Kirsch27 - There's been several academic arguments as to whether the medieval mind could truly understand atheism the same way the modern mind understands the concept, considering how religiously saturated the medieval world was. Heresy and apostasy definitely could be possible--but that whole academic debate is outside the realms of the story.

RGB

RGB - Other than liking men, Alexandros and Nikolaios are about as different as night and day. Nikolaios wasn't nearly as flamboyant, or as self-confident...

FlyingDutchie - The former result from Andronikos the insecure boy coming to the fore might or might not be bad for Romanion. Given Ioannis' preference for wanton destruction and violence, the latter would be disastrous...

Carlstadt Boy - Not as of yet, mostly because the Imperial Navy really doesn't have any full scale enemies that can match it. Later on several commands are set up with local

themes fully dedicated to supporting the fleet, but there's not the same formal setup as with the

tagmata. There are great fleets, (

stoloi), but they're parceled out on an as-needed basis usually.

And without further ado, the enxt update!

“Getting all the rats onto the leaking ship is the best way to have a rat-free fleet.” – Andronikos Komnenos

April 15th, 1272

Isfahan, Persia

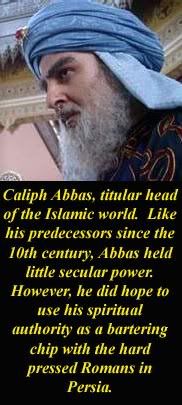

“His Most Excellent Lord, Abbas al-Mansur, Caliph of Islam, Commander of the Faithful!”

Alexandros the Younger, Prince of Persia, ruffled the purple cape over his shoulders and straightened the sleeves of his silken doublet. A seventeen year old semi-nervous eye flashed over to the other man in the audience room of the Isfahan Palace. Nikephoros Komnenos, Junior Emperor of Persia, stood stolidly next to his nephew, his purple robes rumpled an occasional speck of dust catching Alexandros’ eye. It was seldom that Nikephoros wore the full robes of state, and it showed.

Neither was it often that the Caliph visited the palace—nor was it often that the spiritual leader of all Islam sent hints to the Roman court his position against the Romans was loosening, in light of events to the north…

The chamberlain banged his staff on the tile floors once more, and fanfare echoed from trumpeters just outside the audience chamber. The man that swept into the room had a blue turban with a ruby medallion at its front. His blue and gold embroidered robes swished as he crossed the floor at a slow, stately walk, the dim light in the room glittering off the rings that glittered on his fingertips. The gray beard that flanked his face only increased his regal bearing.

“Greetings, Lord Abbas,” Alexandros bowed, as per protocol. He was a Prince, and thus below Abbas’ station. He watched as the Caliph looked at Nikephoros expectantly, and in vain—Nikephoros bowed before no one. An awkward silence ensued for a minute, before Alexandros hurriedly gestured towards the empty divan before them. Abbas nodded in thanks, then reclined back, casting glances over at Nikephoros—Alexandros wasn’t sure if they were looks of anger, or simple confusion.

“Greetings, Highness,” the Caliph finally said in perfect Greek, pointedly saying nothing to Nikephoros. Alexandros frowned—this were already turning sour.

“I trust you have found your apartments for you stay to be comfortable?” Nikephoros finally spoke.

“Indeed. Your Majesty is most kind,” Abbas nodded his head politely, and Nikephoros slowly did the same. A small smile crossed the Caliph’s face—he was mildly pleased. If only he knew, Alexandros wondered, how much Roman protocol Nikephoros had just broken by even bowing his head slightly.

“Let us be to business then?” the ever martial Nikephoros said, snapping his fingers. Servants materialized, setting a plate of fruit between the three lords. “The Mongols invade,” Nikephoros continued as the servants went about their business, “and we want to end the misfortunate misunderstanding between us.”

“Misunderstanding?” the Caliph raised an eyebrow. He looked about for a moment, mildly confused—clearly he wasn’t used to someone simply bullying to the subject at hand. “There was little misunderstanding, Majesty. Even if half the tales are wrong, your lord father spat on my kindly letter, cursed my name and told me to stay outside your realm forever! One can hardly misunderstand such words or actions…”

“My lord grandfather took you to mean you wanted him to kneel before you,” Alexandros said quickly. “Would no king act in the same way if another demanded him to abase himself before them? Would you not respond in that way?”

“I said no such thing,” the Caliph raised his face angrily. “I merely asked for my rightful possessions to be restored in Baghdad, and that I be allowed to resume my title as the Commander of the Faithful! I even have a copy of the letter I sent to

prove my intent!”

“You deny you sent this?” Alexandros asked—the Komnenoi too, came prepared for the discussion. The Caliph curtly took the document, and briefly scanned it. After a moment, he harrumphed.

“Yes, I categorically deny it,” the Caliph said with quiet anger. He tossed the letter aside. “It is rubbish, and full of needless insults. The Commander of the Faithful would never debase himself to write something so… crude.”

“Perhaps we all have been deceived?” Alexandros said quietly. His cousin in Konstantinopolis was clever—would he be so callous as to sow discord on the eve of a Mongol invasion, just to rid himself of Alexandros’ grandfather?

“Lord Abbas, would you be inclined to support the Roman state in Persia against the Mongol?” Nikephoros asked bluntly. Alexandros sighed—he was sure his father would’ve put things more delicately, but Nikephoros’ face was the better known. Besides, Alexandros the Elder was still in Baghdad, marshalling the Persian armies in Mesopotamia along with grandfather Gabriel. Nikephoros was here, in Isfahan, and the leader of the most powerful Persian army in the field. His few words carried much weight.

“Should I, after the insult I was dealt?” Abbas crossed his arms even as he smiled pleasantly at his triumph moments before. “Would your father, or you, when a great army of believers is crossing the land?”

Alexandros frowned—surely the Caliph knew of Rayy? What was he up to?

“Does Arghun march truly on Persia with an Army of Islam, intent on restoring the faith?” Alexandros heard his uncle grumble. Nikephoros shifted uneasily on his chair—the movement made the Prince think of a grumpy bear. “At last report, he’d looted the churches

and mosques of Rayy, putting the members of the

ulema in chains.”

“But as a Muslim, he must respect the wishes and will of God’s appointed ruler of the

Ummah…” the Caliph continued, the smile on his face seeming more fixed by the second.

“As much as the Turk respected your ancestors?” Nikephoros said dryly. “Or those that came before the Turk?”

“But he comes with a vast host, as numerous as the sand on the shore,” the Caliph rejoined. “Your family squabbles are infamous, Majesty, and your realm is split by divisions and rebellion. Why should I expect you to stand? Why should I not come to an arrangement with Arghun? Your army is strong,” his smile thinned, “but battle is a wily mistress. Strange things happen within her arms.”

“As strange as men bearing a strange mark on their forehead savaging all the mosques of a city?” Alexandros asked directly—Abbas was stalling, stalling for concessions. He knew the Komnenoi needed him, and he wanted as much as he could get. Fair enough, the Prince reasoned. Two could play at that game.

The Caliph blinked. Only four of the

mullahs of Rayy had managed to escape. True, Nikephoros’ spies had confirmed that several high ranking Mongols had managed to stop the looting, but the Persian Komnenids planned to keep that information as close to their bosoms as possible.

“I… have heard of that. Surely it was a mistake?” the Caliph asked guardedly. By his tone, he sensed the countertrap being drawn around him.

“We can produce some of your clergy who would disagree,” Nikephoros said gruffly.

“Can we be so sure?” the Caliph began say in that quiet, calm voice. He wasn’t about to be ruffled, even as the Komnenoi threatened to reveal him as a supporter of someone who had burned mosques and slain

imams.

“So you should ally with him, despite his attacks on Muslims?” Alexandros raised an eyebrow. He folded his hands, and leaned forward. “Excellency, let’s assume for a moment that my uncle, a respected commander who has defeated the Mongols handily before, is defeated in the field. What

would happen, Excellency?” Alexandros asked. The prince glanced over at his uncle—Nikephoros raised an eyebrow, but said nothing. “Do you think the Romans in the west would stomach a Mongol Empire on their eastern border?” he heard his voice rising. “The fact that we sit in this very hall is a sign of how much they would

loathe such a prospect! They would

abhor the very idea!”

“But your cousin, Andronikos,” the Caliph kept that damned smile on his face, “does not

like your grandfather, or your family, for that matter. Why,” the Abbasid heir leaned back on his divan, “should he lift a finger in your defense? The Mongol cannot hold this area, the border would not last long. Why not let the Mongol break you for him?”

“You know little of the Romans, sir,” Alexandros growled. “Even if Andronikos did not want to move, the

army would want to move, and my cousin is as much a slave to his generals as they are his servants!” He paused, trying to collect his thoughts—a second later, he thought of what he needed to say. “Excellency,” he leaned forward, “I ask you this—what would the Mongols do, or even

you do, if the full weight of the Romans, from Spain to Egypt to Italy to Anatolia, were to come hurtling this way? And what would happen to the Muslims of the Neat East? There would be war, rebellions and chaos on all fronts, but my cousin need only raise the banner of holy war, and Muslim culture all around the Mediterranean would be ground to dust!”

“And your

empire would be ground to dust as well!” the Caliph snapped. “Who pays much of your taxes?

Muslims. Who rides in your armies?

Muslims. Who make up half the lifeblood of your Roman world?” He leaned close. “

Muslims. Without us, your empire…” he frowned, shrugging.

“…would be nothing?” Nikephoros muttered darkly.

The verbal tripwire jerked. The final trap was sprung.

“Yes, it would,” Alexandros nodded, jumping into the gap. “That is why my uncle and I have a different proposal, a different trajectory our histories can take. On that does not lead to mutual destruction and death, but to cooperation and alliance.”

“Oh? You and your uncle?” the Caliph asked. While the words were respectful, the tone was dismissive.

You? A seventeen year old boy designing policy for me, the leader of the Ummah?

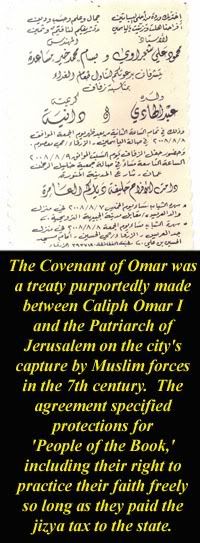

“Yes, namely a reverse of the

Al-'Uhda Al-'Umariyya,” Alexandros said, ignoring his tone.

The Caliph chuckled lightly. “A promise of religious freedom? For what? The

Al-‘Uhda promised the

dhimmi of the Caliphate they had to only pay the

jizya taxes, and they were forever absolved of military service!

Your armies are full of Muslims, faithful or otherwise!”

“We would go past the

Al-‘Uhda,” Alexandros said quickly. “We’d offer Your Excellency a return to Baghdad, and a position of great authority…”

“The

Khalifa relegated to being a puppet of an unbelieving lord?” Abbas shook his head. “No, young lord. I think the supreme spiritual head of Islam can do

much better.”

“You would have full legal control over any decisions of

shar’ia law,” Alexandros rejoined. “And the Emperor would consult with Your Excellency on all decisions that could impact the Muslim community.” Abbas’ smiled remained fixed, but Alexandros thought he saw a twitch at the corner of the man’s eye. Did he have him?

“I thought you Romans considered yourself the supreme legal authority?” the Caliph quickly asked, running a hand over his garments. Alexandros bit his tongue, trying to keep from smiling—yes, he had the man.

“We have no desire to interfere with

shar’ia law as it applies to Muslims,” Alexandros’ uncle clarified. “We have not interfered with it before, we shall not now. In the cases of Muslim versus non-Muslim, we shall divert affairs to a mixed court of both faiths.”

“I see,” Abbas said. “But the

Khalifa has traditionally been the greatest secular, as well as religious authority in Islam. Why should I…”

“Would you have a position of respect and influence, or be sitting in a camel’s tent, a fugitive from Mongol and Roman alike, your words cut off from the

Ummah by discord and war?” Nikephoros grumbled. Even while sitting without a frown, Alexandros’ uncle reminded the prince of some squat mountain, low, powerful, and all the more threatening because he

didn’t raise his voice.

The Caliph visibly swallowed.

“I… well,” Abbas said quietly, running those fingers over his silken robes nervously. “Such an…arrangement… would be beneficial to all. But surely…” a sudden, almost relieved look broke over his face, “the Emperor Gabriel would not approve of such an arrangement? His desire for

Konstantiyye is legendary. I doubt…”

“Grandfather is not the only one who rules here,” Alexandros nodded towards Nikephoros, “and you would find you have far closer friends in my father, my uncle, and myself, than you could ever find in my grandfather…”

“Konstantinopolis is lost to us,” Nikephoros nodded his head quietly. “Emperor Gabriel surely will realize that now,” he added, “If not, he’ll realize it shortly.” By the glower in his eyes, he made apparent he’d

force his father to understand.

“My grandfather has shown the people of your faith far more leniency than any other Christian prince,” Alexandros added, “and my father and uncle have granted even more tolerance and respect to your faith than my grandfather. Despite cries from the priests of our faith to do so, we have not closed mosques, and not forbade the preaching of Islam…”

“Indeed,” the Caliph looked down, face somber once more. For a moment, silence hung between those rich tapestries, until the Caliph looked up for a split second.

“Andronikos will come, with the full might of the empire,” Nikephoros growled. The Caliph bobbed his head, and looked down once more silence reigned. Just when it seemed impossible for the thunderous lack of noise to continue, the Caliph sighed, then looked up once more. Was the look on his face one of relief, or resignation?

“Arghun’s troops have attacked mosques, and the empire will come. I…” the Caliph looked between the royal pair, “think we should continue our negotiations in full.”

“Good,” Nikephoros slapped his hands on his lap, and quickly rose. “Alexandros and my

logothetes will continue the discussion.” The junior Emperor of Persia walked over towards the window to the palace, his hands sliding into one another behind his back. “I shall be leaving within the week with the army to face Arghun…”

“May

Allah protect you and your men,” the Caliph bowed his head, before looking at Alexandros, “and may He rightfully guide our future discussions…”

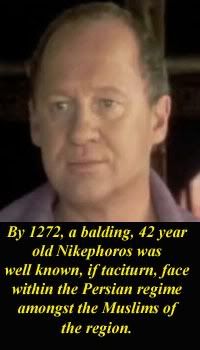

June 22nd, 1272

100 miles north of Isfahan

Nikephoros Komnenos thought back to that day in Isfahan, two months before—the hope, the future that it implied. The junior Emperor of Persia rubbed a hand over his jaw—the slash to his face stung, and fresh crimson stained gauntlets already brown from dried blood and sweat.

“Ah!” Nikephoros looked down—his boot had bumped some poor stricken fellow. The Emperor gingerly backed up—he didn’t want to cause another any more agony in their last moments. The Emperor looked towards David Donauri, called Koutsos, one of his aides, and nodded.

“Majesty?” Koutsos asked, voice shaking slightly. His eyes flecked around at the growing horde around the small group of men.

“Help him,” Nikephoros said. Koutsos walked over, and mercifully dispatched the dying soldier with a clean blow to the neck. There was no reason to prolong the man’s agony—not when their own would so shortly come to an end…

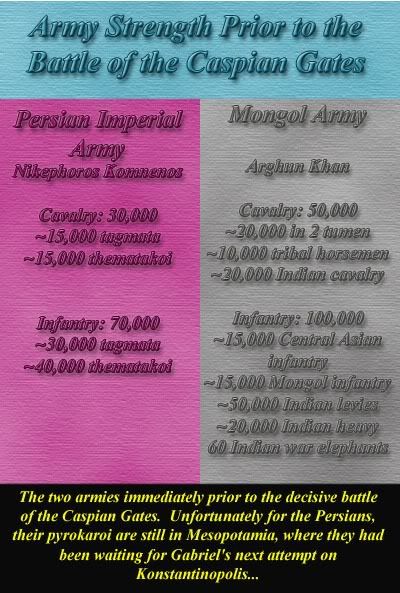

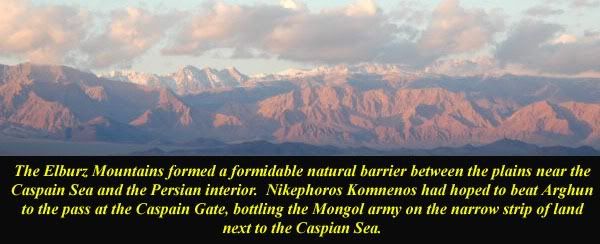

The campaign had began two months before with Arghun still north of the Elburz. Nikephoros’ plan was simple, making use of the Persian terrain to the hilt. His army, now marshaled and ready outside Isfahan, would drive north at full speed for the Elburz passes. The goal—hem Arghun’s huge army on the narrow coastal plain north of the mountains and wait. The Persians under Nikephoros’ command knew the mountains, and would have supplies streaming from the rest of the empire to their aid. Arghun would be hemmed in countryside his army would quickly strip bare, his only route of supply a narrow ribbon along the Caspian coast—easy fodder for raiders. The Mongol would have no choice but to force a way through the mountains, or quit his campaign. If the Mongols retreated back to their homeland, so much the better. If they sought battle, Nikephoros would face them in the midst of the Caspian Gates, where their numbers would be their downfall.

Nikephoros’ plan would have certainly worked if the Turkish Sultan had ridden to battle, but alas, news of the Caliph’s agreement to support the Persians was late in arriving in Zaranj—and was controversial. Many Turks had not heard the news of Rayy, and some who did refused to believe it. To them, Arghun was a promised Muslim conqueror, a hero who could restore the

Ummah to its former power and glory. When Sulieman finally

did move, it was sending his son Selim with 6,000 men, not the 20,000 Nikephoros had hoped for.

Even these men were too late for the campaign, however.

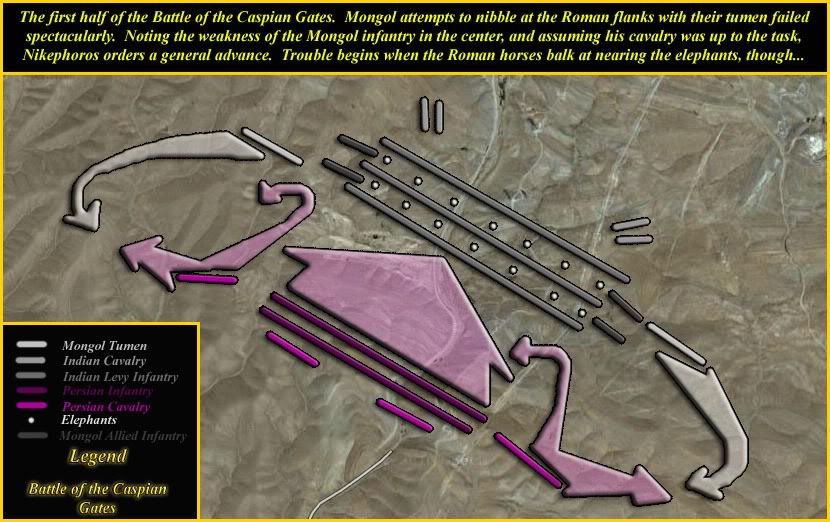

Arghun and his slow, ponderous army had stolen a surprise night march on Nikephoros’s force. Instead of the Elbruz, Nikephoros found the Mongols deployed for battle on the plains of Dasht-e-Kevir, just beyond the mountain foothills, and within sight of the passes Nikephoros sought to occupy. Caught in the open, Nikephoros knew he’d done his best—he’d found a patch of rocky ground he hoped would slow the Mongol horse, and arrayed his army on the defensive.

Arghun’s army was massive—and the weakness of all massive armies was time. A host that massive simply couldn’t stay in one place for long before stripping the ground bare. Nikephoros had dragged nearly half of the food reserves of Isfahan with his own enormous army to give it a few vital day’s edge. Arghun would have to attack him—the Mongol Khan would have no choice. He needed a decision.

Nikephoros’s tongue wiggled, tried to catch as much of the grit stuck in his mouth as possible, before the Emperor unceremoniously spat the mess onto the dusty ground. There were few around him left to watch this most unroyal act—not that there were many Romans left outside that little, bloodied knot to care anyways. Slowly, the emperor looked around him, eyes counting. He reached 150 enemies amongst the enemies in the first row before he lost count. He gave up—knowing the odds wouldn’t help matters anyways.

Things had looked far different that morning—as Nikephoros had expected, Arghun’s

tumen had flown to the wings, the tactic of the Mongols since the days of Nikephoros’ grandfather, and the most effective use of their awesome horsemen. Nikephoros’ horse had shadowed, but stayed close, and most importantly, stayed out of those broken rocks and rough ground. He dared the Mongols to close, to try to tangle with his flanks.

And close they did.

Oh, the

tumen had come, and oh, if only his father had seen how his once shy Persian levies had performed! They and the light infantry did wonders on that broken ground, keeping the

tumen away from the army’s flanks. Twice the devil horsemen had come too close, and twice they’d fled, bloodied and torn. Nikephoros thought he tasted blood, and so he’d given that fateful order—

”Skoutatoi will advance, at the double.”

To the eye, Arghun’s fatal weakness was his infantry, those levies that held the center of his army amidst the elephants. Nikephoros intended this to be the coup de grace—the elephants wouldn’t matter if the sea of levies in the center collapsed, and collapse they would if the

Gond,

Pistohetaratoi and the other Persian heavy cavalry hit them full bore, the

skoutatoi following up the advance

en masse. The spearmen opened ranks just as planned, the cavalry rumbled ahead, as planned, the Persian infantry close on the heels of the trotting horsemen. But for the impending siren call of victory and glory, Nikephoros had not known two things.

One, that his cavalry would not, could not, charge the Mongol elephants. The men were willing—their blood was up, they’d seen the vaunted

tumen stymied. The horses, on the other hand, were

not willing. The trumpeting beasts, trunks waving about, gleaming tusks glinting in the daylight, frightened the horses to a standstill. Nikephoros had cursed like a common trooper, screamed at his mount, dug his spurs in its flanks, but it shied, whinned, and circled, refusing to get any closer to the Indian monsters—and thus, Arghun’s infantry clustered amidst the sea of giants.

The Roman infantry stumbled into the backs of the Roman cavalry, and for one fatal moment, the Roman army became a jumbled mass as commands interwined, and frightened horses bucked and kicked at the hapless footmen who came near. In that moment, the second thing Nikephoros hadn’t expected roared out to surprise.

The

tumen hadn’t been all of Arghun’s cavalry, and the Mongols

Indian horses were used to fighting in and amongst the elephants.

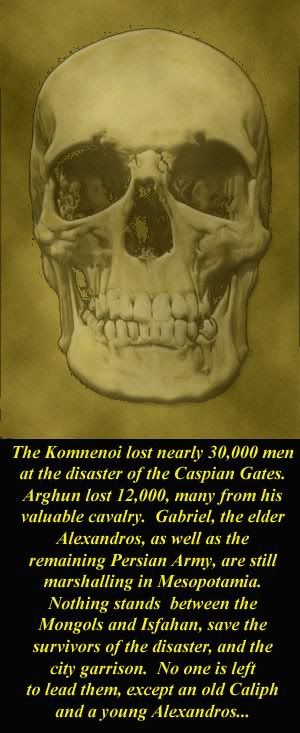

The image still sent a shiver down Nikephoros’ spine—the Roman infantry was disorganized, confused, when Arghun’s Indian cavalry thundered from around the elephants and headlong into the jumbled Roman ranks, closely followed by the huge beasts themselves. The was no time for the famous Roman spearline to form, no time for the archers to deliver their hail of whispering death, no time for the Roman cavalry to launch a spoiling attack. One second, the levy infantry was retreating back into that forest of behemoths, the next, thousands of cavalrymen were roaring into the Roman left and right flanks.

They caved.

It wasn’t a stubborn, dogged collapse—it was instantaneous. One moment, there were confused bodies of soldiers. The next, there were so many panicked men, running for their lives as lancers ran them down and elephants brayed and thundered in pursuit. As Nikephoros looked behind the small knot of men around him, he could still see the dust pall that lay behind—those damned cavalry were likely chasing his men all the way back to Isfahan!

Slowly, the Emperor looked back around, at the vast array of levy infantry before, beside, and behind him. These were the levies—the shield and spear conscripts from Arghun’s Indian lands. Someone coughed—Nikephoros caught a look at the son of the Prince of Hamadan. Ioannis Dadiani’s left eye was crusted over with blood from a sword slash to his face. His right eye was wide in terror as he propped himself up with his sword. The Emperor looked around—the rest of the

Gond—

his Gond—stared around blankly. Ahead, the mass of Indian soldiers shifted, then parted… a man bearing a dot on his forehead, clad in fine silks and a turban, galloped through. Another man that looked vaguely like a Mongol, followed. The pair rode forward, within shouting distance of the bloody copse of Romans.

“Nikephoros, son of Gabriel!” the Mongol barked.

Nikephoros sighed, stepped over his dying aide-de-camp, and in front of his men. He said nothing. The Indian and the Mongol stared at him both for a moment, before finally the Indian barked some words—harsh, alien.

“My master is

Raja Basavanna of Kalachuri, a vassal of Arghun Khan.”

Nikephoros said and did nothing. The strange Indian made was visibly annoyed that his nominal captive didn’t even bow—he snapped more angry words.

“My master offers you and your men a chance to surrender. An Emperor of the

Da’qin would be treated with the utmost courtesy, and my master would gain great honor.”

Nikephoros looked up for a moment, then levelly back at the two officers. Slowly, deliberately, he shook his head. There was only one place for a Roman emperor that was surrounded, defeated. A prisoner’s cage, no matter how gilded, was not it.

The tall man’s face grew thunderous, and he barked another slew of words—harsh, staccato noises that grated Nikephoros’ ears. The Mongol turned. “You truly refuse to surrender? You will most certainly die, my master says.”

Nikephoros looked up at the sky above—the dust was clearing, and he was surprised by how blue it was. No clouds in the sky, nothing to blemish what would’ve been a beautiful day. He sighed, looking back at the Mongol.

“I know,” he replied, in Turkic.

The man’s eyes went wide. He blinked uncertainly, then spoke to his master. The spotted man grunted something harsh, before reining his horse around.

“My master,” the Mongol said, “says he’ll give you and your men a minute to pray to your gods, before he sends you to them.” Without another word, the messenger joined his master, disappearing behind that mass of strange men and great beasts. From somewhere in the distance trumpets blew. The elephants bellowed, and the soldiers all around began a rhythmic, thunderous chant as they slowly closed that steel vice.

Nikephoros turned around, watching the horde closing in from all directions. The men were armed with light shields, little in the way of armor, and spears. If it were just them, Nikephoros’ men would be able to make quick work of the lot. But the elephants…

…so this was the end.

Nikephoros caught the distinct smell of urine in the air. He frowned…all around, his men stood, warily looking at the host that surrounded them on all sides. Some busily crossed themselves, others shivered like leaves in the wind.

Nikephoros, however, smiled.

Few men knew when they would die, or how, but these few—they would not only know, they would decide the fate of a few others before they left this world. If this was the end, there was no point to resisting—better to die and save the army and avoid capture, than live under the boot of a Mongol. Another roar washed over the detachment before them—elephants trumpted, trunks waving lazily in the air. Nikephoros looked to his left, then his right, and drew his sword one last time. As he calmly scraped steel against scabbard, it seemed the men around him steadied. Nikephoros the Calm, the Cool—he faced certain death without fear, without remorse.

“Majesty, what are your orders?” Koutsos asked, his voice steadier than before.

“Make them pay dearly,” Nikephoros said grimly, readying his shield to accept a charge.

So the Persians have suffered the single worst Roman defeat since Neapolis, with the last organized Persian army over the Zagros in Mesopotamia. Will Alexandros stand and fight, or will he try to march the survivors through the mountains to unite the last of the Persian armies (thereby ceding central Persia to the Mongols)? Will Arghun move quickly enough to make the 17 year old’s decision moot? And was Alexandros and Nikephoros’ initial assessment of the Main Empire—if Persia falls, it

will move—accurate, or is Andronikos that dedicated to the downfall of his greatest enemy? We go back to Konstantinopolis, next time on Rome AARisen!