Siegerkranz - Germany's Place in the Sun

- Thread starter c0d5579

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Is it that obvious where young Peter is headed?

Seriously, though, I fully intend to get the entire Volkmann family fully engaged, soon as they get around to graduating.

Seriously, though, I fully intend to get the entire Volkmann family fully engaged, soon as they get around to graduating.

Is it that obvious where young Peter is headed?

Seriously, though, I fully intend to get the entire Volkmann family fully engaged, soon as they get around to graduating.

Well, it's Kurt Student. You could have used anyone from Adolf Galland over Hugo Sperrle to Milch if you just wanted to get him into the Luftwaffe, whereas Stundent is a clear pointer to Paras.

Well, it's Kurt Student. You could have used anyone from Adolf Galland over Hugo Sperrle to Milch if you just wanted to get him into the Luftwaffe, whereas Stundent is a clear pointer to Paras.

You'd think that, but Student was a WW1 fighter pilot, and head of the Luftwaffe's schools and training program before suggesting anyone leap out of a perfectly good airplane. In all seriousness, though, there's a long road before Germany starts fielding paratroopers.

You'd think that, but Student was a WW1 fighter pilot, and head of the Luftwaffe's schools and training program before suggesting anyone leap out of a perfectly good airplane. In all seriousness, though, there's a long road before Germany starts fielding paratroopers.

Oh I agree, but it's perfectly obvious that if Student is mentioned so prominently, it has to have something to do with Paras.

5. Birthdays and Beginnings

27 January 1934

27 January 1934

Berlin, Republic of Germany

Chancellor von Schleicher suppressed a yawn - not because he was bored, though he was, but because these functions inevitably lasted forever, and it was now well past ten in the evening. "These functions" were an annual habit among the older generation of officers: the birthday of His Imperial and Royal Majesty Wilhelm the Second, By the Grace of God, German Emperor and King of Prussia, Margrave of Brandenburg, Burgrave of Nuremberg, Count of Hohenzollern, Duke of Silesia and of the County of Glatz, Grand Duke of the Lower Rhine and of Posen, Duke of Saxony, of Angria, of Westphalia, of Pomerania and of Lunenburg, Duke of Schleswig, of Holstein and of Crossen, Duke of Magdeburg, of Bremen, of Guelderland and of Jülich, Cleves and Berg, Duke of the Wends and the Kashubians, of Lauenburg and of Mecklenburg, Landgrave of Hesse and in Thuringia, Margrave of Upper and Lower Lusatia, Prince of Orange, of Rugen, of East Friesland, of Paderborn and of Pyrmont, Prince of Halberstadt, of Münster, of Minden, of Osnabrück, of Hildesheim, of Verden, of Kammin, of Fulda, of Nassau and of Moers, Princely Count of Henneberg, Count of the Mark, of Ravensberg, of Hohenstein, of Tecklenburg and of Lingen, Count of Mansfeld, of Sigmaringen and of Veringen, Lord of Frankfurt... as the honorary herald had insisted on reading off when announcing the intended occupant of the seat of honor at the head table.

Schleicher sat to the left of the empty throne, as befit the nominally second most powerful man in Germany today; to the immediate right sat the eldest Hohenzollern still allowed in Germany, Kronprinz Wilhelm. To his right sat the elder Hindenburg, much more comfortable with the Kronprinz than Schleicher was and as ever deferring to the monarchists. On Schleicher's left sat the War Minister, General von Hammerstein-Equordt, and past him the Reichsmarine commander, Admiral Raeder. Behind them, Wilhelm's official portrait hung in black bunting, a reminder that he was in exile. Out in front of him were the elite of the German establishment - the families Krupp, Siemens, and Thyssen with their representatives, every flag officer in the Reichswehr, and every member of "the good set" who could afford to turn up. It was all Schleicher's doing; he had decided to woo the conservatives again, and thus it was that Germany's vice-chancellor had not found himself invited to an event thrown by Germany's President and Chancellor. Strasser would, Schleicher thought smugly, have been sadly out of place in this gathering... but then, where was Gregor Strasser in place?

That was why Germany's elite were gathered in the Chancellory on a January evening, dining from the finest china and silver that Schleicher could muster. Normally this would have been done at some other location, but he had a feeling that if he had let that happen, he would not have been invited, either. The conservatives were still intensely suspicious of him, despite his suppression of practically every political party which could object to their agenda. The only surviving parties outside the nationalist-monarchist coalition were Strasser's Social Nationalists and the Catholic Center... and only von Papen was saving them.

Schleicher waited through another round of toasts, the crowd more than a little tipsy at this point, before standing, holding his own glass. "Ladies! Gentlemen! Your attention, please!" The room quieted, and he finally began the address he had been preparing all night for.

"Six months ago, Captain Patzig - thank you, Patzig, you may be seated - told me that half of all Germans wanted to see me removed from office and put on trial. Today, he tells me that number is down to one in ten." He gave a thin smile, followed by equally thin applause, brandy held high still. "I want you all to know that - and to know that it is not my purpose to turn Germany into a dictatorship. A dictatorship lacks the authority of the Almighty, and it lacks the blessings of the people; as such, it cannot stand past its hour. As the Kronprinz can attest, the Almighty's protection is no sure guarantee either, and as our recent comrades Hitler and Thaelmann can unhappily tell you, the people are fickle. Who today seriously considers a Nazi return, or a Red rising, as plausible? Still, wheels turn, and what would have been unthinkable in 1930 is believable now... see our beloved Kronprinz, allowed by our French cousins to attend a gathering in his father's honor. Soon, he will require no one's permission.

"Germany is stable for the first time in years. We are not strong, but we are healing, and we can see a day when we will be strong. We have begun to rearm - I break no confidences here when I tell you that Germany in five years will be free of the military and economic restrictions forced upon us, and in ten years free of the territorial restrictions. I have served at the President's pleasure, and it pleases me that he continues to trust me. Prince William, if I may..." Schleicher set his glass down, turning to face the missing Kaiser's portrait, and in a nasal, flat voice, began to sing. The words came easily enough, but he was surprised at how much they meant to him, even after all these years.

"Heil dir im Siegerkranz,

Herrscher des Vaterlands,

Heil, Kaiser, dir..."

The room came to their feet; they would hardly be here if they did not agree with the sentiment. Their assembled voices joined his, drowning it out, and out of the corner of his eye, Schleicher saw both Hindenburg and Wilhelm's eyes glistening. On this one point, apparently, field marshal and general agreed.

---

Three weeks of ground school had left Peter Volkmann with a burning desire to get into the air. Finally the day had come; the four students who had pseudo-official backing in the THB flying club had gathered at dawn on the twenty-third, given their professors their absence notice, and taken an Air Ministry truck to the field at Stendal, a hundred miles west of the city. They had been introduced to their first "crates" the following day: relatively modern Fw 44 biplane trainers. This was the same plane, they were told by serious-faced men in greasy black coveralls, that men like Udet and Achgelis flew at events like the Luftsportstag. It behooved them, future pilots of the eventual German air force, to take care of it. After weeks of being sworn to secrecy and of being told they were in at the beginning of a great movement, the cadets lapped it up - Volkmann included, he had to admit during the few hours a day where he got any time for introspection. They had spent the last few days in intensive flight training, and today was, by all accounts, The Day.

They had woken, as usual, before dawn to the sound of a bugle. This was still enough of an adventure that he had not yet learned to hate the bugle as his father did. The early morning hours had been filled with weather briefings for the day - cold, but clear; perfect flying weather as far as the machines were concerned. A quick walkaround of the planes had accompanied the sunrise, and now, at about nine, it was time to start the engines. The four of them each had an observer aircraft to fly alongside them, but they would be alone in the planes. Volkmann was third in the takeoff order, meaning he had a few minutes longer to spin the aircraft up. The engine sounded good, the chocks moved clear with no sign of frost, and the plane rolled easily out to the taxiway, where he kept the engine idle as he watched the others complete their takeoff rolls. It was his turn at last.

Flaps down, throttle open... rolling... good, good... takeoff speed, bring the nose down a little... and... we're up! Volkmann tore his eyes from the controls, looking over the side to see the ground blurring past beneath him... and realized that the goggles were tearing away from his face. He wrestled with them for a moment before leveling the plane out and bringing it around, waggling to show he was all right. His observer came along level beside him, and the day's training began in earnest.

By the end of the day, he had logged an additional five hours of flight time; he checked his logbook, and he was halfway to the required minimum of forty hours. One ritual remained; the ground crew met him before the plane had even fully stopped, grinning like maniacs, with a pair of shears. He knew what was coming. He also knew what was expected - he bolted from the cockpit, peeling one of the ground crew away to chock it down as the new solo pilot made a break for the woodline. The instructors landed shortly thereafter, doubling the number of chasers as he looked back... and promptly tripped, falling face-first into the cold grass. The ground crew and instructors pounced on him, cackling and howling as they sheared away his shirt. He laughed along with them, his role in the festivities complete, before standing up, shivering in the cold. Someone - he did not even see who - presented him with a fresh, un-wrinkled new leather jacket.

"Welcome to the air force that doesn't exist, fresh meat." This time, it was clearer who it was - the highest-ranking man currently at Stendal and the man in charge of the 'testing and development' unit, Hauptmann Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen. "We're going to need more like you." Volkmann stood, stumbling, and saluted as best he could with only the front half of his shirt. He could already see the back half being nailed to the side of the field's wooden hanger. "Sir!" Richthofen waved the salute away, extending a hand instead. "I remember my first. Today's your day, enjoy it while it lasts." Volkmann pumped the old pilot's hand, as dazzled by the famous name as by the events of the day, stammering out his name. "Well then, Peter... get a move on, put that jacket on, and for God's sake, if your head isn't killing you in the morning, I'll want to know why!"

---

Essen, Republic of Germany

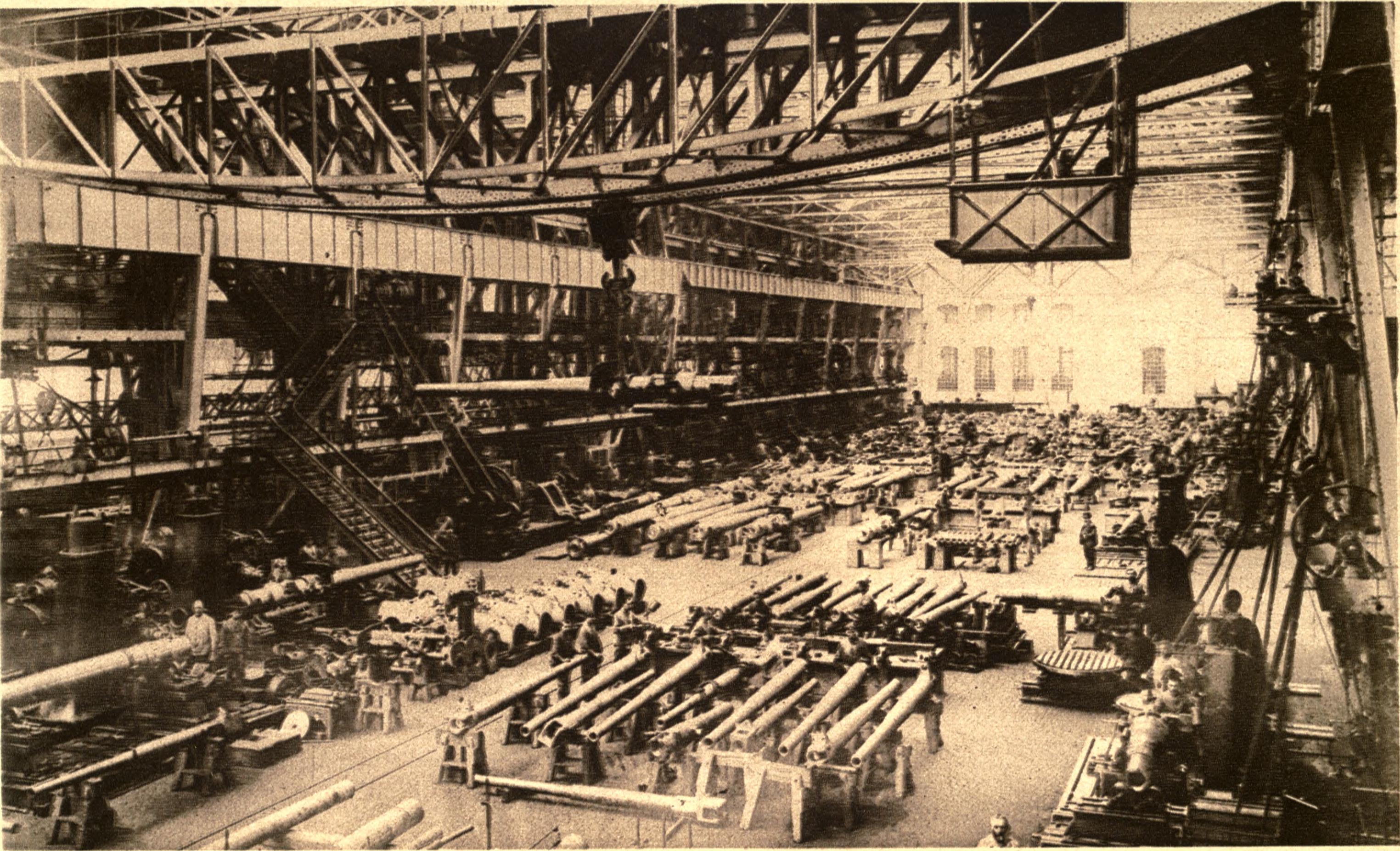

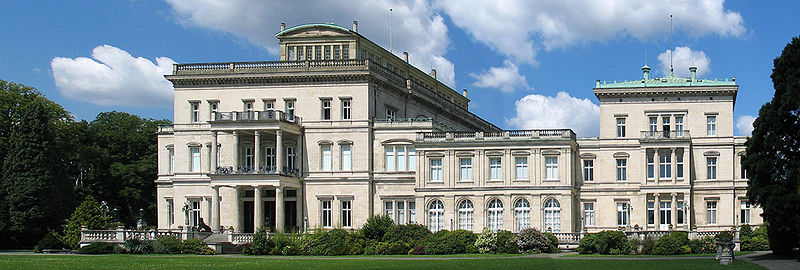

Ernst Volkmann was at a loss. He had proceeded to Essen in keeping with his orders, but once he had arrived, had been informed about the project with which he was supposed to be assisting. His protests - that he knew nothing about artillery or engines - fell on mostly-deaf ears. The exception had proven to be old man Krupp's son Alfried, currently in Berlin for some soiree or somesuch. Alfried had pulled Volkmann aside from the main engineering delegation, most of whom were currently at the proving ground in Meppen, and put him to work on a problem he understood much better: trains.

The problem was that the new tanks had to reach the front somehow, but loaded on trains, they were slightly too high for most tunnels. This was not a problem in northern Germany, but in the Bavarian Alps it could be an issue. Volkmann had begun to approach the problem, but he was still facing other issues - finding a place to live in the tight-knit Kruppianer community, working out whether Krupp now paid his salary, or the Reichswehr, worrying about Peter...

He shook his head, returning his attention to the drafting table. To transport these tanks by train would require a lower car, but that created problems of wheel clearance. If the car could be lengthened... Volkmann thought he saw a potential solution, feverishly brushing away eraser rubber before drawing a series of thin straight-edge lines. He grabbed one of the assistant draughtsmen, pulling him away from his work. "Emil, what do you think?"

Emil studied the sketch, craning his head. "Wouldn't know, sir, you need one of the railway people. I'm actually in consumer goods, just got seconded over here with the... Meppen project." The Kruppianer looked at him with insular suspicion before Volkmann clapped him on the shoulder. "Just between us, Emil, that's how I wound up here too." A yawn, stretching, then he returned to the matter at hand. "All right, Emil, you know who to talk to, do me a favor? Make sure this gets to the rail line regulars." Emil nodded, and Volkmann returned to his drafting, determined to have something close to a finished sketch before going home.

Berlin, Republic of Germany

Chancellor von Schleicher suppressed a yawn - not because he was bored, though he was, but because these functions inevitably lasted forever, and it was now well past ten in the evening. "These functions" were an annual habit among the older generation of officers: the birthday of His Imperial and Royal Majesty Wilhelm the Second, By the Grace of God, German Emperor and King of Prussia, Margrave of Brandenburg, Burgrave of Nuremberg, Count of Hohenzollern, Duke of Silesia and of the County of Glatz, Grand Duke of the Lower Rhine and of Posen, Duke of Saxony, of Angria, of Westphalia, of Pomerania and of Lunenburg, Duke of Schleswig, of Holstein and of Crossen, Duke of Magdeburg, of Bremen, of Guelderland and of Jülich, Cleves and Berg, Duke of the Wends and the Kashubians, of Lauenburg and of Mecklenburg, Landgrave of Hesse and in Thuringia, Margrave of Upper and Lower Lusatia, Prince of Orange, of Rugen, of East Friesland, of Paderborn and of Pyrmont, Prince of Halberstadt, of Münster, of Minden, of Osnabrück, of Hildesheim, of Verden, of Kammin, of Fulda, of Nassau and of Moers, Princely Count of Henneberg, Count of the Mark, of Ravensberg, of Hohenstein, of Tecklenburg and of Lingen, Count of Mansfeld, of Sigmaringen and of Veringen, Lord of Frankfurt... as the honorary herald had insisted on reading off when announcing the intended occupant of the seat of honor at the head table.

Schleicher sat to the left of the empty throne, as befit the nominally second most powerful man in Germany today; to the immediate right sat the eldest Hohenzollern still allowed in Germany, Kronprinz Wilhelm. To his right sat the elder Hindenburg, much more comfortable with the Kronprinz than Schleicher was and as ever deferring to the monarchists. On Schleicher's left sat the War Minister, General von Hammerstein-Equordt, and past him the Reichsmarine commander, Admiral Raeder. Behind them, Wilhelm's official portrait hung in black bunting, a reminder that he was in exile. Out in front of him were the elite of the German establishment - the families Krupp, Siemens, and Thyssen with their representatives, every flag officer in the Reichswehr, and every member of "the good set" who could afford to turn up. It was all Schleicher's doing; he had decided to woo the conservatives again, and thus it was that Germany's vice-chancellor had not found himself invited to an event thrown by Germany's President and Chancellor. Strasser would, Schleicher thought smugly, have been sadly out of place in this gathering... but then, where was Gregor Strasser in place?

That was why Germany's elite were gathered in the Chancellory on a January evening, dining from the finest china and silver that Schleicher could muster. Normally this would have been done at some other location, but he had a feeling that if he had let that happen, he would not have been invited, either. The conservatives were still intensely suspicious of him, despite his suppression of practically every political party which could object to their agenda. The only surviving parties outside the nationalist-monarchist coalition were Strasser's Social Nationalists and the Catholic Center... and only von Papen was saving them.

Schleicher waited through another round of toasts, the crowd more than a little tipsy at this point, before standing, holding his own glass. "Ladies! Gentlemen! Your attention, please!" The room quieted, and he finally began the address he had been preparing all night for.

"Six months ago, Captain Patzig - thank you, Patzig, you may be seated - told me that half of all Germans wanted to see me removed from office and put on trial. Today, he tells me that number is down to one in ten." He gave a thin smile, followed by equally thin applause, brandy held high still. "I want you all to know that - and to know that it is not my purpose to turn Germany into a dictatorship. A dictatorship lacks the authority of the Almighty, and it lacks the blessings of the people; as such, it cannot stand past its hour. As the Kronprinz can attest, the Almighty's protection is no sure guarantee either, and as our recent comrades Hitler and Thaelmann can unhappily tell you, the people are fickle. Who today seriously considers a Nazi return, or a Red rising, as plausible? Still, wheels turn, and what would have been unthinkable in 1930 is believable now... see our beloved Kronprinz, allowed by our French cousins to attend a gathering in his father's honor. Soon, he will require no one's permission.

"Germany is stable for the first time in years. We are not strong, but we are healing, and we can see a day when we will be strong. We have begun to rearm - I break no confidences here when I tell you that Germany in five years will be free of the military and economic restrictions forced upon us, and in ten years free of the territorial restrictions. I have served at the President's pleasure, and it pleases me that he continues to trust me. Prince William, if I may..." Schleicher set his glass down, turning to face the missing Kaiser's portrait, and in a nasal, flat voice, began to sing. The words came easily enough, but he was surprised at how much they meant to him, even after all these years.

"Heil dir im Siegerkranz,

Herrscher des Vaterlands,

Heil, Kaiser, dir..."

The room came to their feet; they would hardly be here if they did not agree with the sentiment. Their assembled voices joined his, drowning it out, and out of the corner of his eye, Schleicher saw both Hindenburg and Wilhelm's eyes glistening. On this one point, apparently, field marshal and general agreed.

---

Three weeks of ground school had left Peter Volkmann with a burning desire to get into the air. Finally the day had come; the four students who had pseudo-official backing in the THB flying club had gathered at dawn on the twenty-third, given their professors their absence notice, and taken an Air Ministry truck to the field at Stendal, a hundred miles west of the city. They had been introduced to their first "crates" the following day: relatively modern Fw 44 biplane trainers. This was the same plane, they were told by serious-faced men in greasy black coveralls, that men like Udet and Achgelis flew at events like the Luftsportstag. It behooved them, future pilots of the eventual German air force, to take care of it. After weeks of being sworn to secrecy and of being told they were in at the beginning of a great movement, the cadets lapped it up - Volkmann included, he had to admit during the few hours a day where he got any time for introspection. They had spent the last few days in intensive flight training, and today was, by all accounts, The Day.

They had woken, as usual, before dawn to the sound of a bugle. This was still enough of an adventure that he had not yet learned to hate the bugle as his father did. The early morning hours had been filled with weather briefings for the day - cold, but clear; perfect flying weather as far as the machines were concerned. A quick walkaround of the planes had accompanied the sunrise, and now, at about nine, it was time to start the engines. The four of them each had an observer aircraft to fly alongside them, but they would be alone in the planes. Volkmann was third in the takeoff order, meaning he had a few minutes longer to spin the aircraft up. The engine sounded good, the chocks moved clear with no sign of frost, and the plane rolled easily out to the taxiway, where he kept the engine idle as he watched the others complete their takeoff rolls. It was his turn at last.

Flaps down, throttle open... rolling... good, good... takeoff speed, bring the nose down a little... and... we're up! Volkmann tore his eyes from the controls, looking over the side to see the ground blurring past beneath him... and realized that the goggles were tearing away from his face. He wrestled with them for a moment before leveling the plane out and bringing it around, waggling to show he was all right. His observer came along level beside him, and the day's training began in earnest.

By the end of the day, he had logged an additional five hours of flight time; he checked his logbook, and he was halfway to the required minimum of forty hours. One ritual remained; the ground crew met him before the plane had even fully stopped, grinning like maniacs, with a pair of shears. He knew what was coming. He also knew what was expected - he bolted from the cockpit, peeling one of the ground crew away to chock it down as the new solo pilot made a break for the woodline. The instructors landed shortly thereafter, doubling the number of chasers as he looked back... and promptly tripped, falling face-first into the cold grass. The ground crew and instructors pounced on him, cackling and howling as they sheared away his shirt. He laughed along with them, his role in the festivities complete, before standing up, shivering in the cold. Someone - he did not even see who - presented him with a fresh, un-wrinkled new leather jacket.

"Welcome to the air force that doesn't exist, fresh meat." This time, it was clearer who it was - the highest-ranking man currently at Stendal and the man in charge of the 'testing and development' unit, Hauptmann Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen. "We're going to need more like you." Volkmann stood, stumbling, and saluted as best he could with only the front half of his shirt. He could already see the back half being nailed to the side of the field's wooden hanger. "Sir!" Richthofen waved the salute away, extending a hand instead. "I remember my first. Today's your day, enjoy it while it lasts." Volkmann pumped the old pilot's hand, as dazzled by the famous name as by the events of the day, stammering out his name. "Well then, Peter... get a move on, put that jacket on, and for God's sake, if your head isn't killing you in the morning, I'll want to know why!"

---

Essen, Republic of Germany

Ernst Volkmann was at a loss. He had proceeded to Essen in keeping with his orders, but once he had arrived, had been informed about the project with which he was supposed to be assisting. His protests - that he knew nothing about artillery or engines - fell on mostly-deaf ears. The exception had proven to be old man Krupp's son Alfried, currently in Berlin for some soiree or somesuch. Alfried had pulled Volkmann aside from the main engineering delegation, most of whom were currently at the proving ground in Meppen, and put him to work on a problem he understood much better: trains.

The problem was that the new tanks had to reach the front somehow, but loaded on trains, they were slightly too high for most tunnels. This was not a problem in northern Germany, but in the Bavarian Alps it could be an issue. Volkmann had begun to approach the problem, but he was still facing other issues - finding a place to live in the tight-knit Kruppianer community, working out whether Krupp now paid his salary, or the Reichswehr, worrying about Peter...

He shook his head, returning his attention to the drafting table. To transport these tanks by train would require a lower car, but that created problems of wheel clearance. If the car could be lengthened... Volkmann thought he saw a potential solution, feverishly brushing away eraser rubber before drawing a series of thin straight-edge lines. He grabbed one of the assistant draughtsmen, pulling him away from his work. "Emil, what do you think?"

Emil studied the sketch, craning his head. "Wouldn't know, sir, you need one of the railway people. I'm actually in consumer goods, just got seconded over here with the... Meppen project." The Kruppianer looked at him with insular suspicion before Volkmann clapped him on the shoulder. "Just between us, Emil, that's how I wound up here too." A yawn, stretching, then he returned to the matter at hand. "All right, Emil, you know who to talk to, do me a favor? Make sure this gets to the rail line regulars." Emil nodded, and Volkmann returned to his drafting, determined to have something close to a finished sketch before going home.

Last edited:

6. Messerschlacht

28 February 28 1934

Essen, Republic of Germany

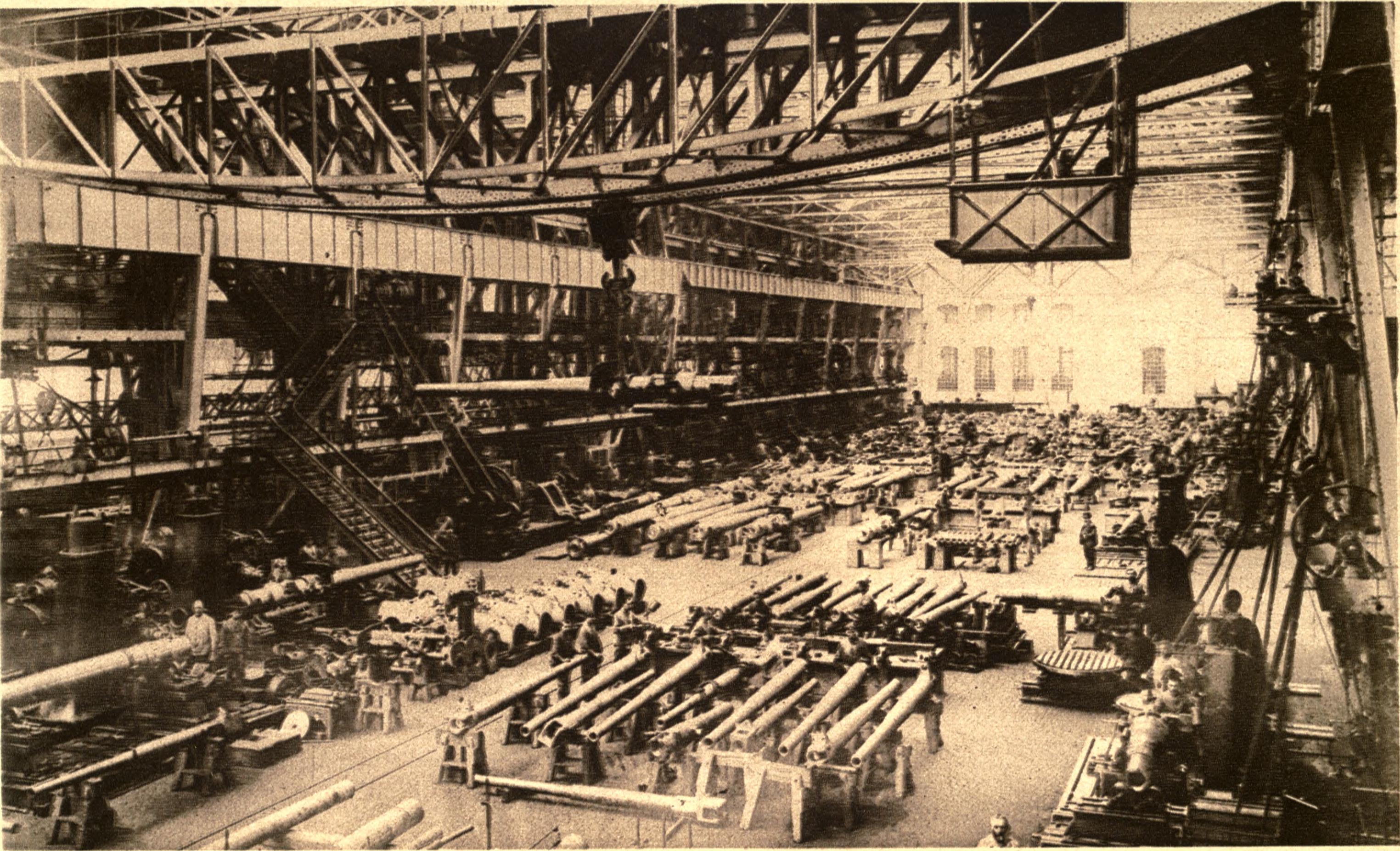

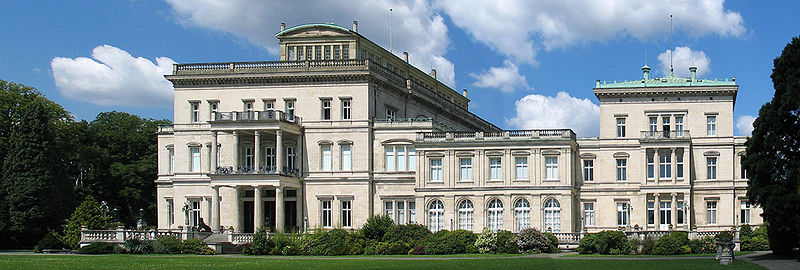

This was not Schleicher's first visit to the Villa Huegel, but it was his first as Chancellor. The vast edifice, built to represent Germany's growing industrial power in the 1870s, was the Krupp family castle, as Schloss Hohenzollern was sacred to Germany's imperial family even in their exile. Nevertheless, it had been built deliberately just out of sight of the great steel foundries, on a landscape kept immaculate even through the lean years from 1929 to now. He had been met at the door by old Gustav's firstborn, Alfried. "Fair warning, the old man is on the attack today," Alfried murmured around his ever-present cigarette, freshly lit from the end of his last. Schleicher gritted his teeth. "I can understand why, Herr Bohlen."

A week prior, Strasser had opened his mouth on the radio. The Vice-Chancellor, stung at his omission from the Kaiser's birthday celebration, had called for the nationalization of all heavy industry, all of the investment banks, and all of the great Junker landholdings, and, even more outrageously, for the reformation of the Nazi paramilitary corps, the 'Sturmabteilung,' in order, as he put it, "to carry the great German revolution to the Judeo-Bolsheviks in Moscow." It was an unapologetically revolutionary program, and Schleicher had been forced to a number of meetings such as this one - he had spent hours in the Truppenamt reassuring Junker officers left and right that their estates were safe while he lived, he had just come from Thyssen's Swiss estate at Lake Lugano, and he expected to spend the rest of the week, possibly longer, personally meeting with Germany's great men, reassuring them regarding the rapidly widening split between the pragmatic Chancellor and his new nemesis.

In the great conference room, Gustav Krupp waited, back to his approaching guest. Krupp emanated polite fury, not bothering just yet to turn to greet Schleicher. "Chancellor," he began without preamble, "what is the meaning of this nationalization nonsense?"

"Herr Krupp, Strasser spoke without consulting me. He does not speak for Germany -"

"Of course he does not speak for Germany. Krupp speaks for Germany. What is good for Krupp is good for the Reich!" Gustav whirled and bellowed. Even Alfried was shocked at this display - to see an old-fashioned diplomat like Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach explode thus was unheard of. To his credit, Schleicher stood his ground. "Just so, Herr Krupp. I agree completely, which is why I, and not an infantry battalion, am in your house. If I stood with Strasser in this, do you think I would be here?"

"Schleicher, we both know that you'd gladly cut your own mother's throat if you thought it'd put you in the President's office." The flat declaration from Krupp was, perhaps, the most blunt, vulgar thing that the old man had ever uttered. "Let us not kid ourselves. I cooperate with you because you disposed of the Reds, and of the Nazis with their Roehm madness. What I cannot understand is how you decided, having rid Germany of that filth, that Gregor Strasser was an acceptable alternative. Even Bruening would have been better."

"As long as we are speaking frankly... Krupp," Schleicher ground out, "Bruening does not believe in the great guns. Those toy cars you have at Meppen? Bruening, God be thanked, does not know of them, because if he did, he would run crying to the disarmament conference. I work with the tools I find at hand. Strasser was the best of a number of bad choices; he split the Nazis and gave us just enough edge to get through last year. I shudder to think of what would have happened without Strasser confusing that Austrian corporal the Nazis call 'Fuehrer.'" Schleicher practically spat the last word.

"And what of this company of thugs you have hidden up at Meppen?" Krupp demanded angrily, cane thumping the tile floor with each syllable.

Schleicher sighed. "Krupp, can we talk about this like sane men rather than gorillas?" He cleared his throat. "I've been living in rail cars for two weeks talking to every rich man who feels Strasser is eyeing his land, his money, or his bank. I even spent an afternoon speaking to the head rabbi of the Berlin synagogue. I have far better ways to spend my time than speaking to a rabbi for an afternoon." Krupp was still bristling, but no longer looked as if he wished to lunge for his throat. "Very well. Alfried! Chairs, please, and join us."

Momentarily, chairs were brought, and the three of them sat, free of observation save for Ott, unobtrusively posted near the door. "You wanted to know about my company of thugs at Meppen," Schleicher said mildly. Krupp nodded sharply, so Schleicher continued. "Most of those men were members of Hitler's organization, as you may have noticed. They have no love of Strasser, which is why I preserve them. However, they, or at least the ringleaders, were more loyal to Germany than the Bavarian corporal." He drummed his fingers on his armrest, eyes gazing at nothing in speculation. "So I preserve them, even offered one of them a position as a tank evaluation officer. That's your Hauptmann Dietrich. Not really our sort, but a good enough soldier, and he does know his way around tanks." He frowned. "Of course, Dietrich's personnel choices sometimes bother even me. His first sergeant... this man Eicke... is the Devil incarnate."

Krupp interrupted his reverie. "Yes, but why are you preserving them?"

"Because if the time comes to deal with Strasser, I need men who already hate him, who are not linked to the Army, and who are not afraid of violence." Schleicher looked directly at Krupp, voice flat, before proceeding. "And, Herr Krupp... I assure you that the question is no longer 'if,' but 'when.'"

---

15 May 1934

Stendal, Republic of Germany

Peter Volkmann awoke with a groan as the bugle went off. He had reported to Stendal once more as soon as his clases were complete for a summer's worth of military training. He was not, as he had thought, something special for his pilot's qualifications; he was, rather, as the platoon sergeant had gleefully informed him, scum, for wanting a commission. Until he had shown he was something other than a creature unfit to crawl through the muck of the Earth, he was a cadet, not even marked as a proper non-commissioned officer because of his special ranks.

The thirty officer candidates of his training platoon roused themselves; after a week of this, they were thoroughly trained to get out of their racks before the rack, and their world, collapsed under Feldwebel Koller's blows. Peter had expected, with his technical background and completed private pilot's license, to be something special here. In both cases, he was disappointed. To his right was a pilot... or so he claimed... whose stories of aerial derring-do generally seemed to end with "And anyway, the crate broke up on landing. Hell of a way to spend the weekend." How Cadet Galland had managed to survive this long was a mystery - he had broken up his second aircraft on landing just a month prior, and it was still unclear how he had persuaded Lufthansa that they should put him on leave for this course. It was Galland, rather than Volkmann, who had quickly developed a reputation as the standout, for Galland had logged far more hours in the air than anyone else here, and "Dolfo" Galland was studiously unimpressed by the platoon sergeant, the company commander, or indeed the only man with a car on post, now-Major von Richtofen.

Galland ostentatiously rubbed his eyes, yawning loudly. "Christ on a bicycle, Koller," he drawled, "how the hell do you expect us to fly on four hours of sleep?" Koller pounced, almost punching Galland instinctively. "Shut up, Galland. I hear another word out of you today, it'll be your last. Understand?" Galland responded with a very loud "Mmmmmmrph," lips prominently closed. Koller, frustrated by the letter-of-the-law obedience to orders, was forced to content himself with stalking away.

Volkmann muttered across to Galland, "Jesus, Dolfo, you're going to get yourself killed before graduation."

"Don't be crazy, Petie. I've been flying for four years, I've got more'n a hundred hours... even Koller's not stupid enough to kill a pilot who knows what he's doing." Volkmann envied the younger man - Galland was fifteen months younger than he was - who had gone straight from gymnasium to Lufthansa pilot's school. The cadets spent the rest of the morning in silence, punctuated by Koller's abuse, calisthenics, and, far too late, breakfast. They had, of course, arrived with only five minutes remaining before the mess closed; as a result, they had only minutes to ram down their too-small breakfast before continuing on with training. "Training," as it turned out, consisted very little of aerial warfare, and a lot more of marching, crawling, gas drills... anything, in short, to get them adjusted to life in uniform without spending expensive aviation fuel. At the end of it, as at the end of every "day" - they ended before midnight, but only by seconds - he passed out, exhausted, but with a shined pair of puttees under his bunk and the cleanest of his field uniforms hanging from the end.

It was a six-week camp, after which they graduated to the coveted status of "Under-Officers," signalling their transition into the commissioning program. It was, by Stendal's limited scope, a splendid occasion, with a small band, the first appearance of the cadets in their blue uniforms, and the issue of an officer candidate's dagger to each man. At the culmination of the ceremony, a flight of twin-engine Dornier 'mail planes' roared in low over the field, causing the unwary to lose their headgear. At the end of the camp, Major von Richtofen sat down with each of them for a few minutes for a brief interview, including a record of the new officer candidate's choice of assignment. "Dolfo" Galland had made his choice quite clear - the candidates in the hallway had heard him exclaiming, "Fighters, damn it, where the action is!" even before his interview had properly commenced.

When Volkmann got his turn, Richtofen was rubbing his forehead, frowning. This was, Volkmann thought, one disadvantage of a name at the end of the alphabet. "Volkmann. Peter, isn't it? Sit down," Richtofen said absently, opening Peter's file.

"So, Unteroffizier Volkmann. First off - congratulations." Richtofen offered a genuinely warm smile and a handshake, just as he had the day Peter had soloed. "Seems like you spend a lot of time here, time to get you a proper duty assignment. You have any preferences?"

"Well, sir... what are my choices?"

"Since you're rated as a pilot, fighters and bombers, really. Fighters are likely to get all the glory, but no one is going to win a war with fighters. We can lose one without them, but we'll never win one with them." Richtofen tapped his pen on the desk thoughtfully before continuing. "There are two types of bombers... dive bombers, which, frankly, are pilot-killers, and level bombers, like the new Dornier you got to see earlier. Personally, I think the Dornier is the weapon of the future. Your friend Galland," Richtofen noted with a quirk of his mouth, "disagrees vehemently."

"If it's all the same, sir... I'll stick with Dolfo." Volkmann shifted, uncomfortable with even the hint of disagreement with Richtofen, who, in addition to his name, was much more likeable than most officers of his age. Richtofen reminded him of his father; they were both engineers by training, they were of similar age, and only background and lineage had really separated their fates. Richtofen sighed, shook his head, and made a note in the file. "The fighter course it is... from here, you're going to Doeberitz to complete your flight training. You'll be traveling with Unteroffizier Galland, you'll be happy to know." Richtofen straightened up, continuing the interview. "Now... how're your studies going? Colonel Student asked. You'll be happy to know he remembered you... he's back from Russia, along with everyone else."

"Oh, they're going very well, thank you. I'm in General Becker's explosives chemistry class for next semester, and he has offered me a position as grader for the fall introductory ballistics course. It doesn't pay much, but I understand it covers my cadet stipend." He looked faintly embarrassed talking about money, but Richtofen grinned. "Good for you. I damn near broke myself, and that as on an embassy budget, back in Italy in '30. Volkmann... may I ask you a question?" Volkmann blinked, not expecting this level of familiarity from the most remote figure on base. "Certainly, sir."

"Why'd you choose to be a pilot, especially for us? I mean, you could've gone and worked for... oh, I don't know, Henschel has a big plant they're putting up on the other side of Berlin." Richtofen leaned across his desk, awaiting Peter's answer. Peter shrugged diffidently. "I don't know. Colonel Student made a big impression, I guess. Talked about his War experience, told me that the air was where it'd all be figured out next war. That, and it seemed like where I could use what General Becker was teaching. It's all geometry and physics in the air, not like on the ground." Richtofen shook his head, leaning back. "All wrong, Volkmann. In the air, you fight by instinct, not scientifically. Never mind what Boelcke nailed to his office door, the big rule is bring your crate home."

They continued in a surprisingly informal interview for several minutes before Richtofen looked up at the clock. "Behind schedule, Peter. Better grab your gear and get out before Koller locks up the barracks. He has this week off, you know..."

At that moment, Koller himself, as if a genie, burst into the small, stuffy office, barely remembering to salute. "Sir! There's been an attempt on the Chancellor!"

---

20 June 1934

Berlin, Republic of Germany

Ever since his return from meeting Italy's dictator in Venice the week prior, Kurt von Schleicher had felt events gathering around him, like the way air thickens before a thunderstorm. He had risen early on the twentieth, though the ever-faithful Ott had been ready for him even then, and had traveled from the private apartment in the Chancellory to his office. Ott had, as customary, a brief description of his day's agenda, and had even prepared a number of the day's minutiae for immediate signature. Schleicher had dealt with much of this as they had briskly traveled down the twilight-dim corridors, providing a signature where needed. He had even briefly mused that Ott could slip a decree for his own overthrow in the stack, and he would gladly sign it to reduce the day's work a fraction without even reading it. His musings had been interrupted.

Halfway down the high-windowed corridor, the glass had exploded inward violently, showering Chancellor and aide with crystalline shards. Ott, who had been on his left, suddenly lurched and fell against him, and Schleicher ducked backwards behind a pillar, dragging Ott with him. "GUARDS!" he shrieked, his voice not suited to bellowing as Ott's, or even Krupp von Bohlen's, were. The white-gloved Chancellory guard appeared rapidly, scrambling towards him and fumbling with the bolt on his rifle. Schleicher had the chance to look down, seeing Ott's blood soaking both their uniforms. Thank God - that was meant for me, Schleicher thought numbly before returning to the moment. "Ott," he said softly, "don't die on me. I don't know where I would find another aide who can both get things done, and keep his mouth shut." The wounded giant blinked slowly, words slurring out of him, "Sir. Just a flesh wound, sure I'll live." Schleicher instinctively knew this was false, but could not bring himself to argue. They stayed there, pinned behind the pillar as the guards swept the grounds for the sniper, until an ambulance crew came to carry Ott, pale but breathing, away. Once his aide was finally gone, Schleicher resolutely stood, turning toward his office in his bloody uniform, and rapped out for a messenger.

---

---

30 June 1934

Berlin, Republic of Germany

"Eicke," Hauptmann Joseph Dietrich asked his first sergeant for probably the fiftieth time, "why exactly were you not rounded up and put in one of the camps?" He disliked the taciturn, violent noncommissioned officer, but he had proven brutally effective at enforcing discipline in the two or three hundred Nazi turncoats who manned the armored testing company at Meppen.

"Told you before," the Alsatian growled and spat. "Police spy, same as you. Don't judge me, Sepp." The two of them were in the cab of an unmarked truck, the back full of men armed as if for a trench assault - grenades, submachine guns, even a flamethrower. Eicke himself caressed his MP28 in a thoroughly unnatural way - as if he felt more for the SMG than for any living person. Dietrich knew that wasn't strictly true, as he'd met Eicke's wife and children, but Eicke's record in the War spoke for itself. The man was the closest to a monster that Dietrich had ever met, and he'd met Himmler's pet spymaster Heydrich before the Rising.

"All right, you remember the plan, Eicke?"

"Simple as dog shit, Sepp. Surround the building. Break down the door. Anyone says peep, noodle in the head. It all works, then Schleicher makes us heroes. We blow it, the regulars come in behind us and burn us out." Eicke's bleak summary was, Dietrich admitted, accurate enough, so he stopped the truck outside Alois' - the restaurant that Adolf Hitler's brother had founded, which remained a favorite gathering point for the Strasser set. "You got it, Eicke. Let's pull the trigger." As soon as he said the words, he regretted them with a man like Eicke.

Eicke slapped the tarp covering the back of the truck, and troops piled out, quickly and silently surrounding the building. Eicke performed a quick inspection, working bolts and ensuring that every weapon was functioning smoothly and as quietly as possible. As he went down the lines, he murmured to the assembled troopers, "Safeties off, boys. Your fingers are your safeties here on in. Anyone in there does anything stupid, you waste 'em and I'll cover for you. Any of you do anything stupid, I'll have your balls." Dietrich's style was slightly different - a smile, a pat on the shoulder, a brief overview of the plan with each man - but they achieved the same result. Three minutes before nine in the evening, they were ready. A glance at his watch, then Dietrich blew his whistle, loud and shrill, and the men rolled forward into Alois'. Predictably, Eicke was the first one through the door.

"EVERYBODY DOWN, YOU SONS OF BITCHES!" Eicke roared, muzzle high. Despite himself, Dietrich couldn't help admiring him - it was like watching a living American gangster movie. Eicke was Germany's Capone... a thought that he found very unsettling. Even so, tables and chairs scattered as the assembled members of the Social Nationalist leadership desperately sought a patch of floor. Dietrich was in behind Eicke, clearing his throat. "Attention! All of you, by order of the President and Chancellor, are under arrest under suspicion of complicity in the attempted murder of the Chancellor." Men filed in, weapons in one hand and cuffs in the other, and the operation looked like it was rolling smoothly enough.

Looked like - not was.

Out of the corner of his eye, Hauptmann Joseph Dietrich saw two things happen simultaneously. A shape came down the stairs behind the bar, and Theodor Eicke shouldered his submachine gun and fired without hesitation. The MP28 rained casings on Gregor Strasser's head for a second, then the screaming started. A boy of perhaps fourteen was plastered back against the wall on the stairs, slumped at the base, and leaning over him, sobbing inconsolably, was Alois Hitler. Dietrich, whose experience with the Fuehrer had stretched back to November of '23, had met the boy the year prior. His name was Heinrich Hitler... Adolf's nephew. "Eicke," he murmured, barely loud enough for his senior NCO to hear, "What have you done?"

"Serves the dog right," Eicke spat - spittle landing on the back of Strasser's head. "Little bastard's uncle ran away and left us holding the bucket here." Eicke reared back, kicking Strasser viciously in the ribs. "Quit shitting yourselves and GET IN THE TRUCK!" Sepp Dietrich could not help but feel that, despite seizing the SNDAP's leadership, the night had spiraled far out of control. "No reward is worth this," he muttered to himself.

28 February 28 1934

Essen, Republic of Germany

This was not Schleicher's first visit to the Villa Huegel, but it was his first as Chancellor. The vast edifice, built to represent Germany's growing industrial power in the 1870s, was the Krupp family castle, as Schloss Hohenzollern was sacred to Germany's imperial family even in their exile. Nevertheless, it had been built deliberately just out of sight of the great steel foundries, on a landscape kept immaculate even through the lean years from 1929 to now. He had been met at the door by old Gustav's firstborn, Alfried. "Fair warning, the old man is on the attack today," Alfried murmured around his ever-present cigarette, freshly lit from the end of his last. Schleicher gritted his teeth. "I can understand why, Herr Bohlen."

A week prior, Strasser had opened his mouth on the radio. The Vice-Chancellor, stung at his omission from the Kaiser's birthday celebration, had called for the nationalization of all heavy industry, all of the investment banks, and all of the great Junker landholdings, and, even more outrageously, for the reformation of the Nazi paramilitary corps, the 'Sturmabteilung,' in order, as he put it, "to carry the great German revolution to the Judeo-Bolsheviks in Moscow." It was an unapologetically revolutionary program, and Schleicher had been forced to a number of meetings such as this one - he had spent hours in the Truppenamt reassuring Junker officers left and right that their estates were safe while he lived, he had just come from Thyssen's Swiss estate at Lake Lugano, and he expected to spend the rest of the week, possibly longer, personally meeting with Germany's great men, reassuring them regarding the rapidly widening split between the pragmatic Chancellor and his new nemesis.

In the great conference room, Gustav Krupp waited, back to his approaching guest. Krupp emanated polite fury, not bothering just yet to turn to greet Schleicher. "Chancellor," he began without preamble, "what is the meaning of this nationalization nonsense?"

"Herr Krupp, Strasser spoke without consulting me. He does not speak for Germany -"

"Of course he does not speak for Germany. Krupp speaks for Germany. What is good for Krupp is good for the Reich!" Gustav whirled and bellowed. Even Alfried was shocked at this display - to see an old-fashioned diplomat like Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach explode thus was unheard of. To his credit, Schleicher stood his ground. "Just so, Herr Krupp. I agree completely, which is why I, and not an infantry battalion, am in your house. If I stood with Strasser in this, do you think I would be here?"

"Schleicher, we both know that you'd gladly cut your own mother's throat if you thought it'd put you in the President's office." The flat declaration from Krupp was, perhaps, the most blunt, vulgar thing that the old man had ever uttered. "Let us not kid ourselves. I cooperate with you because you disposed of the Reds, and of the Nazis with their Roehm madness. What I cannot understand is how you decided, having rid Germany of that filth, that Gregor Strasser was an acceptable alternative. Even Bruening would have been better."

"As long as we are speaking frankly... Krupp," Schleicher ground out, "Bruening does not believe in the great guns. Those toy cars you have at Meppen? Bruening, God be thanked, does not know of them, because if he did, he would run crying to the disarmament conference. I work with the tools I find at hand. Strasser was the best of a number of bad choices; he split the Nazis and gave us just enough edge to get through last year. I shudder to think of what would have happened without Strasser confusing that Austrian corporal the Nazis call 'Fuehrer.'" Schleicher practically spat the last word.

"And what of this company of thugs you have hidden up at Meppen?" Krupp demanded angrily, cane thumping the tile floor with each syllable.

Schleicher sighed. "Krupp, can we talk about this like sane men rather than gorillas?" He cleared his throat. "I've been living in rail cars for two weeks talking to every rich man who feels Strasser is eyeing his land, his money, or his bank. I even spent an afternoon speaking to the head rabbi of the Berlin synagogue. I have far better ways to spend my time than speaking to a rabbi for an afternoon." Krupp was still bristling, but no longer looked as if he wished to lunge for his throat. "Very well. Alfried! Chairs, please, and join us."

Momentarily, chairs were brought, and the three of them sat, free of observation save for Ott, unobtrusively posted near the door. "You wanted to know about my company of thugs at Meppen," Schleicher said mildly. Krupp nodded sharply, so Schleicher continued. "Most of those men were members of Hitler's organization, as you may have noticed. They have no love of Strasser, which is why I preserve them. However, they, or at least the ringleaders, were more loyal to Germany than the Bavarian corporal." He drummed his fingers on his armrest, eyes gazing at nothing in speculation. "So I preserve them, even offered one of them a position as a tank evaluation officer. That's your Hauptmann Dietrich. Not really our sort, but a good enough soldier, and he does know his way around tanks." He frowned. "Of course, Dietrich's personnel choices sometimes bother even me. His first sergeant... this man Eicke... is the Devil incarnate."

Krupp interrupted his reverie. "Yes, but why are you preserving them?"

"Because if the time comes to deal with Strasser, I need men who already hate him, who are not linked to the Army, and who are not afraid of violence." Schleicher looked directly at Krupp, voice flat, before proceeding. "And, Herr Krupp... I assure you that the question is no longer 'if,' but 'when.'"

---

15 May 1934

Stendal, Republic of Germany

Peter Volkmann awoke with a groan as the bugle went off. He had reported to Stendal once more as soon as his clases were complete for a summer's worth of military training. He was not, as he had thought, something special for his pilot's qualifications; he was, rather, as the platoon sergeant had gleefully informed him, scum, for wanting a commission. Until he had shown he was something other than a creature unfit to crawl through the muck of the Earth, he was a cadet, not even marked as a proper non-commissioned officer because of his special ranks.

The thirty officer candidates of his training platoon roused themselves; after a week of this, they were thoroughly trained to get out of their racks before the rack, and their world, collapsed under Feldwebel Koller's blows. Peter had expected, with his technical background and completed private pilot's license, to be something special here. In both cases, he was disappointed. To his right was a pilot... or so he claimed... whose stories of aerial derring-do generally seemed to end with "And anyway, the crate broke up on landing. Hell of a way to spend the weekend." How Cadet Galland had managed to survive this long was a mystery - he had broken up his second aircraft on landing just a month prior, and it was still unclear how he had persuaded Lufthansa that they should put him on leave for this course. It was Galland, rather than Volkmann, who had quickly developed a reputation as the standout, for Galland had logged far more hours in the air than anyone else here, and "Dolfo" Galland was studiously unimpressed by the platoon sergeant, the company commander, or indeed the only man with a car on post, now-Major von Richtofen.

Galland ostentatiously rubbed his eyes, yawning loudly. "Christ on a bicycle, Koller," he drawled, "how the hell do you expect us to fly on four hours of sleep?" Koller pounced, almost punching Galland instinctively. "Shut up, Galland. I hear another word out of you today, it'll be your last. Understand?" Galland responded with a very loud "Mmmmmmrph," lips prominently closed. Koller, frustrated by the letter-of-the-law obedience to orders, was forced to content himself with stalking away.

Volkmann muttered across to Galland, "Jesus, Dolfo, you're going to get yourself killed before graduation."

"Don't be crazy, Petie. I've been flying for four years, I've got more'n a hundred hours... even Koller's not stupid enough to kill a pilot who knows what he's doing." Volkmann envied the younger man - Galland was fifteen months younger than he was - who had gone straight from gymnasium to Lufthansa pilot's school. The cadets spent the rest of the morning in silence, punctuated by Koller's abuse, calisthenics, and, far too late, breakfast. They had, of course, arrived with only five minutes remaining before the mess closed; as a result, they had only minutes to ram down their too-small breakfast before continuing on with training. "Training," as it turned out, consisted very little of aerial warfare, and a lot more of marching, crawling, gas drills... anything, in short, to get them adjusted to life in uniform without spending expensive aviation fuel. At the end of it, as at the end of every "day" - they ended before midnight, but only by seconds - he passed out, exhausted, but with a shined pair of puttees under his bunk and the cleanest of his field uniforms hanging from the end.

It was a six-week camp, after which they graduated to the coveted status of "Under-Officers," signalling their transition into the commissioning program. It was, by Stendal's limited scope, a splendid occasion, with a small band, the first appearance of the cadets in their blue uniforms, and the issue of an officer candidate's dagger to each man. At the culmination of the ceremony, a flight of twin-engine Dornier 'mail planes' roared in low over the field, causing the unwary to lose their headgear. At the end of the camp, Major von Richtofen sat down with each of them for a few minutes for a brief interview, including a record of the new officer candidate's choice of assignment. "Dolfo" Galland had made his choice quite clear - the candidates in the hallway had heard him exclaiming, "Fighters, damn it, where the action is!" even before his interview had properly commenced.

When Volkmann got his turn, Richtofen was rubbing his forehead, frowning. This was, Volkmann thought, one disadvantage of a name at the end of the alphabet. "Volkmann. Peter, isn't it? Sit down," Richtofen said absently, opening Peter's file.

"So, Unteroffizier Volkmann. First off - congratulations." Richtofen offered a genuinely warm smile and a handshake, just as he had the day Peter had soloed. "Seems like you spend a lot of time here, time to get you a proper duty assignment. You have any preferences?"

"Well, sir... what are my choices?"

"Since you're rated as a pilot, fighters and bombers, really. Fighters are likely to get all the glory, but no one is going to win a war with fighters. We can lose one without them, but we'll never win one with them." Richtofen tapped his pen on the desk thoughtfully before continuing. "There are two types of bombers... dive bombers, which, frankly, are pilot-killers, and level bombers, like the new Dornier you got to see earlier. Personally, I think the Dornier is the weapon of the future. Your friend Galland," Richtofen noted with a quirk of his mouth, "disagrees vehemently."

"If it's all the same, sir... I'll stick with Dolfo." Volkmann shifted, uncomfortable with even the hint of disagreement with Richtofen, who, in addition to his name, was much more likeable than most officers of his age. Richtofen reminded him of his father; they were both engineers by training, they were of similar age, and only background and lineage had really separated their fates. Richtofen sighed, shook his head, and made a note in the file. "The fighter course it is... from here, you're going to Doeberitz to complete your flight training. You'll be traveling with Unteroffizier Galland, you'll be happy to know." Richtofen straightened up, continuing the interview. "Now... how're your studies going? Colonel Student asked. You'll be happy to know he remembered you... he's back from Russia, along with everyone else."

"Oh, they're going very well, thank you. I'm in General Becker's explosives chemistry class for next semester, and he has offered me a position as grader for the fall introductory ballistics course. It doesn't pay much, but I understand it covers my cadet stipend." He looked faintly embarrassed talking about money, but Richtofen grinned. "Good for you. I damn near broke myself, and that as on an embassy budget, back in Italy in '30. Volkmann... may I ask you a question?" Volkmann blinked, not expecting this level of familiarity from the most remote figure on base. "Certainly, sir."

"Why'd you choose to be a pilot, especially for us? I mean, you could've gone and worked for... oh, I don't know, Henschel has a big plant they're putting up on the other side of Berlin." Richtofen leaned across his desk, awaiting Peter's answer. Peter shrugged diffidently. "I don't know. Colonel Student made a big impression, I guess. Talked about his War experience, told me that the air was where it'd all be figured out next war. That, and it seemed like where I could use what General Becker was teaching. It's all geometry and physics in the air, not like on the ground." Richtofen shook his head, leaning back. "All wrong, Volkmann. In the air, you fight by instinct, not scientifically. Never mind what Boelcke nailed to his office door, the big rule is bring your crate home."

They continued in a surprisingly informal interview for several minutes before Richtofen looked up at the clock. "Behind schedule, Peter. Better grab your gear and get out before Koller locks up the barracks. He has this week off, you know..."

At that moment, Koller himself, as if a genie, burst into the small, stuffy office, barely remembering to salute. "Sir! There's been an attempt on the Chancellor!"

---

20 June 1934

Berlin, Republic of Germany

Ever since his return from meeting Italy's dictator in Venice the week prior, Kurt von Schleicher had felt events gathering around him, like the way air thickens before a thunderstorm. He had risen early on the twentieth, though the ever-faithful Ott had been ready for him even then, and had traveled from the private apartment in the Chancellory to his office. Ott had, as customary, a brief description of his day's agenda, and had even prepared a number of the day's minutiae for immediate signature. Schleicher had dealt with much of this as they had briskly traveled down the twilight-dim corridors, providing a signature where needed. He had even briefly mused that Ott could slip a decree for his own overthrow in the stack, and he would gladly sign it to reduce the day's work a fraction without even reading it. His musings had been interrupted.

Halfway down the high-windowed corridor, the glass had exploded inward violently, showering Chancellor and aide with crystalline shards. Ott, who had been on his left, suddenly lurched and fell against him, and Schleicher ducked backwards behind a pillar, dragging Ott with him. "GUARDS!" he shrieked, his voice not suited to bellowing as Ott's, or even Krupp von Bohlen's, were. The white-gloved Chancellory guard appeared rapidly, scrambling towards him and fumbling with the bolt on his rifle. Schleicher had the chance to look down, seeing Ott's blood soaking both their uniforms. Thank God - that was meant for me, Schleicher thought numbly before returning to the moment. "Ott," he said softly, "don't die on me. I don't know where I would find another aide who can both get things done, and keep his mouth shut." The wounded giant blinked slowly, words slurring out of him, "Sir. Just a flesh wound, sure I'll live." Schleicher instinctively knew this was false, but could not bring himself to argue. They stayed there, pinned behind the pillar as the guards swept the grounds for the sniper, until an ambulance crew came to carry Ott, pale but breathing, away. Once his aide was finally gone, Schleicher resolutely stood, turning toward his office in his bloody uniform, and rapped out for a messenger.

---

Good evening, America, this is William Shirer reporting from Berlin for the Universal News Service. German Chancellor General Kurt von Schleicher was the target of an apparent assassin this morning during his walk to work. While the Chancellor was unharmed, his aide is currently hospitalized in grave condition. The Chancellor proclaimed a state of martial law in the city of Berlin, to last seventy-two hours while the assassin is tracked down. No word from the Berlin police on how the search is proceeding, but there has been a very heavy police presence in the city since the beginning of last year, and informed sources at the United States embassy indicate that they expect the police presence to become heavier.

General von Schleicher has a wide variety of enemies because of his suppression of the Communist and National Socialist revolts last year, and the attached emergency decrees which led to the temporary suppression of the Social Democrat Party. However, Heinrich Bruening, the Catholic Center Party leader, who has been imprisoned in the fortress at Landsberg for the past six months pending a decision regarding his party's fate, released a statement to the press this afternoon, calling the assassination attempt a "cowardly, despicable act" and pledging his support to Schleicher in the country's moment of crisis. "The Chancellor and I have collaborated before, and though we have disagreed recently, we are united in our support for Germany," Bruening's statement reads in part.

As you may expect, the situation is very fluid here, and the Chancellor's office has released very little information thus far. We will have more information for you as the situation here in Berlin develops. This is William Shirer in Berlin for the Universal News Service, signing off.

---

30 June 1934

Berlin, Republic of Germany

"Eicke," Hauptmann Joseph Dietrich asked his first sergeant for probably the fiftieth time, "why exactly were you not rounded up and put in one of the camps?" He disliked the taciturn, violent noncommissioned officer, but he had proven brutally effective at enforcing discipline in the two or three hundred Nazi turncoats who manned the armored testing company at Meppen.

"Told you before," the Alsatian growled and spat. "Police spy, same as you. Don't judge me, Sepp." The two of them were in the cab of an unmarked truck, the back full of men armed as if for a trench assault - grenades, submachine guns, even a flamethrower. Eicke himself caressed his MP28 in a thoroughly unnatural way - as if he felt more for the SMG than for any living person. Dietrich knew that wasn't strictly true, as he'd met Eicke's wife and children, but Eicke's record in the War spoke for itself. The man was the closest to a monster that Dietrich had ever met, and he'd met Himmler's pet spymaster Heydrich before the Rising.

"All right, you remember the plan, Eicke?"

"Simple as dog shit, Sepp. Surround the building. Break down the door. Anyone says peep, noodle in the head. It all works, then Schleicher makes us heroes. We blow it, the regulars come in behind us and burn us out." Eicke's bleak summary was, Dietrich admitted, accurate enough, so he stopped the truck outside Alois' - the restaurant that Adolf Hitler's brother had founded, which remained a favorite gathering point for the Strasser set. "You got it, Eicke. Let's pull the trigger." As soon as he said the words, he regretted them with a man like Eicke.

Eicke slapped the tarp covering the back of the truck, and troops piled out, quickly and silently surrounding the building. Eicke performed a quick inspection, working bolts and ensuring that every weapon was functioning smoothly and as quietly as possible. As he went down the lines, he murmured to the assembled troopers, "Safeties off, boys. Your fingers are your safeties here on in. Anyone in there does anything stupid, you waste 'em and I'll cover for you. Any of you do anything stupid, I'll have your balls." Dietrich's style was slightly different - a smile, a pat on the shoulder, a brief overview of the plan with each man - but they achieved the same result. Three minutes before nine in the evening, they were ready. A glance at his watch, then Dietrich blew his whistle, loud and shrill, and the men rolled forward into Alois'. Predictably, Eicke was the first one through the door.

"EVERYBODY DOWN, YOU SONS OF BITCHES!" Eicke roared, muzzle high. Despite himself, Dietrich couldn't help admiring him - it was like watching a living American gangster movie. Eicke was Germany's Capone... a thought that he found very unsettling. Even so, tables and chairs scattered as the assembled members of the Social Nationalist leadership desperately sought a patch of floor. Dietrich was in behind Eicke, clearing his throat. "Attention! All of you, by order of the President and Chancellor, are under arrest under suspicion of complicity in the attempted murder of the Chancellor." Men filed in, weapons in one hand and cuffs in the other, and the operation looked like it was rolling smoothly enough.

Looked like - not was.

Out of the corner of his eye, Hauptmann Joseph Dietrich saw two things happen simultaneously. A shape came down the stairs behind the bar, and Theodor Eicke shouldered his submachine gun and fired without hesitation. The MP28 rained casings on Gregor Strasser's head for a second, then the screaming started. A boy of perhaps fourteen was plastered back against the wall on the stairs, slumped at the base, and leaning over him, sobbing inconsolably, was Alois Hitler. Dietrich, whose experience with the Fuehrer had stretched back to November of '23, had met the boy the year prior. His name was Heinrich Hitler... Adolf's nephew. "Eicke," he murmured, barely loud enough for his senior NCO to hear, "What have you done?"

"Serves the dog right," Eicke spat - spittle landing on the back of Strasser's head. "Little bastard's uncle ran away and left us holding the bucket here." Eicke reared back, kicking Strasser viciously in the ribs. "Quit shitting yourselves and GET IN THE TRUCK!" Sepp Dietrich could not help but feel that, despite seizing the SNDAP's leadership, the night had spiraled far out of control. "No reward is worth this," he muttered to himself.

Last edited:

No problem, and I've also answered "Why Student, why not someone else, like Galland?"

And no, this does not mean that Peter Volkmann is going to be a famous fighter ace. Events in Galland's own personal future see to that.

And no, this does not mean that Peter Volkmann is going to be a famous fighter ace. Events in Galland's own personal future see to that.

I would have put him into Bombers to be honest, as I like to say, Fighters were far too obvious, and anyway I am still rooting for him becoming a Para.

7. The End of an Era

20 August 1934

Tannenberg Memorial, Republic of Germany

The old man was dead. Just as Schleicher had ended the Crisis, President Hindenburg had precipitated another by his demise. It was hardly a surprise - he was eighty-four, and the past year had seen a dramatic decline in his mental health. Hindenburg's personal testament had specified a small funeral, but after the instability of the last year and a half, Germany needed spectacle to distract the few citizens who had not accepted the measures Schleicher had taken to preserve the Republic.

Schleicher had achieved most of his goals in the Reichstag following the "knife fight" and Strasser's imprisonment. The Strasser Trials were swift and decisive - Bruening had been released and the SPD reinstated as a gesture of conciliation toward the center parties, Thaelmann expelled to the Soviet Union with the Reichstag conspirators, Van der Lubbe executed as a spy and saboteur, and Roehm and Strasser both condemned to death for treason. They had been executed by firing squad a week after the raid on Alois'. The same legislation which had restored the SPD had permanently suppressed the Nazi and Communist wings. Schleicher had promulgated all of the laws that the Conservatives wanted - protection of property (except in case of criminal confiscation), protection of the great estates (except in case of fraud or corruption), protection of the banks (except in case of insolvency)... everything which they had wanted, with enough loopholes to ensure that a strong man could still get the business of government done.

Germany was now stable enough that he had reached an agreement with the Reichstag leadership within days of Hindenburg's death. He would exercise the powers of the President, but not hold the office, until the end of September, by which time a presidential election would be completed. In the meantime, there were two matters to be dealt with - first, ignoring the President's private testament and giving him a very public memorial service. The second matter - Hindenburg's political testament - he did not wish to make public just yet.

He surveyed the assembled guests at the Tannenberg Memorial, then nodded to the bandmaster, who struck up Chopin's Funeral March. The funeral procession moved slowly forward. Seeckt, from the reviewing stand, watched the President's son, Oskar, act as the lead pallbearer, though the actual bronze coffin was supported by a caisson, too heavy to be borne by the men in the role. The pallbearers had been carefully chosen - Bruening, Papen, and even old Ludendorff were down there, paying tribute to a man that they all had reservations about up until this very moment. Schleicher's mouth quirked - they had all supported Hindenburg in life, where he overshadowed them, and now, in death, they supported him still, though if the caisson tipped even slightly, the massive bronze coffin would crush them.

He himself was on the reviewing stand as evidence of Germany's continuity - the President is dead, long live the President, he thought, raising his hand in salute as Hindenburg passed. Behind him, the ever-loyal Ott, arm tightly bound to reduce risk of aggravating his wound, was the only person who remained seated, his injuries excusing him from rising as the dead President approached his memorial. The flag dipped, lowered, stayed at half-mast, and Schleicher gave a tiny nod. The transfer of coffin to mausoleum began, and Schleicher's mind drifted to the west.

To Doorn.

---

Doorn, Kingdom of the Netherlands

Paul Hausser had last seen the man in front of him in 1918, during a Berlin parade. Wilhelm II, Emperor of Germany, straightened from his rose bush, turning to face the assembled officer. He looked more like an elderly, well-meaning grandfather than the rightful master of the nation that once dominated Europe; Hausser found himself unable to fnd anything to say to this man. Fortunately, the man who led their delegation was much more familiar with Wilhelm and especially his son. "All-Highest," Fedor von Bock began, "I bear word from Berlin."

"Oh?" Wilhelm asked, eyebrows rising. "Always good to hear from Berlin. I heard that poor old Paul was dead. Poor man, having to deal with the democrats all these years. Even I never had to deal with them." Bock waited through Wilhelm's musings, nodding his head ever so slightly. "Just so, All-Highest. The Chancellor sends his greetings and asks that you consider him at your disposal." The resemblance to an avuncular old man vanished, the eyes sharpening. "Then it is time for Our return?"

"No, All-Highest."

"No, General? Then he is hardly at my disposal."

"All-Highest... the Chancellor has an obligation to the Constitution of the Republic, much as he finds it repugnant." That much was true; it did not, however, explain why Schleicher, who both Hausser and Bock knew was only as trustworthy as any individual was useful to him, had not asked for Wilhelm's return. "Instead, he has a suggestion which he believes will meet both your approval and the needs of the constitution." The old man pursed his lips, nodding. "Go on, General. I remember you gave good advice in the old days." He smiled thinly. "Unlike some I could name, were I not a gentleman."

"All-Highest, the Chancellor believes that the Kronprinz should run against Bruening." It hung in the air between them, Wilhelm's eyes staring into the distance. "I see... so I am not to be restored to my rightful place, and my son is to take his laurels from the hands of the democrats."

Bock looked pained. "All-Highest, it is better surely than living in needless exile!"

"Yes, and what happens when the democrats change their minds, and a year or two later demand another 'president?'" Wilhelm emphatically slapped his gloves against his thigh. Hausser spoke now.

"All-Highest. I have spoken with Chancellor Schleicher myself on other matters. He desires stability for Germany, I am convinced, and he has seen that democracy and stability are incompatible." Hausser hesitated before making a declaration that he believed, but had no way of supporting. "I believe, All-Highest, that the Chancellor means to find a constitutional way for your return." Wilhelm looked Hausser directly in the eye, measuring him. "So you say. Would you trust Chancellor Schleicher, General?"

"If we wish to see you, or your sons, on the throne of the Reich, I do not believe we have a choice, All-Highest."

Wilhelm nodded slowly. "Very well then. For my sons. For myself," he added, bitterly, "nothing."

---

23 August 1934

Berlin, Republic of Germany

Schleicher was in his usual place, behind his desk dealing with the admittedly reduced volume of work that a properly functioning Reichstag created, when Ott stuck his head through the door. "Chancellor, your appointment is here." He looked across his desk, setting his old Pickelhaube on the corner of his desk. "Excellent, Ott. Send him in."

His visitor was the perfect modern aristocrat - witty, charming, and well-connected. Unfortunately, Schleicher had discovered to his chagrin two years prior, there was very little else to Franz von Papen. Papen was a professional dilettante, had even played at being a spy while assigned as a diplomat in America during the War. Only his service as Chancellor, in fact, had cleared the charge from his name - a gesture of goodwill on the Americans' part. Papen's moustache was, as usual, immaculate, and he had cultivated a certin air of cunning, but it was, as Schleicher knew, a show and nothing but.

"Franz," Schleicher beamed. The two had long been friends; it had only been when Papen was appointed to power that his shortcomings had become glaringly obvious. "Kurt," Papen said, somewhat guardedly, Schleicher's destruction of his Chancellory not completely forgotten or forgiven. "Sit, sit, Franz. Ott?" he demanded, depressing the intercom switch on his desk. "Send in tea for Franz, and let me know when Oskar gets here."

"Oskar and tea, Kurt?" Papen smiled in appreciation. It'll be like Potsdam Guards all over again. Must be important." Schleicher nodded emphatically. "It is... and there's tea... and Oskar!" He waved to the other chair as Oskar von Hindenburg arrived, looking as confused at Schleicher's conviviality as Papen had been. The old president's son took a chair as Papen took the tea, Schleicher smiling across at both of them.

"Now, I'll get right to the point." He cleared his throat, hand resting on the helmet on his desk. "Franz, Bruening's going to run as the Center candidate. It's already in the papers. That doesn't leave a lot of room for you. What I want you to do... you two together. I want you to establish a new party... the Reichspartei? Is that an acceptable name? Your goal will be to get the Kronprinz elected." Two jaws dropped; Schleicher held up his hand. "Let me explain. I will be working in the Reichstag to prepare a piece of legislation to return Germany to its proper state. Be done with this Republic nonsense, get things back to the way they should have been."