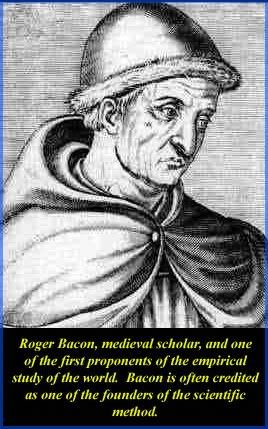

“His Majesty has a keen mind, full of questions and eager to learn. Unfortunately, he has inherited the stubborn streak common to his family and rank. When he has dug in his heels, few men can move him.” – Roger Bacon on his most famous pupil, Andronikos Komnenos.

November 3rd, 1259

Andronikos Komnenos gave an entirely unregal sigh, wishing for the fifth time today he’d decided to bring the falcons along for the hunt.

Instead, the 12 year old

Megas Komnenos had decided the temperamental birds weren’t worth the time. Not today. But with the hassle of setting traps and then checking them, the Emperor felt like cursing his own-short sightedness.

Hunting was normally a massive excursion at the Komnenid court—a chance for the great nobles to see each other and be seen, for negotiations and plots to take place far from the eyes of the city, for the imperial family to show its largesse, splendor and power. Yet those events annoyed the now 12 year old Emperor of the Romans to no end. There were many instances

in court, in the city, where the family’s power could be shown off—for Chrissakes, that was the

purpose of spending tens of thousands of gold pieces maintaining the palaces, the servants, the court itself! In the city, one could properly keep track of the plots, the counterplots, and not expose oneself to the risks of the hunt—Andronikos knew his history, and knew what happened to Emperor Manuel Komnenos in these very woods.

More importantly for the boy, hunting was a

joy—something that was soiled when hangers on, nobles, and their lackeys galloped around, scaring the game, and drinking their way to stupidity.

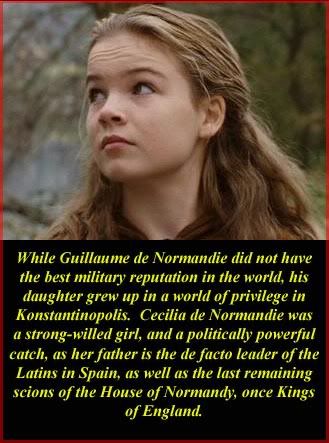

So Andronikos was out today with just a select few—Master Roger Bacon, his trusted tutor, his friends Cecilia de Normandie and Ioannis Angelos, and a minimal contingent of the

Rigal, no more. The woods was a refuge, a place where he could get away from Konstantinopolis and the mask the city forced over his young face. He needed this distraction, especially on this day. Both Cecilia and Ioannis were trying their best to keep him in good spirits—Cecilia by proving twice she could hit a target almost at the range Andronikos could, Ioannis by pranking two guardsmen and in general being his exuberant self. However, despite their years together, one man didn’t seem to care, or at least understand, why Andronikos was not in a good mood today.

“…and that is the reason for the difference between hawks and falcons,” Master Roger Bacon, Tutor to the Emperor, finished his long soliloquy.

Andronikos looked over at Cecilia and held back on the sigh he wanted to give. Master Bacon might have been from the Capetian Kingdom, but he’d attracted the attention of

Metropolitan Aquinas, and found a post at the palace school. From there, he’d impressed Emperor Nikephoros enough that the Frenchmen had been named personal tutor to Andronikos some three years before. Sharp-witting and charismatic, normally he held Andronikos’ rapt attention with his fascinating theories on the reasons why all sorts of plants and animals were molded differently by the hands of the Divine.

But not today.

“Take a look at that!” Bacon reached over as their horses lazily ambled along the trail. There was a crack from a nearby bramble, and the tutor held up a simple nut for his pupil’s observation.

Andronikos sighed. “It’s a pistachio.” It wasn’t that Andronikos didn’t find natural science interesting—it was

fascinating, like most things Roger Bacon discussed with his most important pupil—it was just that today, of all days, was one where Andronikos wanted to be alone.

It was the anniversary of his father’s death.

Even though he man had died without ever meeting Andronikos, the young man felt he

knew Alexios Komnenos. He certainly had heard enough stories of the man—his mother described him as kind and chivalrous, Nikephoros had described his brother-in-law as a lion on the battlefield. All in all, the glowing descriptions made the late King of Mesopotamia seem to be a shining knight on a hill, the epitome of all that was noble, righteous and good.

“Yes, it is,” his tutor said quietly, “but here, take a closer look.”

Andronikos sighed, and did as he was asked. Like he always did, like everyone told him, regardless of what he thought, or what he wanted to do.

Even this young, Andronikos knew that in some ways, the only ‘normal’ life for him was what he found through the lives of his friends. He’d gone on this minimal hunt to

get away from the courtiers, the flowering attention—all of it. He wanted to be

alone. It was only when he was alone, when he was away, that he could be himself. In the city, he had to sit rigidly, stoically, through meetings, ceremonies, and all manner of pretentiousness. To do otherwise was to invite gossip at best, and plotting at worst—both things the 12 year old knew from his step-father, mother, and history, to be

bad. Emperors had toppled from their thrones for less, and

child-emperors were especially vulnerable…

But beneath that exterior of grace and maturity

was a twelve year old, a boy that longed to play, that wanted to whine, laugh, and joke—things he couldn’t do in the stuffy confines of ceremony and court that was The City, especially as news of his uncle’s rapidly deteriorating condition filtered out of the Great Palace. Initially at the start of the year Emperor Nikephoros had rallied—he’d called for wine and food, sat up in his bed, and even took papers from Andronikos’ step-father. However, all that changed with the coming of summer’s heat. Corruption and pus had started seeping from his wounds soon after midyear, and a fever quickly followed—one which remained unbroken even now, four months later. The Emperor had gone from lucid if in pain to barely waking at eat simple gruel. Even Andronikos knew it wouldn’t be long.

Yet as the boy looked at the proffered pistachio, he found even this getaway soiled by the needs of state—in this case, his tutor trying to use the excursion as a way to further lessons in ‘natural science.’

“Look for the tiniest detail, Andronikos,” Bacon dropped the nut into the Emperor’s hand. “The answers to our questions are often right in front of our noses, if we cared to look close enough.”

“Bullshit,” Ioannis yawned, lazily looking over at Bacon. “You’re full of bullshit.”

“Ioannis Angelos!” the priest erupted, like he did

whenever Angelos let loose with his profoundly scandalous tongue.

“You said that honesty is the course of action for a noble, honorable man,” the son of the Prince of Ikonion said, voice high pitched and scratchy in mimicry of Bacon’s own. “I’m being honest! I think your little phrase is bullshit!”

Normally Andronikos would have snorted at his friend’s prickly comments—Ioannis was always good at using his cutting slash down the proud and vain. In some ways, Andronikos was jealous—where the young Emperor was forced to be quiet and respectful seemingly all the time, Ioannis, as a second son, was free to let loose with profanity, fight, and cause mayhem as he saw fit. Where Andronikos would bow politely, speak politely, and nod politely, Ioannis would spit at the foolish, curse at the vain, and tell anyone a dog was a dog, a horse was a horse—regardless of who the target of his tongue was, or their station.

“Do not sully my words with your dark logic!” Bacon snapped, bristling at his own words being flung back in his face. This too, on any other day, would have provoked laughter from Andronikos…

“Whatever,” Angelos waved his hand dismissively, “I’m going ahead to check the traps.” He spurred his horse slightly ahead, before staring at Andronikos with a mocking glare. “It all would’ve been simpler if

someone had agreed to take the falcons today…”

His voice dropped off at Andronikos’ lack of a response. For a second, the two friends looked at each other, before Angelos finished the unspoken conversation with a nod. He yanked his horse about, and galloped ahead.

“Foolish boy,” Bacon hissed, before returning his full attention to his star pupil. “So, Andronikos, what does that tell you?”

Andronikos looked at the pistachio again, cursing its existence in his mind. “Perhaps the hard outer shell is meant to protect the seed on the inside.” The boy frowned, only partly from concentrating at the problem Bacon had posed. “But then how would it grow? Is the outer shell open to water and dirt? If so,” his mind went on, facets of knowledge and logic focusing on the problem, and not his emotions, “it does not make a good defense, does it?”

“So we’ve arrived at a quandary,” the tutor smiled, “a natural science problem. Why did God, in his infinite wisdom, create the pistachio with the hard outer shell? If it was for defense, the shell is not impermeable, it can be breached. But if it is permeable, it is not a solid def…”

“Perhaps God meant for the shell to protect a few, discourage lazy squirrels and humans from opening the tougher shells,” Andronikos interrupted with a growl. In a second he could think of about twenty members of court who would’ve asked a servant to open the pistachio for them out of sloth. “The easier shells are left by Him for the nourishment of other creatures?” he added quietly.

“Aristotle would have been proud of that deduction,” Bacon beamed. “Remember, Majesty, there is no problem that can’t be solved by the brothers of reason and faith,” Bacon said.

“Yes, Father Bacon,” Andronikos said mechanically. The priest frowned, and Andronikos looked down.

“Do you not agree, Majesty?” Bacon asked.

“I…” Andronikos started to say, his mind wrestling between speaking the truth, or keeping decorum. Teaching shoved into hia mind since he could talk forced him towards the latter. “I wonder when Ioannis will return with the hares?” the boy said, forcing a smile onto his face. He looked over at Cecilia. “I’m starving!”

Her eyes were quiet, worried. Andronikos quickly looked down again. Those thoughts, those angry thoughts, started to well up again. Andronikos tamped out those flames, trying to keep the fire from escaping.

“Is everything alright, Majesty?” Bacon pressed. The flames welled up again in the boy’s mind, brighter and hotter than before. Bacon had been his teacher for five years—he knew Andronikos in and out, or at least, better than the other tutors.

The boy thought for a moment about telling the tutor to simply drop the subject, before deciding that would only make things worse—Roger Bacon practiced what he preached, and thought that all problems should be talked out, no matter how painful the subject matter. Andronikos wanted to tell him he was throwing dry logs on the embers in Andronikos’ mind. The boy settled on giving the priest a stare, a warning glance.

Drop the subject.

“Majesty, what is on your mind?” Bacon asked gently.

Finally, with a silent roar, Andronikos’ resolve snapped.

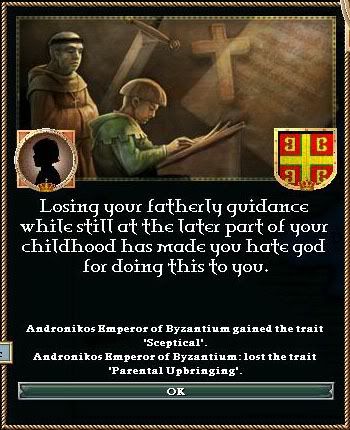

“That God as a piss-poor sense of humor,” Andronikos found himself growling, before his mind could catch his tongue.

“Andronikos?” Bacon blinked.

“I said God has a piss-poor sense of humor!” Andronikos heard himself say. He knew he was shouting now, but his voice sounded distant, far off, as if his mind was elsewhere while his mouth let loose with pent-up frustration and anger. “You speak of a Just God! What Just God kills the innocent and lets the guilty live long?”

The words hung in the air, a Sword of Damocles poised over Andronikos’ soul—and the boy didn’t care. There was relief, their was release, as soon as those words tumbled into the open. He felt his hands clench as he glared at the priest, the paragon of goodness and truth—lies, all of them!

“That’s a question that tries our faith,” Bacon said slowly, his voice still quiet, still damningly calm.

That infuriated Andronikos more! Bacon was addressing him like he was some wild animal that needed to be shushed! He wasn’t! He was hurt! He was angry! And he wanted to know

why.

“Sometimes God sees fit…”

“Well,

God saw fit to make sure my father died when I was a babe,” Andronikos interrupted, “and

God saw fit to create that beast of a horse that nearly killed my uncle!” the boy snapped. “

God saw fit to make my mother marry a man that makes her sad! I hate… I…” Angry words rushed to Andronikos’ mouth, but now, late but firm, his mind finally caught up. No more words came out of his mouth. Instead, he gritted his teeth, and glared off into the glade. No damn deer in sight, of course.

For a split second, Andronikos stood alone, the silence of the woods closing in around him. He knew his friends were staring—even Ioannis didn’t have the temerity to utter what Andronikos

almost said. But that long, agonizing moment was merely a moment. The next, he found a hand resting on each of his shoulders. The boy, angry at the world, looked left.

There was Cecilia, a look of quiet worry on her face. He then looked right—and up, at the quiet face of Master Bacon.

“God understands you are frustrated, Majesty,” the tutor knelt down, and gently took Andronikos’ now shaking hands. “But

you must understand that God can see things that you cannot, and there is a reason, and a purpose, for all things under heaven!”

“But Master Bacon,” Andronikos said, his voice cracking. He cursed. He didn’t want his voice to crack! Why was his voice cracking now! “You always said we should try to understand the world around us! That…”

“Understanding the world means understanding that there are limits to our understanding,” the monk went on gently. “That there are things, no matter how hard we try, we will never know. A wise man accepts that, even as he pushes the sphere of his knowledge as far as it will go. Only a fool thinks he can know all.”

“Am I a fool?” Andronikos whispered, a tear coursing down his cheek.

“You are anything but a fool,” Bacon smiled, patting him on the head in an entirely unregal manner.

“You’re a lazy bum!” a voice echoed. Andronikos sniffed, then looked up ahead of the trio. Hand on his hip, triumphantly holding a brace of hares aloft, was a smirking Ioannis Angelos. “I had to catch

all the hares, Andie! All of them!” the boy bellowed, smiling despite his bellicose words. “Get out of that swampy talk of yours and help me skin them!”

==========*==========

So, our dear little Andronikos has major problems with God, as well as the need to keep his true desires, even simple boyhood wishes, secret because he’s now the Emperor. Will he crack under the strain? Or will he rise to the occasion? And how will having an education from the father of the scientific method affect him? Next, we travel to Spain, where Segeo’s fate will be made plain—but not before a brief stop at a villa in Konstantinopolis...