Weltkriegschaft

- Thread starter TheHyphenated1

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Hello All,

Apologies for the unplanned hiatus again. Rest assured that I am hard at work on the next installment of Weltkriegschaft, which will hopefully go up some time this weekend. Stay tuned!

TH1

How about this weekend?

Chapter III: Part XXXVII

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XXXVII

December 1, 1936

The throb of hundreds of engines filled the frigid air above the Pas-de-Calais as the dark flock of aircraft assembled. By the light of the nearly full moon, 92 Ju-52 transports and their towed gliders wheeled in great circles as their fighter escorts took off from the runways below. It was shortly after midnight, and as the last of the biplanes fought their way to altitude, the signal went out for the aerial armada to come into formation. Every pilot had executed these banks and turns dozens of times; each knew his carefully assigned place. Converging into a dark lance more than 10 kilometers long, the planes turned north.

At the tip of the lance, in a glider painted with a large white 1, Oberstleutnant Bruno Bräuer steeled himself to land the first blow of the historic invasion. Tasked with seizing the heavily-defended port of Dover intact, this was the fourth Sturmabteilung Bräuer -- successor in name to the legendary force that captured Fort Eben-Emael and two airfield assaults that Bräuer had led in France -- and was by far the largest. 736 assault pioneers composed a headquarters section and ten companies of 72 men, each one in turn made up of three three-glider platoons. Normally built to carry ten men, each DFS 230(II) glider instead bore a smaller eight-man squad and 360 kg of extra supplies. Every man was armed with an automatic weapon, the reliable and accurate MP34, a Luger pistol sidearm, a folding-variant Kampfmesser knife and a brace of storm grenades. Divided among the 92 gliders’ ready-use crates were a plethora of additional items, of variable practicality. There were 92 MG34 light machine guns (one per squad, each with 3,000 rounds of ammunition), 5,200 hand grenades (assault, defensive high-fragmentation, smoke, phosphorus, thermite and several containing an aerosolized form of capsaicin), 10 leGrW 36 light mortars (two hundred 50 mm rounds each), 10 flamethrowers, 92 Kar98k rifles, 10,000 kg of explosives (shaped, granulated, as putty and in sticks), 20 kilometers of wire and fuses, 300 spikes for gun sabotage, 5 inflatable rubber rafts, 300 liters of gasoline, 25 liters of motor oil, 12 radios, 20 sets of semaphore flags, 5 signal lights, 4 sets of block-and-tackle winches, 36 German flags, 6 British flags, 20 sets of horseshoes and a single light aircraft engine. There were 15 kilometers of telephone cable, 550 entrenchment tools, 257 various other tools (ranging from general-purpose hammers to heavy bolt cutters to special screwdrivers that could be used to disassemble the glider frames), 900 flares (red, red star, green, double green, white star, and yellow mortar), 270 maps and schematics, 3 portable alcohol-burning stoves, 2,578 tinned meal rations, 500 liters of drinking water, 5,225 caffeine tablets, 746 gas masks and 2,000 sets of one-use rubber shackles. In the medical kits (divided among ten company sanitäter), there were enough bandages to wrap around the entire circumference of Dover Harbor and enough morphine to kill every single man in Sturmabteilung Bräuer. The attack force carried 16 still cameras (half of them color), parts to assemble a gasoline-powered electric generator, 5 carbon-arc strobe lights, and a Kinarri movie camera with 8 kilometers of 16 mm film. They carried more than 40,000 leaflets printed in English, £300,000 in large notes (both for bribes and the lawful purchase of any goods somehow omitted from the near-exhaustive equipment list), 200 sets of warm clothing, roughly 5,000 bars of chocolate, 3000 kg of quick-drying cement, a violin, 3 bugles, a copy of Peterson’s Field Guide to the Birds, 15 Bibles (five Roman Catholic, nine Protestant and one Reformed), a set of Pathé loudspeakers, 95 magnetic compasses, 190 sets of binoculars, 8 apothecary’s scales, 11 blowtorches, 2 hectares of camouflage netting and 6 footballs. Weightiest among the hundreds of other entries rounding out the equipment manifest were 260,000 rounds of crated small-caliber ammunition.

For nearly five months, Sturmabteilung Bräuer had trained relentlessly, meticulously -- obsessively -- for this night. Oberst Kurt Student, overall commander of the operation, had given Bräuer full discretion over the training and preparation for the mission, spending most of his own energies on deflecting interference from superiors and ensuring that Bräuer’s every request was fulfilled.

Both men fully appreciated the consequences of failure. Three weeks after the Scholl Memorandum, Student and Bräuer had been summoned to the Berghof. In the study of his mountain chalet, the Führer had inducted them into the tiny cabal then aware of his plan to invade England. Looking almost disappointed at the equanimity with which the two officers took the news, he had handed each a copy of an infant draft of the plan called Löwengrube.

The invasion force would require three deep-water ports in the first hours: Dover, Ramsgate and Harwich. If they were taken intact, destroyers and fast transports could sprint across the Channel laden with enough men and supplies to establish a secure beachhead. If the ports were not captured, or were captured only after the docks and port machinery had been sabotaged, the Wehrmacht would have no way of getting enough men across before the Royal Navy intervened decisively. “Given the necessity of success, you should attack with not less than two thousand men per port,” Hitler said, “and that is final.”

Yet by the start of July, the Parachute and Glider school at Stendal had graduated just under a thousand men. Student and Bräuer had returned to the Berghof on the fourth to pitch their revised plan. They had evaluated reconnaissance photos for potential glider landing sites at each port, and found that none had enough open space to allow two thousand men to be inserted safely. If anything, Student warned, coordinating almost five hundred aircraft over each port -- transports, gliders and fighters -- would lead to more casualties through collisions and accidents than any enemy fire was likely to inflict. Instead, it was preferable to attack each port with less than half that number; even then, more than two thousand extra men would need to be trained, but this was within the bounds of what could be achieved. At last, Hitler had relented.

Student had been adamant that Bräuer personally lead the assault upon Dover, which he considered the most difficult mission. He had found himself hard-pressed to nominate qualified commanders for the other two forces. In the end, he had elected to widen the search outside the present cadre of Parachute/Glider officers. To lead the assault at Harwich, Student chose a highly decorated lieutenant colonel named Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke. A proven and daring leader of men both in the First World War and with a Freikorps in Russia against the Bolsheviks, Oberstleutnant Ramcke fit Student’s specifications to the letter. For the taking of Ramsgate, Student tapped a personal friend. Oberstleutnant Eugen Meindl was a pioneer-trained artilleryman whose name had come up as a possible substitute for Bräuer in leading the attack on Eben-Emael ten months earlier. Square-jawed and sardonic, with an athlete’s chest peppered with Imperial-era knightly orders, Meindl effortlessly commanded the unswerving loyalty from subordinates which Student felt was so essential in airborne operations.

On the ninth of July, Student flew to Rome for further talks with Hitler, who was on a visit there to confer with Mussolini. He traveled with the Führer back to Berchtesgaden, where he introduced him to Ramcke and Meindl. Hitler had been greatly impressed with both, and sent Student to Berlin with instructions to flesh out the operational plans with OKL staffers. There, in a room in the Hotel Adlon, Student and his commanders had spent three days poring over hundreds of personnel files to select their junior officers, glider pilots and NCOs. Student had given Bräuer alone final say over his selections, as well as plum training facilities in Berlin and on the Baltic coast -- Ramcke and Meindl would be jointly training their men at a larger camp in Saxony.

Oberstleutnant Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke (left) with Kurt Student at the Berchtesgaden train station, July 9, 1936.

Ramcke (left), Student and Major Hans Kroh (right) at the station. Kroh had just been confirmed as the reserve commander for the Dover assault.

On July fifteenth, 1,215 men had gathered near Lübeck for the start of a training program that would ultimately prove too much for nearly half of them. Six days a week the hard-driving Bräuer had drilled his men, with Sundays reserved for rest, English lessons and swimming in the icy waters of the Baltic. Bent on increasing the assault pioneers’ efficiency in close-quarters combat, Bräuer had brought in boxers, arms masters, marksmen and a Judo instructor to train them. Demolitionists taught half the men advanced explosives, while Kriegsmarine experts held a seminar on anti-sabotage operations.

To compliment the technical training, the men’s bodies had been honed with their commander’s characteristic intensity. Student, Bräuer and a clique of dietitians had conferred in the second week of July to draw up the ideal nutritional regimen for the men. Fresh vegetables, fruits, nuts and brown rice were provided in abundance -- Student managed to satisfy Bräuer’s request that the men eat nothing canned -- along with protein-rich venison, codfish and duckling. As soon became legendary in the unit, one of the captains had discovered a contraband chocolate bar in the mattress of a young Gefreiter and reported the man to Bräuer expecting him to set a 10 kilometer run as punishment. Instead, Bräuer had become so incensed that he sent the man home on the spot. “Nothing,” he had written Student, “can be allowed to impair the soldiers, whether from within or without.”

Even the relatively brief flight would sap oxygen from the assault pioneers’ blood, and Bräuer was determined that this not hamper the men’s performance. For two weeks in August, he had taken them to camp along the Austrian border for altitude training. From the deserted athletes’ village at Garmisch-Partenkirchen, site of February’s Winter Olympics, they had trained along the shoulders of Germany’s highest mountain, the Zugspitze. As doctors watched and measured, they had exercised vigorously at its summit, which closely approximated the altitude of the longest portion of the flight in the open gliders. Two collapsed and were hospitalized from heatstroke, but by August fifteenth, Bräuer was ready to make his final cuts.

He posted the names of the 735 men who would make up Sturmabteilung Bräuer, as well as those of the 20 ready alternates who would follow them to their Berlin camp for glider rehearsals. Engineers constructed a scale mockup of the landing sites, aided by continuing aerial reconnaissance over Dover. They rehearsed endlessly -- first with transports only, then with gliders; by day, then by night; empty, then weighted, and then with full men and gear. Some of them were granted special leave in September to take part in combat operations in Holland; seven alternates were called up to replace the fallen. Still they trained, Bräuer obsessively critiquing the smallest errors, until even he had few reasons to complain to Student.

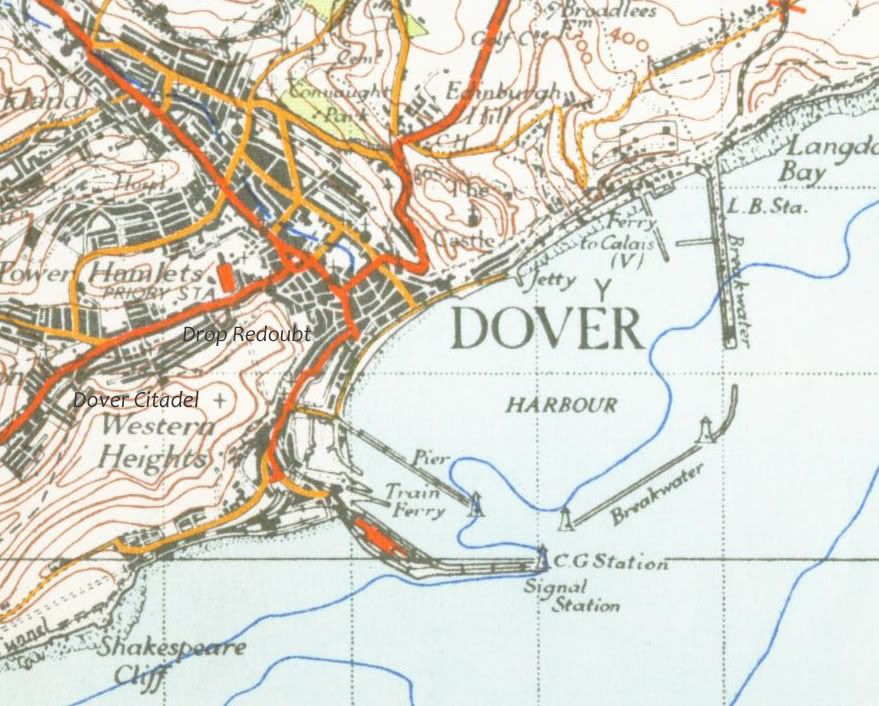

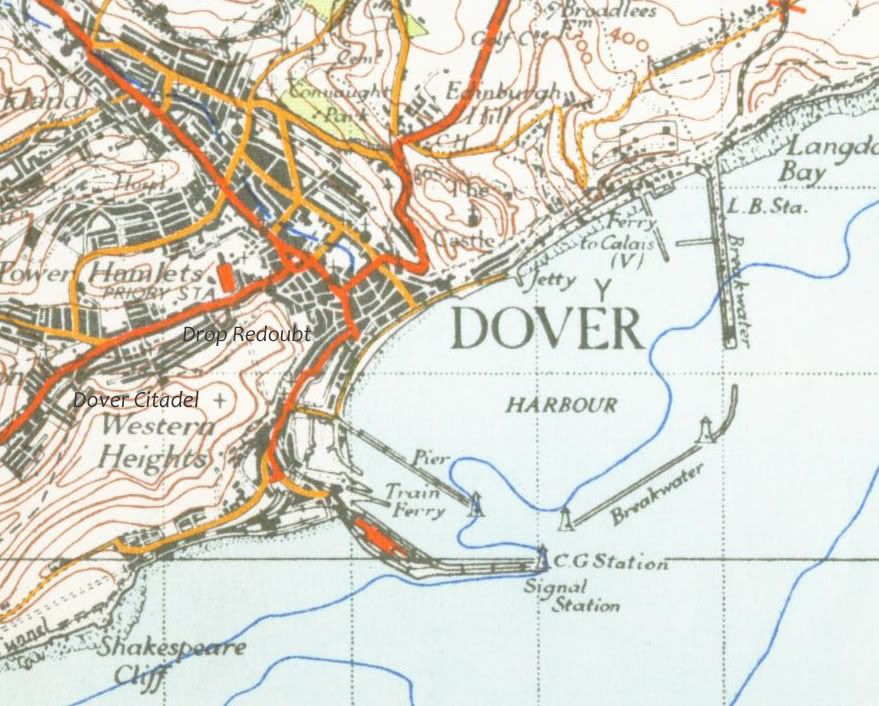

Dover from the air.

Even now, Bräuer could sense the precision in the pilots’ maneuvers as they banked slightly to the northwest, and out over the waters of the Channel. It was a breathtaking sight. Bräuer felt then, for the first time, the true enormity of the invasion. Out the small square window he could see ships -- hundreds of them, piled like cordwood in the harbor of Boulogne-sur-Mer. A forest of masts shone white in the moonlight, and Bräuer could see the luminous green wakes of torpedo boats bustling protectively far below, herding the mass of transports as they slipped out of their berths. He went to the opposite window, where he could see the bowed promontory of Cap Gris-Nez. Beyond it, another glinting fleet could be seen gathering, but the Cap itself was dark. Somewhere in that darkness were the batteries of heavy artillery that could be called upon to support Sturmabteilung Bräuer in the event of counterattack.

The lance made another turn northwest, and the Cap, the ships and the harbor swung out of view. Growing anxious without something to look at, Bräuer slipped up to the cockpit. There were only two transport-glider pairs ahead of them. The tow rope slackened slightly as the planes edged off speed. “What is it?” Bräuer whispered to the pilot.

“Some of the planes behind us have to catch up, Oberstleutnant. Nothing to worry about.”

The stark light of carbon-arc searchlights appeared in several places on the blacked-out coastline ahead. The bright beams wandered for a moment, and then began to search the seaward sky. The transports continued to slow, and the nimble shapes of biplane fighters buzzed past them and toward the source of the searchlights. Tracers drifted up from unseen emplacements, followed by the magnesium wink of airburst shells. For several minutes, the shooting drew closer, slipping gradually away to the left. At 0031, they crossed the English coast near Hastings at 3500 meters.

The plan called for the attack force to cross the coast here, more than 50 kilometers west of Dover, to disguise its true objective. They would turn to the northeast and proceed far inland, rounding Ashford and then tacking east-southeast to take Dover from the rear. As the gliders made their silent approach from an unexpected direction, the transports would continue on to Canterbury to draw off any unwanted attention.

Luftwaffe staffers at HKK had initially opposed the plan, preferring an easier direct insertion onto the wide bluffs midway between Folkestone and Dover. But this would have given the defenders at Dover ample warning -- perhaps enough to destroy the port and then mow down the assault pioneers as they crossed the open, coverless ground on the way into the city. Instead, Student and Bräuer had insisted on a much more violent and dangerous insertion that placed men straight onto Dover’s heavily fortified Western Heights.

Glider 1 and four others would land atop the works of Dover Citadel, hoping to occupy the defenders while a much larger group of gliders landed on the slopes below the batteries and further along the Heights to the northeast. These men would join in securing the Citadel and then the nearby landward-facing bastion, while another mass of gliders was landing near the so-called Drop Redoubt, whose guns covered the docks and the approaches into Dover. Meanwhile a second large group of gliders would land in the level fields north of Dover Castle, on the east side of the city, under Bräuer’s second-in-command, Major Hans Kroh. A group of Kriegsmarine engineers and demolitions men would be simultaneously inserted by U-boat and seaplane to secure the docks and inner harbor and thwart sabotage. The HKK planners had predictably balked at the plan’s sending Bräuer into the teeth of the Citadel defenses, but Student was quick to assert his mandate from the Führer. “Bräuer goes onto the Heights or not at all,” he had informed Bayerlein flatly on September thirtieth. The former lieutenant-colonel had been in no position to disagree.

Dover and its harbor. The city and docks were framed by the fortified Western Heights to the west, and Dover Castle to the east.

And so, the lance of Sturmabteilung Bräuer began to turn. They passed deeper and deeper inland, climbing in altitude as the guns of Hastings gradually faded from hearing. The Kentish countryside below was almost dark enough to be mistaken for the sea at this altitude, save for the occasional glow of a motorcar’s blacked-out headlamps winding down an unseen road. HKK’s greatest objection to the inland turn had been navigation, and now that he looked down upon English soil, Bräuer privately began to share in their worry.

“Pilot, can you see any better than I can?”

“Not a bit, Oberstleutnant,” he replied cheerfully. “But we have a clear sky, so Oberstleutnant Drewes in the lead transport can take accurate readings from the headland at Dungeness.”

“At least I hope he can.”

“Don’t even joke, Oberstleutnant. Aha! See, those tracers are coming from Ashford.”

Sure enough, spirited anti-aircraft fire was rising from an area in front of them, joined now by a pair of searchlights scissoring through the darkness. The towrope ahead slackened.

“They think we’re bombers. The fighters are going in to draw fire now, Oberstleutnant.”

The sparking, thudding battle over Ashford slowly slipped to the the right of the transports as they passed to north of it.

“That’s it,” the pilot called, “the lead plane is turning.”

Seconds later, the transport towing Glider 1 banked into a right turn -- east-southeast, and straight for Dover. As the great lance formation became bent rounding Asford, the transport-glider pairs at its tip began to level off. Far ahead, the sheen of the Channel could be seen through the cockpit window, and along the faint horizon, France.

“Altimeter 4500 meters. There’s the signal to release.” The Ju-52 waggled its wings and then resumed level flight.

The pilot pulled the tow rope release, and after a long second Bräuer felt the familiar buck and watched the transport slip upward and away out of sight. Gradually, the engine noise -- a constant companion since arriving at the French airfield three hours before -- faded, leaving only the soft whistle of wind against the glider’s skin. Finality washed over Bräuer with the realization that they were now hurtling unpowered through the air on their seventeen minute descent toward Dover.

When word had come down that the invasion had been confirmed for an autumn date, and consequently would not include landings at Ramsgate, Student had rushed to Berlin to lobby Hitler not to dissolve Sturmabteilung Meindl. The men had already been training together long enough that Meindl’s force couldn’t be broken up and integrated into Bräuer or Ramcke’s units. Holding it back as a reserve or second wave wasn’t practical, because the clearings in which the gliders would land couldn’t be reliably cleared in the dark. Even without landings at Ramsgate, Meindl’s men would still have the advantage of speed and surprise -- as well as firepower sufficient to overwhelm anything short of a direct assault by British tanks. Student envisioned them dispersing into platoons and sowing chaos and confusion on the roads between Canterbury and the coast. He knew that the British command wouldn’t commit their reserves until they had a reasonably clear picture where the Germans were landing and in what strength. Unlike Bräuer and Ramcke, who would fall into defensive postures as soon as their respective ports were secured, Meindl would be free to take the initiative and press his advantage to the fullest. Even when the British defenders realized where the German attack was falling, it would be hard to coordinate a concerted counterattack on Dover with a battalion-sized group of assault pioneers marauding far inland from the beaches. Hitler had seen the wisdom in Student’s proposal, and readily consented.

Operation Rösselsprung -- Knight’s Leap -- the glider operations were now called. The men were flown to their bases in France and Belgium and sequestered in utmost secrecy. On the twenty-sixth of November, a pallet arrived from Berlin with the stimulants for the night of the operation. “Methamphetamine!” Bräuer had fumed as the packets were examined. “What are they thinking?” After relatively mild caffeine-based stimulants had helped assault pioneers maintain combat endurance for more than a full day of fighting at Eben-Emael, the Luftwaffe had become quite taken with the effect, and commissioned several studies on the subject by the Institute for General and Defense Physiology. For the glider operations in Holland, the men had been issued a new and far more powerful agent -- tablets of an unmoderated methamphetamine powerful enough to induce convulsions in some men. Berlin had been convinced that soldiers could be kept in three days of continuous combat with the substance, but the side-effects had been disastrous. Jittery soldiers had caused accidents, shot one another by mistake, and acted recklessly under fire. Bräuer had refused its use in England, and through Student had received confirmation from higher authorities that they would be be returned to the old caffeine pills. Nonetheless, someone had pig-headedly shipped them methamphetamine, and it wasn’t until the afternoon before the operation that the milder stimulants had arrived.

They were getting close now. From what Bräuer could see of Dover through the pilot’s windscreen, there was no great alarm -- only a few pairs of searchlights swiveling around as part of the general air raid warning. Even as he watched, one of them switched off.

Bruno Bräuer was determined to profit from every one of the glider and parachute program’s hard-earned lessons. From Eben-Emael to the Grebbe Line, assault pioneers had made costly mistakes, and success in Dover would require that they learn from each of them. Among the lessons of Eben-Emael was a redoubled impetus to maintain constant pressure on the enemy throughout an assault. Bräuer had spent ten months regretting the time wasted on top of the fortress on the first morning while the radio was being repaired -- a lapse which had allowed commanders in the nearby town to organize the attack which had ultimately dislodged the Germans from their positions.

“Your advantage is shock and firepower,” he had told the men countless times in training. “He who does not allow his enemy to recover from the initial shock of assault shall emerge victorious.” Bräuer clutched the grip of his MP34. At close ranges, the men in the glider with him alone had the firepower of an entire company armed with bolt action rifles. My advantage is shock and firepower.

The glider was passing low over the rolling hills just inland from Dover, in perfect silence except for the wind against the aircraft’s skin. Bräuer looked back at the seven assault pioneers behind him in the glider. “Final approach. Positions for landing.” Each man braced himself against his seat frame. “Good luck.” The smooth, forested crest of the Western Heights came into view dead ahead. Just beyond was the landing site and the Citadel. The glider nosed up, bleeding off speed and fighting to stay above the treetops over the final seconds of the approach. They were just meters away now.

“This is going to hurt,” the pilot whispered as the glider cleared the trees. He sent the nose sharply downward, and an almost instantaneous impact jarred the aircraft. Everything in the glider jolted forward as the nose plowed a deep furrow into the icy ground, rocking back upwards and coming to a stop just a few meters from the wall of a nearby blockhouse.

“This way!” Bräuer leapt from the glider, planting Operation Löwengrube’s first German boots on England’s frost-bitten soil.

Almost before he could regain his balance, a siren began to wail at the other side of the Citadel. After just seconds, it stopped inexplicably.

“Down!” Bräuer shouted to those following him out of the glider, as he turned and tossed a storm grenade up to the blockhouse door and threw himself to the ground. Almost instantly there was a shattering bang, strangely protracted, but when Bräuer opened his eyes, the grenade was still there.

He jumped to his feet and turned toward the source of the sound. Just twenty meters away lay his worst nightmare since those first minutes atop Eben-Emael. Glider 2 had bounced off the frozen ground and smashed into the far corner of the long blockhouse. One wing had sheared off, and the glider’s crumpled belly was torn open along its entire length. Ammunition boxes and radio equipment littered the surrounding turf, and Bräuer saw the glider turn upside down, and the horizon with it.

He felt his head hit the ground sharply, and looked curiously upward at his bare right foot. He wiggled the toes. Why am I barefoot? I shouldn’t let the men see me barefoot. If they see me barefoot, they’ll think that can train out of regulation gear as well.

Bräuer’s heartbeat pounded in his head. He rolled over onto his left side. The crumpled glider brought him back with a jolt to awareness of where he was. He propped himself up on his hands. The men from a third glider were around the wreckage, trying to assist the wounded. My stupid grenade. The grenade! How could I have forgotten?

He stood on weak legs and went over to Glider 2. “How many casualties?” His voice sounded strange to himself, his hearing still reeling from the grenade’s overpressure.

A sergeant mouthed: “Pilot’s dead. Two men with compound fractures.” His breath was steaming in the cold.

“Alright. One man can tend them. I want everyone else on me.”

“Yes, Herr Oberstleutnant!”

Bräuer turned and took stock. All five gliders had now landed on the field -- fortunately there was not yet any sign of gunfire or an alarm. Glider 1’s other seven men were evidently storming the blockhouse nearest their glider, and would proceed to assault the other five in detail. Bräuer ordered the men from Glider 2 who were not badly hurt to set up a light machine gun and mow down any British soldiers who came out of the barracks blockhouses beyond the field where the gliders had landed. He took the remaining 22 men and led them at a run over the causeway that ran over a dry ditch and into the heart of the citadel.

They had crossed about halfway to the citadel’s parade ground when they blundered into a sentry rounding the corner of one of the old barracks. He had a flashlight in hand, rifle still slung over his shoulder. He stood frozen, eyes wide under the brim of his kettle helmet, gaping at the intruders who had fallen under his beam.

“Surrender immediately,” Bräuer said in English. “If you so much as speak, you will be shot.”

Without warning, the sentry flung his flashlight straight at Bräuer’s head and sprinted in the opposite direction, yelling. The flashlight missed, but as it passed out of Bräuer’s field of vision, he found the darkness ahead much deeper than it had been. The Germans fired hotly after him, but they failed to silence the man’s shouts.

Feldwebel Hürtz, one of the trupp leaders, began to run after the man, but Bräuer restrained him. Any more gunfire would prove a far more effective alarm than any man’s bellowing.

Instead, Bräuer ordered Hürtz and his men straight toward a large, low building about a hundred meters to their left. This was the citadel’s armory, and was the most vital objective for the early phase of the assault. In all likelihood it was deserted at this hour, so he ordered them, upon securing it, to set up their light machine gun in a position to rake the parade ground.

Bräuer himself would lead the remaining two truppen toward the long brick building off to their right, which contained the officers’ quarters. They set off running again down the now-floodlit lawns, encountering no further opposition, and soon stacked on each side of the building’s great stone entryway. Bräuer peered around the corner, and saw two elegant front doors. He reduced them to firewood with a single storm grenade, and the assault pioneers charged into the breach.

They fanned up the main staircase and down the narrow, darkened hallways of the old Victorian structure, the alarmed shouts of rudely awakened officers echoing from room to room.

“Keil, Peiper, on me! I’m looking for the roof.” Bräuer found a corridor leading deeper into the building. A uniformed British officer blundered into the way, but Bräuer shoved him over with all his might and shouted for the two machine gunners to keep up. They raced past bedrooms and a suite of offices, where Bräuer had to bowl over several other officers cautiously stepping out their doors. The Germans turned, made it a short way down a second long hallway, and at last came to a narrow landing where a wooden staircase ascended to a closed heavy door. Keil and Peiper trundled up behind him with their MG34. “Stay there.” Bräuer climbed the stairs and tried the door. Locked. Two rounds from his submachine gun cleanly carried away they bolt, and he swung the door open. He was on the building’s long flat roof, just as it had appeared in the reconnaissance photographs. Perfect. As he stood there, a German glider whispered over the rooftop and down toward the field beyond.

He called for Keil and Peiper, and positioned them on the parapet overlooking the building’s entrance. “If any soup-bowled heads show up down there, let them have it.”

From deep within the building, a spurt of gunfire sounded, followed by a lone shot, and then breaking glass. Bräuer raced back down the stairs. He soon found Feldwebel Kross in the library, interrogating a very red-faced Scot wearing not much more than his muttonchops.

“This is Major Brown, Oberstleutnant. Haven’t been able to get much more than spittle out of him, but apparently he’s the battery commander. What should we do?”

“Not much good, Kross,” Bräuer said. “Just make sure that he’s restrained. Where do thing stand as far as the others?”

“We’ve taken about thirty prisoners, and we’re herding them all into the basement. A couple of them tried to fight it out with pistols, but we got the better of them.”

“Good work, Kross. Now I want a team to to search every nook of this place to make sure no one is hiding out on us, and another one to round up all the radio equipment and secret papers they can find.”

“Yes, Oberstleutnant.”

“And, Kross, I want --”

The high rattle of the machine gun sounded from the rooftop. There were a few seconds’ pause, and then frantic bursts. Bräuer ran to the landing, where he found two assault pioneers firing their submachine guns through medieval-style loopholes in the building’s façade -- and then down to the foyer, where the entrance was being barricaded with a dinner table and the stunned prisoner-officers herded into the basement. Another bicker from the machine gun on the roof.

They could, of course, stay in this fortress of a building, but soon the citadel’s defenses would come fully to life, and then even this bastion would prove untenable. Shock and firepower.

“Kross!” Bräuer roared.

From somewhere high above, the sergeant answered.

“Get down here with Trupp 7!”

Kross and five subordinates soon appeared.

“Alright. Weiss and his men are to hold this building at all costs. We, on the other hand, are to have covering fire from the Trupp 9 machine gun. We’ll see if we can make it on foot back to our landing site. Once there, I want to link up with the others, seize the battery, and then relieve Trupp 9 in force.”

At Bräuer’s signal, the barricading table was moved, and the seven assault pioneers sprinted out the open doorway and down the steps. They found the lawns in front of the Officers’ Quarters to be empty at the moment, though now brightly lit. Perhaps half a dozen bodies could be seen on far side of the lawns, near one of the barracks.

The Germans pressed forward, at last spotting a group of soldiers coming out of the barracks to their left, and cut them down with submachine gun fire. They hurled a few incendiary grenades into the windows of both that barracks and the one across the lawn from the Officers’ Quarters, then dashed through the darkness back to the causeway and to the area where their gliders had landed.

Bräuer was pleased to see two Germans marching several dozen surrendered British into one of the blockhouses, and the wounded from Glider 2 receiving treatment inside Glider 1, where powerful lights had been rigged.

Leutnant Christiansen, Bräuer’s second in his own command trupp, emerged from the fuselage and saluted. “Blockhouses 1 through 4, and 6, all taken. The bastards in 5 are holding out. You may notice the extra gliders over there on the far side, Oberstleutnant,” -- Bräuer hadn’t -- “but two pilots from 1-2 got confused and set down here.”

Although Bräuer was pleased to have 16 extra men from Sturmpionier Kompanie 1’s second zug, the imprecision galled him.

“The bad news,” Christiansen continued, “is that apparently one of those gliders was carrying almost all of 1’s morphine.”

Reflecting on the fact that a quarter of their still-more-precious radios were even now strewn about his feet, reduced to scrap and tinsel, Bräuer scarcely registered the outrage. He checked his watch. They had been on the ground for fourteen minutes. It seemed like a short amount of time, but the success or failure of the whole operation would have already been decided more than a kilometer away at the docks. Bräuer winced.

Setting machine guns in place, Bräuer ordered the Blockhouse 5 door breached with a powerful shaped charge. When the smoke cleared, 56 shaken artillerymen recognized the odds and filed out with their hands raised.

From the seaward slope of the Heights, he could now hear Hauptmann Barenthin and Hauptmann Hackl’s men engaging the pillboxes on the citadel’s outer perimeter. It seemed that they had now rounded up a majority of the off-duty garrison, but there would still be at least three hundred men on watch through the night, mainly along these outer defenses, who would be ready to put up a much stiffer fight than their fellows who had been rousted from their beds.

Yet Bräuer had less than forty men here, with whom he could either assault the Citadel Battery and the warren of tunnels below, which lay to the west, or relieve the two truppen now sorely pressed to hold the Inner Citadel. Plainly, he could not do both simultaneously, yet the operation’s timeline now demanded exactly that.

“Christiansen! Send a squad with two flamethrowers and plenty of explosives. They are to seize the Battery, and then work their way down from gallery to gallery, clearing any resistance they encounter. That should soon put pressure on those perimeter emplacements. Even if we cannot kill so large a number, we can at least force them to retreat before the flames. Everyone else -- our improvised hospital excepted -- is to be in your strike force.”

The twenty-two year old lieutenant saluted. The crack of shaped Hohlladungwaffe charges echoed in the distance.

“See there across the causeway, Christiansen? That nearest barracks to the left is to be our first objective. Take it, and we’ll control the parade ground and take the pressure off Feldwebel Hürtz and his men who, as far as we know, are in the Armory. We must then rapidly storm the remaining two barracks: the one further off to the right of the causeway, and then the one which stands between the parade ground and the lawns of the Officers’ Quarters.”

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XXXVII

December 1, 1936

The throb of hundreds of engines filled the frigid air above the Pas-de-Calais as the dark flock of aircraft assembled. By the light of the nearly full moon, 92 Ju-52 transports and their towed gliders wheeled in great circles as their fighter escorts took off from the runways below. It was shortly after midnight, and as the last of the biplanes fought their way to altitude, the signal went out for the aerial armada to come into formation. Every pilot had executed these banks and turns dozens of times; each knew his carefully assigned place. Converging into a dark lance more than 10 kilometers long, the planes turned north.

At the tip of the lance, in a glider painted with a large white 1, Oberstleutnant Bruno Bräuer steeled himself to land the first blow of the historic invasion. Tasked with seizing the heavily-defended port of Dover intact, this was the fourth Sturmabteilung Bräuer -- successor in name to the legendary force that captured Fort Eben-Emael and two airfield assaults that Bräuer had led in France -- and was by far the largest. 736 assault pioneers composed a headquarters section and ten companies of 72 men, each one in turn made up of three three-glider platoons. Normally built to carry ten men, each DFS 230(II) glider instead bore a smaller eight-man squad and 360 kg of extra supplies. Every man was armed with an automatic weapon, the reliable and accurate MP34, a Luger pistol sidearm, a folding-variant Kampfmesser knife and a brace of storm grenades. Divided among the 92 gliders’ ready-use crates were a plethora of additional items, of variable practicality. There were 92 MG34 light machine guns (one per squad, each with 3,000 rounds of ammunition), 5,200 hand grenades (assault, defensive high-fragmentation, smoke, phosphorus, thermite and several containing an aerosolized form of capsaicin), 10 leGrW 36 light mortars (two hundred 50 mm rounds each), 10 flamethrowers, 92 Kar98k rifles, 10,000 kg of explosives (shaped, granulated, as putty and in sticks), 20 kilometers of wire and fuses, 300 spikes for gun sabotage, 5 inflatable rubber rafts, 300 liters of gasoline, 25 liters of motor oil, 12 radios, 20 sets of semaphore flags, 5 signal lights, 4 sets of block-and-tackle winches, 36 German flags, 6 British flags, 20 sets of horseshoes and a single light aircraft engine. There were 15 kilometers of telephone cable, 550 entrenchment tools, 257 various other tools (ranging from general-purpose hammers to heavy bolt cutters to special screwdrivers that could be used to disassemble the glider frames), 900 flares (red, red star, green, double green, white star, and yellow mortar), 270 maps and schematics, 3 portable alcohol-burning stoves, 2,578 tinned meal rations, 500 liters of drinking water, 5,225 caffeine tablets, 746 gas masks and 2,000 sets of one-use rubber shackles. In the medical kits (divided among ten company sanitäter), there were enough bandages to wrap around the entire circumference of Dover Harbor and enough morphine to kill every single man in Sturmabteilung Bräuer. The attack force carried 16 still cameras (half of them color), parts to assemble a gasoline-powered electric generator, 5 carbon-arc strobe lights, and a Kinarri movie camera with 8 kilometers of 16 mm film. They carried more than 40,000 leaflets printed in English, £300,000 in large notes (both for bribes and the lawful purchase of any goods somehow omitted from the near-exhaustive equipment list), 200 sets of warm clothing, roughly 5,000 bars of chocolate, 3000 kg of quick-drying cement, a violin, 3 bugles, a copy of Peterson’s Field Guide to the Birds, 15 Bibles (five Roman Catholic, nine Protestant and one Reformed), a set of Pathé loudspeakers, 95 magnetic compasses, 190 sets of binoculars, 8 apothecary’s scales, 11 blowtorches, 2 hectares of camouflage netting and 6 footballs. Weightiest among the hundreds of other entries rounding out the equipment manifest were 260,000 rounds of crated small-caliber ammunition.

For nearly five months, Sturmabteilung Bräuer had trained relentlessly, meticulously -- obsessively -- for this night. Oberst Kurt Student, overall commander of the operation, had given Bräuer full discretion over the training and preparation for the mission, spending most of his own energies on deflecting interference from superiors and ensuring that Bräuer’s every request was fulfilled.

Both men fully appreciated the consequences of failure. Three weeks after the Scholl Memorandum, Student and Bräuer had been summoned to the Berghof. In the study of his mountain chalet, the Führer had inducted them into the tiny cabal then aware of his plan to invade England. Looking almost disappointed at the equanimity with which the two officers took the news, he had handed each a copy of an infant draft of the plan called Löwengrube.

The invasion force would require three deep-water ports in the first hours: Dover, Ramsgate and Harwich. If they were taken intact, destroyers and fast transports could sprint across the Channel laden with enough men and supplies to establish a secure beachhead. If the ports were not captured, or were captured only after the docks and port machinery had been sabotaged, the Wehrmacht would have no way of getting enough men across before the Royal Navy intervened decisively. “Given the necessity of success, you should attack with not less than two thousand men per port,” Hitler said, “and that is final.”

Yet by the start of July, the Parachute and Glider school at Stendal had graduated just under a thousand men. Student and Bräuer had returned to the Berghof on the fourth to pitch their revised plan. They had evaluated reconnaissance photos for potential glider landing sites at each port, and found that none had enough open space to allow two thousand men to be inserted safely. If anything, Student warned, coordinating almost five hundred aircraft over each port -- transports, gliders and fighters -- would lead to more casualties through collisions and accidents than any enemy fire was likely to inflict. Instead, it was preferable to attack each port with less than half that number; even then, more than two thousand extra men would need to be trained, but this was within the bounds of what could be achieved. At last, Hitler had relented.

Student had been adamant that Bräuer personally lead the assault upon Dover, which he considered the most difficult mission. He had found himself hard-pressed to nominate qualified commanders for the other two forces. In the end, he had elected to widen the search outside the present cadre of Parachute/Glider officers. To lead the assault at Harwich, Student chose a highly decorated lieutenant colonel named Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke. A proven and daring leader of men both in the First World War and with a Freikorps in Russia against the Bolsheviks, Oberstleutnant Ramcke fit Student’s specifications to the letter. For the taking of Ramsgate, Student tapped a personal friend. Oberstleutnant Eugen Meindl was a pioneer-trained artilleryman whose name had come up as a possible substitute for Bräuer in leading the attack on Eben-Emael ten months earlier. Square-jawed and sardonic, with an athlete’s chest peppered with Imperial-era knightly orders, Meindl effortlessly commanded the unswerving loyalty from subordinates which Student felt was so essential in airborne operations.

On the ninth of July, Student flew to Rome for further talks with Hitler, who was on a visit there to confer with Mussolini. He traveled with the Führer back to Berchtesgaden, where he introduced him to Ramcke and Meindl. Hitler had been greatly impressed with both, and sent Student to Berlin with instructions to flesh out the operational plans with OKL staffers. There, in a room in the Hotel Adlon, Student and his commanders had spent three days poring over hundreds of personnel files to select their junior officers, glider pilots and NCOs. Student had given Bräuer alone final say over his selections, as well as plum training facilities in Berlin and on the Baltic coast -- Ramcke and Meindl would be jointly training their men at a larger camp in Saxony.

Oberstleutnant Hermann-Bernhard Ramcke (left) with Kurt Student at the Berchtesgaden train station, July 9, 1936.

Ramcke (left), Student and Major Hans Kroh (right) at the station. Kroh had just been confirmed as the reserve commander for the Dover assault.

On July fifteenth, 1,215 men had gathered near Lübeck for the start of a training program that would ultimately prove too much for nearly half of them. Six days a week the hard-driving Bräuer had drilled his men, with Sundays reserved for rest, English lessons and swimming in the icy waters of the Baltic. Bent on increasing the assault pioneers’ efficiency in close-quarters combat, Bräuer had brought in boxers, arms masters, marksmen and a Judo instructor to train them. Demolitionists taught half the men advanced explosives, while Kriegsmarine experts held a seminar on anti-sabotage operations.

To compliment the technical training, the men’s bodies had been honed with their commander’s characteristic intensity. Student, Bräuer and a clique of dietitians had conferred in the second week of July to draw up the ideal nutritional regimen for the men. Fresh vegetables, fruits, nuts and brown rice were provided in abundance -- Student managed to satisfy Bräuer’s request that the men eat nothing canned -- along with protein-rich venison, codfish and duckling. As soon became legendary in the unit, one of the captains had discovered a contraband chocolate bar in the mattress of a young Gefreiter and reported the man to Bräuer expecting him to set a 10 kilometer run as punishment. Instead, Bräuer had become so incensed that he sent the man home on the spot. “Nothing,” he had written Student, “can be allowed to impair the soldiers, whether from within or without.”

Even the relatively brief flight would sap oxygen from the assault pioneers’ blood, and Bräuer was determined that this not hamper the men’s performance. For two weeks in August, he had taken them to camp along the Austrian border for altitude training. From the deserted athletes’ village at Garmisch-Partenkirchen, site of February’s Winter Olympics, they had trained along the shoulders of Germany’s highest mountain, the Zugspitze. As doctors watched and measured, they had exercised vigorously at its summit, which closely approximated the altitude of the longest portion of the flight in the open gliders. Two collapsed and were hospitalized from heatstroke, but by August fifteenth, Bräuer was ready to make his final cuts.

He posted the names of the 735 men who would make up Sturmabteilung Bräuer, as well as those of the 20 ready alternates who would follow them to their Berlin camp for glider rehearsals. Engineers constructed a scale mockup of the landing sites, aided by continuing aerial reconnaissance over Dover. They rehearsed endlessly -- first with transports only, then with gliders; by day, then by night; empty, then weighted, and then with full men and gear. Some of them were granted special leave in September to take part in combat operations in Holland; seven alternates were called up to replace the fallen. Still they trained, Bräuer obsessively critiquing the smallest errors, until even he had few reasons to complain to Student.

Dover from the air.

Even now, Bräuer could sense the precision in the pilots’ maneuvers as they banked slightly to the northwest, and out over the waters of the Channel. It was a breathtaking sight. Bräuer felt then, for the first time, the true enormity of the invasion. Out the small square window he could see ships -- hundreds of them, piled like cordwood in the harbor of Boulogne-sur-Mer. A forest of masts shone white in the moonlight, and Bräuer could see the luminous green wakes of torpedo boats bustling protectively far below, herding the mass of transports as they slipped out of their berths. He went to the opposite window, where he could see the bowed promontory of Cap Gris-Nez. Beyond it, another glinting fleet could be seen gathering, but the Cap itself was dark. Somewhere in that darkness were the batteries of heavy artillery that could be called upon to support Sturmabteilung Bräuer in the event of counterattack.

The lance made another turn northwest, and the Cap, the ships and the harbor swung out of view. Growing anxious without something to look at, Bräuer slipped up to the cockpit. There were only two transport-glider pairs ahead of them. The tow rope slackened slightly as the planes edged off speed. “What is it?” Bräuer whispered to the pilot.

“Some of the planes behind us have to catch up, Oberstleutnant. Nothing to worry about.”

The stark light of carbon-arc searchlights appeared in several places on the blacked-out coastline ahead. The bright beams wandered for a moment, and then began to search the seaward sky. The transports continued to slow, and the nimble shapes of biplane fighters buzzed past them and toward the source of the searchlights. Tracers drifted up from unseen emplacements, followed by the magnesium wink of airburst shells. For several minutes, the shooting drew closer, slipping gradually away to the left. At 0031, they crossed the English coast near Hastings at 3500 meters.

The plan called for the attack force to cross the coast here, more than 50 kilometers west of Dover, to disguise its true objective. They would turn to the northeast and proceed far inland, rounding Ashford and then tacking east-southeast to take Dover from the rear. As the gliders made their silent approach from an unexpected direction, the transports would continue on to Canterbury to draw off any unwanted attention.

Luftwaffe staffers at HKK had initially opposed the plan, preferring an easier direct insertion onto the wide bluffs midway between Folkestone and Dover. But this would have given the defenders at Dover ample warning -- perhaps enough to destroy the port and then mow down the assault pioneers as they crossed the open, coverless ground on the way into the city. Instead, Student and Bräuer had insisted on a much more violent and dangerous insertion that placed men straight onto Dover’s heavily fortified Western Heights.

Glider 1 and four others would land atop the works of Dover Citadel, hoping to occupy the defenders while a much larger group of gliders landed on the slopes below the batteries and further along the Heights to the northeast. These men would join in securing the Citadel and then the nearby landward-facing bastion, while another mass of gliders was landing near the so-called Drop Redoubt, whose guns covered the docks and the approaches into Dover. Meanwhile a second large group of gliders would land in the level fields north of Dover Castle, on the east side of the city, under Bräuer’s second-in-command, Major Hans Kroh. A group of Kriegsmarine engineers and demolitions men would be simultaneously inserted by U-boat and seaplane to secure the docks and inner harbor and thwart sabotage. The HKK planners had predictably balked at the plan’s sending Bräuer into the teeth of the Citadel defenses, but Student was quick to assert his mandate from the Führer. “Bräuer goes onto the Heights or not at all,” he had informed Bayerlein flatly on September thirtieth. The former lieutenant-colonel had been in no position to disagree.

Dover and its harbor. The city and docks were framed by the fortified Western Heights to the west, and Dover Castle to the east.

And so, the lance of Sturmabteilung Bräuer began to turn. They passed deeper and deeper inland, climbing in altitude as the guns of Hastings gradually faded from hearing. The Kentish countryside below was almost dark enough to be mistaken for the sea at this altitude, save for the occasional glow of a motorcar’s blacked-out headlamps winding down an unseen road. HKK’s greatest objection to the inland turn had been navigation, and now that he looked down upon English soil, Bräuer privately began to share in their worry.

“Pilot, can you see any better than I can?”

“Not a bit, Oberstleutnant,” he replied cheerfully. “But we have a clear sky, so Oberstleutnant Drewes in the lead transport can take accurate readings from the headland at Dungeness.”

“At least I hope he can.”

“Don’t even joke, Oberstleutnant. Aha! See, those tracers are coming from Ashford.”

Sure enough, spirited anti-aircraft fire was rising from an area in front of them, joined now by a pair of searchlights scissoring through the darkness. The towrope ahead slackened.

“They think we’re bombers. The fighters are going in to draw fire now, Oberstleutnant.”

The sparking, thudding battle over Ashford slowly slipped to the the right of the transports as they passed to north of it.

“That’s it,” the pilot called, “the lead plane is turning.”

Seconds later, the transport towing Glider 1 banked into a right turn -- east-southeast, and straight for Dover. As the great lance formation became bent rounding Asford, the transport-glider pairs at its tip began to level off. Far ahead, the sheen of the Channel could be seen through the cockpit window, and along the faint horizon, France.

“Altimeter 4500 meters. There’s the signal to release.” The Ju-52 waggled its wings and then resumed level flight.

The pilot pulled the tow rope release, and after a long second Bräuer felt the familiar buck and watched the transport slip upward and away out of sight. Gradually, the engine noise -- a constant companion since arriving at the French airfield three hours before -- faded, leaving only the soft whistle of wind against the glider’s skin. Finality washed over Bräuer with the realization that they were now hurtling unpowered through the air on their seventeen minute descent toward Dover.

When word had come down that the invasion had been confirmed for an autumn date, and consequently would not include landings at Ramsgate, Student had rushed to Berlin to lobby Hitler not to dissolve Sturmabteilung Meindl. The men had already been training together long enough that Meindl’s force couldn’t be broken up and integrated into Bräuer or Ramcke’s units. Holding it back as a reserve or second wave wasn’t practical, because the clearings in which the gliders would land couldn’t be reliably cleared in the dark. Even without landings at Ramsgate, Meindl’s men would still have the advantage of speed and surprise -- as well as firepower sufficient to overwhelm anything short of a direct assault by British tanks. Student envisioned them dispersing into platoons and sowing chaos and confusion on the roads between Canterbury and the coast. He knew that the British command wouldn’t commit their reserves until they had a reasonably clear picture where the Germans were landing and in what strength. Unlike Bräuer and Ramcke, who would fall into defensive postures as soon as their respective ports were secured, Meindl would be free to take the initiative and press his advantage to the fullest. Even when the British defenders realized where the German attack was falling, it would be hard to coordinate a concerted counterattack on Dover with a battalion-sized group of assault pioneers marauding far inland from the beaches. Hitler had seen the wisdom in Student’s proposal, and readily consented.

Operation Rösselsprung -- Knight’s Leap -- the glider operations were now called. The men were flown to their bases in France and Belgium and sequestered in utmost secrecy. On the twenty-sixth of November, a pallet arrived from Berlin with the stimulants for the night of the operation. “Methamphetamine!” Bräuer had fumed as the packets were examined. “What are they thinking?” After relatively mild caffeine-based stimulants had helped assault pioneers maintain combat endurance for more than a full day of fighting at Eben-Emael, the Luftwaffe had become quite taken with the effect, and commissioned several studies on the subject by the Institute for General and Defense Physiology. For the glider operations in Holland, the men had been issued a new and far more powerful agent -- tablets of an unmoderated methamphetamine powerful enough to induce convulsions in some men. Berlin had been convinced that soldiers could be kept in three days of continuous combat with the substance, but the side-effects had been disastrous. Jittery soldiers had caused accidents, shot one another by mistake, and acted recklessly under fire. Bräuer had refused its use in England, and through Student had received confirmation from higher authorities that they would be be returned to the old caffeine pills. Nonetheless, someone had pig-headedly shipped them methamphetamine, and it wasn’t until the afternoon before the operation that the milder stimulants had arrived.

They were getting close now. From what Bräuer could see of Dover through the pilot’s windscreen, there was no great alarm -- only a few pairs of searchlights swiveling around as part of the general air raid warning. Even as he watched, one of them switched off.

Bruno Bräuer was determined to profit from every one of the glider and parachute program’s hard-earned lessons. From Eben-Emael to the Grebbe Line, assault pioneers had made costly mistakes, and success in Dover would require that they learn from each of them. Among the lessons of Eben-Emael was a redoubled impetus to maintain constant pressure on the enemy throughout an assault. Bräuer had spent ten months regretting the time wasted on top of the fortress on the first morning while the radio was being repaired -- a lapse which had allowed commanders in the nearby town to organize the attack which had ultimately dislodged the Germans from their positions.

“Your advantage is shock and firepower,” he had told the men countless times in training. “He who does not allow his enemy to recover from the initial shock of assault shall emerge victorious.” Bräuer clutched the grip of his MP34. At close ranges, the men in the glider with him alone had the firepower of an entire company armed with bolt action rifles. My advantage is shock and firepower.

The glider was passing low over the rolling hills just inland from Dover, in perfect silence except for the wind against the aircraft’s skin. Bräuer looked back at the seven assault pioneers behind him in the glider. “Final approach. Positions for landing.” Each man braced himself against his seat frame. “Good luck.” The smooth, forested crest of the Western Heights came into view dead ahead. Just beyond was the landing site and the Citadel. The glider nosed up, bleeding off speed and fighting to stay above the treetops over the final seconds of the approach. They were just meters away now.

“This is going to hurt,” the pilot whispered as the glider cleared the trees. He sent the nose sharply downward, and an almost instantaneous impact jarred the aircraft. Everything in the glider jolted forward as the nose plowed a deep furrow into the icy ground, rocking back upwards and coming to a stop just a few meters from the wall of a nearby blockhouse.

“This way!” Bräuer leapt from the glider, planting Operation Löwengrube’s first German boots on England’s frost-bitten soil.

Almost before he could regain his balance, a siren began to wail at the other side of the Citadel. After just seconds, it stopped inexplicably.

“Down!” Bräuer shouted to those following him out of the glider, as he turned and tossed a storm grenade up to the blockhouse door and threw himself to the ground. Almost instantly there was a shattering bang, strangely protracted, but when Bräuer opened his eyes, the grenade was still there.

He jumped to his feet and turned toward the source of the sound. Just twenty meters away lay his worst nightmare since those first minutes atop Eben-Emael. Glider 2 had bounced off the frozen ground and smashed into the far corner of the long blockhouse. One wing had sheared off, and the glider’s crumpled belly was torn open along its entire length. Ammunition boxes and radio equipment littered the surrounding turf, and Bräuer saw the glider turn upside down, and the horizon with it.

He felt his head hit the ground sharply, and looked curiously upward at his bare right foot. He wiggled the toes. Why am I barefoot? I shouldn’t let the men see me barefoot. If they see me barefoot, they’ll think that can train out of regulation gear as well.

Bräuer’s heartbeat pounded in his head. He rolled over onto his left side. The crumpled glider brought him back with a jolt to awareness of where he was. He propped himself up on his hands. The men from a third glider were around the wreckage, trying to assist the wounded. My stupid grenade. The grenade! How could I have forgotten?

He stood on weak legs and went over to Glider 2. “How many casualties?” His voice sounded strange to himself, his hearing still reeling from the grenade’s overpressure.

A sergeant mouthed: “Pilot’s dead. Two men with compound fractures.” His breath was steaming in the cold.

“Alright. One man can tend them. I want everyone else on me.”

“Yes, Herr Oberstleutnant!”

Bräuer turned and took stock. All five gliders had now landed on the field -- fortunately there was not yet any sign of gunfire or an alarm. Glider 1’s other seven men were evidently storming the blockhouse nearest their glider, and would proceed to assault the other five in detail. Bräuer ordered the men from Glider 2 who were not badly hurt to set up a light machine gun and mow down any British soldiers who came out of the barracks blockhouses beyond the field where the gliders had landed. He took the remaining 22 men and led them at a run over the causeway that ran over a dry ditch and into the heart of the citadel.

They had crossed about halfway to the citadel’s parade ground when they blundered into a sentry rounding the corner of one of the old barracks. He had a flashlight in hand, rifle still slung over his shoulder. He stood frozen, eyes wide under the brim of his kettle helmet, gaping at the intruders who had fallen under his beam.

“Surrender immediately,” Bräuer said in English. “If you so much as speak, you will be shot.”

Without warning, the sentry flung his flashlight straight at Bräuer’s head and sprinted in the opposite direction, yelling. The flashlight missed, but as it passed out of Bräuer’s field of vision, he found the darkness ahead much deeper than it had been. The Germans fired hotly after him, but they failed to silence the man’s shouts.

Feldwebel Hürtz, one of the trupp leaders, began to run after the man, but Bräuer restrained him. Any more gunfire would prove a far more effective alarm than any man’s bellowing.

Instead, Bräuer ordered Hürtz and his men straight toward a large, low building about a hundred meters to their left. This was the citadel’s armory, and was the most vital objective for the early phase of the assault. In all likelihood it was deserted at this hour, so he ordered them, upon securing it, to set up their light machine gun in a position to rake the parade ground.

Bräuer himself would lead the remaining two truppen toward the long brick building off to their right, which contained the officers’ quarters. They set off running again down the now-floodlit lawns, encountering no further opposition, and soon stacked on each side of the building’s great stone entryway. Bräuer peered around the corner, and saw two elegant front doors. He reduced them to firewood with a single storm grenade, and the assault pioneers charged into the breach.

They fanned up the main staircase and down the narrow, darkened hallways of the old Victorian structure, the alarmed shouts of rudely awakened officers echoing from room to room.

“Keil, Peiper, on me! I’m looking for the roof.” Bräuer found a corridor leading deeper into the building. A uniformed British officer blundered into the way, but Bräuer shoved him over with all his might and shouted for the two machine gunners to keep up. They raced past bedrooms and a suite of offices, where Bräuer had to bowl over several other officers cautiously stepping out their doors. The Germans turned, made it a short way down a second long hallway, and at last came to a narrow landing where a wooden staircase ascended to a closed heavy door. Keil and Peiper trundled up behind him with their MG34. “Stay there.” Bräuer climbed the stairs and tried the door. Locked. Two rounds from his submachine gun cleanly carried away they bolt, and he swung the door open. He was on the building’s long flat roof, just as it had appeared in the reconnaissance photographs. Perfect. As he stood there, a German glider whispered over the rooftop and down toward the field beyond.

He called for Keil and Peiper, and positioned them on the parapet overlooking the building’s entrance. “If any soup-bowled heads show up down there, let them have it.”

From deep within the building, a spurt of gunfire sounded, followed by a lone shot, and then breaking glass. Bräuer raced back down the stairs. He soon found Feldwebel Kross in the library, interrogating a very red-faced Scot wearing not much more than his muttonchops.

“This is Major Brown, Oberstleutnant. Haven’t been able to get much more than spittle out of him, but apparently he’s the battery commander. What should we do?”

“Not much good, Kross,” Bräuer said. “Just make sure that he’s restrained. Where do thing stand as far as the others?”

“We’ve taken about thirty prisoners, and we’re herding them all into the basement. A couple of them tried to fight it out with pistols, but we got the better of them.”

“Good work, Kross. Now I want a team to to search every nook of this place to make sure no one is hiding out on us, and another one to round up all the radio equipment and secret papers they can find.”

“Yes, Oberstleutnant.”

“And, Kross, I want --”

The high rattle of the machine gun sounded from the rooftop. There were a few seconds’ pause, and then frantic bursts. Bräuer ran to the landing, where he found two assault pioneers firing their submachine guns through medieval-style loopholes in the building’s façade -- and then down to the foyer, where the entrance was being barricaded with a dinner table and the stunned prisoner-officers herded into the basement. Another bicker from the machine gun on the roof.

They could, of course, stay in this fortress of a building, but soon the citadel’s defenses would come fully to life, and then even this bastion would prove untenable. Shock and firepower.

“Kross!” Bräuer roared.

From somewhere high above, the sergeant answered.

“Get down here with Trupp 7!”

Kross and five subordinates soon appeared.

“Alright. Weiss and his men are to hold this building at all costs. We, on the other hand, are to have covering fire from the Trupp 9 machine gun. We’ll see if we can make it on foot back to our landing site. Once there, I want to link up with the others, seize the battery, and then relieve Trupp 9 in force.”

At Bräuer’s signal, the barricading table was moved, and the seven assault pioneers sprinted out the open doorway and down the steps. They found the lawns in front of the Officers’ Quarters to be empty at the moment, though now brightly lit. Perhaps half a dozen bodies could be seen on far side of the lawns, near one of the barracks.

The Germans pressed forward, at last spotting a group of soldiers coming out of the barracks to their left, and cut them down with submachine gun fire. They hurled a few incendiary grenades into the windows of both that barracks and the one across the lawn from the Officers’ Quarters, then dashed through the darkness back to the causeway and to the area where their gliders had landed.

Bräuer was pleased to see two Germans marching several dozen surrendered British into one of the blockhouses, and the wounded from Glider 2 receiving treatment inside Glider 1, where powerful lights had been rigged.

Leutnant Christiansen, Bräuer’s second in his own command trupp, emerged from the fuselage and saluted. “Blockhouses 1 through 4, and 6, all taken. The bastards in 5 are holding out. You may notice the extra gliders over there on the far side, Oberstleutnant,” -- Bräuer hadn’t -- “but two pilots from 1-2 got confused and set down here.”

Although Bräuer was pleased to have 16 extra men from Sturmpionier Kompanie 1’s second zug, the imprecision galled him.

“The bad news,” Christiansen continued, “is that apparently one of those gliders was carrying almost all of 1’s morphine.”

Reflecting on the fact that a quarter of their still-more-precious radios were even now strewn about his feet, reduced to scrap and tinsel, Bräuer scarcely registered the outrage. He checked his watch. They had been on the ground for fourteen minutes. It seemed like a short amount of time, but the success or failure of the whole operation would have already been decided more than a kilometer away at the docks. Bräuer winced.

Setting machine guns in place, Bräuer ordered the Blockhouse 5 door breached with a powerful shaped charge. When the smoke cleared, 56 shaken artillerymen recognized the odds and filed out with their hands raised.

From the seaward slope of the Heights, he could now hear Hauptmann Barenthin and Hauptmann Hackl’s men engaging the pillboxes on the citadel’s outer perimeter. It seemed that they had now rounded up a majority of the off-duty garrison, but there would still be at least three hundred men on watch through the night, mainly along these outer defenses, who would be ready to put up a much stiffer fight than their fellows who had been rousted from their beds.

Yet Bräuer had less than forty men here, with whom he could either assault the Citadel Battery and the warren of tunnels below, which lay to the west, or relieve the two truppen now sorely pressed to hold the Inner Citadel. Plainly, he could not do both simultaneously, yet the operation’s timeline now demanded exactly that.

“Christiansen! Send a squad with two flamethrowers and plenty of explosives. They are to seize the Battery, and then work their way down from gallery to gallery, clearing any resistance they encounter. That should soon put pressure on those perimeter emplacements. Even if we cannot kill so large a number, we can at least force them to retreat before the flames. Everyone else -- our improvised hospital excepted -- is to be in your strike force.”

The twenty-two year old lieutenant saluted. The crack of shaped Hohlladungwaffe charges echoed in the distance.

“See there across the causeway, Christiansen? That nearest barracks to the left is to be our first objective. Take it, and we’ll control the parade ground and take the pressure off Feldwebel Hürtz and his men who, as far as we know, are in the Armory. We must then rapidly storm the remaining two barracks: the one further off to the right of the causeway, and then the one which stands between the parade ground and the lawns of the Officers’ Quarters.”

Last edited:

Chapter III: Part XXXVII

The attack was soon begun. The assault pioneers stormed across the causeway but soon found themselves pinned down by a Lewis machine gun that had been set up in the window of the far barracks, throwing up tall plumes of frosty soil as the hissing tracers lanced into the darkness. Bräuer was on his back, trying to keep down while peering over a hummock to get a better view of where the fire was coming from. He heard, rather than saw, the bullets crack into the bodies of two of his men, who went down hard.

He rolled over and caught the eye of one of the trupp sharpshooters. His hands flashed quickly. Second floor. First window on the right.

The sharp pop of a Kar98k cut above the crackle of submachine gun fire, and Bräuer saw the head behind the British gun knocked forcefully out of sight.

Christiansen ordered the men up again, and quickly reached his objective barracks, easily suppressing the few artillerymen who dared to take potshots at them from across the parade ground with their service rifles. Meanwhile, Bräuer led one of the machine gun teams bulling through the back door of the righthand barracks, and straight into a hallway where about twenty British soldiers were lining up in good order, donning their helmets under the command of a sergeant.

Four minutes later, they and 67 others filed out the barracks’ main entrance single file with their hands in the air, the MG34 prodding behind them. Shock and firepower.

The lawns were now strewn with Keil and Peiper’s victims, laid out in heaps that suggested a series of failed counterattacks from the far side of the barracks that had the Lewis gun. It soon became clear that this was the only source of continuing resistance in the Inner Citadel, when word arrived that Hürtz and his men had successfully overpowered the Armory’s defenders.

The barracks was of little tactical value, and further casualties could have grave consequences, so Bräuer ordered machine guns brought up. If anyone appeared in the windows, they were to be shot. Other than this, though, no further steps would be taken to subdue the building’s occupants. The assault had to be pressed elsewhere.

Bräuer detached a squad with shaped charges to knock out a particularly quarrelsome machine gun nest just downslope, and another, under Christiansen, to reinforce the flamethrower men who were hopefully now working their way down through the tunnels and galleries of the Citadel’s outer defenses. The rest of the pioneers established a perimeter, and Bräuer returned to the roof of the Officers’ Quarters to survey what he could. On arriving, he congratulated Keil and Peiper on their good shooting -- both men were ankle-deep in spent brass shell-casings -- and looked over the parapet with his binoculars.

Fortunately, the gliders immediately downslope from the Heights appeared to have landed in fairly good order, and in the distance, the towering Norman silhouette of Dover Castle was painted by the magenta glow of three red star flares -- Major Kroh’s signal that the keep had been taken. Looking down and to the right, the port appeared to be intact, from what little of it he could see, but Kapitänleutnant Urich’s double greens were nowhere in sight.

Just eastward along the Heights, tongues of red flame were lapping from what was surely the ruined casemates of the Detached Bastion. Assault pioneers from that battle -- they would be Hauptmann Ludebrecht’s Sturmpionier Kompanie 3 -- could now be seen approaching the causeway on the eastern side of the Inner Citadel, holding their submachine guns in the air to clearly identify themselves to the nervous men on Bräuer’s perimeter.

He came downstairs to meet with Ludebrecht. The captain was to command, Bräuer said, an urgent thrust down to the docks to establish communications with Kapitänleutnant Urich and his Kriegsmarine demolitions men, and if they were either absent or had been defeated, secure the port against sabotage and await further instructions. It was about a kilometer’s march, and Ludebrecht set off at once.

In the meanwhile, Bräuer set a team of radiomen trying to salvage something workable from the crash of Glider 2. This was one night when he could not afford to be deaf and mute.

Shortly after 0200, word began to reach Bräuer that things were going badly at the Drop Redoubt. Kompanie 4 and Kompanie 5, tasked with taking this bastion directly overlooking the docks, had suffered heavy casualties assaulting up the northeastern slopes of the Heights. As the men of Hackl’s Kompanie 2 entered the Inner Citadel, Bräuer ordered them to prepare to join in the assault.

Finally: two green flares from above the docks, followed by a signal lamp from the lower part of the Heights. The demolitions men had chased away the police and succeeded in defusing the explosives wired to the docks. They had been radioing Bräuer’s headquarters section in vain for almost an hour. Ludebrecht was now wondering what to do.

Bräuer attached him to the now four-company assault on the Drop Redoubt, under overall command of Major Heilmann. Once this objective was secured, they had only to hold on until morning. In all, thought Bräuer, Operation Rösselsprung was being executed with astounding precision.

The radiomen at last returned to Bräuer’s rooftop perch with a working set. He immediately raised Heilmann, who had set up a headquarters and field hospital at Dover Priory railway station, just inland and downslope from the Heights. “Major, I have Kompanie 3 on the way to join you. When can you resume the assault?”

“Perhaps by 0240, Oberstleutnant. We have sustained heavy casualties in our first assault -- 21 killed and 20 wounded. Both of our doctors are killed.”

“I’ll send you morphine with Kompanie 2. What else do you need?”

“We have everything else, Oberstleutnant.”

“Then launch the assault at 0240. Get some mortar fire on them in the meanwhile.”

“Yes, Herr Oberstleutnant!”

Bräuer hung up the radiotelephone. “Get me that Major Brown person. I want to question him myself.”

One Gefreiter hurried down the stairs in search of the belligerent prisoner. Meanwhile, Bräuer made his first radio report to Student and his staff at their headquarters on the Cap: all principal objectives taken except the Drop Redoubt, with most of the force intact, and British resistance disorganized.

Several minutes later, Bräuer heard the boots of several soldiers tramp up the wooden staircase and onto the roof’s slate pavers. “Major Brown, what have you to say?” Silence. He turned, and saw two of his sergeants supporting Leutnant Christiansen, whose foot and ankle were thickly bandaged.

Christiansen saluted. “The Citadel Battery is ours, Oberstleutnant. We’re backing them up against the southern magazine, about 200 meters down the tunnels. Could be a hundred of them or more still down there -- I don’t know.”

“Good. Don’t let up.” As Bräuer dismissed him, he began to feel his own helplessness as the battle entered its next phase. Over the next half hour, he saw to consolidating the German positions in the Citadel, emplacing machine guns along the entire perimeter of its works, and unloading supplies from the exposed gliders. Still, sporadic fire harried them from the barracks opposite the Officers’ Quarters, and Keil and Peiper couldn’t seem to suppress them fast enough. The men couldn’t cross the lawns openly, and they were wasting an inordinate amount of ammunition just keeping the defenders’ heads down.

At last, Bräuer had had enough. Wanting his attention free to oversee the assault on the Drop Redoubt, he ordered the barracks taken down. 100 kg of PETN was placed in holes dug around each of the building’s four corners, and TNT and detonator wire run around its partially-exposed foundations.