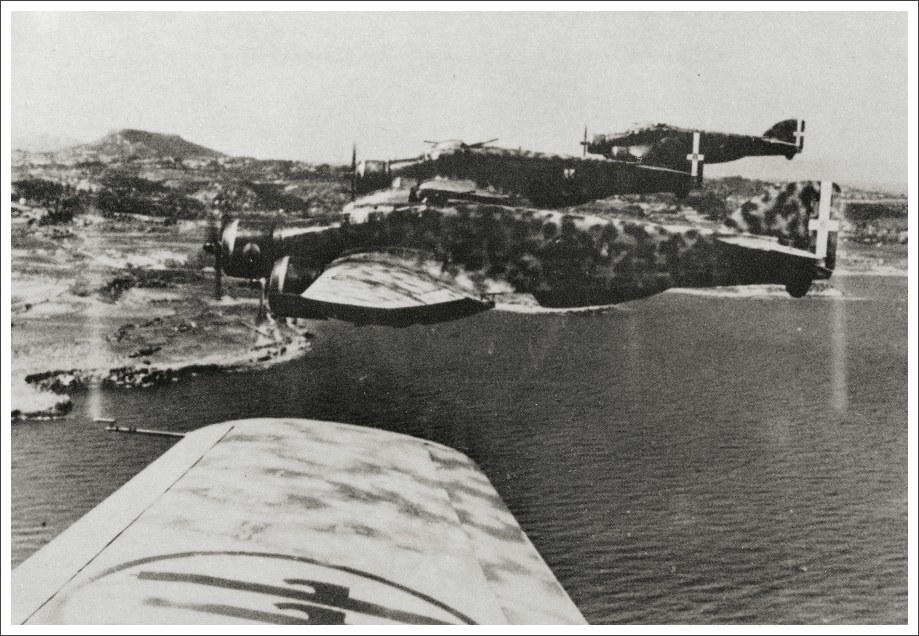

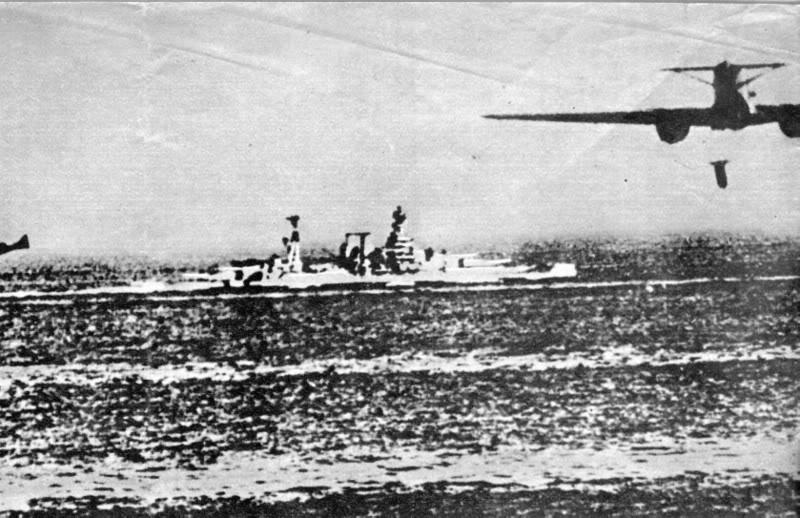

A group of SM.79 Naval Bombers swing southward towards the British Fleet

A group of SM.79 Naval Bombers swing southward towards the British Fleet

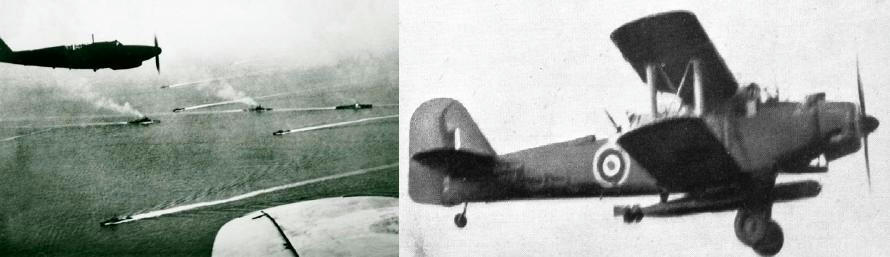

By 9:00 sunlight had filled the Mediterranean basin, and the opposing fleets, now well aware of each other’s presence, steamed ever closer towards each other. It what would later come as quite a surprise to both captains, however, the opening salvos in the upcoming battle would not be launched by ships, but by aircraft; though they had the benefit of launching their fighters first, the slow speed of the

HMS Illustrious biplane naval bombers (notably Fairey Swordfish and Albacores) allowed the quicker SM.79’s of

30a Stormo to cover the gap and intercept them before they could reach the Italian Fleet. In the ensuing melee, aircraft ill-equipped for air-to-air combat slogged it out as best they could, knowing that the victor would have the greatest chance of affecting the outcome of the coming naval battle.

The Fairey Albacore torpedo bombers (right) were the mainstay of British Fleet Air Arm naval attack squadrons. The new Fairey Fulmar’s (left) represented the latest in British monoplane design.

British Admiral Cunningham, unaware of

Vittorio Veneto’s patrol plane and anticipating a devastating first strike upon the (so he thought) unsuspecting Italians, had sent aloft almost his entire contingent of strike aircraft. 14 Albacores, 12 Swordfish, and 6 Fulmars for air support had been launched at dawn from the Illustrious and (1 each) from each of his three battleships (

HMS Warspite,

HMS Valiant, and

HMS Barham). Cunningham knew that the

Regia Marina did not have an aircraft carrier, and he justified his decision to only send along minimal fighter cover to the fact that he was initiating combat so soon after dawn, and that land based interceptors would not have time to reach the battle before its conclusion. Flying northwest in chevrons of 4 aircraft at around 140 knots, the British planes split into 2 main attack groups when they were 6 miles from the Italian Fleet and made to attack them on their flanks from both the east and west.

The prominent ‘hump’ and formidable defensive armament of the Sparviero is apparent in this flight of 2 SM.79 Naval Bombers from 229 Squadriglia, preparing to descend on the British naval bombers

Nine miles away and 5,000 feet above, the SM.79’s of

30a Stormo arrived on station just as the British bombers split in two to make their attack run. Mimicking the division of their opponents, the lumbering Italian bombers themselves split into 2 groups, each tailing one of the British formations unbeknownst to their prey . With the advantage of height, surprise, and firepower, the

Sparvieros plunged earthward into the slow moving British biplanes from above, machine guns blazing in all directions, as they scythed through the unsuspecting British.

Though unaccustomed to air superiority missions, the SM.79’s were nevertheless in an ideal situation; their planes were too fast for the British gunners to target, and the canvas wings and unarmored engines of the British biplanes were easy targets for their five machine guns. During their initial plunge through the level British formation,

30a Stormo shot down 7 total British bombers; as their hapless companions knifed into the sea, trailing long spirals of dark smoke, the balance of the British raiders broke formation, some pulling up, others barrel-rolling at oblique angles, and others simply reversing course in the crazed maelstrom. None of them had time to fire on the Italian fleet. Leveling out after their initial dive, the

Sparvieros arched gracefully around to make a second pass; on this second run, the Italian pilots were more cognizant of their markedly superior firepower, and they lazily stalked individual targets, either destroying their targets with their forward firing guns or lumbering alongside and opening up terrific broadsides from their lateral gun ports. In all cases, the British bombers were at a terrible disadvantage; only the monoplane Fulmars, whose top speed nearly matched the SM.79’s, had any chance of thwarting the relentless Italian onslaught, and they were too few to deter the slaughter.

A British Fulmar is destroyed by marauding Italian bombers

Scarcely 15 minutes after the fight began, the remaining British aircraft were all in full retreat; though the survivors dispersed at all altitudes and courses to discourage pursuit, the Italian destroyers had no interest in pursuing obsolete aircraft and exhausting their fuel reserves.

30a Stormo, having shot down 24 aircraft of all types, and more importantly, preventing the Italian fleet from a serious aerial attack, regrouped for their belated attack on the British fleet. Though their losses were light (only 2 aircraft damaged, which had to return to Taranto), the remainder were now low on fuel and nearly out of machine gun ammunition. Compounding their fuel shortage was the cumbersome weight of their 2 external 450mm torpedoes, which lowered their overall fuel economy and limited maneuverability. The flight commander therefore ordered his 16 remaining planes to attack en masse, with their primary target to be the

HMS Illustrious; the carrier would need to be taken out or disabled in order to ensure that the Italians would maintain air superiority in the coming battle, as it would take several hours for

30a Stormo to return to base to rearm and return to the battle area, a long period for a fleet to go without air cover.

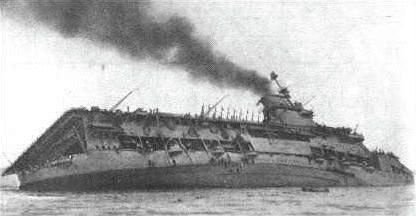

HMS Illustrious steams northwest to recover the survivors of the air battle

By this time, the British Mediterranean Fleet lied approximately 30 miles southeast of the

9a Squadra. Nearing the maximum range of their endurance,

30a Stormo’s bombers had only a few short minutes to prepare for the assault, and in the end, due to the wide area that they had covered during the pursuit of the British aircraft, the SM.79s were forced to attack in two different waves of 8 aircraft each. The first wave attached from the west; the British, forewarned by radar emplaced on many of their picket destroyers, were ready for this move, and had positioned most of their light cruisers in an arc that protected

Illustrious from attack in this direction. As a result, most of the torpedoes launched were dropped prematurely or (owing to nearby AA fire) at the wrong angle and simply fell into the sea; of the 4 torpedoes that were dropped straight and level, poor aim and frantic maneuvering on the part of

Illustrious prevented any damage to the carrier. Three SM.79’s were lost to the intense flak barrage as well, and the remaining five bombers immediately dashed north back towards Taranto.

The first 30a wave’s assault resulted in several successful launches, but no hits on any British Ships

The 2nd wave of

30a Stormo, coming in just a few minutes after the first wave, availed itself to a British fleet that was concentrating in the wrong direction. Approaching from the east, the bombers dove in low and line abreast, skimming the wavetops at 65 feet. Protecting the right flank of the British fleet were the 3 battleships and several light destroyers; the anti-aircraft power of these ships was not nearly as prolific or accurate as the light cruisers on the left flank, and many of the older battleship guns would not depress low enough to even fire on the approaching Italian bombers. Though the light cruisers

HMS Cairo,

Colombo, and

Centaur belatedly tried to take position on the right flank, furiously steaming directly through the center of the armada in an attempt to reach Illustrious in time, they were simply too far out of position to arrive in time to affect the 2nd strike. Though a lucky strike from a 4”AA gun on the heavy cruiser

HMS Cornwall destroyed one of the approaching bombers, the remaining seven continued their run and released their ordinance as intended.

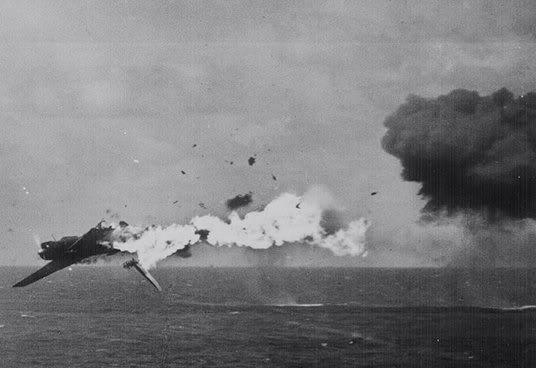

30a Stormo initiates its torpedo run against HMS Norfolk

Fourteen torpedoes snaked their way underwater towards the

Illustrious as the Italian bombers soared upwards and away from the intensifying British AA fire. Released from their heavy ordinance, the SM.79’s became much more nimble, and they climbed steadily northwards as the flak gradually dissipated behind them. From the rear turret of the trailing bomber, huge explosions could be seen and heard below; 4 torpedoes had smashed into

Illustrious’ port side, another had blown a 40 foot hole into

HMS Norfolk, and 2 more had torn into the destroyer

HMS Fury.

HMS Illustrious reels from 4 torpedo hits delivered by 30a Stormo

Fires raged throughout the empty hanger decks of the

Illustrious, and oily plumes of putrid black smoke bellowed skyward as seawater poured into enormous gashes in her port side; the great ship began listing almost immediately, and the growing tilt was only minimally compensated by flooding opposite compartments on the starboard side of the hull. Lying unconscious on the floor of the bridge, Admiral Cunningham’s contorted body lied crumpled in a corner of the room, several jagged pieces of glass from the bridge windshield (blown apart by the concussive force of the torpedo impacts) threatening to sever arteries in his neck and legs. He was in better shape than most of the bridge crew, however; most of the other officers had been killed outright during the quick succession of torpedo impacts. Equally unfortunate,

HMS Fury had been obliterated by simultaneous torpedo explosions, and

HMS Norfolk was dead in the water, afloat but effectively out of action. Damage control teams thought

Illustrious could still be saved, but she was drifting without power and, due to the listing of her flight deck, could not deploy or recover aircraft.

HMS Fury ceases to exist

As they passed back over the Italian fleet on their way back to Taranto,

30a Stormo’s commander radioed to Campioni that the British Fleet was now without air cover, and ‘missing’ a few other ships as well. Campioni acknowledged the message but remained pensive for several moments afterwards, considering his options.

Thanks to his land-based aircraft, he had dodged a particularly nasty bullet in neutralizing the British advantage in airpower; Italy would be best served by utilizing their superior speed and withdrawing from the battle area, content with the significant damage to the British Mediterranean Fleet that they had caused yet still cognizant of the powerful British firepower advantage arrayed by their heavier battleships and cruisers.

However, he

could press his advantage, taking advantage of the no-doubt confused mess that would now be gripping the British following the loss of their flagship and (perhaps, he thought) even their commander as well…

A nearby aide, perplexed by the Admiral’s curious silence, coughed lowly in Campioni’s direction, as if to ask what his new orders were.

Several more minutes passed, and then, ever so subtly, a wry, thin smile corkscrewed up Campioni’s face as he said “Flank speed, course bearing 155.”

Would the loss of HMI Illustrious even the odds?

Would the loss of HMI Illustrious even the odds?