Kurt_Steiner: Sorry, if I told you, I'd ruin all the suspense.

yourworstnightm

yourworstnightm: It's sporting to let someone score a few points in a game before utterly crushing them, don't you agree?

Viden

Viden: So is the United States the Fourth Rome?

Nathan Madien: Thanks for the catch.

-----

America at War - Part III

With the first month of combat in the war having proven indecisive, matters began to unfold rapidly in Cuba and Mexico. After a week-long lull in the fighting, II. Army launched itself across the Rio Grande on June 2 before the Mexican army could dig-in following its victory over Wedemeyer. I. Corps under Eisenhower and III. Corps under Millikin crossed over the border, supported by the rest of II. Army and the bulk of the Army Air Corps. After rapidly ceasing Nuevo Laredo and Reynosa, the American attack pushed south toward Monterrey. Two Mexican divisions stood in the way, giving their ground only after a day of heavy fighting.

Back to the west, a half-hearted Mexican attempt to relieve Cardenas' trapped army was beaten back by MacArthur with ease on the 5th. Unwilling to waste his army in a pursuit of Cardenas' forces down the desolate peninsula, MacArthur instead detached the DeWitt, believing that the American cavalry, backed by the guns of the Pacific Fleet, would be more than a match for whatever resistance Cardenas' slowly-starving soldiers could mount. On the 6th, an entire division surrendered at Rosarito, apparently having run out of ammunition in the hasty retreat from Mexicali.

DeWitt continued to pursue Cardenas' army before encountering the bulk of his forces at Santa Rosalia on June 11. Fully-supplied and aided by the guns of the battleships and heavy cruisers, DeWitt routed General Villasina's men and forced the Mexican general to surrender after a brief but intense battle.

Back at the northern end of the peninsula, MacArthur finally began his push from Mexicali southward along the eastern coast of the Gulf of California. With Lt. General Krueger's III. Corps screening his left flank, MacArthuer advanced steadily on Hermosillo. Though outnumbered, the Mexican defenders held up IV. Army's advance for nearly two days before the weight of the American attack forced them to retreat.

The news of MacArthur's most recent victory was soured, however, when reports arrived from New Mexico. Having deemed that region too desolate and remote to warrant more than a token defense, MacArthur had allowed the New Mexican border to remain largely undefended. Seeing this as an opportunity to score a propaganda victory, the Mexican general staff ordered an invasion. A pair of Mexican divisions crossed the border and pushed several hundred miles into the interior before anyone had noticed. Though embarrassing, the invasion was strategically insignificant. MacArthur testily declared to reporters, 'Let them run around the desert all they want. I'm winning a war here.'

In any case, the invasion of New Mexico did not provoke Roosevelt to redirect the Army's thinly-stretched assets from elsewhere. Instead, the Americans followed up on their push across the Rio Grande; having finally secured Monterrey and Saltillo, the rest of II. Army crossed the border, seizing Matamoros in a brief but vicious street battle. Already struggling to contain Eisenhower, the Mexican army could muster only a single understrength division to contest Stillwell's main thrust. the retreat was called after only a few short hours of sporadic fighting, leaving the whole of the state of Tamaulipas open to the American army.

Compared to the war in Mexico, events in Cuban took a bizarre twist that left American intelligence experts baffled. Although successful in recapturing Guantanamo Bay, I. Army had failed to break out, forcing the rest of I. Army to retire back to Miami. Having recouped its losses, I. Army was given a golden opportunity. After the initial landings, Cuban forces had been diverted south to aid in the containment effort, leaving much of the coastal defenses either undermanned or neglected entirely. On June 4, the remainder of I. Army came ashore at Nuevitas and rapidly advanced into the interior of the island, seizing the city of Camaguey unopposed.

The most recent intelligence reports suggested that only a single Cuban division, under Mj. General del Castillo, had been trapped as a result of the landings. Leaving Lt. General Bradley to protect Camaguey, Hodges pressed eastward across the island along a wide front, while Clark finally broke out of Guantanamo Bay, forcing del Castillo to surrender. As Clark moved up the island to link up with the rest of I. Army, the Americans stumbled across one Cuban division after another. Two divisions were discovered on the 9th, another on the 13th, and yet another on the 16th. Though none of these discoveries hindered Clark's advance for more than a few hours, the fact that four Cuban divisions had appeared out of thin air baffled intelligence experts. Regardless, the President was more than happy to report to the American public that over half the Cuban army had been eliminated in just a few short weeks.

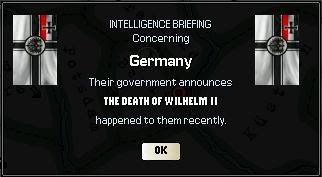

But it was Europe where momentous events were unfolding, and it was where Roosevelt's attention was most frequently directed; the fate of Europe hung in the balance with the outcome of the war between France and Germany. After the liberation of Alsace-Lorraine and succesfully crossing the Rhine at Freiburg in late April, the situation had largely stalemated, though the German army managed to retake the city in early May. The declaration of war had diverted media attention firmly back to the United States, and the European war was largely neglected, until news arrived from Berlin on June 5. After having ruled the German Empire for almost 53 years, Kaiser Wilhelm II Hohenzollern died at the age of 82.

Wilhelm II died at Potsdam in his sleep.

The news Wilhelm's death shook the entire nation; under him, the German nation had risen to the status of superpower, had endured the Great War, and become the preeminent state of the European continent. Having been the ruler of German for the entirety of most citizens' entire lives, the Kaiser's death could not be but looked upon as the passing of an age in both German and world history. Whether events on the front presaged this view of his death, or if his death precipitated those events, one can only speculate. The coronation of the Kaiser's son, Wilhelm III, was to be a true display of imperial pomp at the New Palace in Potsdam, but the military-minded Crown Prince chose to do away with such extravagance. On June 12, Wilhelm III became Kaiser of the German Empire in a small and spartan ceremony.

The Crown Prince's decision reflected on his mentality, but also on the condition of the empire. Questions had been raised as to whether or not the lavish coronation originally planned could even have been afforded. Indeed, in early June, Marshal Manouchian succeeded in breaking through the German lines in the Rhineland. First, Luxembourg fell. After Wilhelm II's death, the French continued to advance deeper into Germany, sweeping through the Saar and reaching the confluence of the Rhine and Main, threatening Mannheim, Heidelberg, Frankfurt, and even Cologne by the 14th.

Not prone to panic in the face of such major setbacks, the Germans counterattacked, with von Leeb successfully retaking Luxembourg and threatening to encircle the French forces in the Rhineland while von Reichenau held the French advance in the south. But the French continued to press at the German lines in other sectors, finally crossing the Meuse south of Liege and capturing the city of Arlon on the 16th. Within another week, Liege had fallen and the whole of German Belgium was under French occupation, in turn threatening to encircle von Leeb in Luxembourg. As before, the German Army was bruised yet continued to fight as doggedly as ever.

The French gains in June, 1941.