TC Pilot & vadermath - Yes, it was an interim originally by Calipah, way back when... its in the Table of Contents.

4th Dimension - My plans in this story are NEVER evil... :rofl:

Bagricula & RGB - 1) William of Ockham will make a cameo, simply because I think he is awesome.

2) There isn't necessarily going to be a holdup in scientific development and thought. As this is an alternate history, Maimonides has been lost as a philosopher, but someone else could have always stepped into his intellectual place. That said, things have already developed differently enough that the chances of philosophy and science evolving in the same places and manners is virtually nil. There are huge beacons of learning in the Komnenoi Empires, but also there is undoubtedly a great deal of stagnation...

Laur - I have to agree, there are actually people the Komnenoi have been far more honorable than. So far. Partly its because their empire so far was strong enough they could settle internal disputes without calling on someone else's assistance...

Partly its because their empire so far was strong enough they could settle internal disputes without calling on someone else's assistance...

armoristan - So glory tastes like a Greek boot?

And yes, update is done!

“Sisak was the day I-ran was born.” - Nur al-Din Ni’mat Allah, Persian poet and philosopher, 1368

April 17th, 1286

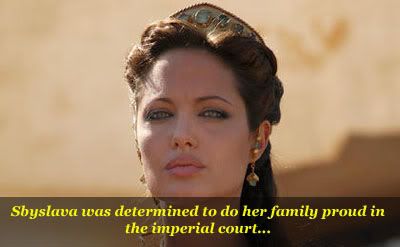

Sbyslava Mstislavna blinked, unable to believe her eyes. She’d heard Konstantinopolis was the Jewel of the World, but when she’d heard that phrase the first time, they’d been mere words. Smolensk was no backwater—it was a fortified town of 10,000, with a magnificent stone cathedral with a gilt roof and palaces that were the envy of boyar and jarl alike. Outside the King of Sortmark, her father was the most powerful man south of Novgorod. Sbyslava was used to furs and silks.

But this…

She blinked again, a riot of brightly painted and gilt roofs catching the sunlight and momentarily blinding her. Below that shimmering sea hung the whitewashed hulk of the Seaward Wall, its towers arrogantly thrusting towards the sky. Around them was a sea of ships—merchants from all corners of the world, dromons of the Imperial Fleet, private pleasure craft floating hither and thither. It was too much for the eyes to take in!

“It’s beautiful, isn’t it?”

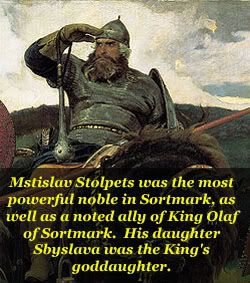

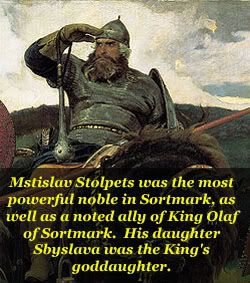

Sbyslava turned to the voice, and smiled up at her father. Prince Mstislav of Smolensk, too, was staring across the water to the approaching city. He was a tall, powerful man, called Mstislav Stolpets—the Little Tower, a pillar of politics north of the Black Sea. Here, however, before the towers, domes and glitter of the Capital of the World, he seemed small, old, and weak.

“It’s amazing, papa,” she said quietly.

“Have you practiced your welcome greeting?” he asked calmly. Mstislav had risen to become the preeminent lord in Sortmark not just through his intimidating presence and brute force. He was also known as Mstislav Liciy—Mstislav the Fox. The Prince’s father had knelt to the Danes only through force of arms, and there was always tension between the Danish jarls and the Russian knyaziy. Mstislav’s powerful seat made him a spokesmen for the Rus, and his clever tongue made him a friend of King Olaf—so much so that Sbyslava was the king’s goddaughter.

“I have papa,” Sbyslava nodded, and indeed she had. Those simple, few words she would say while she stood on the docks could set the tone of how her future husband would think of her, and how the nobles of the Empire would treat her. She’d chosen her words cautiously, carefully—she would only have a single chance.

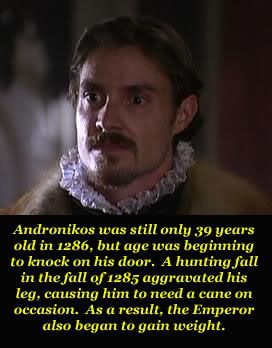

The Emperor, they said, was a moody man—though they said many things about him, including that he was growing larger and now needed a cane. He’d lost his first wife tragically in childbirth. Sbyslava refused to believe the rumors about his second wife—she simply couldn’t fathom a man who would murder his wife when so much was at stake. It might have been two years since her tutor Gennadios spoke of the nations around Sortmark, but Sbyslava knew the King of the Germans was a powerful man. The Romans were strong, but why would someone pick a needless fight? Maybe there was something else going on? Maybe his last Empress simply died? Sbyslava nodded to herself—that had to be it. The simplest solution was often the best, she’d decided.

So she couldn’t seduce him—not that she had much experience at seduction anyways. One of her handmaidens had made quick work of a few guardsmen, but Sbyslava knew an Emperor would have far different tastes and needs than a guardsman looking to rut in a stairwell. Especially an Emperor who’d lost someone he loved long ago. Her eyes narrowed as the boisterous harbor swelled into view. All along the shore were an array of shining armor and massive plumes—if her mind hadn’t been focused, she’d have had to blink yet again at the sight.

Yes, in the midst of that panopoly, she saw him. Only the Emperor of the Romans would be clad in such resplendent robes, a crown of gold circling his brow with pearls hanging from the sides. He wasn’t as plump as she’d heard—not thin, but not fat. However, his hand rested discreetly on an ivory tipped cane. She couldn’t fully see his face, but she couldn’t help imagining he was frowning sternly at her.

No, words would not be sufficient, not by themselves.

Sbyslava smiled, a big broad array of teeth that complimented her well. She knew he could see her. Gingerly, she reached down, towards the lyra sitting on the ship’s deck. It was a clumsy looking instrument to her, nothing like the flute she knew from home. She would learn it—and anything else she could that’d please her future husband. It would be the best way to safeguard herself, her future children, and her family far away.

“It’s called the Oak and the Dove,” her father reminded carefully. “His favorite…”

“I’m not a fool, papa,” she smiled nervously. Her mind ran over the plan yet again. She would walk off the ship, playing the song she’d practiced for no less than six weeks constantly. Then, she’d bow, and say she hoped it pleased him, and offer him condolences. She would then say she would do whatever he required, and be his true and loyal servant…

…she hoped it’d work.

“I am simply reminding you, for my sake,” Mstislav said with a gruff grin, before wrapping an arm around her shoulder. “You’ll do well, Sbyslava! You’ll make us proud!”

“I will, papa,” she affirmed, her hands gingerly touching the strings.

==========*=========

June 23rd, 1286

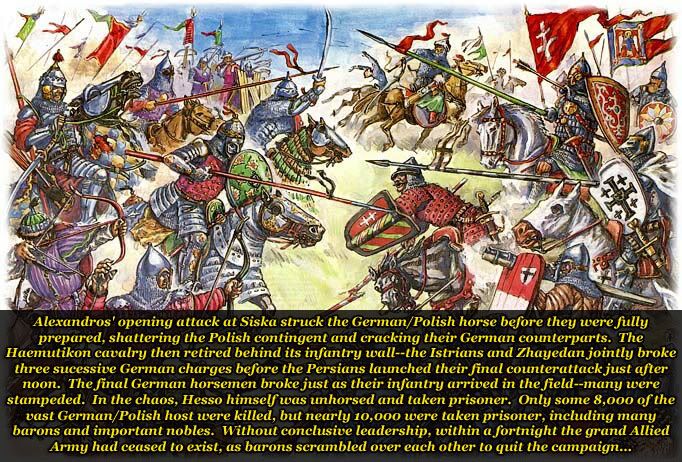

Outside Sisak, Theme of Croatia

Makarios Ioannopoulos reined up his horse next to the small copse of officers and nobles, and stared out at the field ahead of them. In the distance, a sea of horses, men, banners and spears swaying on the march or rocking with a horses’ walk—all danced lazily in the hazy early morning sunshine. Hesso had come, with the full might of his empire behind him.

“Exciting day ahead,” Makarios said grimly, casting a glance to his left. There, Basilieus Alexandros II of Persia sat sternly on his own charger—a mouse of a man on a giant animal. A mouse with a deadly bite, the Germans would soon find out.

“Probably,” the King responded. Before battle, Alexandros was cherubic, laughing, giggling, excited about the danger to come. But now, just on the eve of battle, he was all business—stern, focused, eyes never wavering from watching his opponent’s slow deployment with the gaze of a hawk. There would be plenty of excitement to come.

Makarios urged his horse forward, till he was next to his Lord—excitement was not his forte. He preferred operations that went smoothly, plans that unfolded with no problems—no unexpected surprises, no daring against long odds. He’d had plenty of that during the attempts to get the army to the Balkans.

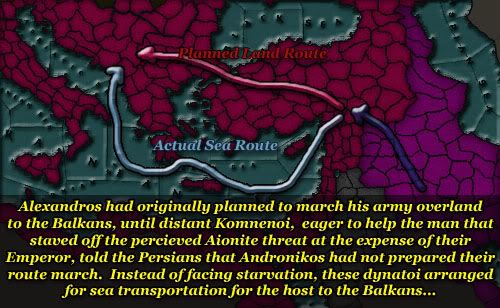

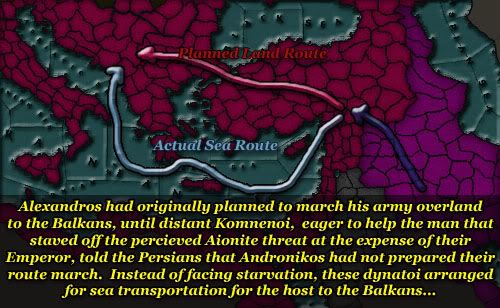

The Persian force first marched into Syria, intent on making its way by land across the Empire proper. However, when Prince Simon Komnenoedessa with the Basilieus and his commanders near Nisbis, he told Alexandros that his cousin Andronikos had made no provisions whatsoever for the Persian army to gain food during its journey. Edessa had been in the Persians debt—after all, it was Alexandros who drove the Aionite threat away from the Near East before it could spread to Syria proper.

Instead, the Komnenoedessas and their even richer neighbors the Chrysokomnenoi lumped together funds (coupled with a few loans from merchant guilds keen to keep the Mediterranean a peaceful Roman lake) to ferry the King and all 18,000 of his Persians across the waters, and safely to Ragusa. By luck, neither storm nor tide struck the Persians down, and the backbone of the army arrived safely in Ragusa during the first weeks of May, 1286.

“They’re coming straight this way,” Makarios grunted, squinting in the sunlight. He couldn’t see how many banners there were—save that there were many. The Spahbod looked behind himself for reassurance. The four vashti lay behind the hill, with the bloody Balkan thematakoi, the only remaining parts of the former Haemutikon left behind, were arrayed on the hill’s crest.

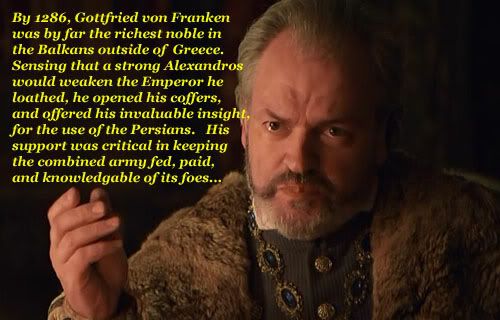

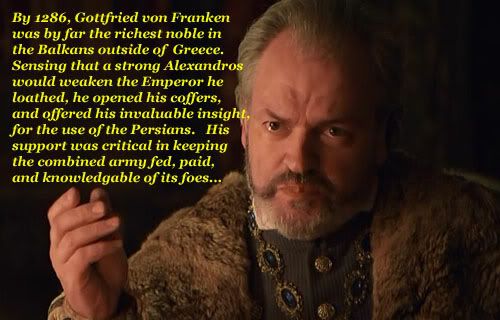

Makarios snorted. Everyone plainly knew it wasn’t the Danes that made Andronikos pull the two professional tagmata from the Haemutikon at the last minute—it was politics. Andronikos wanted them to fail. The Imperial grain monitors in Croatia proper were as useful as toads—and the peasants weren’t keen to surrender their food to Alexandros’ men. The local dynatoi helped some—the Princes of Serbia, and the Imperial City of Ragusa donated some money to the expedition, but not as much as hoped. An unexpected boon came from the rich Prince of Istria—Gottfried von Franken’s coffers were deep, and his generosity unexpectedly large. Everyone assumed it was because of his surname—Hesso Arpad, should he gain the lands of a von Franken, would surely confiscate them in order to ruin the closest dynasty rival to the German throne.

Yet the more Makarios spent time with the man, the more he was convinced that Gottfried von Franken was motivated more by opportunism than anything else. The man loathed Emperor Andronikos, and continually placed ideas before the council of war that should the Germans be defeated, the army should march north and begin despoiling the German countryside. Regardless of his motives, his deep coffers and filled granaries helped to alleviate some of the problems of fodder for the enlarged Haemutikon Stratos.

But food was only the start of the problems—so was the quality and number of men. Alexandros’ small core had been augmented by “tagmata” from no less than five themes and the Imperial City of Ragusa. On paper, it was a princely force—some 25,000 or so added to Alexandros’ rolls. All those soldiers had to be fed somehow, however, and more importantly, some of them were more hungry mouths than veteran soldiers.

The Croat contingent had been useless—Mother Church kept only enough men on retainer to stop bandits and other ne’er-do-wells, but no more. Neither did the Church have any decent contact with sellswords to fill the gap. The Serbs and Epieroites at least were usable as light infantry in a pinch. In fact, only the Ragusan detachment of mercenaries and the Istrian thematakoi showed up equipped like a proper army—three tagmata strong in total, enough to be useful.

“Looks like all of Hesso’s bloody cavalry,” Prince von Franken hissed. The man looked awkward on the saddle—he leaned towards the rotund side, his finely kept beard no doubt hiding a double chin. Yet his armor was finely made with black enameling with gilt trim. Only the Basilieus’ own white enameled masterpiece, complete with a shield bearing the double-headed lion of Persia, could outmatch the Prince of Istria in the morning light.

“That’s all of them,” Marzban Shirazi nodded grimly.

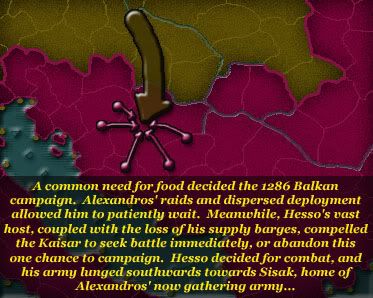

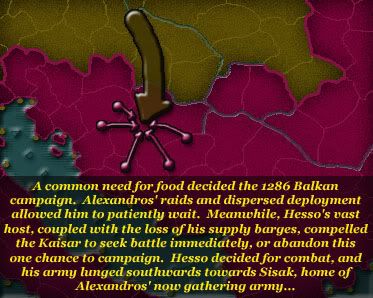

There was plenty of reason to be grim—the Haemutikon was low on food, low on money, and facing a force thrice its size. There was only one silver lining in this sea of darkness.

The Germans wanted battle as quickly as possible too.

Hesso had lumbered across Hungary with both of his armies, every man he could spare. The host was huger than Alexandros had been told—Shirazi’s scouts guessed there were as many as 30,000 cavalry alone, including some 10,000 mounted knights. Each man in shining mail dragged along with him peasants and retainers. Makarios had no doubt the final host was easily greater than 80,000—even more once the Poles joined the horde.

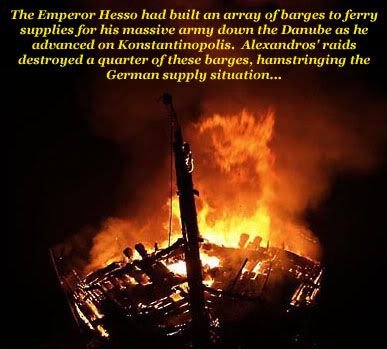

Yes, the Haemutikon Stratos had some 30,000 mouths to feed, but the Germans had twice as many, and pillaging the countryside only got one so far when the army was that vast. Hesso and his men had planned to ship food down the Ister using barges—a fine idea, straight from a Roman textbook—but Makarios’ Persian light horse three weeks before had raided north, crossed the Ister near Sirmion, and captured a number of the barges. The ones he and his men couldn’t board and float to the other side of the river, they burned. There was no telling how many of Hesso’s food ships they’d stolen or destroyed, but it’d certainly eased their own suffering.

The effect on the previously plodding German force was equally apparent. The Germans hastily threw pontoon bridges across the river to the west of Sirmion, then plodded across with all the speed of a stumbling elephant. Makarios smirked, watching as the horde pressed forward. Hesso’s barons were undoubtedly angry and embarrassed at the raid, and the kerns would be crying hunger and wanting to go home. The German King had only a few weeks to force a victory, and the sand was passing through the glass. The Germans lumbered forward, their attempts at speed conflicting with their size. The end result was a confusing mess, ponderously moving through the countryside.

Shirazi had only worsened the German’s predicament—Alexandros concentrated the thematakoi from the Princes on him, but spread out his own professional troops, with posts set up for riders to bring messages back and forth. It helped him ration out what fodder he could. While Makarios’ men raided barges, Shirazi and his horsemen crossed the Danube, sniping at the German’s sides, moving just slow enough the lumbering horde could follow, but just out of reach.

“It’s like leading a puppy along,” the King smirked, watching the oncoming mass of men, animals, wagons and dust. Makarios had to agree. The lands immediately along the river had once belonged to the Church, but the Metropolitan overseeing the region left its defense in the care of none other than Gottfried of Istria. The Prince had no compunction about ruthlessly ordering all the villages within five miles of German scouts cleared, the cattle slaughtered, the crops burnt.

It wasn’t his land, after all.

As the huge German and Polish army stumbled onwards, it had only one place it could go—Sistak, site of the major granaries in the province, a town built around the food storehouses that supported the peacetime Haemutikon. The Germans, tired, angry, hungry and looking over their shoulders to home as much as they looked forward, clamored forward. The peasants, the backbone of any siege, had to be going hungry—Istria’s men had cleared the surrounded land well, Shirazi’s riders nipped at the flanks. Five days before Alexandros sent his riders out, ensuring the last of his dispersed men arrived the night before. Now, the Persians and the thematakoi stood in the morning sun, already arrayed for battle as their enemies stumbled forward in a long, strung out mass.

The head of that enormous snake glittered in the morning sunlight before them—the core of the German and Polish cavalry, including Hesso’s ten thousand knights. Makarios knew the numbers—Shirazi’s scouts guessed there were 30,000 horsemen altogether in the leading contingent of the mob. These were the best fed, best armed, and best led of the German horde—they were the power, the heart of the motley army.

Bugle calls echoed distantly over the hills of Croatia. Slowly, the vast German horse deployed as best it could in the rather narrow fields. As he watched, the Spahbod nodded. Hesso’s plan of battle was obvious—he was launching a headlong attack. Shirazi’s men were right—the Germans were beyond hungry. They were ravenous, and Hesso could not lay siege to any castles, let alone the likes of Zadar or Ragusa, without his levies…

“They’re a mess…” Makarios said to no one in particular. Von Franken had helpfully provided a great deal of information on the banners used by the armies they would be facing—from the white and red eagles, it looked like the Poles were being shunted to the left. Some of their men were adamantly riding to the center, even as a yellow banner with a red lion on it pushed back. Makarios frowned, trying to wrap his mind around the German name. Habspurg?

“An utter disgrace,” Alexandros hissed, squinting. For a second, Makarios saw something familiar in the Emperor’s eyes—calculation, thought, the same look he’d seen countless times in the hills of the Zagros, the deserts of northern Arabia, or the marshes of Mesopotamia. Calculation, conclusion…

“Orders!” Alexandros barked. “Shirazi, Reza, Georgios!” he called cavalry leader to him—all his Persian officers, as well as the chief of Istria’s cavalrymen. The commanders trotted closer, as Alexandros finally nodded to Makarios as well. Ioannopoulos cast a longing look back at the well-prepared ambush behind them—he knew what was coming.

“Subtlety, Majesty!” he called, before the Emperor could even speak.

“No subtlety necessary!” Alexandros countered sharply. “Their deployment is a mess, their cavalry have no support! Once the nobles are routed off, the foot rabble behind will flee, and we’ll run them down!” The King turned to the Princes and Shirazi. “We’ll kick the head of the snake and kill the whole thing! Hesso won’t expect that! Look at that mess!”

Makarios looked up again—the entire mass had stopped, and a frantic array of bugle calls echoed back and forth. He swallowed—they were confused. If they arrayed that host, things could turn bad. If that host kept coming, disordered as it was…

“Shirazi, take your horsemen, and ride at them hard,” Alexandros was saying. “Shower them with arrows, insult them, whatever you must, but make them charge before they get ordered. Understood?”

“Yes Great King.”

“Go,” Alexandros waved. As Shirazi turned, whistled for his men and began calling orders, the Emperor went on for the rest. “The rest of you, form your cavalry on me, and send the light foot to the rear—flanks of infantry we already have waiting. Should we not break them, we’ll rally behind the foot, yes?” The Basilieus cast a look at Makarios, and a thin, stressed smile briefly crossed his lips. “Rest easy, I haven’t completely gone insane, Spahbod.”

“Thank you, Majesty,” Makarios nodded. The Alexandros II that Ioannopoulos knew had four basic strategems that were constantly reused, tweaked for this circumstance or that.

Charge it and kill it.

If the enemy was too strong to charge directly, use speed to wear them out—then charge them and kill them.

If the enemy was spread out, charge their detachments and kill them, if he was concentrated charge him headlong and kill all of them. Above all—charge them and kill them.

It’d worked before—calculated aggression that the enemy didn’t expect. Confusion, surprise, and disorder among the enemy were worth 10,000 cavalry.

Makarios began yelling orders to his men, and the Anusiya trotted from its former place of hiding up to the front in a formation that would have done a parade ground proud. Ioannopoulos smiled when swore he heard von Franken make a disparaging remark that the Basilikon in Konstantinopolis never looked so good. In the ten minutes the Spahbod’s men needed to deploy, Shirazi’s had ridden forth on their mission. When Makarios looked up finally, shield at his side, the mass of Persian light horse was already thundering back—an enormous pall of dust behind them.

The Germans were coming.

Makarios forced himself to remain motionless, steady as the light horse galloped through their lines. The Spahbod kept his mind busy eyeing the distance—he hoped the Basilieus would wait until the Germans were only two hundred yards off before ordering his…

“Anasuyi vashti!” Alexandros bellowed, hand finishing the clasp on that lavender cloak, “Ala El-Sayif wal Hurba!” The King spun his horse around, and before Makarios could shout a warning, the Basilieus barked to the Istrians in Greek the same command.

“Kataphraktoi, ready kontos!”

Metal scraped, and the diminutive Lord of Persia drew his father’s blade. Steel shimmered in the morning light as Alexandros started to trot, then canter down the length of the cavalry line..

“Majesty, shouldn’t we...” Makarios started to yell…

“Charge line! Charge!”

And then Alexandros wheeled his horse and was gone, purple cape flapping in the wind, his sword aloft as he galloped headlong towards the throng ahead. Makarios looked to the left, then the right—the marzbans and strategoi sat blinking, stunned. The men gaped as their King galloped on, alone. For a moment, Makarios was with them in stunned silence, before training and previous experience finally kicked in. A second later, his own sword was out.

“Protect the King!” Makarios screamed, spurring his horse. The motley host behind him echoed the call, and the so-called Haemutikon Stratos charged headlong into legend.

May 19th, 1287

Outside Orleans, France

“It’s only a scratch!”

It’d taken Prince Nikephoros a full three weeks after his arrival in Spain to find his ‘battle voice’—the bellow that could be heard above the clash of arms, the call that would steady men’s hearts. Pandomestikos Godwinson’s was like a thunderstorm, huge and menacing. Nikephoros knew his was different—reassuring, encouraging, not raging furious. Yet despite that voice, he bumped and jostled as the litter carrying him trundled onward through the disheveled morass of a battlefield.

France was not supposed to be this way.

For years, the Western armies had existed, been trained, for one purpose and one purpose only—to fight the French. The first part of 1286 had gone smoothly—Godwinson split his force into three taxarches, and an early spring thaw meant his men were over the Pyrenees by April. As the knights of France were marshalling in May, Godwinson was actually adding the feudal levies of Aquitaine and Toulouse to his own forces. The Romans were in position, ready, and the French had no idea what awaited them.

“I said put me down!” Nikephoros yelled again. He tried to raise his left hand to feel the side of his back where the arrow had struck, and he cursed as it moved sluggishly. Not now, not now! Nikephoros blinked, then tried to turn to look back at where he’d come from. In the distance, he could hear drums and horns, but he couldn’t turn around enough to see. One of his litterbearers slipped in the mud—the Prince felt a lurch, and heard an Occitan curse.

It was the mud that did them in. The first three weeks of June were filled with constant rain—buckets and buckets that fell from the sky in an endless torrent. The rivers swelled, and the roads began mudpits. The wagons of the Stratoi couldn’t move—and so the entire Roman war machine ground to a halt, just days before it was to launch its northern march, starting perhaps the largest ambush in history. Instead of catching the French unawares as Godwinson had hoped, it was the French, by some miracle, luck or perverseness of fate, that managed to hobble out of the mud first.

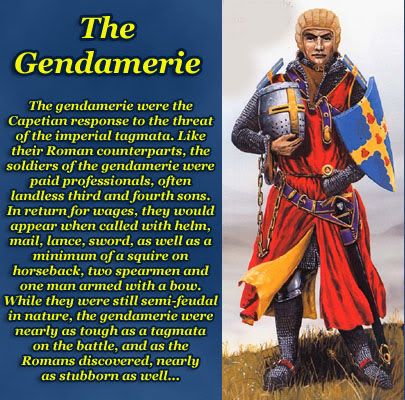

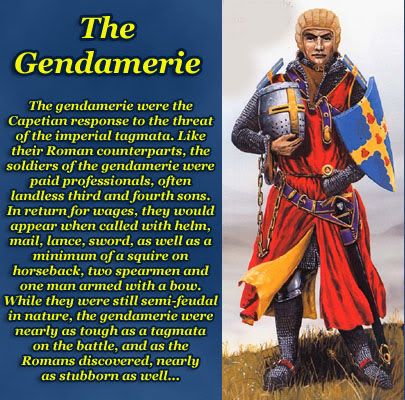

First blood was taken outside of Limonges—Nikephoros’ bandarches came upon a French detachment besieging several local castles. The fight was ugly and short, and the French did surprisingly well, holding their lines until nightfall and extracting a steep price from the Roman men, especially the thematakoi. It was the first time the Romans ran into a group of gendarmes, and it wouldn’t be the last.

Finally the litter crossed some unbidden threshold into the disheveled Roman camp. Nikephoros could see tents, pennants from the corners of his eyes, and he heard voices, shouts, calls. They were jubilant. Nearby, a trumpeter repeated some distant call—three short blasts.

Pursuit.

“We won?” Nikephoros tried to sit up. Once again, the silent, unbidden weight made his left side hang lower. He struggled with it for a moment, before craning his neck, trying to see above the cheering soldiers and the raised swords about him. A chorus of calls greeted his question. Bragging and congratulations filled the air.

The French were running finally.

As Nikephoros unwillingly made his way back to the churigeons, he pieced together what’d happened since his desperate, pell mell attempt to blunt the French threat. After a French arrow took him down, his horsemen evidently had smashed through the French flank, directly behind those stubborn gendarmeries that had broken thematakoi and line tagmata alike. While the French levies broke and ran, those three units coldly held their place, covering the French retreat. On another day, the Romans would have tried hard to crack them—but Godwinson’s victory had come at a high price.

Pandomestikos Godwinson himself had been wounded—he’d been in the front, as was his way. No one could tell Nikephoros where the old man was or his health, only that he’d been cut off momentarily and surrounded, only to hack his way back to friendly lines. They said his axe had been covered with French blood—and on the morrow, the armies swords would do the same. The French would break, the brave men promised. They must on the morrow.

But Nikephoros knew there’d be no tomorrow. Just like outside Limonges, the skirmishes around Poitiers, and the previous big battle near Gueret, the French would pull those precious men out during the night at the latest, and in the morning those men would be the rearguard as King Hugues and his nobles rounded up their scattered men. The French army battered, it was bloodied, but it was not destroyed.

The exact same as its Roman counterpart.

Instead of a quick and crushing victory, there was a slow, bloody waltz to the north. Godwinson’s columns would pursue, only to come across the French reformed elsewhere, stubbornly fighting, extracting another butcher’s bill. For 18 months it’d gone on, through the mild winter and into this spring. Nikephoros was jealous of his cousin to the east—as dispatches came from Alexandros reporting first Pest taken, then Praha, Nikephoros had been forced to say his men had tangled with another French force indecisively, or that this small town or that castle had finally been taken. To add insult to the injury, of course the dynatoi of Greece, once so reluctant to deploy their thematakoi, were now stumbling over themselves to send men north, for loot, if nothing else.

Finally the Prince saw the roof of a tent over his head. He didn’t need to smell the foul stench or hear the moans of the wounded to know where he was.

“Put him on the table,” the man gruffly ordered. Nikephoros felt a brief stab of pain as the littermen set him down as gently as possible. Just as quick as it came, it faded to something else—something dull. The Prince saw the churigeon’s shadow, and heard him grunting and muttering as the littermen shuffled away to fetch more wounded.

“It’s only a scratch!” Nikephoros loudly protested one more. He knew an arrow had hit him—he’d felt the sudden slap on his side. He knew he was bleeding. But for the love of God he didn’t want the churigeons seeing it! That side had always been a little numb, but now…

The dull ache was starting again. The Prince tried to sit up, but the churigeon’s hand clamped down. He laid back, all manner of curses coming into his mind.

“It’s not a scratch, Highness, ‘tis an arrowhead in your side!” the chirugeon hissed. “Now, lie back down and let me examine it!”

Nikephoros sighed, and did as he was asked. He felt poking and prodding—somewhat distantly. Sweat was pouring off his brow. Someone undid the clasps that held his mail over his side. Linen and cotton ripped.

“My God….”

“What?” the Prince looked over, trying his best to look naturally confused, even though he knew it was too late.

“Oh… it’s…it’s… this rash…”

Nikephoros nodded slowly, paling. He’d first noticed the thing at the start of the campaign—a white patch on his skin that felt strangely numb. He’d had them before—he noticed the first two years earlier—and he’d taken great pains to keep them hidden. Nikephoros had a voracious appetite for scrolls and books, and he feared not just what the churigeons would say it was, but what the results could be…

“What rash?” the Prince tried to sit up. He halfway slumped in the effort, but he pushed himself up far enough to stare the churigeon in the face. The man’s eyes were wide, as he stared down at the light patch of skin next to the bloody barbs of the arrowhead sticking cruelly out of his flesh. In another circumstance, Nikephoros would have smiled—Godwinson had said his chain shirt was finely made. It and the cotton gambeson underneath had taken most of the hit. The arrow wasn’t in very deep at all, but the wound was still bleeding all over the table.

But here, now, with his secret on display, there was no time for a grin. Not when his succession was on the line!

“H…Highness?” the churigeon asked quickly.

“You see no rash, doctor,” Nikephoros hissed, coldly spelling it out for the man. He glared at the man’s assistants. “Neither do any of you. Get the arrowhead out. I need no alcohol, nor a cloth to bite.”

Several of the assistants paled.

“But Highness…”

“You will say I have a high tolerance for pain, is that understood!” Nikephoros hissed. “Now get that thing out of me!”

Another long one! Alexandros as expected beats the Germans to a pulp, while in the West, Roman fortunes are not as ascendant. Alexandros’ success means he, as well as numerous dynatoi from the Balkans, are stuffing their pockets with loot from Pest to Vienna—undoubtedly a threat to Konstantinopolis. How will Andronikos respond to this turn of events? What is Nikephoros’ mysterious ailment, and will it remain a secret? What’s next for the Victors of Sistak? More to come, when Rome AARisen continues!

4th Dimension - My plans in this story are NEVER evil... :rofl:

Bagricula & RGB - 1) William of Ockham will make a cameo, simply because I think he is awesome.

2) There isn't necessarily going to be a holdup in scientific development and thought. As this is an alternate history, Maimonides has been lost as a philosopher, but someone else could have always stepped into his intellectual place. That said, things have already developed differently enough that the chances of philosophy and science evolving in the same places and manners is virtually nil. There are huge beacons of learning in the Komnenoi Empires, but also there is undoubtedly a great deal of stagnation...

Laur - I have to agree, there are actually people the Komnenoi have been far more honorable than. So far.

armoristan - So glory tastes like a Greek boot?

And yes, update is done!

“Sisak was the day I-ran was born.” - Nur al-Din Ni’mat Allah, Persian poet and philosopher, 1368

April 17th, 1286

Sbyslava Mstislavna blinked, unable to believe her eyes. She’d heard Konstantinopolis was the Jewel of the World, but when she’d heard that phrase the first time, they’d been mere words. Smolensk was no backwater—it was a fortified town of 10,000, with a magnificent stone cathedral with a gilt roof and palaces that were the envy of boyar and jarl alike. Outside the King of Sortmark, her father was the most powerful man south of Novgorod. Sbyslava was used to furs and silks.

But this…

She blinked again, a riot of brightly painted and gilt roofs catching the sunlight and momentarily blinding her. Below that shimmering sea hung the whitewashed hulk of the Seaward Wall, its towers arrogantly thrusting towards the sky. Around them was a sea of ships—merchants from all corners of the world, dromons of the Imperial Fleet, private pleasure craft floating hither and thither. It was too much for the eyes to take in!

“It’s beautiful, isn’t it?”

Sbyslava turned to the voice, and smiled up at her father. Prince Mstislav of Smolensk, too, was staring across the water to the approaching city. He was a tall, powerful man, called Mstislav Stolpets—the Little Tower, a pillar of politics north of the Black Sea. Here, however, before the towers, domes and glitter of the Capital of the World, he seemed small, old, and weak.

“It’s amazing, papa,” she said quietly.

“Have you practiced your welcome greeting?” he asked calmly. Mstislav had risen to become the preeminent lord in Sortmark not just through his intimidating presence and brute force. He was also known as Mstislav Liciy—Mstislav the Fox. The Prince’s father had knelt to the Danes only through force of arms, and there was always tension between the Danish jarls and the Russian knyaziy. Mstislav’s powerful seat made him a spokesmen for the Rus, and his clever tongue made him a friend of King Olaf—so much so that Sbyslava was the king’s goddaughter.

“I have papa,” Sbyslava nodded, and indeed she had. Those simple, few words she would say while she stood on the docks could set the tone of how her future husband would think of her, and how the nobles of the Empire would treat her. She’d chosen her words cautiously, carefully—she would only have a single chance.

The Emperor, they said, was a moody man—though they said many things about him, including that he was growing larger and now needed a cane. He’d lost his first wife tragically in childbirth. Sbyslava refused to believe the rumors about his second wife—she simply couldn’t fathom a man who would murder his wife when so much was at stake. It might have been two years since her tutor Gennadios spoke of the nations around Sortmark, but Sbyslava knew the King of the Germans was a powerful man. The Romans were strong, but why would someone pick a needless fight? Maybe there was something else going on? Maybe his last Empress simply died? Sbyslava nodded to herself—that had to be it. The simplest solution was often the best, she’d decided.

So she couldn’t seduce him—not that she had much experience at seduction anyways. One of her handmaidens had made quick work of a few guardsmen, but Sbyslava knew an Emperor would have far different tastes and needs than a guardsman looking to rut in a stairwell. Especially an Emperor who’d lost someone he loved long ago. Her eyes narrowed as the boisterous harbor swelled into view. All along the shore were an array of shining armor and massive plumes—if her mind hadn’t been focused, she’d have had to blink yet again at the sight.

Yes, in the midst of that panopoly, she saw him. Only the Emperor of the Romans would be clad in such resplendent robes, a crown of gold circling his brow with pearls hanging from the sides. He wasn’t as plump as she’d heard—not thin, but not fat. However, his hand rested discreetly on an ivory tipped cane. She couldn’t fully see his face, but she couldn’t help imagining he was frowning sternly at her.

No, words would not be sufficient, not by themselves.

Sbyslava smiled, a big broad array of teeth that complimented her well. She knew he could see her. Gingerly, she reached down, towards the lyra sitting on the ship’s deck. It was a clumsy looking instrument to her, nothing like the flute she knew from home. She would learn it—and anything else she could that’d please her future husband. It would be the best way to safeguard herself, her future children, and her family far away.

“It’s called the Oak and the Dove,” her father reminded carefully. “His favorite…”

“I’m not a fool, papa,” she smiled nervously. Her mind ran over the plan yet again. She would walk off the ship, playing the song she’d practiced for no less than six weeks constantly. Then, she’d bow, and say she hoped it pleased him, and offer him condolences. She would then say she would do whatever he required, and be his true and loyal servant…

…she hoped it’d work.

“I am simply reminding you, for my sake,” Mstislav said with a gruff grin, before wrapping an arm around her shoulder. “You’ll do well, Sbyslava! You’ll make us proud!”

“I will, papa,” she affirmed, her hands gingerly touching the strings.

==========*=========

June 23rd, 1286

Outside Sisak, Theme of Croatia

Makarios Ioannopoulos reined up his horse next to the small copse of officers and nobles, and stared out at the field ahead of them. In the distance, a sea of horses, men, banners and spears swaying on the march or rocking with a horses’ walk—all danced lazily in the hazy early morning sunshine. Hesso had come, with the full might of his empire behind him.

“Exciting day ahead,” Makarios said grimly, casting a glance to his left. There, Basilieus Alexandros II of Persia sat sternly on his own charger—a mouse of a man on a giant animal. A mouse with a deadly bite, the Germans would soon find out.

“Probably,” the King responded. Before battle, Alexandros was cherubic, laughing, giggling, excited about the danger to come. But now, just on the eve of battle, he was all business—stern, focused, eyes never wavering from watching his opponent’s slow deployment with the gaze of a hawk. There would be plenty of excitement to come.

Makarios urged his horse forward, till he was next to his Lord—excitement was not his forte. He preferred operations that went smoothly, plans that unfolded with no problems—no unexpected surprises, no daring against long odds. He’d had plenty of that during the attempts to get the army to the Balkans.

The Persian force first marched into Syria, intent on making its way by land across the Empire proper. However, when Prince Simon Komnenoedessa with the Basilieus and his commanders near Nisbis, he told Alexandros that his cousin Andronikos had made no provisions whatsoever for the Persian army to gain food during its journey. Edessa had been in the Persians debt—after all, it was Alexandros who drove the Aionite threat away from the Near East before it could spread to Syria proper.

Instead, the Komnenoedessas and their even richer neighbors the Chrysokomnenoi lumped together funds (coupled with a few loans from merchant guilds keen to keep the Mediterranean a peaceful Roman lake) to ferry the King and all 18,000 of his Persians across the waters, and safely to Ragusa. By luck, neither storm nor tide struck the Persians down, and the backbone of the army arrived safely in Ragusa during the first weeks of May, 1286.

“They’re coming straight this way,” Makarios grunted, squinting in the sunlight. He couldn’t see how many banners there were—save that there were many. The Spahbod looked behind himself for reassurance. The four vashti lay behind the hill, with the bloody Balkan thematakoi, the only remaining parts of the former Haemutikon left behind, were arrayed on the hill’s crest.

Makarios snorted. Everyone plainly knew it wasn’t the Danes that made Andronikos pull the two professional tagmata from the Haemutikon at the last minute—it was politics. Andronikos wanted them to fail. The Imperial grain monitors in Croatia proper were as useful as toads—and the peasants weren’t keen to surrender their food to Alexandros’ men. The local dynatoi helped some—the Princes of Serbia, and the Imperial City of Ragusa donated some money to the expedition, but not as much as hoped. An unexpected boon came from the rich Prince of Istria—Gottfried von Franken’s coffers were deep, and his generosity unexpectedly large. Everyone assumed it was because of his surname—Hesso Arpad, should he gain the lands of a von Franken, would surely confiscate them in order to ruin the closest dynasty rival to the German throne.

Yet the more Makarios spent time with the man, the more he was convinced that Gottfried von Franken was motivated more by opportunism than anything else. The man loathed Emperor Andronikos, and continually placed ideas before the council of war that should the Germans be defeated, the army should march north and begin despoiling the German countryside. Regardless of his motives, his deep coffers and filled granaries helped to alleviate some of the problems of fodder for the enlarged Haemutikon Stratos.

But food was only the start of the problems—so was the quality and number of men. Alexandros’ small core had been augmented by “tagmata” from no less than five themes and the Imperial City of Ragusa. On paper, it was a princely force—some 25,000 or so added to Alexandros’ rolls. All those soldiers had to be fed somehow, however, and more importantly, some of them were more hungry mouths than veteran soldiers.

The Croat contingent had been useless—Mother Church kept only enough men on retainer to stop bandits and other ne’er-do-wells, but no more. Neither did the Church have any decent contact with sellswords to fill the gap. The Serbs and Epieroites at least were usable as light infantry in a pinch. In fact, only the Ragusan detachment of mercenaries and the Istrian thematakoi showed up equipped like a proper army—three tagmata strong in total, enough to be useful.

“Looks like all of Hesso’s bloody cavalry,” Prince von Franken hissed. The man looked awkward on the saddle—he leaned towards the rotund side, his finely kept beard no doubt hiding a double chin. Yet his armor was finely made with black enameling with gilt trim. Only the Basilieus’ own white enameled masterpiece, complete with a shield bearing the double-headed lion of Persia, could outmatch the Prince of Istria in the morning light.

“That’s all of them,” Marzban Shirazi nodded grimly.

There was plenty of reason to be grim—the Haemutikon was low on food, low on money, and facing a force thrice its size. There was only one silver lining in this sea of darkness.

The Germans wanted battle as quickly as possible too.

Hesso had lumbered across Hungary with both of his armies, every man he could spare. The host was huger than Alexandros had been told—Shirazi’s scouts guessed there were as many as 30,000 cavalry alone, including some 10,000 mounted knights. Each man in shining mail dragged along with him peasants and retainers. Makarios had no doubt the final host was easily greater than 80,000—even more once the Poles joined the horde.

Yes, the Haemutikon Stratos had some 30,000 mouths to feed, but the Germans had twice as many, and pillaging the countryside only got one so far when the army was that vast. Hesso and his men had planned to ship food down the Ister using barges—a fine idea, straight from a Roman textbook—but Makarios’ Persian light horse three weeks before had raided north, crossed the Ister near Sirmion, and captured a number of the barges. The ones he and his men couldn’t board and float to the other side of the river, they burned. There was no telling how many of Hesso’s food ships they’d stolen or destroyed, but it’d certainly eased their own suffering.

The effect on the previously plodding German force was equally apparent. The Germans hastily threw pontoon bridges across the river to the west of Sirmion, then plodded across with all the speed of a stumbling elephant. Makarios smirked, watching as the horde pressed forward. Hesso’s barons were undoubtedly angry and embarrassed at the raid, and the kerns would be crying hunger and wanting to go home. The German King had only a few weeks to force a victory, and the sand was passing through the glass. The Germans lumbered forward, their attempts at speed conflicting with their size. The end result was a confusing mess, ponderously moving through the countryside.

Shirazi had only worsened the German’s predicament—Alexandros concentrated the thematakoi from the Princes on him, but spread out his own professional troops, with posts set up for riders to bring messages back and forth. It helped him ration out what fodder he could. While Makarios’ men raided barges, Shirazi and his horsemen crossed the Danube, sniping at the German’s sides, moving just slow enough the lumbering horde could follow, but just out of reach.

“It’s like leading a puppy along,” the King smirked, watching the oncoming mass of men, animals, wagons and dust. Makarios had to agree. The lands immediately along the river had once belonged to the Church, but the Metropolitan overseeing the region left its defense in the care of none other than Gottfried of Istria. The Prince had no compunction about ruthlessly ordering all the villages within five miles of German scouts cleared, the cattle slaughtered, the crops burnt.

It wasn’t his land, after all.

As the huge German and Polish army stumbled onwards, it had only one place it could go—Sistak, site of the major granaries in the province, a town built around the food storehouses that supported the peacetime Haemutikon. The Germans, tired, angry, hungry and looking over their shoulders to home as much as they looked forward, clamored forward. The peasants, the backbone of any siege, had to be going hungry—Istria’s men had cleared the surrounded land well, Shirazi’s riders nipped at the flanks. Five days before Alexandros sent his riders out, ensuring the last of his dispersed men arrived the night before. Now, the Persians and the thematakoi stood in the morning sun, already arrayed for battle as their enemies stumbled forward in a long, strung out mass.

The head of that enormous snake glittered in the morning sunlight before them—the core of the German and Polish cavalry, including Hesso’s ten thousand knights. Makarios knew the numbers—Shirazi’s scouts guessed there were 30,000 horsemen altogether in the leading contingent of the mob. These were the best fed, best armed, and best led of the German horde—they were the power, the heart of the motley army.

Bugle calls echoed distantly over the hills of Croatia. Slowly, the vast German horse deployed as best it could in the rather narrow fields. As he watched, the Spahbod nodded. Hesso’s plan of battle was obvious—he was launching a headlong attack. Shirazi’s men were right—the Germans were beyond hungry. They were ravenous, and Hesso could not lay siege to any castles, let alone the likes of Zadar or Ragusa, without his levies…

“They’re a mess…” Makarios said to no one in particular. Von Franken had helpfully provided a great deal of information on the banners used by the armies they would be facing—from the white and red eagles, it looked like the Poles were being shunted to the left. Some of their men were adamantly riding to the center, even as a yellow banner with a red lion on it pushed back. Makarios frowned, trying to wrap his mind around the German name. Habspurg?

“An utter disgrace,” Alexandros hissed, squinting. For a second, Makarios saw something familiar in the Emperor’s eyes—calculation, thought, the same look he’d seen countless times in the hills of the Zagros, the deserts of northern Arabia, or the marshes of Mesopotamia. Calculation, conclusion…

“Orders!” Alexandros barked. “Shirazi, Reza, Georgios!” he called cavalry leader to him—all his Persian officers, as well as the chief of Istria’s cavalrymen. The commanders trotted closer, as Alexandros finally nodded to Makarios as well. Ioannopoulos cast a longing look back at the well-prepared ambush behind them—he knew what was coming.

“Subtlety, Majesty!” he called, before the Emperor could even speak.

“No subtlety necessary!” Alexandros countered sharply. “Their deployment is a mess, their cavalry have no support! Once the nobles are routed off, the foot rabble behind will flee, and we’ll run them down!” The King turned to the Princes and Shirazi. “We’ll kick the head of the snake and kill the whole thing! Hesso won’t expect that! Look at that mess!”

Makarios looked up again—the entire mass had stopped, and a frantic array of bugle calls echoed back and forth. He swallowed—they were confused. If they arrayed that host, things could turn bad. If that host kept coming, disordered as it was…

“Shirazi, take your horsemen, and ride at them hard,” Alexandros was saying. “Shower them with arrows, insult them, whatever you must, but make them charge before they get ordered. Understood?”

“Yes Great King.”

“Go,” Alexandros waved. As Shirazi turned, whistled for his men and began calling orders, the Emperor went on for the rest. “The rest of you, form your cavalry on me, and send the light foot to the rear—flanks of infantry we already have waiting. Should we not break them, we’ll rally behind the foot, yes?” The Basilieus cast a look at Makarios, and a thin, stressed smile briefly crossed his lips. “Rest easy, I haven’t completely gone insane, Spahbod.”

“Thank you, Majesty,” Makarios nodded. The Alexandros II that Ioannopoulos knew had four basic strategems that were constantly reused, tweaked for this circumstance or that.

Charge it and kill it.

If the enemy was too strong to charge directly, use speed to wear them out—then charge them and kill them.

If the enemy was spread out, charge their detachments and kill them, if he was concentrated charge him headlong and kill all of them. Above all—charge them and kill them.

It’d worked before—calculated aggression that the enemy didn’t expect. Confusion, surprise, and disorder among the enemy were worth 10,000 cavalry.

Makarios began yelling orders to his men, and the Anusiya trotted from its former place of hiding up to the front in a formation that would have done a parade ground proud. Ioannopoulos smiled when swore he heard von Franken make a disparaging remark that the Basilikon in Konstantinopolis never looked so good. In the ten minutes the Spahbod’s men needed to deploy, Shirazi’s had ridden forth on their mission. When Makarios looked up finally, shield at his side, the mass of Persian light horse was already thundering back—an enormous pall of dust behind them.

The Germans were coming.

Makarios forced himself to remain motionless, steady as the light horse galloped through their lines. The Spahbod kept his mind busy eyeing the distance—he hoped the Basilieus would wait until the Germans were only two hundred yards off before ordering his…

“Anasuyi vashti!” Alexandros bellowed, hand finishing the clasp on that lavender cloak, “Ala El-Sayif wal Hurba!” The King spun his horse around, and before Makarios could shout a warning, the Basilieus barked to the Istrians in Greek the same command.

“Kataphraktoi, ready kontos!”

Metal scraped, and the diminutive Lord of Persia drew his father’s blade. Steel shimmered in the morning light as Alexandros started to trot, then canter down the length of the cavalry line..

“Majesty, shouldn’t we...” Makarios started to yell…

“Charge line! Charge!”

And then Alexandros wheeled his horse and was gone, purple cape flapping in the wind, his sword aloft as he galloped headlong towards the throng ahead. Makarios looked to the left, then the right—the marzbans and strategoi sat blinking, stunned. The men gaped as their King galloped on, alone. For a moment, Makarios was with them in stunned silence, before training and previous experience finally kicked in. A second later, his own sword was out.

“Protect the King!” Makarios screamed, spurring his horse. The motley host behind him echoed the call, and the so-called Haemutikon Stratos charged headlong into legend.

May 19th, 1287

Outside Orleans, France

“It’s only a scratch!”

It’d taken Prince Nikephoros a full three weeks after his arrival in Spain to find his ‘battle voice’—the bellow that could be heard above the clash of arms, the call that would steady men’s hearts. Pandomestikos Godwinson’s was like a thunderstorm, huge and menacing. Nikephoros knew his was different—reassuring, encouraging, not raging furious. Yet despite that voice, he bumped and jostled as the litter carrying him trundled onward through the disheveled morass of a battlefield.

France was not supposed to be this way.

For years, the Western armies had existed, been trained, for one purpose and one purpose only—to fight the French. The first part of 1286 had gone smoothly—Godwinson split his force into three taxarches, and an early spring thaw meant his men were over the Pyrenees by April. As the knights of France were marshalling in May, Godwinson was actually adding the feudal levies of Aquitaine and Toulouse to his own forces. The Romans were in position, ready, and the French had no idea what awaited them.

“I said put me down!” Nikephoros yelled again. He tried to raise his left hand to feel the side of his back where the arrow had struck, and he cursed as it moved sluggishly. Not now, not now! Nikephoros blinked, then tried to turn to look back at where he’d come from. In the distance, he could hear drums and horns, but he couldn’t turn around enough to see. One of his litterbearers slipped in the mud—the Prince felt a lurch, and heard an Occitan curse.

It was the mud that did them in. The first three weeks of June were filled with constant rain—buckets and buckets that fell from the sky in an endless torrent. The rivers swelled, and the roads began mudpits. The wagons of the Stratoi couldn’t move—and so the entire Roman war machine ground to a halt, just days before it was to launch its northern march, starting perhaps the largest ambush in history. Instead of catching the French unawares as Godwinson had hoped, it was the French, by some miracle, luck or perverseness of fate, that managed to hobble out of the mud first.

First blood was taken outside of Limonges—Nikephoros’ bandarches came upon a French detachment besieging several local castles. The fight was ugly and short, and the French did surprisingly well, holding their lines until nightfall and extracting a steep price from the Roman men, especially the thematakoi. It was the first time the Romans ran into a group of gendarmes, and it wouldn’t be the last.

Finally the litter crossed some unbidden threshold into the disheveled Roman camp. Nikephoros could see tents, pennants from the corners of his eyes, and he heard voices, shouts, calls. They were jubilant. Nearby, a trumpeter repeated some distant call—three short blasts.

Pursuit.

“We won?” Nikephoros tried to sit up. Once again, the silent, unbidden weight made his left side hang lower. He struggled with it for a moment, before craning his neck, trying to see above the cheering soldiers and the raised swords about him. A chorus of calls greeted his question. Bragging and congratulations filled the air.

The French were running finally.

As Nikephoros unwillingly made his way back to the churigeons, he pieced together what’d happened since his desperate, pell mell attempt to blunt the French threat. After a French arrow took him down, his horsemen evidently had smashed through the French flank, directly behind those stubborn gendarmeries that had broken thematakoi and line tagmata alike. While the French levies broke and ran, those three units coldly held their place, covering the French retreat. On another day, the Romans would have tried hard to crack them—but Godwinson’s victory had come at a high price.

Pandomestikos Godwinson himself had been wounded—he’d been in the front, as was his way. No one could tell Nikephoros where the old man was or his health, only that he’d been cut off momentarily and surrounded, only to hack his way back to friendly lines. They said his axe had been covered with French blood—and on the morrow, the armies swords would do the same. The French would break, the brave men promised. They must on the morrow.

But Nikephoros knew there’d be no tomorrow. Just like outside Limonges, the skirmishes around Poitiers, and the previous big battle near Gueret, the French would pull those precious men out during the night at the latest, and in the morning those men would be the rearguard as King Hugues and his nobles rounded up their scattered men. The French army battered, it was bloodied, but it was not destroyed.

The exact same as its Roman counterpart.

Instead of a quick and crushing victory, there was a slow, bloody waltz to the north. Godwinson’s columns would pursue, only to come across the French reformed elsewhere, stubbornly fighting, extracting another butcher’s bill. For 18 months it’d gone on, through the mild winter and into this spring. Nikephoros was jealous of his cousin to the east—as dispatches came from Alexandros reporting first Pest taken, then Praha, Nikephoros had been forced to say his men had tangled with another French force indecisively, or that this small town or that castle had finally been taken. To add insult to the injury, of course the dynatoi of Greece, once so reluctant to deploy their thematakoi, were now stumbling over themselves to send men north, for loot, if nothing else.

Finally the Prince saw the roof of a tent over his head. He didn’t need to smell the foul stench or hear the moans of the wounded to know where he was.

“Put him on the table,” the man gruffly ordered. Nikephoros felt a brief stab of pain as the littermen set him down as gently as possible. Just as quick as it came, it faded to something else—something dull. The Prince saw the churigeon’s shadow, and heard him grunting and muttering as the littermen shuffled away to fetch more wounded.

“It’s only a scratch!” Nikephoros loudly protested one more. He knew an arrow had hit him—he’d felt the sudden slap on his side. He knew he was bleeding. But for the love of God he didn’t want the churigeons seeing it! That side had always been a little numb, but now…

The dull ache was starting again. The Prince tried to sit up, but the churigeon’s hand clamped down. He laid back, all manner of curses coming into his mind.

“It’s not a scratch, Highness, ‘tis an arrowhead in your side!” the chirugeon hissed. “Now, lie back down and let me examine it!”

Nikephoros sighed, and did as he was asked. He felt poking and prodding—somewhat distantly. Sweat was pouring off his brow. Someone undid the clasps that held his mail over his side. Linen and cotton ripped.

“My God….”

“What?” the Prince looked over, trying his best to look naturally confused, even though he knew it was too late.

“Oh… it’s…it’s… this rash…”

Nikephoros nodded slowly, paling. He’d first noticed the thing at the start of the campaign—a white patch on his skin that felt strangely numb. He’d had them before—he noticed the first two years earlier—and he’d taken great pains to keep them hidden. Nikephoros had a voracious appetite for scrolls and books, and he feared not just what the churigeons would say it was, but what the results could be…

“What rash?” the Prince tried to sit up. He halfway slumped in the effort, but he pushed himself up far enough to stare the churigeon in the face. The man’s eyes were wide, as he stared down at the light patch of skin next to the bloody barbs of the arrowhead sticking cruelly out of his flesh. In another circumstance, Nikephoros would have smiled—Godwinson had said his chain shirt was finely made. It and the cotton gambeson underneath had taken most of the hit. The arrow wasn’t in very deep at all, but the wound was still bleeding all over the table.

But here, now, with his secret on display, there was no time for a grin. Not when his succession was on the line!

“H…Highness?” the churigeon asked quickly.

“You see no rash, doctor,” Nikephoros hissed, coldly spelling it out for the man. He glared at the man’s assistants. “Neither do any of you. Get the arrowhead out. I need no alcohol, nor a cloth to bite.”

Several of the assistants paled.

“But Highness…”

“You will say I have a high tolerance for pain, is that understood!” Nikephoros hissed. “Now get that thing out of me!”

==========*==========

Another long one! Alexandros as expected beats the Germans to a pulp, while in the West, Roman fortunes are not as ascendant. Alexandros’ success means he, as well as numerous dynatoi from the Balkans, are stuffing their pockets with loot from Pest to Vienna—undoubtedly a threat to Konstantinopolis. How will Andronikos respond to this turn of events? What is Nikephoros’ mysterious ailment, and will it remain a secret? What’s next for the Victors of Sistak? More to come, when Rome AARisen continues!

Last edited: