Chapter III: Part XLVI

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XLVI

December 5, 1936

From the brick tower parapet of St. Michael’s church, Oberst Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin trained his binoculars to the north and surveyed the approaches to Colchester. The countryside was smoldering as though coals had rained down from heaven, and the city’s skyline was almost indistinguishable. The bulk of his 6. Panzer-Regiment was rolling forward out there, and even though he could see little sign of them, the tankers were in close contact by wireless and semaphore. The staffers up in the churchtower with him had run a telephone line down to his command car parked below, and as radio reports came in, they marked platoons’ latest positions on a large 1:15,000 scale map.

The vicar had bravely tried to set fire to the tower as the Germans approached, to deny them the observation post, but von Senger’s men had intervened in time. The man and four local farmers were now locked under guard in the rectory. Since crossing the Colne at Wivenhoe the day before, the regiment had for the first time encountered significant franc-tireur activity. Although enemy regulars were hard to find in this stretch of the land, officers had reported nearly two dozen incidents with armed civilians. Panzers had driven into primitive ambushes -- trees downed across the road and men with firebombs lying in wait; barrels of gasoline ignited and rolled down from earthen berms; artillery shells rigged in the ground as land mines. Several times, men in the open country had fired shotguns or hunting rifles at passing tankers. A few troopers had been killed, and the Germans counted sixteen partisans in return. About half of them had been wearing “EDV” armbands, and the rest without a stitch of uniform. Operational orders mandated the execution of any unlawful combatants captured alive, but none had yet been taken.

Still, von Senger was taking no chances. He had most of a Schütze company posted around his field headquarters, and ordered machine guns deployed around St. Michael’s in case a larger British force managed to slip around the panzers and into the rear. Earlier that morning, one of his platoons had seized a large cache of arms on Roman Hill after being led there by a local boy, and his interrogators believed there were similar troves nearby.

Despite the stillness around the church, four kilometers ahead, the artillery thudded and boomed like a summer thunderstorm. It was now 1340, and 6. Panzer-Regiment was pressing its attack anew. Earlier, cavalry from the other side of the city had made contact with friendly lines at the fortified hamlet of Shrub End, followed by Jägers from Haase’s 3. Infanterie-Division, and it appeared that they had overrun several artillery batteries that had been blocking von Senger’s way. His priority now was to make up for lost time.

“Herr Oberst, a message from Major Lippert!”

von Senger turned to find one of his adjutants holding a yellow paper in his hand.

“1334. II. Bataillon has reached Colchester Cemetery,” the man read. “Anti-tank rifles within. Schütze to engage.”

“Good.” von Senger raised his binoculars again. “Good.”

Rolf Lippert’s battalion was driving northward, along and to the east of the Mersea road that ran into the center of Colchester. Tracks tearing up the ground of the Essex Regiment’s large suburban rifle range, Lippert’s panzers had advanced for nearly a kilometer without any casualties.

The sting of the anti-tank 2-pounders in the cemetery had been painful, and now von Senger could see through his binoculars two plumes of darker smoke where he reckoned Lippert was. He turned again to his adjutant and dictated a reply to the Major ordering him to press forward into the city. Then he dashed off a message detaching some of the Schützen from I. Panzer-Bataillon, which was advancing up the Berechurch road, about a thousand meters to the west of Lippert’s position. With infantry storming the cemetery from both sides, the Oberst hoped, the guns could be knocked out quickly.

All he could do now was wait. Many commanders would have bombarded their lieutenants with exhortations and requests for information, but von Senger knew that that would only distract them. The artillery rumbled on. After twenty frustrating minutes, word came from Lippert that the cemetery had been taken with moderate losses, and that a surrendered unit of Essexes was being sent to the rear.

II. Bataillon’s forward screens were now just 750 meters from the city center, and were encountering stiffening resistance as they neared the large Victorian barracks complex that formed the Essex Regiment’s headquarters. von Senger raised III Armeekorps on the radio and instructed them to halt the artillery barrage. von Weichs came on the channel personally, and after a brief conversation about the situation, the Generalleutnant agreed. The shelling stopped.

As von Senger waited for an update, he heard rumble of a lorry below and looked down onto the roadside next to the church. It was a commandeered British troop carrier with men in pioneer helmets hanging to the frame. Their captain dismounted and spoke with the guards at the churchyard gate before being shown in.

Within a minute, his adjutant introduced the man up in the belfry: “Pionier-Hauptmann Kopriva.”

von Senger shook his hand. “I am pleased.”

“We have neutralized seven pillboxes that were defending the approaches to the city. Unless reconnaissance has identified any more in that area, then I request that my unit be detached for independent action to the west.”

“Denied, I’m afraid, Hauptmann. We may have need of you yet, and I’ve had reports of enemy armor on the London road. You may remain here until further orders.”

“Major Lippert for you,” an adjutant interrupted.

“Excuse me.” von Senger took the radiotelephone. “Major, what is going on up there?”

“We are ready to launch a frontal assault on the city center upon your order, Herr Oberst.”

“Well done. What is the enemy strength there?”

“We destroyed three light tanks, but aside from that only infantry.” Gunfire sparked and crackled in the background. “I’d say a battalion and a half. Largely holed up in buildings and cellars. It’ll be tricky going for the panzers, but the Schützen will lead the way.”

“Yes. Now listen, Major.” The Oberst waved an adjutant over with the 1:15,000 map and traced his finger into the city. “The objective is the railway station in the city center. From there, Haase’s men are just four blocks north, along High street. They report that they took Colchester castle around noon. Haase’s men are the anvil against which our armor will hammer the city open. Once the station is taken, the defenders will be split in half, and can be cleared systematically. Is that clear?”

“Yes, Herr Oberst.”

“We will wait until all assault elements are in place. Take a defensive posture and await my order. I am sending up a Sturmpionier detachment to assist you with the cellars and strongpoints.” He held the receiver away from his mouth. “Hauptmann Kopriva, how many effectives do you have?”

“Sixty-one.”

“That’s 61 assault pioneers, Major. Await my order.”

Within fifteen minutes, all three of his battalions were poised around the center of Colchester. von Senger delayed the attack to call von Weichs, inquiring about the continued absence of air cover. The grandfatherly general’s adjutants kept him -- rather surprisingly -- waiting.

A reek of smoke still rose from the city, but there was now an eerie silence. The air was empty, and the artillery had stopped. If there was small arms fire being exchanged, the sound didn’t reach St. Michael’s.

He had been here before, in 1912, and knew the history intimately. Perhaps then, still a student, he had even ridden past this church, unable to comprehend the sweep of modern history that would take him back here. He remembered the day he had spent here so clearly. Those roads that were now filled by his panzers curved and undulated, following the shapes of the time-worn earthen ramparts raised by the first barbarians that settled here.

Later, as Camelodunum, Colchester had been the capital of Roman Britain. Emperor Claudius had traveled there personally to receive homage from the Briton chiefs, and the city had been a hub of culture and civilization for nearly four centuries. At Oxford, von Senger had been exposed to the theory that over time, this period became mythologized as a golden age. The legends grew, and in the songs of the bards, Camelodunum took on a slightly altered name -- Camelot. As Colchester, it was the setting of the nursery rhymes “Old King Cole” and “Humpty Dumpty,” and home of Shakespeare’s Cymbeline. History was once again knocking on the city’s door.

“von Weichs.”

He jerked the receiver to his mouth. “Herr Generalleutnant, I am concerned that our Luftwaffe support has been withdrawn. What’s going on?”

“I don’t quite know, von Senger, but it sounds like something bad down south. I can’t get a single propeller for anything.”

“Shall I proceed with the assault, nonetheless?”

“Absolutely.”

This was all the final encouragement von Senger needed. At 1435, he plunged all three panzer battalions into the city’s gut.

With little in the way of anti-tank weapons, the remaining defenders had a hard time slowing their momentum. Some streets were blocked with rubble or overturned automobiles, but the panzers’ machine guns were enough to keep the Essexes’ heads down while assault pioneers cleared the way forward. Two Schütze companies stormed the old barracks while a third secured Abbey field, the open green just west of the city center. It had been an encampment for the emergency volunteers called up to swell the Colchester garrison, but the past days’ shelling had reduced the tent city to a cratered wasteland. With many of the taller buildings in ruins, there were few vantages for Lewis guns or sharpshooters, and the Germans crossed with minimal casualties.

Block by block, the armor rolled on, as infantry engaged any bypassed strongpoints. The enemy soldiers fought less cohesively now -- the close-quarters combat separated them into small and isolated units which fought haphazardly, if no less bravely. At any rate, many of the remaining defenders were remnants of other formations that had been shattered closer to the coast, and had straggled back to Colchester during the long nights.

von Senger had received conflicting reports about what proportion of the civilian population was still stuck in the city. The Luftwaffe believed that most of the inhabitants had fled over the preceding forty-eight hours, but captive locals like the vicar of St. Michael’s insisted that at least two thirds of Colchester’s non-combatants were still trapped there. The problem troubled Oberst von Senger deeply, but for many reasons, he found it easier to conclude that the Luftwaffe estimates were more trustworthy.

At 1456, Major Lippert’s II. Bataillon radioed that the old barracks had been captured. Bitter fighting continued to the north as German forces advanced to within view of the railway station. Soon, the commander of III. Bataillon reported that his panzers had linked up with Generalmajor Haase’s infantrymen on the viaduct over the tracks about 500 meters to the east. von Senger urged them on without delay.

Just moments into the final assault, a British corporal mounted the roof of the station with a scrap of white cloth, announcing that his commander wished to discuss terms. The colonel of the regiment had been captured during the storming of the barracks, and he was now brought forward to negotiate the surrender.

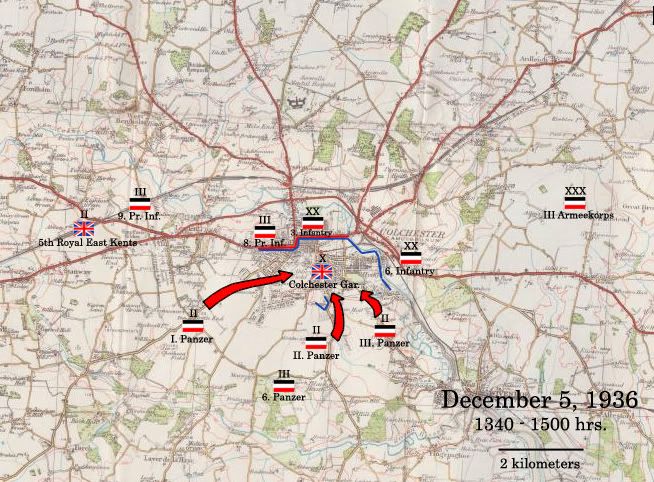

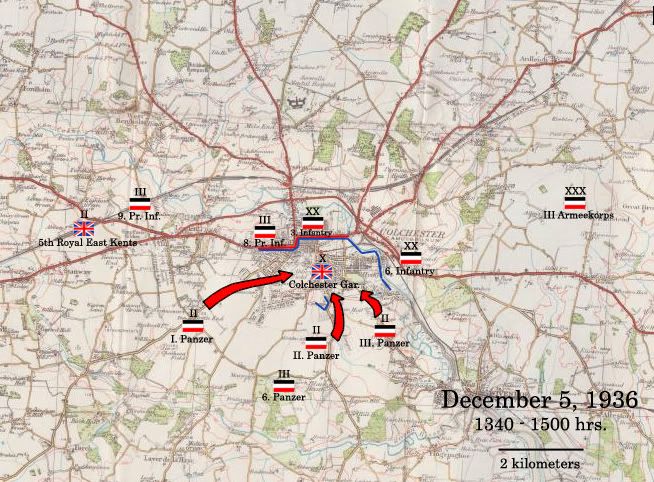

Battle of Colchester, afternoon of December 5.

It was not long before astonished reports came back to von Senger at St. Michael’s church. The station complex had been packed with nearly three thousand men -- about a seventh Essexes, but the rest a hodgepodge of Territorials, Auxiliaries and Emergency Defense Volunteers. Other than the regulars, few of them had more than a few rounds of ammunition, and all were dirty, cold and exhausted after the past days’ fighting. Other reports came over the radio of the civilians’ fate. The officers were still trying to get an accurate count, but according to the mayor, at least fifteen thousand men, women and children were huddled in the city’s crowded cellars. In the chaos, the true number could be double that.

The Germans consolidated their lines and cleared holdouts into the early-falling evening. von Senger’s regiment counted 97 dead. To the north, Haase’s bloodied infantrymen had lost 210 more. And still, no sign of the Luftwaffe.

Oberst von Senger looked north one more time before going down from the churchtower. A last company of Essexes was holed up in the Paxman diesel engine factory, but with Colchester effectively taken, there was no point in a wasteful assault during the night. It would be well for both sides if they gave themselves up before morning. In the meanwhile, III Armeekorps had fifteen hours of darkness to repair the Colne bridges and get started rolling inland again. To the west, the London road lay open like a gate swinging in the wind.

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XLVI

December 5, 1936

From the brick tower parapet of St. Michael’s church, Oberst Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin trained his binoculars to the north and surveyed the approaches to Colchester. The countryside was smoldering as though coals had rained down from heaven, and the city’s skyline was almost indistinguishable. The bulk of his 6. Panzer-Regiment was rolling forward out there, and even though he could see little sign of them, the tankers were in close contact by wireless and semaphore. The staffers up in the churchtower with him had run a telephone line down to his command car parked below, and as radio reports came in, they marked platoons’ latest positions on a large 1:15,000 scale map.

The vicar had bravely tried to set fire to the tower as the Germans approached, to deny them the observation post, but von Senger’s men had intervened in time. The man and four local farmers were now locked under guard in the rectory. Since crossing the Colne at Wivenhoe the day before, the regiment had for the first time encountered significant franc-tireur activity. Although enemy regulars were hard to find in this stretch of the land, officers had reported nearly two dozen incidents with armed civilians. Panzers had driven into primitive ambushes -- trees downed across the road and men with firebombs lying in wait; barrels of gasoline ignited and rolled down from earthen berms; artillery shells rigged in the ground as land mines. Several times, men in the open country had fired shotguns or hunting rifles at passing tankers. A few troopers had been killed, and the Germans counted sixteen partisans in return. About half of them had been wearing “EDV” armbands, and the rest without a stitch of uniform. Operational orders mandated the execution of any unlawful combatants captured alive, but none had yet been taken.

Still, von Senger was taking no chances. He had most of a Schütze company posted around his field headquarters, and ordered machine guns deployed around St. Michael’s in case a larger British force managed to slip around the panzers and into the rear. Earlier that morning, one of his platoons had seized a large cache of arms on Roman Hill after being led there by a local boy, and his interrogators believed there were similar troves nearby.

Despite the stillness around the church, four kilometers ahead, the artillery thudded and boomed like a summer thunderstorm. It was now 1340, and 6. Panzer-Regiment was pressing its attack anew. Earlier, cavalry from the other side of the city had made contact with friendly lines at the fortified hamlet of Shrub End, followed by Jägers from Haase’s 3. Infanterie-Division, and it appeared that they had overrun several artillery batteries that had been blocking von Senger’s way. His priority now was to make up for lost time.

“Herr Oberst, a message from Major Lippert!”

von Senger turned to find one of his adjutants holding a yellow paper in his hand.

“1334. II. Bataillon has reached Colchester Cemetery,” the man read. “Anti-tank rifles within. Schütze to engage.”

“Good.” von Senger raised his binoculars again. “Good.”

Rolf Lippert’s battalion was driving northward, along and to the east of the Mersea road that ran into the center of Colchester. Tracks tearing up the ground of the Essex Regiment’s large suburban rifle range, Lippert’s panzers had advanced for nearly a kilometer without any casualties.

The sting of the anti-tank 2-pounders in the cemetery had been painful, and now von Senger could see through his binoculars two plumes of darker smoke where he reckoned Lippert was. He turned again to his adjutant and dictated a reply to the Major ordering him to press forward into the city. Then he dashed off a message detaching some of the Schützen from I. Panzer-Bataillon, which was advancing up the Berechurch road, about a thousand meters to the west of Lippert’s position. With infantry storming the cemetery from both sides, the Oberst hoped, the guns could be knocked out quickly.

All he could do now was wait. Many commanders would have bombarded their lieutenants with exhortations and requests for information, but von Senger knew that that would only distract them. The artillery rumbled on. After twenty frustrating minutes, word came from Lippert that the cemetery had been taken with moderate losses, and that a surrendered unit of Essexes was being sent to the rear.

II. Bataillon’s forward screens were now just 750 meters from the city center, and were encountering stiffening resistance as they neared the large Victorian barracks complex that formed the Essex Regiment’s headquarters. von Senger raised III Armeekorps on the radio and instructed them to halt the artillery barrage. von Weichs came on the channel personally, and after a brief conversation about the situation, the Generalleutnant agreed. The shelling stopped.

As von Senger waited for an update, he heard rumble of a lorry below and looked down onto the roadside next to the church. It was a commandeered British troop carrier with men in pioneer helmets hanging to the frame. Their captain dismounted and spoke with the guards at the churchyard gate before being shown in.

Within a minute, his adjutant introduced the man up in the belfry: “Pionier-Hauptmann Kopriva.”

von Senger shook his hand. “I am pleased.”

“We have neutralized seven pillboxes that were defending the approaches to the city. Unless reconnaissance has identified any more in that area, then I request that my unit be detached for independent action to the west.”

“Denied, I’m afraid, Hauptmann. We may have need of you yet, and I’ve had reports of enemy armor on the London road. You may remain here until further orders.”

“Major Lippert for you,” an adjutant interrupted.

“Excuse me.” von Senger took the radiotelephone. “Major, what is going on up there?”

“We are ready to launch a frontal assault on the city center upon your order, Herr Oberst.”

“Well done. What is the enemy strength there?”

“We destroyed three light tanks, but aside from that only infantry.” Gunfire sparked and crackled in the background. “I’d say a battalion and a half. Largely holed up in buildings and cellars. It’ll be tricky going for the panzers, but the Schützen will lead the way.”

“Yes. Now listen, Major.” The Oberst waved an adjutant over with the 1:15,000 map and traced his finger into the city. “The objective is the railway station in the city center. From there, Haase’s men are just four blocks north, along High street. They report that they took Colchester castle around noon. Haase’s men are the anvil against which our armor will hammer the city open. Once the station is taken, the defenders will be split in half, and can be cleared systematically. Is that clear?”

“Yes, Herr Oberst.”

“We will wait until all assault elements are in place. Take a defensive posture and await my order. I am sending up a Sturmpionier detachment to assist you with the cellars and strongpoints.” He held the receiver away from his mouth. “Hauptmann Kopriva, how many effectives do you have?”

“Sixty-one.”

“That’s 61 assault pioneers, Major. Await my order.”

Within fifteen minutes, all three of his battalions were poised around the center of Colchester. von Senger delayed the attack to call von Weichs, inquiring about the continued absence of air cover. The grandfatherly general’s adjutants kept him -- rather surprisingly -- waiting.

A reek of smoke still rose from the city, but there was now an eerie silence. The air was empty, and the artillery had stopped. If there was small arms fire being exchanged, the sound didn’t reach St. Michael’s.

He had been here before, in 1912, and knew the history intimately. Perhaps then, still a student, he had even ridden past this church, unable to comprehend the sweep of modern history that would take him back here. He remembered the day he had spent here so clearly. Those roads that were now filled by his panzers curved and undulated, following the shapes of the time-worn earthen ramparts raised by the first barbarians that settled here.

Later, as Camelodunum, Colchester had been the capital of Roman Britain. Emperor Claudius had traveled there personally to receive homage from the Briton chiefs, and the city had been a hub of culture and civilization for nearly four centuries. At Oxford, von Senger had been exposed to the theory that over time, this period became mythologized as a golden age. The legends grew, and in the songs of the bards, Camelodunum took on a slightly altered name -- Camelot. As Colchester, it was the setting of the nursery rhymes “Old King Cole” and “Humpty Dumpty,” and home of Shakespeare’s Cymbeline. History was once again knocking on the city’s door.

“von Weichs.”

He jerked the receiver to his mouth. “Herr Generalleutnant, I am concerned that our Luftwaffe support has been withdrawn. What’s going on?”

“I don’t quite know, von Senger, but it sounds like something bad down south. I can’t get a single propeller for anything.”

“Shall I proceed with the assault, nonetheless?”

“Absolutely.”

This was all the final encouragement von Senger needed. At 1435, he plunged all three panzer battalions into the city’s gut.

With little in the way of anti-tank weapons, the remaining defenders had a hard time slowing their momentum. Some streets were blocked with rubble or overturned automobiles, but the panzers’ machine guns were enough to keep the Essexes’ heads down while assault pioneers cleared the way forward. Two Schütze companies stormed the old barracks while a third secured Abbey field, the open green just west of the city center. It had been an encampment for the emergency volunteers called up to swell the Colchester garrison, but the past days’ shelling had reduced the tent city to a cratered wasteland. With many of the taller buildings in ruins, there were few vantages for Lewis guns or sharpshooters, and the Germans crossed with minimal casualties.

Block by block, the armor rolled on, as infantry engaged any bypassed strongpoints. The enemy soldiers fought less cohesively now -- the close-quarters combat separated them into small and isolated units which fought haphazardly, if no less bravely. At any rate, many of the remaining defenders were remnants of other formations that had been shattered closer to the coast, and had straggled back to Colchester during the long nights.

von Senger had received conflicting reports about what proportion of the civilian population was still stuck in the city. The Luftwaffe believed that most of the inhabitants had fled over the preceding forty-eight hours, but captive locals like the vicar of St. Michael’s insisted that at least two thirds of Colchester’s non-combatants were still trapped there. The problem troubled Oberst von Senger deeply, but for many reasons, he found it easier to conclude that the Luftwaffe estimates were more trustworthy.

At 1456, Major Lippert’s II. Bataillon radioed that the old barracks had been captured. Bitter fighting continued to the north as German forces advanced to within view of the railway station. Soon, the commander of III. Bataillon reported that his panzers had linked up with Generalmajor Haase’s infantrymen on the viaduct over the tracks about 500 meters to the east. von Senger urged them on without delay.

Just moments into the final assault, a British corporal mounted the roof of the station with a scrap of white cloth, announcing that his commander wished to discuss terms. The colonel of the regiment had been captured during the storming of the barracks, and he was now brought forward to negotiate the surrender.

Battle of Colchester, afternoon of December 5.

It was not long before astonished reports came back to von Senger at St. Michael’s church. The station complex had been packed with nearly three thousand men -- about a seventh Essexes, but the rest a hodgepodge of Territorials, Auxiliaries and Emergency Defense Volunteers. Other than the regulars, few of them had more than a few rounds of ammunition, and all were dirty, cold and exhausted after the past days’ fighting. Other reports came over the radio of the civilians’ fate. The officers were still trying to get an accurate count, but according to the mayor, at least fifteen thousand men, women and children were huddled in the city’s crowded cellars. In the chaos, the true number could be double that.

The Germans consolidated their lines and cleared holdouts into the early-falling evening. von Senger’s regiment counted 97 dead. To the north, Haase’s bloodied infantrymen had lost 210 more. And still, no sign of the Luftwaffe.

Oberst von Senger looked north one more time before going down from the churchtower. A last company of Essexes was holed up in the Paxman diesel engine factory, but with Colchester effectively taken, there was no point in a wasteful assault during the night. It would be well for both sides if they gave themselves up before morning. In the meanwhile, III Armeekorps had fifteen hours of darkness to repair the Colne bridges and get started rolling inland again. To the west, the London road lay open like a gate swinging in the wind.

Last edited: