Note to Readers: The following is the first post of a single update that will be released in several parts as time permits. These parts are not intended to be "stand-alone" as such, and will be unified into a single series of consecutive posts once all have been released. The post breaks are based not on pacing, but the characters-per-post limit of the board.

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XXXIX

December 1, 1936

Dark plumes of smoke rose over Dover, as Major Hans Kroh prepared to set out just before sunset. British heavy artillery had started several fires in the city, and a cluster of naval fuel-storage tanks was burning along the eastern side of the docks. After loading the last of their explosives, 67 men of Sturmpionier Kompanie 8 packed into seven British lorries and set off from just below the Dover Castle. They passed the eastern pickets, and trundled down A258 into the blustery gray evening with headlamps off. Enemy soldiers had been sighted in the fields beyond the Castle not long before, and assault pioneers hung from the running boards, ready to dismount and engage if they encountered any. But as the A258 curved north on its way to join the A2 highway to Canterbury, no resistance materialized, and the convoy picked up speed.

Kroh had been an officer of police in Landespolizeigruppe “General Göring” -- and when Göring’s Luftwaffe “came out” in October of 1935, Kroh had been transferred into its service. In the wake of Eben-Emael, he had entered Kurt Student’s Parachute/Glider school at Stendal, and won the Iron Cross 1st Class as a company commander in the assault on the Brest aerodrome. These exploits brought him to the attention of Student and Bräuer, who tapped him for the assault on Dover. In long conversations, the two had come to form a deep appreciation for Kroh’s leadership qualities and understanding of airborne warfare. The Führer had personally approved his nomination as reserve commander of Operation Rösselsprung, and, in the event, its second-in-command.

As Bräuer was assaulting the Citadel after midnight, Kroh and four companies of assault pioneers had landed in the fields around Dover Castle. They had found the great medieval fortress almost totally unprepared for a landward attack, and had quickly stormed across its intact causeways and into the inner bailey. About two hundred British soldiers had been in the Castle that night, but they were mainly the support personnel housed there and a contingent of artillerymen. After a series of brief firefights, the garrison had surrendered, and Kroh surmounted the keep to launch the flare that would signal Bräuer that the first English castle had fallen to a Continental invader in over seven centuries.

“What the devil is this?” Kroh’s driver whispered, braking. A line of uniformed figures was marching across the road into the field beyond, carrying what looked like petrol canisters. “They’re children...”

“Don’t shoot.”

The driver eased the lorry forward for a better look. Sure enough, it was dozens of children -- some surely as young as eight or nine -- crossing the road heedless of the approaches motor vehicles. “Stop,” Kroh ordered. They waited until the strange troop had cleared the roadway before proceeding again, and up onto the A2. “Keep going straight for some time now.” Kroh held a small flashlight over his folded map. They were passing around the outskirts of Dover now, and had soon made it without incident to the roundabout that marked the start of A2’s long, straight run past the eastern side of Lydden.

They had not gone far when a long line of lorries came into sight coming toward them. Kroh removed his rounded parachutist-style helmet and instructed the driver to do the same. Paying the northbound vehicles no mind, the long motor convoy passed along at walking pace, and Kroh soon saw why. Following the thirty or more covered lorries were several companies of armed men marching in good order. When they had passed the last of them, Kroh ordered his force off the road, and dismounted to reconnoiter Lydden with his binoculars. From this vantage, he couldn’t see any sign of the enemy brigade said to be headquartered there, but there wasn’t time for a more extensive survey. He returned to the lorry and got on the radio to Bräuer.

“Oberstleutnant, this is Kroh.”

“Go ahead, Kroh.”

“Oberstleutnant, be advised that there are approximately 700 enemy soldiers coming southbound on the A2, about a third of them motorized. We can detect no sign of brigade strength in Lydden from the road.”

“Proceed toward those guns, and reconnoiter more fully on the way back.”

“Yes, Oberstleutnant!” Kroh hung up the radiotelephone and ordered his convoy back onto the road. They followed the A2 for about five more kilometers, passing a pair of military ambulances going south, until Kroh finally found the junction with the Canterbury Road. According to the map, this was where they should leave the road and drive overland to the west until they encountered the railroad coming up from the Elham Valley.

To their left was a stand of trees with a long wrought-iron fence beyond. The convoy pulled off to the shoulder of the road again, and Kroh dismounted for a conference with his platoon leaders. Leutnants Becker, Koch and Frischer followed him to the fence and crouched over the map. “So, the fence isn’t on the map, but hopefully the bolt cutters can handle it. Then we’ll drive straight across Broome Park and hit the tracks right about

there after almost exactly 2 kilometers. Keep your men out of sight, and there is to be absolutely no shooting except if we are fired upon.” While Kroh took questions from his lieutenants, a pair of assault pioneers emerged from one of the lorries with a set of heavy bolt cutters. They fitted its stubby jaws over one of the fence’s horizontal bars, and clamped down. At first, nothing happened. Then, squeezing and straining, they forced the blades deeper into the bar, which creaked loudly. There was a sudden, grinding moan, and the iron gave way. The fence was built of sturdy latticework, and it was almost fifteen noisy minutes before the bolt cutters had bitten through enough bars to topple a section wide enough to drive through. But topple it did, with a final clanking crash, and Kroh’s seven lorries roared through the breach, and onto a wide grassy lawn.

They rolled down a gentle slope, onto the immaculately manicured grass of a putting green, which the lorries’ military tires mauled cruelly. Leaving great muddy tracks, they jounced along the rolling landscape of the Broome Park Golf Course, which seemed totally deserted; across sand traps, down the fairways and through a gap in the trees. A high hedge marked the western boundary of the course, and the Germans bulled through it and into an open field. “We’ll cross three small roads, now,” Kroh told the driver, and in moments, they did. After crossing the third, a rail embankment came into view and Kroh faintly made out the tracks.

The company turned right -- north -- and followed the tracks along the edge of Barham, namesake of the feared British battleship. In the blacked-out town, there were no men manning the anti-aircraft guns that stared blindly up at the clouds, but, for the first time, Kroh saw small numbers of civilians in the streets. Several buildings in the town center appeared bombed-out, with exposed roof frames and soot-blackened walls. In the distance, a policeman was talking to a woman outside a two-story pub. Kroh quickly turned away. The tracks passed across a narrow overpass now, and the lorries actually drove along the rail-bed, the deep boom of artillery growing louder ahead of them.

It was nearly dark now, and the German drivers peered ahead with difficulty as the convoy bumped ahead uncomfortably between the rails. Soon, distinct flashes of orange could be seen lighting the ceiling of clouds in the northern sky, and seconds later, the deep rustle of heavy shells passed high above. Another kilometer, and huge bright fireballs could be seen almost dead ahead whenever the guns fired. Kroh radioed Bräuer. “Enemy artillery spotted ahead. Will reconnoiter positions and enemy numbers, then attack.”

The Oberstleutnant barked a harsh, distant laugh through the ether. “Shock and firepower, Kroh. Report again when you have assaulted the guns.”

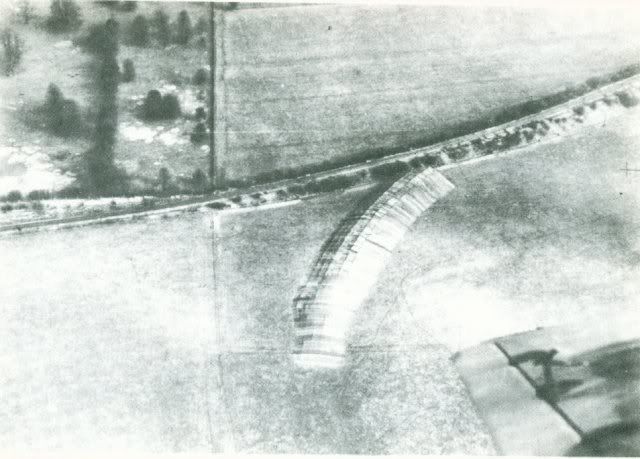

“Clear. Kroh ending.” He hung up, and ordered his driver off the rail bed, and into a wide, rolling field to the left, where they continued forward to get a safer look ahead. About 300 meters away were two long, lighted tunnels that seemed to emerge from underground, and opened to rail spurs on opposite sides of the main tracks. On each spur sat a huge artillery piece on a railroad chassis, with what looked like a support car close behind. The first gun was about 100 meters ahead of the second, Kroh judged, and through his binoculars, he could see the silhouettes of dozens of crewmen serving each gun wagon, which appeared to be moored in place by numerous cables.

Concealed firing spur north of Barham, German reconnaissance photo.

A giant bloom of white flame appeared in Kroh’s peripheral vision. To his left, he could see that there was a third gun, maybe 700 meters further to the north. He ordered the rest of the convoy to a halt, and only his own lorry forward. Just across the tracks was a large, poorly blacked-out country house with several staff cars in the drive. Reaching the far end of the field, Kroh could see that the third gun was firing from a curved siding with steep embankments on both sides, and dwarfed even the first two.

British 18 inch gun, Kent. Autumn, 1936.

A large crew was responsible for the guns’ operation and firing in time of emergency .

Kroh ordered the lorry around and back toward the others. His platoon leaders were waiting. “Becker, hit the first gun. Koch: the second, to the left. Frischer, you’ll go with me to hit the bigger one. We bring the explosives up by hand. I want each of you to leave one trupp as cover. Your other two squads will be for assaulting the crews at close range, and then disabling the guns

quickly. Thermite, naturally, and HE on the tracks and machinery. Clear?”

The lieutenants nodded in the darkness.

“Send a runner to me when you are set for the assault. Do not begin the assault until my signal, unless attacked. When we’re all ready, one green flare, then the assault begins. Good luck.”

The platoon leaders whispered in the darkness to the sergeants of their truppen. Then, the 67 assault pioneers were off at a running crouch. Fanning out toward the objectives, they fell prone at the lip of the short, shrubby slope overlooking the near side of the railroad. Just 25 meters away, the gun crews worked, illuminated every few minutes by the brilliant flashes that followed the great shells out the barrels.

Kroh and Frischer’s platoon pressed themselves flat along the embankment overlooking the largest gun. Every time it fired, the ground all around the siding threw up dust like a carpet stiffly beaten. As the loading gangs were ramming the next shell into the breech, the Germans selected their targets. It looked like three or four men were standing guard with rifles slung, but they formed no semblance of a perimeter, and the MGs would cut them down before they even knew they were under attack.

Fools. Kroh plugged his ears and opened his mouth. He heard the shot less than he felt it -- a painful weight forcing the air from his lungs. His eyes had been squeezed shut and turned away from the fireball, but his night vision still swam.

A hunched shape dived up behind him and squeezed his shoulder. “3. Zug positioned!” The second runner slid next to Kroh just moments later. “2. Zug positioned.”

Kroh turned toward where he knew Frischer was. “Everything in order?”

A hoarse whisper: “All in order. On you.”

Kroh slipped the flare pistol from its belt holster and loaded a green rocket. “We wait until the moment of the next shot.”

Laboriously, the next huge 1,510 kg shell was loaded, the charges rammed and the breech sealed. Kroh’s finger mounted pressure on the trigger. In the distance, he could hear the officers shouting final commands as the crew prepared to fire. A little more pressure.

A searing white fireball burst from the barrel, and before the flare was a dozen meters in the air, all four guards had fallen. Kroh and the assault squads sprinted down the slope firing, as those behind them hurled storm grenades. The three MG34s scoured the gun carriage, cutting down the artillerists at their posts.

Kroh reached the ladder at the back of the carriage, and found three British soldiers lying there, faces pale green under the flare’s cold light, uniforms black with blood, eyes wide and staring. Slinging his submachine gun, he scrambled up, taking stock of the loading area. Two assault pioneers were already there, picking through the heaped dead to reach the gun’s breech.

Renewed crackling behind him caused Kroh to whirl, and he saw a handful of surviving crewmen trying to jump down from the ammunition wagon a railcar-length behind the gun carriage. They stumbled and fell in the submachine gun fire. More assault pioneers climbed onto the car and emptied magazines into the open doorway.

In seconds, the shooting was over, replaced by the deadly hiss of white-hot thermite melting through the 18 inch bore of the gun. Even at the rear of the carriage, the radiant heat was painful to the skin. Kroh called down directions to his men as they set charges to destroy the ammunition car and the abandoned diesel locomotive prime mover still further behind. On the other side of the gun carriage, assault pioneers were planting high explosives along the tracks.

One of the sergeants called Kroh over to inspect the gun’s breech. It had been sealed shut by the ferocious heat of the thermite reaction, the lower part of the bore burned cleanly through, with a ragged hole still glowing cherry red. The molten steel had pooled on the floor of the loading platform, forming around the outlines of crewmen either dead or too badly injured to escape. The sergeant lit a slow-burning fuse on a bundle of explosives taped to the rammer and loading track. “All set, Major.”

Kroh climbed down and surveyed the area. Several dozen British soldiers lay dead all around the great artillery piece. Fuses were burning that would devastate what remained within five minutes. “1. Zug! On me!”

The last charges were set, and Frischer’s assault pioneers fell in behind Kroh at a run back toward the parked lorries. The other platoons were already mounting up -- Becker and Koch had had similar success disabling the two smaller guns. Every man was alive and accounted for. There were only a few minor injuries. A lone Englishman had been gagged and bound for interrogation back at the Citadel.

“Oberstleutnant, this is Kroh.” The major waited for a response over the radio. “Come in, this is Kroh. Do you receive?” There was no response. Kroh ordered the radioman to keep trying.

The motor column turned around and followed the railroad tracks south toward Dover. Just outside Barham, a white light burst into the sky behind them. Kroh hung his head out the window and looked back. Two points of white fire were blooming upward, twisting into towering pillars of roiling smoke and flame. Kroh glimpsed a rustle through the field grass, and the column was rocked by a thunderous boom lasting several seconds.

The tracks curved, and a stand of trees obscured what were now leaping flames tens of meters tall. When they came back into view, Kroh could see the area wracked by several smaller explosions that threw burning chunks of debris high into the air.

Kroh’s eyelids were closed in blinking, but he sensed a sun-bright flicker in the direction of the ruined guns. By the time his eyes opened, a third ball of fire, behind the first two, was already twice as tall and surging upward. Even at this great distance, he felt the heat. The top of the fiery cloud was turning end over end and flattening out high above Kent. This time, the shockwave violently jarred the lorries’ whole frames, but the assault pioneers registered little sound.

As the lighter fragments of the 18 inch ammunition car still rained down over the countryside, the German column passed Barham and turned left onto a side road that ran along the edge of Broome Park Golf Course, hoping rejoin the A2.

When the south-running highway came into view, though, the running lights of a long British column were streaming toward Dover. Kroh ordered his lorries into a ditch with their motors off and lights out. The assault pioneers waited in darkness, watchful for any sign that they had been seen by the enemy, until the rearguard finally passed out of sight.

The Germans turned onto the A2, avoiding a string of staff cars racing northbound in the direction of the still-burning railway guns. The column of British lorries was about half a kilometer ahead, and turning onto the London road that would take it into Dover’s city center. Kroh ordered his drivers up to speed, and they followed A2’s curve east of a darkened Lydden and onto the Dover approaches until the Castle came into view, faintly lit by a string of fires burning below.

“Any luck on the radio?”

“No, Herr Major.”

Kroh ordered the headlights on for the final run toward the German pickets, and fired a string of flares to announce himself. Assault pioneers hung from the sides of the lead lorries holding flashlights to swastika flags.

Finally, as they neared the castle’s outer walls, a machine gun burst lanced overhead from an unseen position on the slopes below the Castle. Kroh’s column rolled to a stop as a Feldwebel emerged from cover at the roadside and ran to the left window of the lead lorry. “Major Kroh?”

“Yes. Kompanie 8 is back intact. All enemy guns disabled.”

“Get out, if you please, Major. I need to speak with you.”

That was a queer thing to say. “Say whatever it is here, Lang.”

“Major Heilmann’s orders, Major.”

“Heilmann’s?” Kroh jumped out of the lorry and pulled Feldwebel Lang to the roadside. “What’s happened?”

“Direct hit on headquarters up at the Citadel. The Oberstleutnant is badly wounded. Major Heilmann had command until your return, but you are now acting commander of Sturmabteilung Bräuer.”

“Wait. When?”

“The better part of an hour ago. He’s in surgery at the Drop Redoubt.”

Kroh turned. “Frischer!”

The lieutenant jumped out of the lorry and ran over.

“Frischer, Bräuer is wounded. Take the company back up to the Castle, send them out to the lines as needed. Once they are in place, you may say that the Oberstleutnant is wounded, but make no mention of his actual condition. I’m going to take a car and see him right away.”

Ten minutes later, Kroh was shown into a floodlit operating theater in one of the Drop Redoubt’s kitchens.

Several medics with bloody gloves were clustered around Bräuer’s compact frame as he lay on a mess table. He was stripped naked, his chest bound tightly with gauze and dressings -- a medicine drip in one arm and saline solution going into the other. His pale legs were dotted with dozens of pea-sized shrapnel wounds that didn’t seem to merit medical attention in light of the chest injury.

“Sani, why is he tied down to the table?”

The peacetime obstetrician pulled up his surgical mask and picked a crumpled object off a nearby tray. “Six centimeters. This went into him. Steel. He refused morphine at first. By the time he made it to surgery, he had lost so much blood that any morphine would have killed him. We had to operate with no anesthetic.”

Kroh walked toward the table. Bräuer’s face was ashen, spattered with mud and blood -- his hair was singed and matted. He was either sleeping or unconscious. “Will he make it, Sani?”

“It will be close, Major. If his body can restore blood volume, he should wake up. If not --”

“There isn’t a tougher bastard in the Wehrmacht, Sani. He’ll wake up.” Kroh stormed out of the room, shaken deeply.

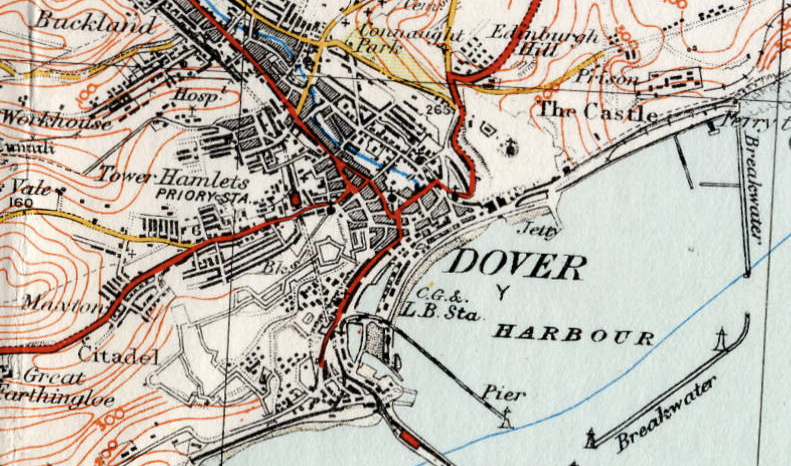

The British were visibly stirring on the north end of the city by 2000. An Oberleutnant drove Kroh across the top of the Heights to begin a survey the German perimeter. Hauptmann Wulpp’s Kompanie 6 held a line of positions running from the cliff’s edge across the A20 and up to Dover Citadel. Hauptmann Barenthin and Kompanie 1 occupied the Citadel itself and some of the barracks and administrative buildings just eastward along the Heights. Major Heilmann had three companies strung out from the north-facing works just east of the Citadel all the way to the Drop Redoubt. Hauptmann Pietzonka was just below the Drop Redoubt in the city itself, with his three platoons in and around Dover Priory railway station. The inner perimeter along the docks was manned by Kompanie 7 and the Kriegsmarine demolitionists, whose line joined that of Kompanie 9 at Dover Castle. This was reinforced by Kompanie 10 and the newly-returned 8, whose lines wrapped around the castle and down to the water. All told, there were 119 reported dead, several dozen critically injured and scores of walking wounded.

Dover’s Western Heights, looking west.

Dover Citadel, German reconnaissance photo.

Kroh ordered the distribution of more stimulants. It seemed that the British would not wait for dawn to launch their attack. Taking up a new command post with Heilmann at the Drop Redoubt, Kroh watched through his night glasses as rows of kettle helmets began streaming silently southward through streets and alleys, working their way down toward the docks.

“They’re going to be probing,” Kroh radioed Hauptmann Adler atop the keep. “Hold your fire until they’ve committed totally. We should avoid giving away our position.”

At 2047, Pietzonka’s men made contact with platoon-sized enemy forces occupying a row of flats across from German positions. Fire was traded inconclusively, as several British foot companies rapidly swept down toward the docks. Kroh sent flares up for illumination, and the men at the Drop Redoubt finally opened fire, machine guns raking the streets far below. After a few minutes, it became clear that the advance had been halted, but the assault pioneers also saw that the enemy was not driven back by the enfilade. Rather, they had taken what cover they could, turning fences and houses into fortified positions and daring the invaders to dislodge them.

The British were just three blocks away from the docks now. Kapitänleutnant Urich’s men heard the faint clatter of moving infantry ahead, but as his sharpshooters and machine gunners strained their eyes into the deep shadows of gutters and alleyways, they saw nothing.

2100. Then 2200. Still nothing. Kroh considered standing some of the men down to sleep, but the signs from the city were still too threatening. Observers atop the keep of Dover Castle could see British forces gradually coming down through the city in battalion strength. If large forces got too close to the docks, Urich would be in danger of being overrun, regardless of German strength elsewhere.

Just before midnight, contact was reengaged down at Dover Priory, as Pietzonka’s pickets engaged small enemy units trying to work around him and up toward the Heights. Exposed by a star flare, they took heavy casualties and withdrew.

Adler called again from the Castle. “My observers see what appears to be an enemy battalion gathering at the Town Hall. It would be the logical place to set up a forward headquarters, yes? I suggest we hit them with the mortars.”

Minutes later, all ten of Sturmabteilung Bräuer’s mortars opened fire. The accuracy of their plunging fire left much to be desired, however, and by the time the haphazard barrage actually managed to hit the old town hall building, it had been safely evacuated. Kroh called the mortars to a halt, and deputized Hauptmann Adler’s observers to create ranging tables for the city and its approaches.

Dover, mid-1930s.

The first hours of December second passed in silent darkness, the German lines on full alert, as the observers relayed news of two whole battalions gradually slipping closer. Eventually, some British units strayed too far into the open and were cut up by the machine guns around the Drop Redoubt. Others were felled by Kroh’s sharpshooters as they tried to reconnoiter ahead of the main force. On the main, though, Dover was silent, and the scattered fires that were still burning in the city from the heavy artillery showed no signs of spreading.

Now and then, Kroh and Heilmann slipped into the operating theater below their headquarters to check on Bräuer, but the Oberstleutnant did not wake. Kroh relayed news of the commander’s condition to Student in France, but the latter could not offer the comfort of any firm news of coming relief.

By the dead hours of the night, Adler could report no definitive signs of attack, so Kroh radioed the Castle, the Citadel and the docks to order their lines down to half watches and rotate the forward pickets on the hour. The British seemed to be planning a dawn attack after all, and Kroh wanted every man to at least have a couple hours‘ sleep before battle was rejoined.

Kroh was just completing his telephone call to Wulpp when an Unteroffizier entered the headquarters and reported the start of an attack on Dover Priory. Kroh raced up to his observation post atop the Drop Redoubt and ordered a general alert.

Several white flares were burning above the city, and Kroh could see flashes of gunfire around the railway station. The Heights were too shallow along their northern slopes to afford him a truly commanding view, but Pietzonka’s men kept him informed by telephone: enemy soldiers were streaming across a small park that abutted the priory school.

Pietzonka held them back with grenades and machine guns, but the attack quickly redirected -- this time, the British stormed a narrow gap separating the row of flats from the railway station’s outer fence. Kompanie 5 had two MG34s on the station’s roof which did yeoman’s service in preventing all but a handful of Tommies from crossing onto the tracks. Those that did, however, charged the platform led by a captain, and managed to kill several assault pioneers at close range before being cut down themselves by a reserve squad rushing out of the station house.

The British assault let up, but Adler’s observers were now reporting probing movements closer to the Castle, and pickets just outside the Citadel reported suspicious movements in the darkness below them.

Every half hour or so, firing would break out somewhere along the German lines, but still the main British force remained in reserve.

Several companies moved south at once around 0530, but despite harassing machine gun volleys and even a second abortive mortar barrage, stayed firmly put in buildings just two blocks north of the docks. Urich’s men -- on roofs, at attic windows, in wharf scaffolding and crouched in foxholes dug along the boardwalk -- waited for the blow to fall.

As the sky began to lighten, Kroh dispatched Ludebrecht’s Kompanie 3 down from the Heights to reinforce the docks. The furtive movements of the night gave way to a fitful stillness among the British forces. Kroh knew that somewhere in the northern part of the city, his opposite number was almost surely counting down the minutes to 0744: dawn.

Kroh ordered another round of caffeine tablets. Insects began to buzz on the frost-covered grass crowning the Heights. With the sun’s warmth would come the carrion. During the night, assault pioneers had taken in most of their own dead, wrapping them in canvas and laying them out in cool, dark places. Most of the British dead lay where they fell, though. The Western Heights alone were strewn with more than fifty left in the open.

It was dawn. The sky was thickly overcast, but somewhere behind, the sun was rising over the North Sea. The Germans tensed, waiting for the whistles or bugles that would signal an attack.

Fifteen minutes passed, but no attack came.

“Major Kroh, the Oberstleutnant is asking for you.”

“Sani?” Kroh turned to see Sanitäts-Leutnant Sanger coming up the staircase from the mess hall. Following Sanger down and into the operating theater, he found Bräuer awake, but semi-delirious and in great pain.

“Kroh, for God’s sake, get over here.”

“I’m here, Oberstleutnant.”

“Tell them -- tell them.” His voice cracked, and Bräuer gritted his teeth. “Is it dawn?”

“Yes, Oberstleutnant.”

“Expect a counterattack. Get another company down to the docks, and hold onto the.” He closed his eyes. “Get another company down, down to the docks, and hold onto the railway station.”

“It is done, Oberstleutnant. Everything is under control.”

“Give the men their caffeine, Kroh. They need caffeine to stay awake, Kroh.”

“I did, Oberstleutnant. You trained us all very well.”

“Don’t let them, they, I,” Bräuer swore. “Get me a blanket!”

Kroh cast about the operating theater, unfolding a small blanket that he found on a counter.

“Don’t make the Major do it, numbskull!”

“It’s alright, Oberstleut --”

“I asked Sanger to get me a blanket. Or does he only follow orders given wrapped around a pistol?”

Kroh sheepishly handed the blanket to the doctor, who spread it over Bräuer’s body and backed away.

“Get some rest, please, Oberstleutnant. May I return to the command post?”

“Go.”

The morning was wearing on, but still the British did not attack.

Finally, a group of previously-unseen light field guns barked near the crest of the hill opposite the Heights to the north. For fifteen minutes, high explosive rounds burst among the wharves, smashing a crane and setting a warehouse on fire, but achieving little tangible result other than giving the Germans warning.

When the barrage came to an end, Urich’s gunners were squinting ahead down their iron sights, waiting for the shrill whistles that sounded as if on cue as the smoke from the last shell impact cleared.

With a swelling roar, four hundred men of the 7th Hampshires rose from their sheltered positions and charged for the docks. The two MG34s at the attic windows of the Young & Jarrow warehouse clattered to life, cutting down enemy soldiers as they came down King street. Others appeared in second-floor windows of restaurants and shops along the dockside, firing down on dug-in Germans with their long rifles -- and even, in one case, setting up a Lewis machine gun, which quickly raked a turned-over Hillman that a pair of sharpshooters was sheltering behind.

An MG crew along the docks saw the plight of the two wounded riflemen huddled behind the fast-disintegrating automobile, and ran their weapon into place to get an angle on the British gun. The keen-eyed Hampshire spotted them at once, though, and sent so many rounds into the tire pile they were setting up on that it caught fire.

Further to the west, on the opposite side of King street, a British platoon had gotten into grenade-throwing range with assault pioneers dug in across the A20. Men in full view of each other tossed fragmentation bombs back and forth at one another with all the cheek and rudeness of spitballs. It was only when a “cooked-off” grenade blew an Oberjäger’s arm off before he could throw it out of his foxhole, that the Germans got mad in deadly earnest, and threw phosphorus across the highway.

The centerpiece of the dock defenses was a sandbagged antiaircraft installation built around a British 40 mm Bofors gun and reinforced with three MG34s with a good line of sight to the juncture of Queen and York streets. This small square was now a shambles of overturned fish carts and market stalls, which the Bofors violently tore apart as hard-pressed Hampshires sheltered there before the final charge.

Urich’s firepower was vastly more formidable than the British seemed to have expected, but officers urged men on and men urged each other on -- and soon, the survivors of four companies were hurling themselves across the last open meters in front of the German lines.

Exposed to the full ferocity of the pioneers’ submachine guns at last, more than a third of them fell. Potato masher grenades tumbling end-over-end landed around and among them, and men lent hands to pull up wounded comrades that had fallen in the killing zone.

A squad with a flamethrower appeared on the roof of the Young & Jarrow warehouse when the Hampshires were almost to the front doors, squirting liquid fire onto the poor souls below until a British sharpshooter put a bullet between the nozzleman’s eyes.

But although the enemy was scythed down by the score, some of them inevitably got through.

One foxhole was overrun only after the five survivors of a platoon leapt in and bayonetted the occupants to death. Another British captain, his jaw shot off, managed to lead a handful of riflemen straight through a weak point in Urich’s lines and onto one of the piers. There, they took potshots at the German squads racing back and forth to plug the gaps.

A short distance to the east, some thirty men advanced under the cover of the second-floor Lewis gun and stormed a German-held accounting office between two warehouses; the MG crew firing from its loft fled onto the roof.

The Young & Jarrow building saw close fighting, too. A British section taking advantage of the lull in the flammenwerfer’s fiery ministrations raced up to the façade and smashed the windows, climbing through the frames and into a dimly-lit firefight with four Germans that quickly devolved to knives, marlinspikes and desperate punches.

Hand-to-hand fighting reached all the way to Urich’s customs house headquarters, which the towering demolitionist defended by sticking his Luger out the window and picking off Tommies whenever he got a clean shot amidst the chaos of grappling bodies.

After fifteen minutes, though, the attack began to run out of steam. Shattered companies of Hampshires pulled back across the boardwalk, dragging what wounded they could. They had grasped the assault pioneers by the collar and made them bleed, but lacked the strength to do any more. They had died in heaps under the Germans’ massed automatic weapons, but with the exception of the single foxhole, had failed to overrun any position outright. Failing a general breakthrough, it was only a matter of time for the regrouping assault pioneers to harry the survivors off the docks and back into the city.

Watching the withdrawal from on high, Kroh radioed Ludebrecht to lead his company in after them.

The counterattack of Kompanie 3 caught the Hampshires on the run, and the British couldn’t find purchase on any of a succession of blocks to slow them. Ludebrecht found dozens of injured men lying outside a small whitewashed public house hung with a black-letter sign: The Cause is Altered. The British battalion commander had made this his headquarters, but fled out the back door as his pursuers broke down the front -- retiring to a church several blocks away that had a defensible belfry.

As his sergeants warned the men away from tapping the unattended casks, Ludebrecht sent a runner back to Urich, who radioed Kroh: what to do with the prisoners?

Kroh saw plainly that his outnumbered force could not guard and care for a large number of injured captives. He considered descending to the surgery to ask Bräuer’s advice, but thought the better of it. The Oberstleutnant was no monster, but he made no pretensions of chivalry, either. He had, after all, pistol-whipped the commandant of Eben-Emael, it was said -- and rumor had him failing to notice the upraised hands of a French flying officer accused of murdering German pilots.

“Tell Ludebrecht to pull back to the previous lines, Kapitänleutnant. John Bull learned his lesson this morning.”

“Yes, Major. At once.”

The Dover waterfront was a smoldering wreck. The flamethrower had splashed Flammöl 19 -- gasoline mixed with tar -- onto a row of storefronts which now burned cheerily in the no-man’s land between the two forces. Warehouses, offices and cafés for five hundred meters had been riddled with bullets, their windows shot out. Blood ran in rivulets off the A20 into its flood ditches; on the older streets, it pooled in wagon ruts carved by farmers coming to provision Nelson’s fleet.

While the Hampshires were attacking the docks, Kroh had ordered his mortars to hit the hill crest where the British field guns had unlimbered on the other side of the valley. This time they had better spotting, and Adler’s observers reported that the enemy artillery had been driven out of sight.

Despite successfully repelling the the British onslaught, however, Kroh was uneasy. The sea was still unacceptably high, and as long as it remained so, Sturmabteilung Bräuer was on its own. The 7th Hampshires, his interrogators reported, were but a third of the brigade thought to be now headquartered at the head of the Stour valley, near the northern outskirts of the city. The other two battalions, both Dorsets, could be seen making their way down to reinforce their brethren, and would surely attack again soon.

In the meantime, the Germans counted their own dead and tended to their own wounded. Fresh ammunition was driven down from the Castle to supply the empty magazines along the docks. There was so much work to be done repairing defenses, carrying supplies and -- above all -- digging deeper, that even now, the exhausted assault pioneers could be allowed no rest.

Biting sleet came down in sheets again, drawing cold, gauzy clouds around the embattled city. From the slopes below the Citadel to the highest parapet of the Dover Castle’s keep, the Germans strained through foggy binoculars to catch some hint of movement in gloom.

Major Kroh came down to the operating theater to find Heilmann already there on one knee, listening stiffly to what could only be a faint, raspy sermon on “Shock and Firepower.”

“The men at the docks did well, Oberstleutnant.”

Bräuer, restrained as he was, could not turn his head to see his soggy lieutenant. “Kroh? Come where I can see you.”

“Yes, Major?”

“If I were that brigadier, I would send everything I had right back at the docks as soon as I could.”

“That makes sense.”

“Send another company to reinforce the docks... How many machine guns does Urich have down there?”

“Almost thirty.”

“He needs more.”

Kroh nodded. “I’ll send another down.”

Two sanitäter rustled in from another curtained section of the kitchen where they had been tending to a Leutnant with a shattered leg.

“Will that be all, Oberstleutnant?”

“Shoot these lunatics if they come near me.”