Chapter III: Part XIX

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XIX

September 26, 1936

Two crickets were chirping loudly from opposite ends of a narrow clearing. Tall grasses standing in an inch of water swayed almost imperceptibly in the night air. The cricket at the far end of the clearing fell silent. The near end of the clearing was bordered by a shrubby berm that looked down on the mirror-smooth course of the Lower Rhine. It was a warm night. The second cricket fell silent.

With hypnotic slowness, Fritz-Albert Geier edged his body up to the berm and pulled himself over its top. Half-covered by calluna, he slipped his binoculars to his eyes and surveyed the small red-brick building on the riverbank. He could plainly see that the structure was complete, but its two small windows were dark. Good. This was the brand-new Roost-Rhenen flooding station -- a crucial part of Holland’s shield against German aggression.

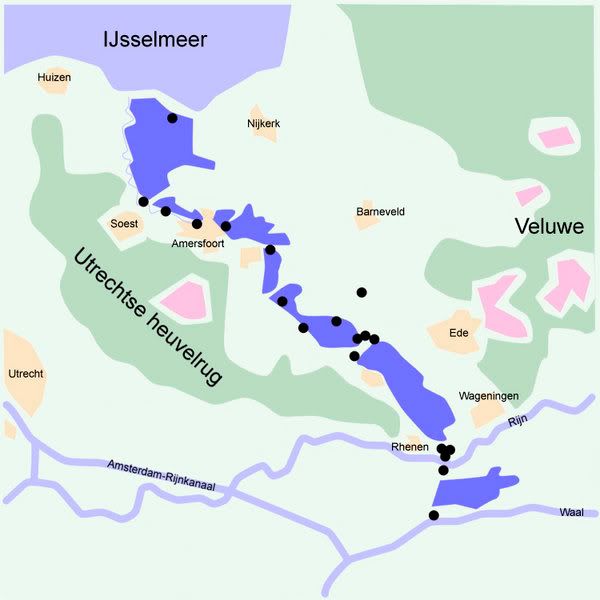

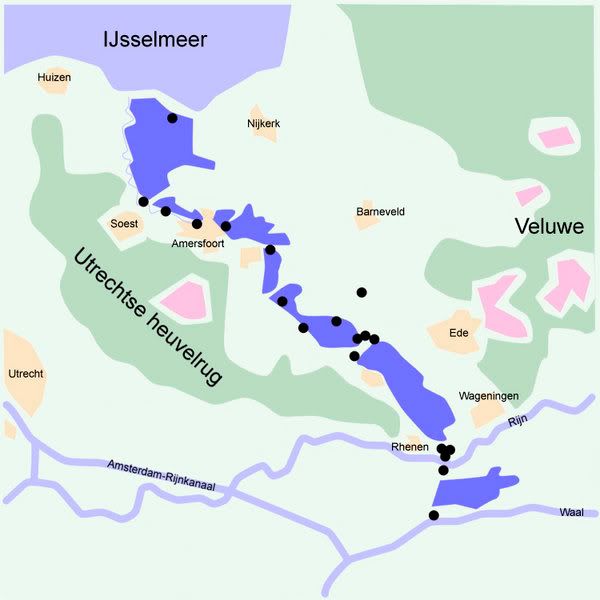

The area near the Roost-Rhenen flooding station, early 1936.

Since June, the Dutch had been frantically attempting to refortify the several defensive lines which they had dismantled in the twenties. Construction of steel-and-concrete fortifications was progressing as rapidly as the available labor force would allow, and the formidable Grebbe Line was now congealing as the most viable bulwark along the eastern edge of Holland proper. By the middle of September, enough ground had been dredged along the Grebbe Line that on orders from the Dutch high command, water could be pumped out of the IJsselmeer to flood a swath of low-lying ground running all the way south to the Rhine. This inundated ground, covered by water too deep for men and vehicles to cross effectively but too shallow for most boats to navigate, would form a taxing obstacle for von Bock’s 2. Armee as it barreled westward toward Amsterdam.

The Grebbe Line, with areas to be inundated in blue.

Yet the haste with which the Grebbe Line was being completed meant that until the completion of the pumping stations near Bunschoten at the north end of the line, the area could only actually be flooded from the south. For it was here that the unassuming brick building in Geier’s binoculars controlled the massive river-gates that could divert water from the Rhine near Rhenen into the country around the river IJssel. Because the elevation of the riverbank was somewhat raised, a concrete outlet had been built that would channel the water about a hundred meters northward into lower ground where it could flow freely, rapidly forming an impassible barrier.

HKK knew that disabling the flooding station at Rhenen would keep the ground dry and shave precious days off the timetable to subdue the entire country. Canaris and the Abwehr were still worried about the prospect of British intervention if the fighting took too long, and so resolved to cripple the Grebbe Line before the start of the invasion. Geier, fresh from the Mediterranean, had been sent to Utrecht to make contact with Markus van Driel’s cell. Worldly and highbrow, Geier had been alarmed by the Dutchman’s instability and rough appearance. Within two nights, some of van Driel’s men had gotten into a scuffle with a local night watchman. Geier had arrived on the scene to find van Driel egging on a huge henchmen to beat the watchman to death with a crowbar. Returning to the safe house after narrowly defusing the situation, Geier had taken the fascist leader in private and shown him his Menta pistol. He was the absolute commander of the operation, he told van Driel, and would go to all extremities to ensure that that operation was not compromised in any way. Geier had found him pronouncedly more docile in the days since.

On Wednesday, the twenty-third of September, Geier had received the coded confirmation. Operation Gewürz, the invasion on the Netherlands, would commence two hours before dawn on the twenty-sixth. With two other Germans who would arrive in Utrecht the next morning, and the men of van Driel’s cell, he was to infiltrate the flooding station at Rhenen -- in the very heart of the Grebbe Line. The Abwehr knew that the station itself was very poorly defended. German officers in civilian clothes had been touring the area all summer in the face of lax security, and it seemed clear that the building would be occupied by no more than the five men that lived there and ran it. The hard part, Geier was told, would be slipping through the lines of outposts all around the flooding station.

And now, they were through it. Geier slipped his binoculars back into their case and rolled himself over the top of the berm and into a ditch on the other side. He scurried down its length to a leafy tree that would obscure him from the sight of anyone in the flooding station. There, he stood and brushed off his uniform -- that of a Majoor of the Royal Netherlands Army and stepped onto the dirt lane that led to the building. He checked his watch. Two thirty exactly. One by one, the other four men under his command stepped out of their shadowed cover and onto the road.

They were to enter the flooding station by deceit if at all possible. Too appearances, it was a Dutch major, lieutenant and three corporals that walked up the darkened road to the Roost-Rhenen station to deliver urgent news.

Geier rapped firmly on the door five times. Silence. Five more knocks. He could hear motion within. At last a narrow slit set into the door at eye level opened, revealing a long nose and a pair of sleepy eyes.

“Why wasn’t someone awake keeping watch?” Geier blustered in Dutch.

“I --”

“Did you receive the telephone call from the section headquarters?”

“I -- no. No, Majoor. However, we did not receive any orders about watch from the building itself -- we merely --”

“Are you going to keep us waiting out here in the cold at this hour?”

Geier heard the door unlock with two different deadbolts. The startled sergeant opened the door and turned on a light. Geier, van Driel, his compatriot Eggers, and the two other Germans Soll and Ascher, filed into the room. Although fairly small, the space still covered most of the building’s footprint. Against the far wall, the sergeant’s four companions were scrambling out of their cots to attention.

“We are here for a very serious reason,” Geier said. “It has been reported to command that it is possible that a German agent may have infiltrated this structure some time in the last twenty-four hours.”

“That is impossible,” protested the sergeant, “for surely if --”

“Quiet! You were all sleeping the night away, and I don’t expect that you would know the difference if a whole troop of Germans just pranced right into this building under your noses. Do not presume to tell me what is impossible.” Geier paused, marveling at his own audacity, and hoping that none of the others would somehow slip. “We must see the controls for the river-gates, to ensure that they are all functional in the event of an attack.”

“In the event of an attack, sir? We do not have standing orders to flood even in the event of an attack. That would have to come from higher headquarters.”

That was a relief. Geier made mental note to cut the telephone lines into the building. The Abwehr knew that the Dutch knew that hundreds of thousands of Germans were massing close to the border, and accordingly feared that standing flood orders might have been issued. Still, he glared at the Dutch sergeant and ordered him to take them to the control room. They descended a deep flight of stairs against the left wall of the room, and found themselves at a thick steel door which the sergeant unlocked.

They were in a small chamber -- illuminated by a single bare lightbulb, and slightly damp. Around the walls and in the center of the room were large metal boxes vaguely resembling upright pianos. Each one had an assortment of gauges and valve wheels across its surface.

“Are these the hydraulics?”

“Yes, Majoor. Each one of these controls one of the river gates. All six gates can be opened in less than five minutes.”

Geier inspected each one carefully. “Are there any other control points?”

“No, Majoor. These river-gates may only be opened from this room.”

“And they do not look like anyone has been tampering?”

“No, Majoor.”

“Good.” The six of them paced back up the stairs to find three of the sergeant’s companions sitting around their mess table, drinking tea and eating slices of bread.

“Majoor.” It was van Driel, in the process of lighting a cigarette. “Then are we to take it that everything is normal? There were clearly no signs of sabotage.”

“Yes.” Geier turned to the sergeant. “See to it that in the future at least two of your men are awake at all times, with the other three free to rest or sleep.”

“Without fail, Majoor.” The sergeant saluted.

Geier felt a sudden jolt of adrenaline. The sergeant. The three men at the table. Two plus three is five. One plus three is four. “Wait!”

“What?”

Geier raced across the room, scanning every corner. The bathroom was empty. There was no one left in the control room. Someone was missing. “Someone’s missing!”

In a fluid blur, Soll raced across the room and threw open the door. He bolted out into the night, followed closely by Ascher. Geier heard a muffled yell, but couldn’t follow them out to investigate.

“None of you move.” He wheeled on the remaining four Dutchmen with his Menta. He was into this at full depth now. “Slowly get up, with your hands in the air, and each one of you line up against the wall. One sound and you’ll all be shot.”

Eggers had drawn his concealed pistol as well. As the Dutch soldiers backed numbly against the wall, van Driel advanced on them hungrily with a long length rope. He tied each man’s hands behind his back and then tied them all to a large stovepipe against one wall.

“Get the explosives, now, both of you. I’ll watch the prisoners.”

Within ten minutes, the two Dutch fascists had returned with the explosives they had hidden nearby. Just as they descended to the control room, Soll and Ascher stumbled back into the building, badly winded. Soll was wiping his ankle-knife with a handkerchief.

Geier soon got out of them that Soll had sprinted after the fleeing private on foot. “When he was getting ahead I stole a bicycle even. I pedaled after him as fast as I could, but he went off the road into a sunken field, and I had to start back after him on foot. He disappeared twice, but at last I overtook him and pinned him down long enough for Ascher to arrive. He’s all taken care of. I don’t think anyone heard.”

“Good.” Geier felt relief sweep over him at such nearly-averted catastrophe. “The others just took the explosives below.” While the two skilled Germans went below to set the charges, Geier ordered van Driel and Eggers back out into the night to complete the second phase of the operation.

In twenty minutes, they returned. In the fields around the Roost-Rhenen flooding station, they had placed landing markers for the gliders of the small detachment of assault pioneers who would wreck the river gates themselves and then protect Geier and his men as they exfiltrated to advancing German lines.

Geier ordered the fuses primed. They would wait until they had the protection of the glider men before blowing the charges. The night was wearing on. Three twenty. Geier posted van Driel and Eggers outside to watch for the approach of the gliders. Three thirty. Three forty.

“Here they come!”

A hoarse whisper from van Driel sent Geier racing outside. He trained his gaze where the Dutchman was pointing. In the distance, four dark shapes were flying silently over the field on the other side of the river. They were moving slowly, in a shallow glide over the outer works of the Grebbe Line. No searchlights lanced up to meet them, no gunfire broke the darkness. At last, they were so close that Geier could distinguish the heads of pilots in the cockpits. They soared over the flooding station no more than a dozen meters off the ground, silent as a flock of birds.

The four gliders landed some distance away in a darkened field. Geier didn’t see any soldiers pouring out yet. He wished that they would hurry.

The beam of a flashlight coming up the road toward the flooding station drew his attention. A kapitein of engineers was walking his bicycle slowly toward them.

“Follow me and say nothing,” Geier hissed, beginning a series of long, confident strides toward the Dutch officer.

The man stopped in his tracks when he saw the three men approaching.

“Hallo, what is your business out alone at this hour?”

“There were reports of sounds of shouts or an altercation near the flooding station some time earlier tonight. I was sent to investigate.”

“Actually we were sent to investigate. It just seems that one of the non-commissioned officers posted here injured himself slightly in the night. A doctor is seeing to him now.”

The Dutch officer leaned his body first left, then right, seemingly trying to look past Geier’s body at the door to the building. “May I just take a look inside to confirm that everything is in order, then, Majoor?”

“I do not think that that is permissible. With the increased security here at present, I would need to see a written order from your commanding officer.” Geier sensed that the man would buckle soon.

“Halt! Lock!” All four men snapped their heads to the right, where three men wearing strange helmets had emerged from the bushes and were pointing submachine guns at them.

Geier gulped. “Key.”

“Which one of you is Geier?”

“I am.”

“Are all these men actually German?”

“Only me, but --”

In a startling second of gunfire, they had shot the others dead. Geier whirled, pointing furiously at the bodies of Eggers and van Driel. “No! Those two were our Dutch friends!”

“I’m sorry.” The Feldwebel brashly raced past Geier and opened the door to the flooding station. A dozen more assault pioneers had appeared, most of them pouring into the building. Geier simply stood there bewildered until a lieutenant approached him and saluted.

“This is Hauptmann Heilmann.”

A Luftwaffe captain with a haughty face paced up to Geier and saluted as well.

“What is the meaning of this, Hauptmann? Your men shot two men working for the Abwehr! And fired without being first fired upon!”

Geier saw the captain’s jaw clench grotesquely in the moonlight. “Accidents happen.” With that, the man spun on his heel and walked back into the flooding station.

Following him, Geier found Soll and Ascher coming up the stairs from the control room. “All the charges are set, Herr Geier. Two minutes to get out.”

Geier urgently passed the word to the assault pioneers, who began taking up positions around the building. The four Dutch prisoners were gagged and thrown out into the road in a heap.

At last, a lone assault pioneer charged up the stairs from the control room. “Thirty seconds! Get out, get out, get out!”

The men waited in the ditches around the building with bated breath. Then, a thunderous clanking rumble emanated from the bowels of the flooding station. Light smoke lazily wafted through the slit in the closed door.

Geier could hear alarms sounding in the distance. He made his way down to the concrete flooding outlet just upriver from the building. There, he saw a squad of assault pioneers working to wreck the river-gates. Several fierce and sparking points of light burned in the flooding outlet -- searing white-blue, and brighter even than welders’ arcs. He returned to find many of the assault pioneers back inside the flooding station.

He was pleased to find them moving the three bodies inside and covering them with sheets. The men looked terribly pale in the light, their faces glistening and tense.

Geier heard a faint thud, and the landscape outside was bathed in ghostly white light.

“Flares!” Hauptmann Heilmann shouted. “Get the men back inside as soon as they are done!”

The pops of gunshots immediately sounded in the fields outside the flooding station -- then barked orders from the officers.

Someone turned out the light inside the flooding station and the men within trained their weapons through the windows. The others -- there seemed to be about thirty in all -- were digging in around the building in what cover was available. Two of them came in through the door and set up a water-cooled machine gun in one of the windows. Geier saw that the hands of the gunner seemed to be twitching slightly. He hoped there would be no further friendly fire.

More pops in the fields. From his position, Geier couldn’t see what was going on there, but it didn’t sound terribly serious. Then frantic screams. “A whole lot of them! Help! Help!” Gales of automatic weapon fire continued for almost a full minute.

Then one of the soldiers near Geier at the window pointed toward the gully down the road where the van Driel had hidden the markers and explosives. “More of them!” The flares had burnt out, so the area was again too dark for Geier to see anything.

In a moment, the machine gun opened fire, strobing yellow light onto the gully. Bright tracers snaked from the barrel, dousing the low ground with bullets. In the flickering light of the muzzle flash, Geier could make out helmeted shapes crouching for cover.

Another flare blazed to life above them, revealing more helmeted shapes all around the flooding station.

The assault pioneers fired at them frenetically.

Heilmann paced back and forth at the center of the room, encouraging his men. “Keep firing, keep firing! Still more than an hour until morning.”

Chapter III: The Lion’s Den

Part XIX

September 26, 1936

Two crickets were chirping loudly from opposite ends of a narrow clearing. Tall grasses standing in an inch of water swayed almost imperceptibly in the night air. The cricket at the far end of the clearing fell silent. The near end of the clearing was bordered by a shrubby berm that looked down on the mirror-smooth course of the Lower Rhine. It was a warm night. The second cricket fell silent.

With hypnotic slowness, Fritz-Albert Geier edged his body up to the berm and pulled himself over its top. Half-covered by calluna, he slipped his binoculars to his eyes and surveyed the small red-brick building on the riverbank. He could plainly see that the structure was complete, but its two small windows were dark. Good. This was the brand-new Roost-Rhenen flooding station -- a crucial part of Holland’s shield against German aggression.

The area near the Roost-Rhenen flooding station, early 1936.

Since June, the Dutch had been frantically attempting to refortify the several defensive lines which they had dismantled in the twenties. Construction of steel-and-concrete fortifications was progressing as rapidly as the available labor force would allow, and the formidable Grebbe Line was now congealing as the most viable bulwark along the eastern edge of Holland proper. By the middle of September, enough ground had been dredged along the Grebbe Line that on orders from the Dutch high command, water could be pumped out of the IJsselmeer to flood a swath of low-lying ground running all the way south to the Rhine. This inundated ground, covered by water too deep for men and vehicles to cross effectively but too shallow for most boats to navigate, would form a taxing obstacle for von Bock’s 2. Armee as it barreled westward toward Amsterdam.

The Grebbe Line, with areas to be inundated in blue.

Yet the haste with which the Grebbe Line was being completed meant that until the completion of the pumping stations near Bunschoten at the north end of the line, the area could only actually be flooded from the south. For it was here that the unassuming brick building in Geier’s binoculars controlled the massive river-gates that could divert water from the Rhine near Rhenen into the country around the river IJssel. Because the elevation of the riverbank was somewhat raised, a concrete outlet had been built that would channel the water about a hundred meters northward into lower ground where it could flow freely, rapidly forming an impassible barrier.

HKK knew that disabling the flooding station at Rhenen would keep the ground dry and shave precious days off the timetable to subdue the entire country. Canaris and the Abwehr were still worried about the prospect of British intervention if the fighting took too long, and so resolved to cripple the Grebbe Line before the start of the invasion. Geier, fresh from the Mediterranean, had been sent to Utrecht to make contact with Markus van Driel’s cell. Worldly and highbrow, Geier had been alarmed by the Dutchman’s instability and rough appearance. Within two nights, some of van Driel’s men had gotten into a scuffle with a local night watchman. Geier had arrived on the scene to find van Driel egging on a huge henchmen to beat the watchman to death with a crowbar. Returning to the safe house after narrowly defusing the situation, Geier had taken the fascist leader in private and shown him his Menta pistol. He was the absolute commander of the operation, he told van Driel, and would go to all extremities to ensure that that operation was not compromised in any way. Geier had found him pronouncedly more docile in the days since.

On Wednesday, the twenty-third of September, Geier had received the coded confirmation. Operation Gewürz, the invasion on the Netherlands, would commence two hours before dawn on the twenty-sixth. With two other Germans who would arrive in Utrecht the next morning, and the men of van Driel’s cell, he was to infiltrate the flooding station at Rhenen -- in the very heart of the Grebbe Line. The Abwehr knew that the station itself was very poorly defended. German officers in civilian clothes had been touring the area all summer in the face of lax security, and it seemed clear that the building would be occupied by no more than the five men that lived there and ran it. The hard part, Geier was told, would be slipping through the lines of outposts all around the flooding station.

And now, they were through it. Geier slipped his binoculars back into their case and rolled himself over the top of the berm and into a ditch on the other side. He scurried down its length to a leafy tree that would obscure him from the sight of anyone in the flooding station. There, he stood and brushed off his uniform -- that of a Majoor of the Royal Netherlands Army and stepped onto the dirt lane that led to the building. He checked his watch. Two thirty exactly. One by one, the other four men under his command stepped out of their shadowed cover and onto the road.

They were to enter the flooding station by deceit if at all possible. Too appearances, it was a Dutch major, lieutenant and three corporals that walked up the darkened road to the Roost-Rhenen station to deliver urgent news.

Geier rapped firmly on the door five times. Silence. Five more knocks. He could hear motion within. At last a narrow slit set into the door at eye level opened, revealing a long nose and a pair of sleepy eyes.

“Why wasn’t someone awake keeping watch?” Geier blustered in Dutch.

“I --”

“Did you receive the telephone call from the section headquarters?”

“I -- no. No, Majoor. However, we did not receive any orders about watch from the building itself -- we merely --”

“Are you going to keep us waiting out here in the cold at this hour?”

Geier heard the door unlock with two different deadbolts. The startled sergeant opened the door and turned on a light. Geier, van Driel, his compatriot Eggers, and the two other Germans Soll and Ascher, filed into the room. Although fairly small, the space still covered most of the building’s footprint. Against the far wall, the sergeant’s four companions were scrambling out of their cots to attention.

“We are here for a very serious reason,” Geier said. “It has been reported to command that it is possible that a German agent may have infiltrated this structure some time in the last twenty-four hours.”

“That is impossible,” protested the sergeant, “for surely if --”

“Quiet! You were all sleeping the night away, and I don’t expect that you would know the difference if a whole troop of Germans just pranced right into this building under your noses. Do not presume to tell me what is impossible.” Geier paused, marveling at his own audacity, and hoping that none of the others would somehow slip. “We must see the controls for the river-gates, to ensure that they are all functional in the event of an attack.”

“In the event of an attack, sir? We do not have standing orders to flood even in the event of an attack. That would have to come from higher headquarters.”

That was a relief. Geier made mental note to cut the telephone lines into the building. The Abwehr knew that the Dutch knew that hundreds of thousands of Germans were massing close to the border, and accordingly feared that standing flood orders might have been issued. Still, he glared at the Dutch sergeant and ordered him to take them to the control room. They descended a deep flight of stairs against the left wall of the room, and found themselves at a thick steel door which the sergeant unlocked.

They were in a small chamber -- illuminated by a single bare lightbulb, and slightly damp. Around the walls and in the center of the room were large metal boxes vaguely resembling upright pianos. Each one had an assortment of gauges and valve wheels across its surface.

“Are these the hydraulics?”

“Yes, Majoor. Each one of these controls one of the river gates. All six gates can be opened in less than five minutes.”

Geier inspected each one carefully. “Are there any other control points?”

“No, Majoor. These river-gates may only be opened from this room.”

“And they do not look like anyone has been tampering?”

“No, Majoor.”

“Good.” The six of them paced back up the stairs to find three of the sergeant’s companions sitting around their mess table, drinking tea and eating slices of bread.

“Majoor.” It was van Driel, in the process of lighting a cigarette. “Then are we to take it that everything is normal? There were clearly no signs of sabotage.”

“Yes.” Geier turned to the sergeant. “See to it that in the future at least two of your men are awake at all times, with the other three free to rest or sleep.”

“Without fail, Majoor.” The sergeant saluted.

Geier felt a sudden jolt of adrenaline. The sergeant. The three men at the table. Two plus three is five. One plus three is four. “Wait!”

“What?”

Geier raced across the room, scanning every corner. The bathroom was empty. There was no one left in the control room. Someone was missing. “Someone’s missing!”

In a fluid blur, Soll raced across the room and threw open the door. He bolted out into the night, followed closely by Ascher. Geier heard a muffled yell, but couldn’t follow them out to investigate.

“None of you move.” He wheeled on the remaining four Dutchmen with his Menta. He was into this at full depth now. “Slowly get up, with your hands in the air, and each one of you line up against the wall. One sound and you’ll all be shot.”

Eggers had drawn his concealed pistol as well. As the Dutch soldiers backed numbly against the wall, van Driel advanced on them hungrily with a long length rope. He tied each man’s hands behind his back and then tied them all to a large stovepipe against one wall.

“Get the explosives, now, both of you. I’ll watch the prisoners.”

Within ten minutes, the two Dutch fascists had returned with the explosives they had hidden nearby. Just as they descended to the control room, Soll and Ascher stumbled back into the building, badly winded. Soll was wiping his ankle-knife with a handkerchief.

Geier soon got out of them that Soll had sprinted after the fleeing private on foot. “When he was getting ahead I stole a bicycle even. I pedaled after him as fast as I could, but he went off the road into a sunken field, and I had to start back after him on foot. He disappeared twice, but at last I overtook him and pinned him down long enough for Ascher to arrive. He’s all taken care of. I don’t think anyone heard.”

“Good.” Geier felt relief sweep over him at such nearly-averted catastrophe. “The others just took the explosives below.” While the two skilled Germans went below to set the charges, Geier ordered van Driel and Eggers back out into the night to complete the second phase of the operation.

In twenty minutes, they returned. In the fields around the Roost-Rhenen flooding station, they had placed landing markers for the gliders of the small detachment of assault pioneers who would wreck the river gates themselves and then protect Geier and his men as they exfiltrated to advancing German lines.

Geier ordered the fuses primed. They would wait until they had the protection of the glider men before blowing the charges. The night was wearing on. Three twenty. Geier posted van Driel and Eggers outside to watch for the approach of the gliders. Three thirty. Three forty.

“Here they come!”

A hoarse whisper from van Driel sent Geier racing outside. He trained his gaze where the Dutchman was pointing. In the distance, four dark shapes were flying silently over the field on the other side of the river. They were moving slowly, in a shallow glide over the outer works of the Grebbe Line. No searchlights lanced up to meet them, no gunfire broke the darkness. At last, they were so close that Geier could distinguish the heads of pilots in the cockpits. They soared over the flooding station no more than a dozen meters off the ground, silent as a flock of birds.

The four gliders landed some distance away in a darkened field. Geier didn’t see any soldiers pouring out yet. He wished that they would hurry.

The beam of a flashlight coming up the road toward the flooding station drew his attention. A kapitein of engineers was walking his bicycle slowly toward them.

“Follow me and say nothing,” Geier hissed, beginning a series of long, confident strides toward the Dutch officer.

The man stopped in his tracks when he saw the three men approaching.

“Hallo, what is your business out alone at this hour?”

“There were reports of sounds of shouts or an altercation near the flooding station some time earlier tonight. I was sent to investigate.”

“Actually we were sent to investigate. It just seems that one of the non-commissioned officers posted here injured himself slightly in the night. A doctor is seeing to him now.”

The Dutch officer leaned his body first left, then right, seemingly trying to look past Geier’s body at the door to the building. “May I just take a look inside to confirm that everything is in order, then, Majoor?”

“I do not think that that is permissible. With the increased security here at present, I would need to see a written order from your commanding officer.” Geier sensed that the man would buckle soon.

“Halt! Lock!” All four men snapped their heads to the right, where three men wearing strange helmets had emerged from the bushes and were pointing submachine guns at them.

Geier gulped. “Key.”

“Which one of you is Geier?”

“I am.”

“Are all these men actually German?”

“Only me, but --”

In a startling second of gunfire, they had shot the others dead. Geier whirled, pointing furiously at the bodies of Eggers and van Driel. “No! Those two were our Dutch friends!”

“I’m sorry.” The Feldwebel brashly raced past Geier and opened the door to the flooding station. A dozen more assault pioneers had appeared, most of them pouring into the building. Geier simply stood there bewildered until a lieutenant approached him and saluted.

“This is Hauptmann Heilmann.”

A Luftwaffe captain with a haughty face paced up to Geier and saluted as well.

“What is the meaning of this, Hauptmann? Your men shot two men working for the Abwehr! And fired without being first fired upon!”

Geier saw the captain’s jaw clench grotesquely in the moonlight. “Accidents happen.” With that, the man spun on his heel and walked back into the flooding station.

Following him, Geier found Soll and Ascher coming up the stairs from the control room. “All the charges are set, Herr Geier. Two minutes to get out.”

Geier urgently passed the word to the assault pioneers, who began taking up positions around the building. The four Dutch prisoners were gagged and thrown out into the road in a heap.

At last, a lone assault pioneer charged up the stairs from the control room. “Thirty seconds! Get out, get out, get out!”

The men waited in the ditches around the building with bated breath. Then, a thunderous clanking rumble emanated from the bowels of the flooding station. Light smoke lazily wafted through the slit in the closed door.

Geier could hear alarms sounding in the distance. He made his way down to the concrete flooding outlet just upriver from the building. There, he saw a squad of assault pioneers working to wreck the river-gates. Several fierce and sparking points of light burned in the flooding outlet -- searing white-blue, and brighter even than welders’ arcs. He returned to find many of the assault pioneers back inside the flooding station.

He was pleased to find them moving the three bodies inside and covering them with sheets. The men looked terribly pale in the light, their faces glistening and tense.

Geier heard a faint thud, and the landscape outside was bathed in ghostly white light.

“Flares!” Hauptmann Heilmann shouted. “Get the men back inside as soon as they are done!”

The pops of gunshots immediately sounded in the fields outside the flooding station -- then barked orders from the officers.

Someone turned out the light inside the flooding station and the men within trained their weapons through the windows. The others -- there seemed to be about thirty in all -- were digging in around the building in what cover was available. Two of them came in through the door and set up a water-cooled machine gun in one of the windows. Geier saw that the hands of the gunner seemed to be twitching slightly. He hoped there would be no further friendly fire.

More pops in the fields. From his position, Geier couldn’t see what was going on there, but it didn’t sound terribly serious. Then frantic screams. “A whole lot of them! Help! Help!” Gales of automatic weapon fire continued for almost a full minute.

Then one of the soldiers near Geier at the window pointed toward the gully down the road where the van Driel had hidden the markers and explosives. “More of them!” The flares had burnt out, so the area was again too dark for Geier to see anything.

In a moment, the machine gun opened fire, strobing yellow light onto the gully. Bright tracers snaked from the barrel, dousing the low ground with bullets. In the flickering light of the muzzle flash, Geier could make out helmeted shapes crouching for cover.

Another flare blazed to life above them, revealing more helmeted shapes all around the flooding station.

The assault pioneers fired at them frenetically.

Heilmann paced back and forth at the center of the room, encouraging his men. “Keep firing, keep firing! Still more than an hour until morning.”