Splendid! Can't wait to see what happens here. Maybe history will bring Britain and France to blows once more. Brothers of the faith does not necessarily mean brothers in arms, and the Pretender (as he may become in the future) will surely want to keep his throne...

Paris ne vaut pas une messe! - A Huguenot IN AAR

- Thread starter Milites

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Thanks everybody. The update is coming along nicely. Maybe sometime tomorrow it'll be done. It's a joy writing on ymnew Mac keyboard

To Kurt:

1) No

2) Partially correct

3) Indeed!

4) Also true, but with a twist

To Kurt:

1) No

2) Partially correct

3) Indeed!

4) Also true, but with a twist

Maps:

1) Japan, you played MM, hinted at a possibility of an aar, and now teasing us with this publicity stunt.

2) Autonomous estates? Lands given to royal family members?

4) ...the twist? Spanish Civil War?

Glad you're back!

1) Japan, you played MM, hinted at a possibility of an aar, and now teasing us with this publicity stunt.

2) Autonomous estates? Lands given to royal family members?

4) ...the twist? Spanish Civil War?

Glad you're back!

Part IV

By the turn of the sixth decade of the 17th century one could be tempted to describe the geo-political situation on the European continent as a rather one sided affair - almost unilateral as some have gone on to write. Given the fact how French, Huguenot and Absolutionist armed forces, backed by a diplomatic corps of enormous élan, held the majority of central Europe, and its heartland, centred on the German Empire, firmly under the influence of the Louvre.

Yet the defining point of this era is not the temporary hegemony of one royal house and its precise religious practices. It is in turn, however, the paradox of the age that has attracted scholars – the paradox that even as the French lilies blossomed to their final glorious summer over the fields of old Europe, their time was coming to a rapid close.

The reason for this lay not with Habsburgs, Spaniards or Papists, but rather with the absolute success with which the Bourbons had stamped the leather-clad boots of their immense armies from the currents of the Ebro to the dark waters of the Danube. Across the channel in England and in the flat, tulip-covered Netherlands the changing rulers had, beforehand, always followed Paris’ lead when it came to the tending of the Protestant cause and the advancement of the Reformation.

Now, being sick with having become taken for granted by the rigorous Huguenot foreign department, the Dutch and the English and the Scots had all found the international situation with French arrogance unbearable. Strangled by its own achievements in the field and at the negotiation tables, the same Protestant Alliance that had arisen from the nascence of the armed conflict surrounding the wars between the Christian churches had now, seemingly, extinguished itself.

A battalion of French troops advances through a snow-covered landscape in the vicinity near the Netherlands whilst several companies to their rear are being prepared for deployment.

In The Hague a young and ambitious Prince of Orange had no intentions of being reduced to a loyal French satrap with a minor dependency whilst his neighbours where chained around him with iron forged in the mines of the Rhine valley and in the countryside of the British isles, peer and serf alike were fearing the Huguenot influence which James II Stuart seemed to revel so much in. Two thirds of the Protestant alliance were thus also caught in the paradox of the time. On one hand they were in numerically majority against France (two to one), but on the other they were very much in minority (France had gained far the most by the Religious Wars) – French wilful and condescending behaviour towards the English and Dutch allies had assured that.

On the great isles across the Channel, the commoners did not have the same physical ‘threat’ of the Huguenot Armées hanging over their heads, but they did enjoy having a sovereign who delighted his court by French plays, French cuisine, French services and French advisers. In this aspect the Dutch were fortunate with their increasingly Francophobic William of Orange. However, it wasn’t only the English and Scottish who were alarmed by the inconsistency of London’s reverence for Paris and its disdain for the disgruntled native aristocracy.

Dublin Castle also feared the implications an increasingly pro-French Stuart government could have on the fragile peace that had descended on the waters of the Irish Sea. Despite being exceptionally delighted and proud of their victory over the Absolutists in the War of 1657 where Oliver Cromwell and Charles Fleetwood had destroyed a Huguenot field army, the Parliamentarian strategists still shivered when they thought of a Royalist navy transporting French troops en masse to the shores of Ireland – an outcome all too easy to imagine for Dublin’s liking.

However, replacing James, who had surprisingly skilfully secured his inheritance at his father’s death, seemed downright impossible for the Parliamentarians who were still dealing with the troubles surrounding Oliver Cromwell’s passing years before. With the second son of Cromwell dead it rested upon the fourth of the late lieutenant general’s sons, Henry, to lead an uneasy coalition between himself, the skilled – albeit ageing - Charles Fleetwood and the immensely popular John Lambert. The native Irish royalty which was kept alive as a symbolic figureheads with which the Parliamentarians hoped to quell Irish resistance had no relevance for what the exiles thought of as a solely English matter of succession – therefore they had to look abroad for a substitute…

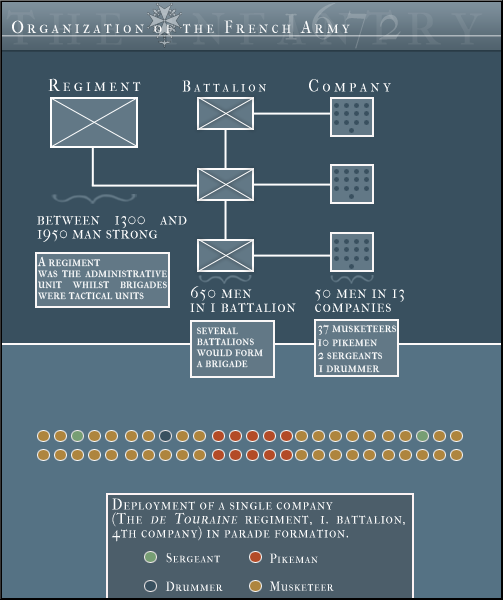

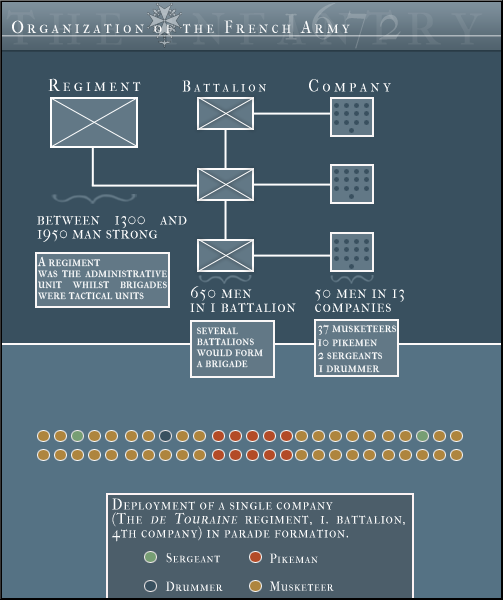

Organisation of the French infantry in 1672.

***

“Look to the North”

D’Artagnan jerked the reins backwards with his gauntleted hands and drove his freezing mount into a brutal stop on the gravel road, his exited breath visible in the morning cold as small clouds of smoke. It had been a long and harsh ride and all three were tired and battered. As the Comte gazed across the lead coloured waves and the grey foam of the icy Channel, he could feel a certain sense of dread and sensation beginning to work its way up his throat.

“Feuquiéres, hand me your telescope… act smartly for God’s sake!” The nearest of the two other musketeers lead his sweating horse to the Captain’s side and after a quick search in his ruck-sack hanging from the horse’s saddle produced the object which the Comte unfolded with nervous clumsiness.

Streaming out from far away, over the olive coloured and frost covered hills a line of ships were passing out to sea, their heavy oaken bulks breaking the waves before them. The foremost of the vessels slowly turned starbow revealing to the Comte an eerie row of long barrelled cannons protruding from her darkened battery hatches. Suddenly in the tallest mast a flag went up and it unfolded as the icy western wind caught it, making the standard flutter wildly – as if it by this design attempted to discharge itself from the mast which held it in captivity. In the morning light it became clear to the three spectators. Upon its maiden white linen a scarlet cross was wrought and beside it a lion rampant, holding in its claws a raised sword above its crowned head, was embodied – dancing on the fluttering cloth.

“The heraldry of the Dutch house alongside the colours of England’s parliament,” D’Artagnan exclaimed before finishing with a smirk “they must be on their way already. William certainly wastes no time.”

“With such an escadre the Dutch will be able to land and supply at least half a dozen battalions. Why would they do that? Where are they going, monsieur Capitaine?” enquired Catinat.

“I fear that they might wish to raise objections to James’ succession to the English throne… In a rather violent sort of way.” Both the young musketeers looked at him in disbelief. France, England and the United Provinces had been allies for generations. Families had arisen and had been extinguished in the slaughtering of the scores of wars all over the world which the Protestant powers had pursued in unity against the Catholic repression. Conflict between them would be akin to civil war…

The ships moved faster and faster as the wind caught hold of their bulging sails. Soon they would pass the curve of Pas de Calais and the guns of alert French forts. Would they pass unharmed? Would the Louvre order the batteries to fire on allies acting in enemy interests?

With the sea on their right side, the three riders made way from the road and down a small hill side covered in frozen weeds. Feuquiéres whistled a royalist air eerily, which was heard often in his company, as he guided his mount down the tricky path. When a short jump from his steed brought him in front, he turned around in his saddle and looked thoughtfully at the Comte.

“What to do now, monsieur? The Dutch are at sea, the Flemish behind the dunes are probably not going to enjoy a surprise visit from the three of us and Calais is all to far away so no fresh horses… God, I miss Germany.”

“…You miss being in a warm salon with pleasant company, is what you miss you lazy Papist. Stop your confession before you make us all believe in the heresy of saints!” Catinat interjected from the rear – adding extra emphasis by throwing the last of his rations – a dusty piece of crust – after Feuquiéres. D’Artagnan chuckled at his companions’ bickering, but couldn’t help feeling that after all, Feuquiéres might have figured it out alright.

The Comte D’Artagnan, captain of the first company of the King’s Musketeers, was one of the few veterans left in the Huguenot army who had fought with the Vicomte all the way since before his great victories.

As they followed the road below, the Comte suddenly felt uneasy once more. After a turn of the road he understood why.

The way was blocked by two large trunks of dead, rotten wood and behind it stood at least half a company’s worth of armed men covered under heavy cloaks and coats, their faces shielded from the damp cold by broad hats of filter. Their leader, a man of small statute and golden moustache, armed with a partisan raised himself upon the barricade and shouted in a coarse language that penetrated the silence of the scenery like bullets of lead through virgin flesh.

“Halt! in de naam van Oranje. Wie gaat er?”

Perplexed, Catinat brought his mount up on the sides of the two others so that the three musketeers now were lined up against the defenders with the Comte D’Artagnan in the middle. It was now he who now took it upon himself to answer.

“Nous sommes mousquetaries du roi et de la France, monsieur!...”

A mumble resounded throughout the ranks of the Dutch infantry, for that was the language they spoke the Captain noted, as the message was first translated and then debated amongst them. A bugle called somewhere within the moving forest of pikes and the colours in its midst shook in response to a energic drum roll. D’Artagnan could all too well imagine the pair of wooden sticks dancing on the drumhead as he had seen them do before on the fields of Bohemia and Germany whilst soldiers were deployed and entire sectors of troops moved to the whims of a marshal’s baton. Something lead him to the thought that his answer might not have been approproate...

With some difficulty another man climbed the interimistic ramparts. Clad in a bottlekneck green overcoat with a yellow silk scarf around his waist, he planted one dark brown jackboot in front of the other and announced to the French, whilst bowing deeply, that the road was closed and that the good messieurs unfortunately had to consider themselves confined to the adjacent camp of their most gracious majesties William of Orange and Mary of England. His point was stressed further by the emergence of several levered musket barrels from the Dutch side.

Feuquiéres had lost his humour completely and as he leaned closer to the Comte, he slowly reached for his pistol hidden underneath the steed’s saddle. D’Artagnan discretely gestured for Catinat to do the same, who obeyed with a disturbed whisper.

“Our horses are tired, monsieur, we can’t hope to overcome them.”

The Comte smiled before raising his chin to the Dutch.

“At Linz, monsieur, I lead the charge of four hundred gendarmes and pistoliers alongside the Vicomte de Turenne against a foe ten times our numbers. Attempting to detain me when I am acting in the service of my most gracious sovereign with nothing but half a company’s worth of infantry is, I’m sorry to say so, against all common sense… Now, I must really ask you to stand your men down before blood is spilled.”

The Dutchman in the green overcoat laughed a laugh as if a smaller battery had been discharged somewhere in his throat and with a wave of his gloved hand bade his companion with the partisan to prepare quarters for their “guests”.

“I must really and truly beg your noble pardon, captain, but it seems as if the odds are thoroughly against you this morning. No matter whatever Papist gang you might have faced.”

D’Artagnan smiled a sly smile[1], “…never tell me the odds, monsieur…” and as he in one quick move drew his pistol from its holster behind his saddle, he added “…adieu!”

Then he discharged his weapon into the wondering face of the Dutch officer in the bottleneck green coat.

It was not only Dutchmen who participated on the side of William of Orange in what was to become the War of British Succession. This, however, is almost evident due to the fact that the coffins of the Prince of Orange and his subjects in the United Provinces as well as those of his allies in the Flemish Estates were practically empty. Furthermore not only was there no funds, but there was also no army to fund.

That is of course an oversimplification. The Dutch forces had been regrouped since their disastrous campaign in Austria, which had lead to the violent death of Frederick Henry in open battle against the Habsburg marshal Pappenheim, and were on the eve of commencement of hostilities a relatively powerful force – strong enough to defend the myriad of canals and dams of the United Provinces, but nowhere potent enough as to undertake an offensive singlehandedly, let alone attempt a seaborne invasion of the British Isles – which, of course, would be the prime objective of the war.

Thus William had to look abroad for forces strong enough to support his bid for the throne in the face of Stuart usurpation. He needed an army of great discipline with skilled commanders and a navy of, if not equal martial abilities, at least strength great enough to ensure the passage of the land based forces went without disastrous results.

An obvious choice would have been the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway who, with her massive navy and easily deployed army, could easily lead the supportive attack on the eastern coast of England that the Prince of Orange needed so badly. Unfortunately the House of Oldenburg who ruled the Nordic double monarchy had ties to the Stuarts and were besides that caught up in a greater gamble for control of Northern Europe in which they relied extensively on French subsidies and good will. Together with another French ally, Hohenzollern Brandenburg, the Danes hoped to quell the Swedish desire for expansion which had already brought them control of most of the Baltic coast as well as the former Habsburg enclave of Danzig.

The Catholic powers were of no use given their current state of intern chaos and even if they had been able to raise some form of usable military force, it would be ludicrous to suppose that they suddenly would forgive and forget the hatred which generations upon generations filled with war had sown between the United Provinces and Habsburg monarchies.

Eventually, through a serious of clandestine meetings between different parties and led by the English duke of Gloucester and an unnamed lady of noble birth, William established contacts to the only entity with the power he needed – the exiled forces of Parliament in Dublin.

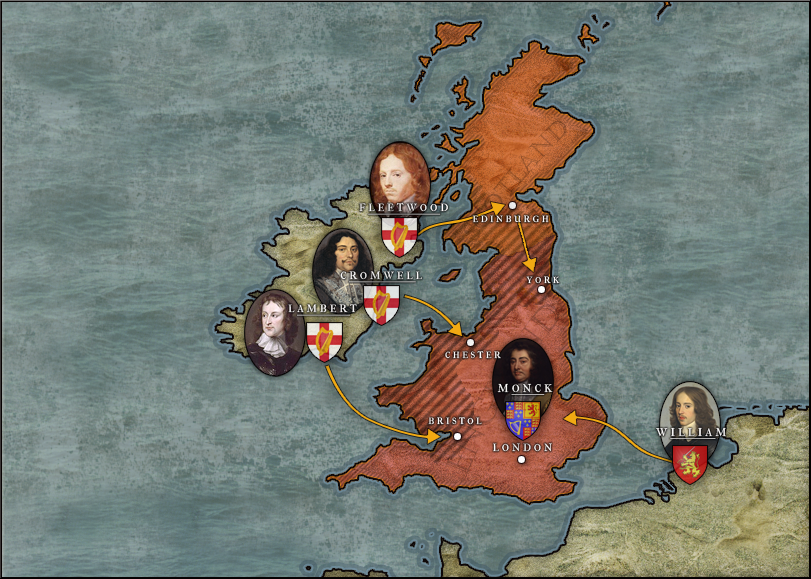

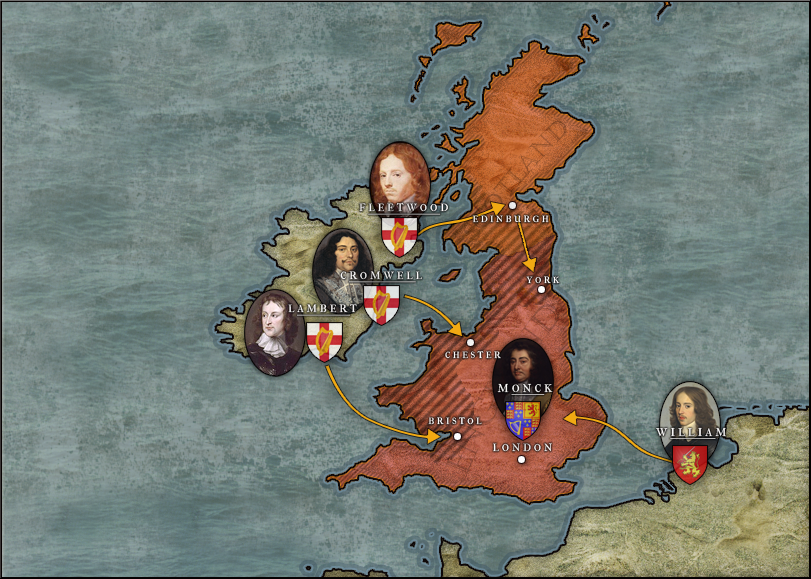

Map of the planned Dutch-Parliamentarian invasion or “Restoration” of England and Scotland. Areas outlined show territory which the parliamentarians should seize without much effort whilst William led his army towards London.

To Henry Cromwell and his chief lieutenants the prospect of having William take up the English, Scottish and Irish thrones did not seem as such a bad idea at all. The House of Orange was one of the great homes for Protestantism and the Prince himself was married to the sister of James II Stuart, so the pretext was certainly there despite the shaky legal foundation. However, and far more important, William’s invasion or “Glorious Revolution” gave the exiles an opportunity to exact revenge on the royalists and restore the traditions of the old parliament to the British isles – with a vengeance. That the new king would be severely indebted to them for their vital services in the coming war was only an extra bonus to an otherwise very reasonable deal.

William offered them very noble terms – a reinstitution of parliament, the application of Presbyterian ideals on the governing of the country and, of course, an immediate break with France and her continental system – thus opening fronts in the Americas where Puritan and Irish settlers could expand their domains and rights into Huguenot Canada.

Thus, in all its simplicity, what William suggested Cromwell was a parliamentarian institution which later monarchs would have to look to in search for legitimacy and a right to supremacy. It would be an ideal settlement of the former conflicts of the early 1600s, appealing to both the exiled old guard in Ireland such as Lambert and Fleetwood as well as to the members of James’ current parliament – distraught with his love for French advisors and Huguenot officials. It would be a benevolent monarch ruling with the approval and support of his loyal parliament over the three kingdoms of Britain – England, Scotland and Ireland. So, as the Prince of Orange left Amsterdam for the coast of Suffolk, scores of brigades from the New Model Army were embarked on the ships of the parliamentarian navy that soon streamed out of Dublin harbour enjoying favourable winds, across the Irish Sea and towards the cities of Bristol and Chester – whilst a third force made headway for the beaches of Scotland.

The question was now… how would James react?

And how would Nicolas?

Find out in the next update on Paris ne vaut pas une messe!

By the turn of the sixth decade of the 17th century one could be tempted to describe the geo-political situation on the European continent as a rather one sided affair - almost unilateral as some have gone on to write. Given the fact how French, Huguenot and Absolutionist armed forces, backed by a diplomatic corps of enormous élan, held the majority of central Europe, and its heartland, centred on the German Empire, firmly under the influence of the Louvre.

Yet the defining point of this era is not the temporary hegemony of one royal house and its precise religious practices. It is in turn, however, the paradox of the age that has attracted scholars – the paradox that even as the French lilies blossomed to their final glorious summer over the fields of old Europe, their time was coming to a rapid close.

The reason for this lay not with Habsburgs, Spaniards or Papists, but rather with the absolute success with which the Bourbons had stamped the leather-clad boots of their immense armies from the currents of the Ebro to the dark waters of the Danube. Across the channel in England and in the flat, tulip-covered Netherlands the changing rulers had, beforehand, always followed Paris’ lead when it came to the tending of the Protestant cause and the advancement of the Reformation.

Now, being sick with having become taken for granted by the rigorous Huguenot foreign department, the Dutch and the English and the Scots had all found the international situation with French arrogance unbearable. Strangled by its own achievements in the field and at the negotiation tables, the same Protestant Alliance that had arisen from the nascence of the armed conflict surrounding the wars between the Christian churches had now, seemingly, extinguished itself.

A battalion of French troops advances through a snow-covered landscape in the vicinity near the Netherlands whilst several companies to their rear are being prepared for deployment.

In The Hague a young and ambitious Prince of Orange had no intentions of being reduced to a loyal French satrap with a minor dependency whilst his neighbours where chained around him with iron forged in the mines of the Rhine valley and in the countryside of the British isles, peer and serf alike were fearing the Huguenot influence which James II Stuart seemed to revel so much in. Two thirds of the Protestant alliance were thus also caught in the paradox of the time. On one hand they were in numerically majority against France (two to one), but on the other they were very much in minority (France had gained far the most by the Religious Wars) – French wilful and condescending behaviour towards the English and Dutch allies had assured that.

On the great isles across the Channel, the commoners did not have the same physical ‘threat’ of the Huguenot Armées hanging over their heads, but they did enjoy having a sovereign who delighted his court by French plays, French cuisine, French services and French advisers. In this aspect the Dutch were fortunate with their increasingly Francophobic William of Orange. However, it wasn’t only the English and Scottish who were alarmed by the inconsistency of London’s reverence for Paris and its disdain for the disgruntled native aristocracy.

Dublin Castle also feared the implications an increasingly pro-French Stuart government could have on the fragile peace that had descended on the waters of the Irish Sea. Despite being exceptionally delighted and proud of their victory over the Absolutists in the War of 1657 where Oliver Cromwell and Charles Fleetwood had destroyed a Huguenot field army, the Parliamentarian strategists still shivered when they thought of a Royalist navy transporting French troops en masse to the shores of Ireland – an outcome all too easy to imagine for Dublin’s liking.

However, replacing James, who had surprisingly skilfully secured his inheritance at his father’s death, seemed downright impossible for the Parliamentarians who were still dealing with the troubles surrounding Oliver Cromwell’s passing years before. With the second son of Cromwell dead it rested upon the fourth of the late lieutenant general’s sons, Henry, to lead an uneasy coalition between himself, the skilled – albeit ageing - Charles Fleetwood and the immensely popular John Lambert. The native Irish royalty which was kept alive as a symbolic figureheads with which the Parliamentarians hoped to quell Irish resistance had no relevance for what the exiles thought of as a solely English matter of succession – therefore they had to look abroad for a substitute…

Organisation of the French infantry in 1672.

***

“Look to the North”

D’Artagnan jerked the reins backwards with his gauntleted hands and drove his freezing mount into a brutal stop on the gravel road, his exited breath visible in the morning cold as small clouds of smoke. It had been a long and harsh ride and all three were tired and battered. As the Comte gazed across the lead coloured waves and the grey foam of the icy Channel, he could feel a certain sense of dread and sensation beginning to work its way up his throat.

“Feuquiéres, hand me your telescope… act smartly for God’s sake!” The nearest of the two other musketeers lead his sweating horse to the Captain’s side and after a quick search in his ruck-sack hanging from the horse’s saddle produced the object which the Comte unfolded with nervous clumsiness.

Streaming out from far away, over the olive coloured and frost covered hills a line of ships were passing out to sea, their heavy oaken bulks breaking the waves before them. The foremost of the vessels slowly turned starbow revealing to the Comte an eerie row of long barrelled cannons protruding from her darkened battery hatches. Suddenly in the tallest mast a flag went up and it unfolded as the icy western wind caught it, making the standard flutter wildly – as if it by this design attempted to discharge itself from the mast which held it in captivity. In the morning light it became clear to the three spectators. Upon its maiden white linen a scarlet cross was wrought and beside it a lion rampant, holding in its claws a raised sword above its crowned head, was embodied – dancing on the fluttering cloth.

“The heraldry of the Dutch house alongside the colours of England’s parliament,” D’Artagnan exclaimed before finishing with a smirk “they must be on their way already. William certainly wastes no time.”

“With such an escadre the Dutch will be able to land and supply at least half a dozen battalions. Why would they do that? Where are they going, monsieur Capitaine?” enquired Catinat.

“I fear that they might wish to raise objections to James’ succession to the English throne… In a rather violent sort of way.” Both the young musketeers looked at him in disbelief. France, England and the United Provinces had been allies for generations. Families had arisen and had been extinguished in the slaughtering of the scores of wars all over the world which the Protestant powers had pursued in unity against the Catholic repression. Conflict between them would be akin to civil war…

The ships moved faster and faster as the wind caught hold of their bulging sails. Soon they would pass the curve of Pas de Calais and the guns of alert French forts. Would they pass unharmed? Would the Louvre order the batteries to fire on allies acting in enemy interests?

With the sea on their right side, the three riders made way from the road and down a small hill side covered in frozen weeds. Feuquiéres whistled a royalist air eerily, which was heard often in his company, as he guided his mount down the tricky path. When a short jump from his steed brought him in front, he turned around in his saddle and looked thoughtfully at the Comte.

“What to do now, monsieur? The Dutch are at sea, the Flemish behind the dunes are probably not going to enjoy a surprise visit from the three of us and Calais is all to far away so no fresh horses… God, I miss Germany.”

“…You miss being in a warm salon with pleasant company, is what you miss you lazy Papist. Stop your confession before you make us all believe in the heresy of saints!” Catinat interjected from the rear – adding extra emphasis by throwing the last of his rations – a dusty piece of crust – after Feuquiéres. D’Artagnan chuckled at his companions’ bickering, but couldn’t help feeling that after all, Feuquiéres might have figured it out alright.

The Comte D’Artagnan, captain of the first company of the King’s Musketeers, was one of the few veterans left in the Huguenot army who had fought with the Vicomte all the way since before his great victories.

As they followed the road below, the Comte suddenly felt uneasy once more. After a turn of the road he understood why.

The way was blocked by two large trunks of dead, rotten wood and behind it stood at least half a company’s worth of armed men covered under heavy cloaks and coats, their faces shielded from the damp cold by broad hats of filter. Their leader, a man of small statute and golden moustache, armed with a partisan raised himself upon the barricade and shouted in a coarse language that penetrated the silence of the scenery like bullets of lead through virgin flesh.

“Halt! in de naam van Oranje. Wie gaat er?”

Perplexed, Catinat brought his mount up on the sides of the two others so that the three musketeers now were lined up against the defenders with the Comte D’Artagnan in the middle. It was now he who now took it upon himself to answer.

“Nous sommes mousquetaries du roi et de la France, monsieur!...”

A mumble resounded throughout the ranks of the Dutch infantry, for that was the language they spoke the Captain noted, as the message was first translated and then debated amongst them. A bugle called somewhere within the moving forest of pikes and the colours in its midst shook in response to a energic drum roll. D’Artagnan could all too well imagine the pair of wooden sticks dancing on the drumhead as he had seen them do before on the fields of Bohemia and Germany whilst soldiers were deployed and entire sectors of troops moved to the whims of a marshal’s baton. Something lead him to the thought that his answer might not have been approproate...

With some difficulty another man climbed the interimistic ramparts. Clad in a bottlekneck green overcoat with a yellow silk scarf around his waist, he planted one dark brown jackboot in front of the other and announced to the French, whilst bowing deeply, that the road was closed and that the good messieurs unfortunately had to consider themselves confined to the adjacent camp of their most gracious majesties William of Orange and Mary of England. His point was stressed further by the emergence of several levered musket barrels from the Dutch side.

Feuquiéres had lost his humour completely and as he leaned closer to the Comte, he slowly reached for his pistol hidden underneath the steed’s saddle. D’Artagnan discretely gestured for Catinat to do the same, who obeyed with a disturbed whisper.

“Our horses are tired, monsieur, we can’t hope to overcome them.”

The Comte smiled before raising his chin to the Dutch.

“At Linz, monsieur, I lead the charge of four hundred gendarmes and pistoliers alongside the Vicomte de Turenne against a foe ten times our numbers. Attempting to detain me when I am acting in the service of my most gracious sovereign with nothing but half a company’s worth of infantry is, I’m sorry to say so, against all common sense… Now, I must really ask you to stand your men down before blood is spilled.”

The Dutchman in the green overcoat laughed a laugh as if a smaller battery had been discharged somewhere in his throat and with a wave of his gloved hand bade his companion with the partisan to prepare quarters for their “guests”.

“I must really and truly beg your noble pardon, captain, but it seems as if the odds are thoroughly against you this morning. No matter whatever Papist gang you might have faced.”

D’Artagnan smiled a sly smile[1], “…never tell me the odds, monsieur…” and as he in one quick move drew his pistol from its holster behind his saddle, he added “…adieu!”

Then he discharged his weapon into the wondering face of the Dutch officer in the bottleneck green coat.

***

It was not only Dutchmen who participated on the side of William of Orange in what was to become the War of British Succession. This, however, is almost evident due to the fact that the coffins of the Prince of Orange and his subjects in the United Provinces as well as those of his allies in the Flemish Estates were practically empty. Furthermore not only was there no funds, but there was also no army to fund.

That is of course an oversimplification. The Dutch forces had been regrouped since their disastrous campaign in Austria, which had lead to the violent death of Frederick Henry in open battle against the Habsburg marshal Pappenheim, and were on the eve of commencement of hostilities a relatively powerful force – strong enough to defend the myriad of canals and dams of the United Provinces, but nowhere potent enough as to undertake an offensive singlehandedly, let alone attempt a seaborne invasion of the British Isles – which, of course, would be the prime objective of the war.

Thus William had to look abroad for forces strong enough to support his bid for the throne in the face of Stuart usurpation. He needed an army of great discipline with skilled commanders and a navy of, if not equal martial abilities, at least strength great enough to ensure the passage of the land based forces went without disastrous results.

An obvious choice would have been the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway who, with her massive navy and easily deployed army, could easily lead the supportive attack on the eastern coast of England that the Prince of Orange needed so badly. Unfortunately the House of Oldenburg who ruled the Nordic double monarchy had ties to the Stuarts and were besides that caught up in a greater gamble for control of Northern Europe in which they relied extensively on French subsidies and good will. Together with another French ally, Hohenzollern Brandenburg, the Danes hoped to quell the Swedish desire for expansion which had already brought them control of most of the Baltic coast as well as the former Habsburg enclave of Danzig.

The Catholic powers were of no use given their current state of intern chaos and even if they had been able to raise some form of usable military force, it would be ludicrous to suppose that they suddenly would forgive and forget the hatred which generations upon generations filled with war had sown between the United Provinces and Habsburg monarchies.

Eventually, through a serious of clandestine meetings between different parties and led by the English duke of Gloucester and an unnamed lady of noble birth, William established contacts to the only entity with the power he needed – the exiled forces of Parliament in Dublin.

Map of the planned Dutch-Parliamentarian invasion or “Restoration” of England and Scotland. Areas outlined show territory which the parliamentarians should seize without much effort whilst William led his army towards London.

To Henry Cromwell and his chief lieutenants the prospect of having William take up the English, Scottish and Irish thrones did not seem as such a bad idea at all. The House of Orange was one of the great homes for Protestantism and the Prince himself was married to the sister of James II Stuart, so the pretext was certainly there despite the shaky legal foundation. However, and far more important, William’s invasion or “Glorious Revolution” gave the exiles an opportunity to exact revenge on the royalists and restore the traditions of the old parliament to the British isles – with a vengeance. That the new king would be severely indebted to them for their vital services in the coming war was only an extra bonus to an otherwise very reasonable deal.

William offered them very noble terms – a reinstitution of parliament, the application of Presbyterian ideals on the governing of the country and, of course, an immediate break with France and her continental system – thus opening fronts in the Americas where Puritan and Irish settlers could expand their domains and rights into Huguenot Canada.

Thus, in all its simplicity, what William suggested Cromwell was a parliamentarian institution which later monarchs would have to look to in search for legitimacy and a right to supremacy. It would be an ideal settlement of the former conflicts of the early 1600s, appealing to both the exiled old guard in Ireland such as Lambert and Fleetwood as well as to the members of James’ current parliament – distraught with his love for French advisors and Huguenot officials. It would be a benevolent monarch ruling with the approval and support of his loyal parliament over the three kingdoms of Britain – England, Scotland and Ireland. So, as the Prince of Orange left Amsterdam for the coast of Suffolk, scores of brigades from the New Model Army were embarked on the ships of the parliamentarian navy that soon streamed out of Dublin harbour enjoying favourable winds, across the Irish Sea and towards the cities of Bristol and Chester – whilst a third force made headway for the beaches of Scotland.

The question was now… how would James react?

And how would Nicolas?

Find out in the next update on Paris ne vaut pas une messe!

[1]And why would that be now? Catch the in-story reference.

Milady de Winter on the prowl, per chance?

It's very interesting to see the onset of the French Empire. Usually we only see its rise, not also its fall.

It's very interesting to see the onset of the French Empire. Usually we only see its rise, not also its fall.

Last edited:

Where did you get the map pictures and what filters did you use to give them the highlighted area effect?

France is actually going into decline? That seems somewhat improbable given the enormous power the French have gathered over the years. Anyway, it'll be nice to see the emergence of new powers to challenge the French behemoth.

Yay for the United Kingdom!

My guess is, France won't go to war right away. If it would, it would completely isolate themselves from the rest of Europe. No allies and conducting both land and naval warfare with one (or two if they join in later) enemies, would certainly make old enemies look at France once again. Actually, I think if they try to confirm their dominance by defending England, they will fall. And if they won't they will fall.

The future looks dark for France.

My guess is, France won't go to war right away. If it would, it would completely isolate themselves from the rest of Europe. No allies and conducting both land and naval warfare with one (or two if they join in later) enemies, would certainly make old enemies look at France once again. Actually, I think if they try to confirm their dominance by defending England, they will fall. And if they won't they will fall.

The future looks dark for France.

The future looks dark for France.

Yet, every time the future looks dark for France, it ends up in pain for everyone else.

Excellent return. D'Artagnan sure is a gambler.

Can the French navy defend her interests?

Can the French navy defend her interests?

Yet, every time the future looks dark for France, it ends up in pain for everyone else.

Indeed, especially those who get shot in the face

Indeed, especially those who get shot in the face

The real reason for The Man in the Iron Mask.

It will be interesting to see how this could mean the breakup of the French Empire. Even if a split in the protestant bloc isn't exactly desirable for Nicholas Henri, it surely shouldn't mean that his own empire was doomed?

Oh My God it's back, it's actually back! This is got to be one of the most epic and inspirational AARs I have ever. *regains composure*. sorry may have geeked out a bit  . Anyways, future sure looks grim for France, and looks like France might be getting knocked down a couple of pegs, but I am sure that it is nothing that it can't recover from over time. Keep it up.

. Anyways, future sure looks grim for France, and looks like France might be getting knocked down a couple of pegs, but I am sure that it is nothing that it can't recover from over time. Keep it up.

Damnation! Now I have to follow this AAR again! What a drag!  Instead of learning for my important Rennaisance/Reformation test i'm reading this update, i'm such a bad person.

Instead of learning for my important Rennaisance/Reformation test i'm reading this update, i'm such a bad person.

Great to have you back!

Great to have you back!