Chapter III: Part XLIII

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XLIII

December 4, 1936

In the gray morning mist, the commander of 6. Panzer-Regiment stood atop an armored car near Wivenhoe, watching the bridging work through his field glasses.

Oberst Fridolin Rudolf Theodor von Senger und Etterlin was no stranger to Britain. The son of an ancient line of high Franconian nobility, he had won a Rhodes scholarship in 1911 and read History and Philosophy, Politics & Economics at St. John’s College for the last two years before the war. He had served with great distinction on the Western Front, winning both classes of the 1914 Iron Cross and was made a knight of the Order of the Zähringer Lion by his home state of Baden. He had retained a deep appreciation for the English people, though, and after the war resumed correspondence and frequent visits with many of his Oxford friends. Conversant in half a dozen languages, he had traveled widely between the wars, and enjoyed assurance of hospitality from Edinburgh to Cairo. He was at once monk-like in self-denial and eminently cultured in matters of the soul -- known widely as a lover of opera, Beaux Arts architecture and classical music. A devout Roman Catholic, he delighted in sparring with Protestant theologians on Barth, Weisse and Blumhardt. Professors of Classics, meanwhile, often came calling at his Bavarian estate to take up Virgil or Ovid.

Simultaneously a world-class equestrian, he had been an instructor at the Hanover Calvary School in the bleak years after Versailles, and later an officer in the cavalry inspectorate in Berlin. There, von Senger had forged connections with many of the men who would give birth to the Panzerwaffe within Hitler’s reborn Wehrmacht. With the coming of the present war, he had been singled out as one of the most promising field-grade armor commanders, and already promoted two grades since the previous year.

He had come across to England on the Freiburg -- formerly the French liner Paris -- along with many of the regiment’s tankers, docking at Harwich on December second. By the afternoon of the third, the regiment was rolling westward up the Harwich road. To the north, 3. Infanterie-Division had reached the outskirts of Colchester just before dark, and found the opposite bank of the Colne strongly fortified. This historic city of 50,000 people had been the heart of Roman Britain, and was now a major producer of diesel engines and aircraft parts. Now, it seemed to be shaping up as the key to British defenses in the region.

Winded forward elements of 6. Infanterie made contact at the southeastern edge of the city around 2130. Reports quickly filtered back to Harwich. As British forces had fallen back, they had destroyed bridges and felled trees across the roads. Now, they were safely across the first major river in Essex, and had blown the bridges in the Germans’ faces.

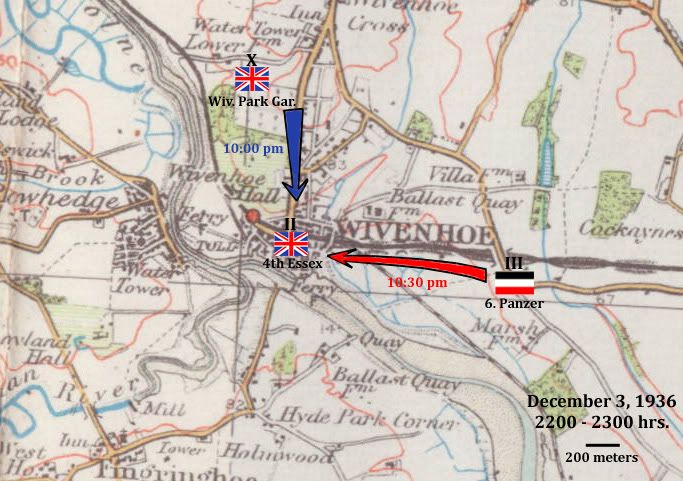

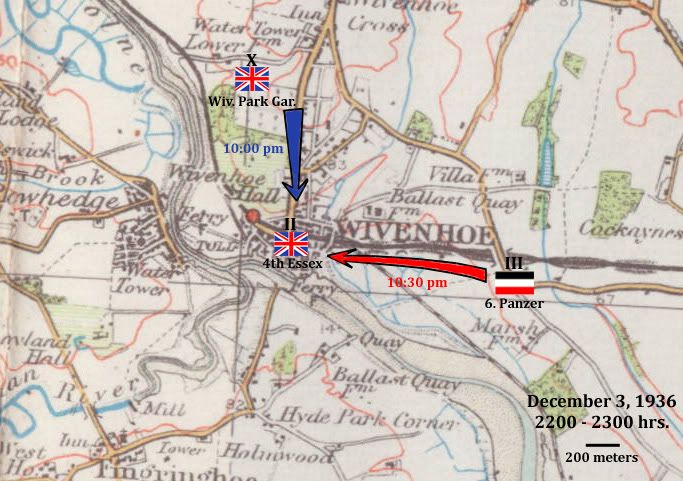

As 6. Panzer clattered down the darkened road trying to catch up with the infantry, Generalleutnant von Weichs had ordered them overland to a point further to the south. von Senger was charged with taking the town of Wivenhoe, which nestled against the east bank of the Colne some 5 kilometers downstream from Colchester.

Colne river, several kilometers downstream from Wivenhoe.

The town was defended by a battalion of Essex regulars and supported by almost two thousand Territorial Army inductees who had been billeted nearby. A confused battle ensued in the dark, as jittery garrison sentries mistook the reinforcements for Germans and lit up with everything they had on the stunned Territorials. At last, von Senger’s panzers came rolling up, following the sunken rail bed running into Wivenhoe.

The sudden appearance of the tanks seemed to shake the British out of their hysteria, and a battery of 2-pounders dug in east of the town opened fire on the tracks. Three Panzer Is were disabled before von Senger even learned that contact had been made. Pulling his units hurriedly back, he reformed his leading battalion to advance cross country along a sweeping 900 meter front. Silhouetted by flares from both sides, 51 panzers crashed through fences and hedges, churning fallow fields to dust as their commanders sighted on the square belfry of the town church. The enemy guns cracked again.

British artillerymen man a 2-pounder. December 3, Essex.

From his headquarters section 500 meters back on an overpass above the railway, Oberst von Senger had seen several columns of smoke and red flames bloom from the low ground just out of sight. He had radioed his company commanders for a report. The guns -- they counted eight -- were well protected behind a series of earthen berms, and were at such close range that even glancing hits were punching through the Panzer Is’ paper-thin armor.

On the other hand, the close range allowed the British only a few minutes of shooting before von Senger’s tanks were on top of them. The advance swept onward, slamming into the Essexes arrayed outside the town and pushing onward into Wivenhoe.

Wivenhoe, night of December 3.

Two hours of intense fighting ensued, as I. Panzer-Bataillon systematically cleared street after street. With the 2-pounders overrun, the British infantry had scant anti-tank weaponry -- aside from a single Boer War-vintage elephant rifle that Duff Cooper had assigned the garrison for just such an occasion. As von Senger threw his supporting Schütze troops into the attack, the British withdrew to the town center and the cover it offered. The German column battering its way down Hamilton road toward the railway station found itself stymied at the High street intersection. Several automobiles had been overturned to block the way forward, with tangles of concertina wire stretching out in front of them from sidewalk to sidewalk. A pair of Vickers machine guns sandbagged between the cars were spitting tracers down the road.

Probing the British perimeter, von Senger had found most of the defenders holed up in an area of three square blocks west of High street. He had ordered a halt while he dispatched his second battalion to disperse a counterattack from the north by a large but hesitant force of Territorials. Major Rolf Lippert, one of von Senger’s cavalry protégés, had ordered his II. Panzer-Bataillon up the Colchester road running north from Wivenhoe -- and into a wooded park where the enemy had been loitering since the start of the battle. The two forces met sooner than expected at the outskirts of the town, and the surprised tankers had started firing wildly, swerving across the park trying to run down the dark shapes that seemed to spring out of the ground itself. The startling violence of the performance quickly set the British to flight. von Senger had ordered Lippert not to pursue.

By 0145, von Senger was ready to commence the final assault on the center of Wivenhoe. Standing orders dictated that he try to obtain a surrender, though, so another hour and half elapsed as messages were traded back and forth across the lines. Finally, word arrived that the British major commanding the defense had agreed to negotiate terms at the farmhouse outside the town that von Senger was now using as a headquarters and field hospital. Another hour passed, but the officers on the battle line reported that despite continued messages, no commanding officer was forthcoming. The British were clearly stalling. The disposition and numbers of other enemy forces on the east side of the Colne still wasn’t fully clear, and von Senger couldn’t rule out the possibility that significant units had moved up from Clacton-on-Sea in the dark and were preparing to strike him from behind. Nonetheless, an all-out out fight for the now-surrounded town center would have been wasteful for both sides, and von Senger refused to consider it unless absolutely necessary. He sent word back across the lines: the defenders had fifteen minutes to surrender unconditionally. Still nothing.

Running out of options, von Senger ordered a limited attack on one side of the perimeter, aimed at taking the railway station. Two Schütze companies converged on the station from two sides supported by a four-tank platoon of Lippert’s panzers. The Essexes had clung bitterly to their positions, but were soon driven back. The Germans picking their way through the ruined station house counted 37 kettle-helmeted dead.

At last, just before 0400, Wivenhoe’s surviving defenders had surrendered. Taking the town had cost von Senger 98 killed and a surprisingly high 17 of his tanks out of action. Inquiring as to the cause, he had been relieved to hear that most of the latter losses would be recoverable. As it happened, nine of I. Bataillon’s Panzer Is had merely blundered into a series of dry irrigation ditches in their sprint toward the anti-tank guns at the start of the battle. Their vehicles stuck -- and in one case flipped -- in the line of fire, the crews had thrown open their hatches and taken for the rear.

As his Feldgendarmes marched the prisoners to the rear, von Senger drove forward to the riverside quays. There were no bridges this far downstream, but the opposite bank was lined with concrete pillboxes. Every now and then, one of them would spray a rope of bright tracers across the water at Germans who dallied too long in the open. His men were hard at work emplacing half a dozen PaK 36s along the flood wall.

The positions were at practically point-blank range for the German gunners, and the Colne was rather low on its banks, exposing great stretches of silty sand on each bank. Soon, their slender barrels were puffing orange flashes and thick cordite smoke -- even in the dark, it was almost impossible to miss. More difficult, though, was hitting for effect, as even these hastily-constructed casemates were strong enough to repel anything but a perfect strike.

German gunners suppress a British patrol sighted on the west bank of the Colne. Morning of December 4.

As the cross-river duel played out, von Weichs radioed von Senger with word that the schedule had been pushed up. The situation in the Channel was still “fluid,” he said, and although HKK had planned landings later that morning at Brightlingsea, at the mouth of the Colne, changing transport conditions had necessitated that a force of torpedo boats do the job in the dark. The force, consisting of Kondor, Seeadler and a pair of minesweepers, had passed the Colne bar at 0230, and disgorged two Pionier companies straight onto the Brightlingsea beach after finding the docks dismantled. The town had fallen quickly, he said, and the minesweepers were now towing a string of pioneer barges upriver to begin bridging work.

Around the time the barges were projected to arrive, von Weichs had called again with a complication. The torpedo boat Seeadler had managed to beach itself on one of the Colne’s treacherous sandbars, and the pioneers had frantically tried to free it before first light, only to conclude that the ship was held too firmly in the muck to have any hope. The barges were on their way after all.

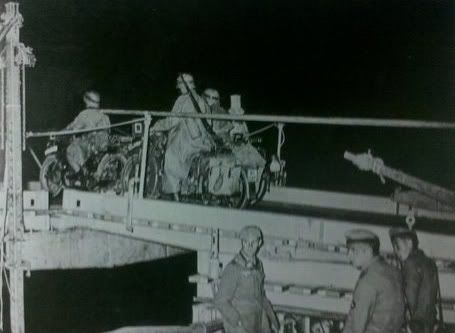

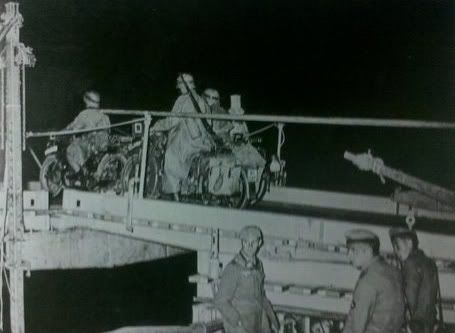

By 0500, the pillboxes had been silenced, and a platoon of von Senger’s men had motored across the river in commandeered launches to complete their destruction. The minesweepers came into view at 0517, and had promptly begun construction work at the Wivenhoe quays. Working under frightfully visible carbon arc work lamps, they had set about bolting together prefabricated sections of a light-use bridge. The Colne was only 50 meters wide here, and the assembly went quickly. The bridge wouldn’t be strong enough to support von Senger’s panzers, but would at least allow him to get enough men across to secure the west bank until morning. Less than two hours later, the first German motorcycle troops crossed the Colne, followed by most of 6. Panzer’s infantry.

Kradschützen cross an improvised bridge over the Colne at Wivenhoe. Early morning of December 4.

Now, it was getting light, and the pioneers were hard at work on another bridge, just downstream of the first one, that would be able to support the weight of tanks, trucks and armored cars. The engineers hoped to have it ready by mid-afternoon.

von Senger lowered his binoculars and looked out over Wivenhoe. Several trails of sooty, brownish smoke were slowly drifting high into the air. The rumble of distant artillery reminded him that in the rest of Essex, the day’s combat was only just beginning. While the Kradschütze motorcyclists pushed westward to conduct reconnaissance, the rest of 6. Panzer-Regiment tried to get what rest it could. While the pioneers worked, the men might be able to get five or six hours of sleep. Then on they would push over the Colne and through the long night back up north toward Colchester. von Weichs wanted the battle for the city decided on December fifth. It seemed that the British were trying to make the river their final stop line in Essex, the Generalleutnant said, and a swift knockout blow to Colchester would undermine the enemy’s defenses all the way to London.

Raising Major Lippert on the radio, von Senger gave his final orders for a defensive line around Wivenhoe, then slipped into the back of his armored car for a few hours’ rest.

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XLIII

December 4, 1936

In the gray morning mist, the commander of 6. Panzer-Regiment stood atop an armored car near Wivenhoe, watching the bridging work through his field glasses.

Oberst Fridolin Rudolf Theodor von Senger und Etterlin was no stranger to Britain. The son of an ancient line of high Franconian nobility, he had won a Rhodes scholarship in 1911 and read History and Philosophy, Politics & Economics at St. John’s College for the last two years before the war. He had served with great distinction on the Western Front, winning both classes of the 1914 Iron Cross and was made a knight of the Order of the Zähringer Lion by his home state of Baden. He had retained a deep appreciation for the English people, though, and after the war resumed correspondence and frequent visits with many of his Oxford friends. Conversant in half a dozen languages, he had traveled widely between the wars, and enjoyed assurance of hospitality from Edinburgh to Cairo. He was at once monk-like in self-denial and eminently cultured in matters of the soul -- known widely as a lover of opera, Beaux Arts architecture and classical music. A devout Roman Catholic, he delighted in sparring with Protestant theologians on Barth, Weisse and Blumhardt. Professors of Classics, meanwhile, often came calling at his Bavarian estate to take up Virgil or Ovid.

Simultaneously a world-class equestrian, he had been an instructor at the Hanover Calvary School in the bleak years after Versailles, and later an officer in the cavalry inspectorate in Berlin. There, von Senger had forged connections with many of the men who would give birth to the Panzerwaffe within Hitler’s reborn Wehrmacht. With the coming of the present war, he had been singled out as one of the most promising field-grade armor commanders, and already promoted two grades since the previous year.

He had come across to England on the Freiburg -- formerly the French liner Paris -- along with many of the regiment’s tankers, docking at Harwich on December second. By the afternoon of the third, the regiment was rolling westward up the Harwich road. To the north, 3. Infanterie-Division had reached the outskirts of Colchester just before dark, and found the opposite bank of the Colne strongly fortified. This historic city of 50,000 people had been the heart of Roman Britain, and was now a major producer of diesel engines and aircraft parts. Now, it seemed to be shaping up as the key to British defenses in the region.

Winded forward elements of 6. Infanterie made contact at the southeastern edge of the city around 2130. Reports quickly filtered back to Harwich. As British forces had fallen back, they had destroyed bridges and felled trees across the roads. Now, they were safely across the first major river in Essex, and had blown the bridges in the Germans’ faces.

As 6. Panzer clattered down the darkened road trying to catch up with the infantry, Generalleutnant von Weichs had ordered them overland to a point further to the south. von Senger was charged with taking the town of Wivenhoe, which nestled against the east bank of the Colne some 5 kilometers downstream from Colchester.

Colne river, several kilometers downstream from Wivenhoe.

The town was defended by a battalion of Essex regulars and supported by almost two thousand Territorial Army inductees who had been billeted nearby. A confused battle ensued in the dark, as jittery garrison sentries mistook the reinforcements for Germans and lit up with everything they had on the stunned Territorials. At last, von Senger’s panzers came rolling up, following the sunken rail bed running into Wivenhoe.

The sudden appearance of the tanks seemed to shake the British out of their hysteria, and a battery of 2-pounders dug in east of the town opened fire on the tracks. Three Panzer Is were disabled before von Senger even learned that contact had been made. Pulling his units hurriedly back, he reformed his leading battalion to advance cross country along a sweeping 900 meter front. Silhouetted by flares from both sides, 51 panzers crashed through fences and hedges, churning fallow fields to dust as their commanders sighted on the square belfry of the town church. The enemy guns cracked again.

British artillerymen man a 2-pounder. December 3, Essex.

From his headquarters section 500 meters back on an overpass above the railway, Oberst von Senger had seen several columns of smoke and red flames bloom from the low ground just out of sight. He had radioed his company commanders for a report. The guns -- they counted eight -- were well protected behind a series of earthen berms, and were at such close range that even glancing hits were punching through the Panzer Is’ paper-thin armor.

On the other hand, the close range allowed the British only a few minutes of shooting before von Senger’s tanks were on top of them. The advance swept onward, slamming into the Essexes arrayed outside the town and pushing onward into Wivenhoe.

Wivenhoe, night of December 3.

Two hours of intense fighting ensued, as I. Panzer-Bataillon systematically cleared street after street. With the 2-pounders overrun, the British infantry had scant anti-tank weaponry -- aside from a single Boer War-vintage elephant rifle that Duff Cooper had assigned the garrison for just such an occasion. As von Senger threw his supporting Schütze troops into the attack, the British withdrew to the town center and the cover it offered. The German column battering its way down Hamilton road toward the railway station found itself stymied at the High street intersection. Several automobiles had been overturned to block the way forward, with tangles of concertina wire stretching out in front of them from sidewalk to sidewalk. A pair of Vickers machine guns sandbagged between the cars were spitting tracers down the road.

Probing the British perimeter, von Senger had found most of the defenders holed up in an area of three square blocks west of High street. He had ordered a halt while he dispatched his second battalion to disperse a counterattack from the north by a large but hesitant force of Territorials. Major Rolf Lippert, one of von Senger’s cavalry protégés, had ordered his II. Panzer-Bataillon up the Colchester road running north from Wivenhoe -- and into a wooded park where the enemy had been loitering since the start of the battle. The two forces met sooner than expected at the outskirts of the town, and the surprised tankers had started firing wildly, swerving across the park trying to run down the dark shapes that seemed to spring out of the ground itself. The startling violence of the performance quickly set the British to flight. von Senger had ordered Lippert not to pursue.

By 0145, von Senger was ready to commence the final assault on the center of Wivenhoe. Standing orders dictated that he try to obtain a surrender, though, so another hour and half elapsed as messages were traded back and forth across the lines. Finally, word arrived that the British major commanding the defense had agreed to negotiate terms at the farmhouse outside the town that von Senger was now using as a headquarters and field hospital. Another hour passed, but the officers on the battle line reported that despite continued messages, no commanding officer was forthcoming. The British were clearly stalling. The disposition and numbers of other enemy forces on the east side of the Colne still wasn’t fully clear, and von Senger couldn’t rule out the possibility that significant units had moved up from Clacton-on-Sea in the dark and were preparing to strike him from behind. Nonetheless, an all-out out fight for the now-surrounded town center would have been wasteful for both sides, and von Senger refused to consider it unless absolutely necessary. He sent word back across the lines: the defenders had fifteen minutes to surrender unconditionally. Still nothing.

Running out of options, von Senger ordered a limited attack on one side of the perimeter, aimed at taking the railway station. Two Schütze companies converged on the station from two sides supported by a four-tank platoon of Lippert’s panzers. The Essexes had clung bitterly to their positions, but were soon driven back. The Germans picking their way through the ruined station house counted 37 kettle-helmeted dead.

At last, just before 0400, Wivenhoe’s surviving defenders had surrendered. Taking the town had cost von Senger 98 killed and a surprisingly high 17 of his tanks out of action. Inquiring as to the cause, he had been relieved to hear that most of the latter losses would be recoverable. As it happened, nine of I. Bataillon’s Panzer Is had merely blundered into a series of dry irrigation ditches in their sprint toward the anti-tank guns at the start of the battle. Their vehicles stuck -- and in one case flipped -- in the line of fire, the crews had thrown open their hatches and taken for the rear.

As his Feldgendarmes marched the prisoners to the rear, von Senger drove forward to the riverside quays. There were no bridges this far downstream, but the opposite bank was lined with concrete pillboxes. Every now and then, one of them would spray a rope of bright tracers across the water at Germans who dallied too long in the open. His men were hard at work emplacing half a dozen PaK 36s along the flood wall.

The positions were at practically point-blank range for the German gunners, and the Colne was rather low on its banks, exposing great stretches of silty sand on each bank. Soon, their slender barrels were puffing orange flashes and thick cordite smoke -- even in the dark, it was almost impossible to miss. More difficult, though, was hitting for effect, as even these hastily-constructed casemates were strong enough to repel anything but a perfect strike.

German gunners suppress a British patrol sighted on the west bank of the Colne. Morning of December 4.

As the cross-river duel played out, von Weichs radioed von Senger with word that the schedule had been pushed up. The situation in the Channel was still “fluid,” he said, and although HKK had planned landings later that morning at Brightlingsea, at the mouth of the Colne, changing transport conditions had necessitated that a force of torpedo boats do the job in the dark. The force, consisting of Kondor, Seeadler and a pair of minesweepers, had passed the Colne bar at 0230, and disgorged two Pionier companies straight onto the Brightlingsea beach after finding the docks dismantled. The town had fallen quickly, he said, and the minesweepers were now towing a string of pioneer barges upriver to begin bridging work.

Around the time the barges were projected to arrive, von Weichs had called again with a complication. The torpedo boat Seeadler had managed to beach itself on one of the Colne’s treacherous sandbars, and the pioneers had frantically tried to free it before first light, only to conclude that the ship was held too firmly in the muck to have any hope. The barges were on their way after all.

By 0500, the pillboxes had been silenced, and a platoon of von Senger’s men had motored across the river in commandeered launches to complete their destruction. The minesweepers came into view at 0517, and had promptly begun construction work at the Wivenhoe quays. Working under frightfully visible carbon arc work lamps, they had set about bolting together prefabricated sections of a light-use bridge. The Colne was only 50 meters wide here, and the assembly went quickly. The bridge wouldn’t be strong enough to support von Senger’s panzers, but would at least allow him to get enough men across to secure the west bank until morning. Less than two hours later, the first German motorcycle troops crossed the Colne, followed by most of 6. Panzer’s infantry.

Kradschützen cross an improvised bridge over the Colne at Wivenhoe. Early morning of December 4.

Now, it was getting light, and the pioneers were hard at work on another bridge, just downstream of the first one, that would be able to support the weight of tanks, trucks and armored cars. The engineers hoped to have it ready by mid-afternoon.

von Senger lowered his binoculars and looked out over Wivenhoe. Several trails of sooty, brownish smoke were slowly drifting high into the air. The rumble of distant artillery reminded him that in the rest of Essex, the day’s combat was only just beginning. While the Kradschütze motorcyclists pushed westward to conduct reconnaissance, the rest of 6. Panzer-Regiment tried to get what rest it could. While the pioneers worked, the men might be able to get five or six hours of sleep. Then on they would push over the Colne and through the long night back up north toward Colchester. von Weichs wanted the battle for the city decided on December fifth. It seemed that the British were trying to make the river their final stop line in Essex, the Generalleutnant said, and a swift knockout blow to Colchester would undermine the enemy’s defenses all the way to London.

Raising Major Lippert on the radio, von Senger gave his final orders for a defensive line around Wivenhoe, then slipped into the back of his armored car for a few hours’ rest.

Last edited: