Rome AARisen - a Byzantine AAR

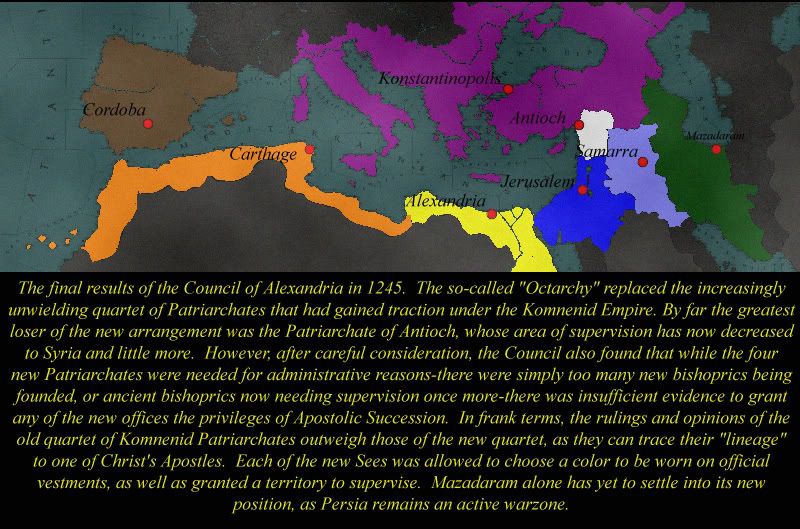

- Thread starter General_BT

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

That's a long list

Can you imagine a complete list at the end of the HoI part? (HoI because we all know this is gonna continue to the end. It's to epic to end at EU.

I think there is an utility that can automatically generate a family tree - you load the savegame file, put in the ID of a character and run it.

It has taken me 1 and a half weeks to read this entire AAR amd I am Throughly thrilled, will the Komenids rule Byzantium throught history?

It has taken me 1 and a half weeks to read this entire AAR amd I am Throughly thrilled, will the Komenids rule Byzantium throught history?

That map on the page back there may or may not answer that question. And it may or may not crush your dreams.

By the Gods! I've finally finished!

My review: excellent, fantastic, incredible!

How long it took me to finish: January 29th - February 17th

I now have a feeling of emptiness that can only be satisfied by more Romans.

I WANT MOAR!!!!!!!!!

My review: excellent, fantastic, incredible!

How long it took me to finish: January 29th - February 17th

I now have a feeling of emptiness that can only be satisfied by more Romans.

I WANT MOAR!!!!!!!!!

Kirsch27 - The wait is over!

Tommy4ever - See above. Now you join the ranks of everyone that has to wait for their next fix. At least you haven't joined the ranks of the people creating the fix. :rofl:

Now you join the ranks of everyone that has to wait for their next fix. At least you haven't joined the ranks of the people creating the fix. :rofl:

Avalanchemike - Or not, if you're looking for a fun EU3 scenario!

Morrell8 - Depends. If you mean "Will someone with the blood of the MEgas in their veins rule Byzantium?" then the answer will be yes. However, that answer is very very very broad.

Winner - Yup. I used it a while back on the family tree, but for the life of me can't think of the name at the moment... *puzzled*

Vesimir - Um, no. Will not happen, mostly because I'm not a maschochist.

RGB - Suitable and took forever to create!

Siind, Laur and Hannibal X -Haven't decided about SE Asia yet. Chances are that's an area I"m going to chuck to the other people helping with the mod once it gets going...

armoristan - Sadly, I think that AAR is likely dead--mostly because a)I lack the motivation, and b) I don't know where the save has gone...

von Sachsen - Well, keep in mind alot of those little states are vassals of other states in the Komnenid case...

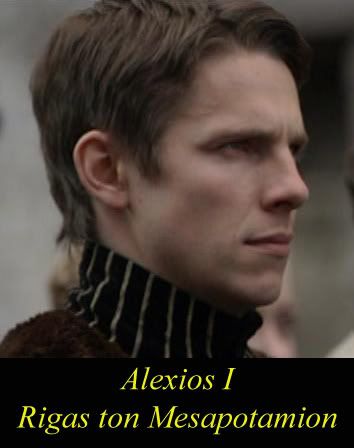

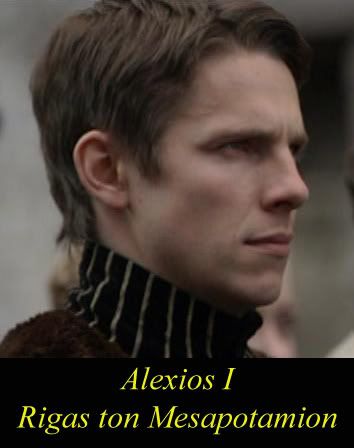

“There is no greater fallacy than glory in battle, or beauty in war. Even if the Megas spoke of such things, I call them callous, even foolish.” – Alexios I, King of Mesopotamia, in a letter to his father, Prince Adrianos of Edessa.

Alexios of Mesopotamia

March 4th, 1247

Ever since the Komnenid conquest, few would be willing to call Baghdad a quiet city. As the heart of Muslim art, learning, and civilization for the entire Middle East, it’d never been a quiet city. True, the cries of religious unhappiness rang anew amongst the Syriac Christians and Muslims of the city, all unhappy about the new Patriarchate of Samarra’s efforts at conversion, but Alexios had heard them before. Indeed, he felt for them—especially the Syriac Christians. While Patriarch Simon had seemed inclined to be patient in converting the vast number of Muslims between the Two Rivers, he’d ruthlessly sent agents and men after the Syriac Church of the realm, arresting leaders and looting churches. In 1246 the affairs had grown so far out of hand that Alexios was forced to intervene personally with his own guardsmen, blocking the Patriarch’s agents from entering several of the prominent remaining churches while the King himself, fresh with authority, wrote to Konstantinopolis to complain.

That thought made Alexios smile—oh the howl of protest from Samarra, and the thanks he received from the Syriacs! Alexios agreed they should convert to True Orthodoxy—to deny the Nicene Creed meant one was a heretic, no more, no less—but to convert by fire and sword? And most importantly, outside the bounds of state and law? Alexios, like all the Komnenoi so far, saw that as more of an affront to God’s holy word, and the divinely appointed order of things.

However, as he rode his horse through the ornate gates of the city, a shadow of his stallion’s hoofbeats following, other noises assaulted his ears, ones far different from the complaints of Patriarchs and commons alike. The rhythmic clang of hammers on steel, the strong bellow of a kentarchos ordering sloppy recruits into line, the drum of feet marching on the spring earth. The King of Mesopotamia sighed, reining up his horse. He looked all of his 19 years, and almost unregally at that. The young man wasn’t particularly tall, and even after years of training on the horse he still slightly slouched in the saddle. His doublet and fine robes seemed almost too big for his slight frame—if one had not known, it would be easy to assume he was a gawking son of a minor noble, not the King of Mesopotamia. His thin, almost hawklike face marked him as a member of the Edessan branch of the Komnenoi forest—a descendant of Christophoros Komnenos, son of the Megas . Frank, open eyes glanced around him, watching the sights of a vast camp of men training for war, banners fluttering in the wind like silken shards of glory to come.

Glory Alexios thought was pure, utter nonsense. The Komnenid line had been built on glory, yes, and one could even say Alexios’ own rise to prominence out of the shadows of being his father’s puppet was owed to ‘glory,’ of a sort. That thought made the young King snort even more. Many of the soon to be soldiers being put through their paces around him—Arabs, Persians, a few Romans even—thought they were off on some adventure, to save their faith, or their people, whatever those might be, from the hungry Mongol. Alexios knew they were simply more men, more fodder, for the so-called Eternal War.

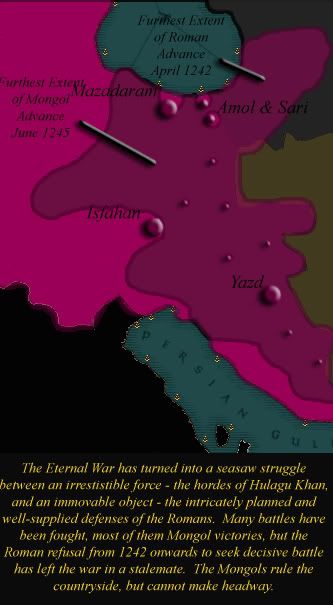

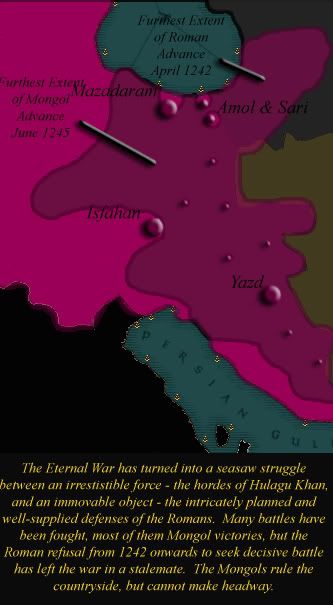

When Hulagu Khan had launched his initial hammerblow into Persia in the fall of 1240, the Mongol had expected a short war—he hadn’t counted on Emperor Gabriel moving nearly 90,000 men north, nor the massive levies and garrisons that filled every border fortress the Mongol invasion force would need to take. 15,000 of his men paid for his mistakes with their lives outside of Sari, when Gabriel’s army surprised half of Hulagu’s force. Emperor Gabriel immediately tried to launch a pursuit as Hulagu backpedaled out of Persia, army disorganized and in disarray.

Yet the Roman Emperor, too, had miscalculated the war as well. Racing north to deliver what he hoped would be a deathblow to any future attacks by the Mongols, Gabriel’s army left a long, tenuous supply line behind them. In the south, Gabras’ holding force was annihilated by Hulagu’s son Guyuk outside of Yazd. Nearly 15,000 Romans and allies, including the bulk of the Herculare and Scholarae tagmata were slain or captured, and Prince Gabras himself was taken captive, blinded, then strangled with a bowstring. Even as the Emperor lunged towards the Oxus, another unknown entered into the fray…

No one—not Gabriel, not Adrianos, not Thomas Dadiani—had ever heard the name Altani spoken before. Yet it was Hulagu’s daughter, if the rumors were to be believed, that tongue-lashed her father into stopping his retreat and making a stand on the Oxus in the spring of 1241. While Gabriel and Hulagu skirmished throughout April and May of 1241, Altani, along with her godfather the famous Subotai, lead a small force of half a tumen around the Roman army, burning the main Roman supply depot outside of Ashgabat. Cut off without supplies, the Romans were forced to spend the summer of 1241 in a scorching, miserable retreat. Emperor Gabriel lost another 20,000 soldiers to heat and thirst, all while Hulagu’s still extensive force nipped at his heels.

On their heels, with losses mounting, Gabriel Komnenos did the unthinkable.

Alexios was old enough to remember his advisors commenting bitterly on the Emperor’s choice—the King could only imagine how Gabriel’s subordinates must have howled when he announced the Romans would retire to their well-stocked fortresses and refuse battle with the Mongols. On the surface, the move seemed like madness—the Romans had always sought battle as the way to end a war! It had been the way the Megas and the Megaloprepis had resolved their conflicts! Decisive battle, decisive victories—such was the Komnenid way! To not offer battle? It was an idea that simply didn’t enter the mind of most of the Roman commanders.

Despite their howls and complaints, the Romans and their allies and levies did exactly that. Throughout 1242 and 1243, Hulagu repeatedly offered battle—he would threaten a strategic city, show a flank of his army on the march, anything, all in an effort to get Gabriel to come and fight the Mongols on their terms. Each time, every time, the Romans refused, instead sending the Turks under their peerless Sultan to raid the steadily growing Mongol supply line. True, the famous tumen could subsist off the land, but not the tens of thousands of levies that came with Hulagu’s force—the Chinese manning the siege train, the Korean infantry that would storm the walls. They needed food and fodder brought to them. Every time the Mongols settled to siege an important city—Rayy, Amol, Isfahan even, the Turks would harass their supplies, and deftly avoid pursuit.

The war settled into a plodding, bloody stalemate. The Mongols rushed about, sieging towns while their tumen scoured the countryside. The Romans stood their ground, while the Turks danced around the tumen and harassed and raided. Altani, Hulagu and Subotai had been victorious in every three of four battles they have fought, including Roman debacles at Khorrol, Hormizd, and Mashad. At one point, the Mongols held treks of countryside stretching to near the Zagros, and Mongol raiding parties crossed the mountains and attacked villages on the Tigris. Yet for all their battlefield brilliance, the Mongols could not deliver the knockout blow in the face of Roman stubbornness. For three years Isfahan, Fortress of the East, has held out against the besieging Mongol forces, and Amol, Sari and Rayy have all proven troublesome thorns in the Mongol flank. Without a Roman army to destroy, Hulagu has been left master of the countryside, but cannot hold any of his gains.

So, the Eternal War continued, a war of sieges and skirmishes, not grand battles and decisive campaigns. A war that, for most of Alexios’ life, seemed distant, on the horizon, until that fateful summer two years before, when what was supposed to be a tour of ‘safe forts’ in northern Persia organized by his father went horribly awry…

“Steel yourself, husband, here he comes.”

Alexios glanced behind to the source of the warning and nodded. Most Roman men would have quailed at letting their wife ride with them through the fields of a gathering army—they would fear the weaker sex would have been overwhelmed by the sights and sounds, or they feared the leering gaze of a prole on their woman. Especially a woman of the beauty of Anastasia Komnenos, sister to Emperor Nikephoros IV. She had the aquiline nose of the Spanish Komnenids, something one often didn’t find amongst the women of Konstantinopolis. When she moved, it was with the grace and gentleness of a deer—even if her belly was distended with their second child. Alexios counted himself fortunate—few men could boast they had a wife of matching looks.

But if one thing was true of Anastasia Komnenos, it was that she held no fear. Anyone who saw her actions when a Mongol raiding force looted the countryside around Basra, with her inside, would testify to that. If a second thing was true of the Queen of Mesopotamia, it was that she would take care of herself. Anastasia was a tomboy while young, and her grace in movements hid power and purpose. While she and Alexios grew up together in court at Baghdad, it was she, not his armsmen, that showed him the dangerous Spanish grip and the Cordoban parry. The King pitied any fool who thought he could overpower her!

Besides, Alexios thought watching the man that compelled them to be here this day instead of curled in bed next to one another, Anastasia was his shield against a sword of a different kind. She had one of the quickest minds he’d ever seen, and Alexios trusted her judgment implicitly. Perhaps his own Logothetes had a point that she was impetuous at times, maybe even rash with her pronouncements, but the King certainly would never hold Council without her present—let alone meet Eleutherios Skleros.

“Master Skleros,” Alexios said quietly as the black robed rider reined up in front of him and the Queen. The King secretly thanked his Logothetes for the five minute warning that not just any visitor from Konstantinopolis was coming…

“Majesty,” the Greek smiled slightly, giving the proper, polite bow of deference. It was far more respectful than most bows direct Alexios’ way—he was, in reality, still a “puppet” for his father. As the King watched, Skleros’ eyes flecked over to Anastasia, and the smile grew slightly colder. “Majesty. Word of your beauty in Konstantinopolis does not do you justice.”

“Word of you in Baghdad does not do you justice either,” Anastasia responded, her smile an icy contrast to her warm words. “Your visit is an unexpected… pleasure,” she added, the last word dragged out of her mouth unwillingly by protocol.

“Indeed?” Skleros arched an eyebrow.

“Yes,” Alexios added, deciding to follow his wife’s tack, “We were told an emissary from the Megoskyriomachos would arrive today, and not your own… august… person. Your reputation proceeds you.”

Most men should have taken Alexios’ words as a compliment, But Skleros? The man’s reputation was blacker than the night! Two weeks after he visited the Prince of Galilee, the man died of apoplexy during the middle of dinner. The day he arrived in the court of Prince Michael of Antioch, the old fool tripped off a balcony into the streets below. Where-ever he went, death was in his wings. If the King had any real power, or any real notice, he would’ve barred the borders before letting the man into Baghdad!

“Ah, good,” Skleros said in reply, that same cold, damning smile on his lips. Clearly he knew, and he was pleased Alexios and his wife knew as well. “His Lordship has taken a… personal… interest in the goings on here in Baghdad.”

“Indeed?” Alexios asked, blood turning to ice. So Skleros was here, on the orders of the Megoskyriomachos personally? The King fought the urge to worriedly look over at his wife, and her urgently distended belly. Anastasia swore she was carrying a son.

“Indeed,” Skleros’ smile faded into a more serious look. “Lord von Franken, like every good Roman, has a keen interest in the successful end of the Mongol War. I’ve been dispatched to observe the condition of the soldiers you are raising, as well as food and supplies, and report back to His Lordship forthwith.” Those fangs returned again. “He is most keen to see how efficiently your granaries are being stocked. There are reports of merchants in Antioch using the…power arrangement,” the smile faded slightly at those words, “to hike prices.”

Ah… so that was his cover, Alexios thought. There normally wouldn’t be any reason to explain why someone like Eleutherios Skleros would have left the confines of Thomas III’s section of the Empire for Mesopotamia, technically an independent client kingdom. How fortunate, Alexios reasoned, that Gabriel Komnenos, after four years of hiding behind walls and stratagems, was finally going to seek battle—and seeking battle meant vast amounts of grain pouring into Mesopotamia, which was rapidly becoming the marshalling ground for the offensive.

The four bloody years of nibbling and pecking had shown the Mongol horde has numerous weaknesses. Firstly, for all the power of the Mongol tumen, the levies, those trained men who knew the art of siegecraft, were the ones that were decisive. Whenever their fodder, equipment and supplies were disrupted, the Mongol hordes were forced to break off the siege. Second, the tumen themselves were not what they used to be. Years of warfare and empire-building had spread the Mongol armies thin. Of the eight tumen that had thundered into Persia seven years before, only four were really performing as well as the tumen of Genghis Khan—chiefly because those four were the only tumen that were truly Mongol. The others had been hastily assembled from a mismatch of steppe tribes that were allies or subjects of the Great Khan, all with varying degrees of competence. While Guyuk Khan’s Kara Kitai tumen had proven formidable, Bertei’s Jurchen, despite their commander’s best efforts, were clearly more interested in looting and pillaging than battle and discipline.

Together there was enough evidence indicating the Mongols were not only weakened by losses—50,000 in over seven years—but cohesion that the Emperor could break his infamous policy. But to do so, he would need reinforcements—thousands of them, both trained and untrained. Alexios could already imagine the cold logic—even the most untrained levy could take an arrow meant for a trained soldier of the tagmata.

Levies Alexios was raising.

Levies Alexios now realized one Gabriel Komnenos, also threatened by the child in Anastasia’s belly, had told Albrecht von Franken about, giving Skleros all the reason he needed to “visit.”

“I, too, have heard those reports,” Alexios said slowly. Those men had already been dealt with by his father. There had been price gouging taking place. No more.

“How many do you have here?” Skleros blithely went onwards, looking over the sea of tents, barking kentarchoi and battleflags.

“One full dianomi, three tagmata strong,” Alexios said grimly, the full depth of his predicament obvious, “with another partial tagmata as well.” He’d been assigned to raise three dianomi, or nine tagmata—nearly 30,000 troops. Instead, he’d be reporting to his cousin and father with a little over 10,000. Mesopotamia too, it seemed, was being bled out by the Eternal War.

Skleros clucked grimly, shaking his head. “Well,” the older man pursed his lips and sighed, “we can only hope you can make miracles with them like you did at Sari.”

Alexios nodded quietly, casting a sideways glance at his wife. By the barest smile on her face, he knew she was pleased he hadn’t winced like he normally did when people uttered the name ‘Sari.’ No matter who Alexios complained to, or castigated, or shouted to the heavens that the battle-plan had been entirely made by his fallen Megos Domestikos, or that Sari in the grand scheme of things was a very large skirmish, not a decisive battle, everyone still only remembered how the then 16 year old King of Mesopotamia, the puppet whose handlers and minders had almost forbade him to don a suit of armor, had led the final charge of his Mesopotamian kataphraktoi that broke half of the tumen of the fearsome Guyuk Khan.

He didn’t order the charge—he wasn’t sure who did in fact. It was merely one tiny detail lost in a tapestry of gore. They were surrounded, the men were crying there was no other choice. One second there were arguments over what to do, the next people had spurred their horses at the charging Mongols, lances down, battlecries in the air. Alexios had never intended to end up in front either, but after Chillarchos Fahraz went down…

Alexios still shook thinking of that day, the fear that rushed through his mind, the screams, the sword-strokes—it was all a blur. Yet, in a war that never seemed to end, it’d made him, a nonentity, into a legend overnight. Already, the shy, reserved Alexios had honors heaped onto his head, and responsibilities thrown onto his lap. The fact that he knew Farsi and Arabic meant his cousin Gabriel wanted him to spearhead conscription amongst the natives, while his popularity meant his father wanted him to recruit more Romans for Persian service. Their needs combined meant that since that day, he’d been a busy young man—far busier than he’d hoped.

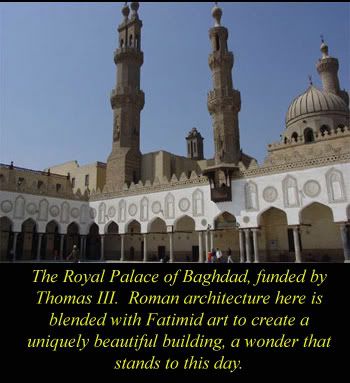

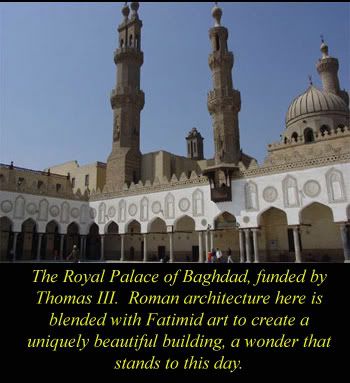

He’d have rather stayed in Baghdad, enjoying time with his wife, and overseeing the new construction projects paid for by his distant cousin in Konstantinopolis. Not overseeing new levies, or hosting poisonous guests.

“God willing,” Alexios finally muttered a reply, spurring his horse forward slightly. He needed time to think! To think! If Skleros was here because of Anastasia’s child… The king winced as the hooves of Skleros’ and Anastasia’s horses followed. “They aren’t well trained yet, My Lord,” the King admitted, trying to get his mind back to the present, “but they’ll mostly be light foot. We’ve got no armor to spare for them, and the barest of shields, but thanks to Anastasia’s father,” Alexios nodded to his wife, “we’ve javelins aplenty. It seems if the Spanish know how to make one thing, it’s javelins.”

“And Almogavars,” Anastasia added, the smile on her face brilliant, dragging Alexios’ own grim mind out into slivers of a bright sunshine. She always did that for him—ever since they’d been introduced, all those years ago. He’d been a shy 12 year old, a puppet king dragged from his father and surrounded by strange men running things for him. She’d been a 13 year old hothead, sister to an equally hotheaded and young Emperor Nikephoros. The two opposites had clicked immediately—Alexios openly told people that on the day of their final wedding, three years before, he was marrying his best friend, a sentiment he knew Anastasia would heartily agree with.

“I see,” Skleros nodded towards a group of the greasy, fur-capped men of Spain who were fingering around with a box of javelins. Even in horseplay, they looked dangerous with the weapons. Alexios hoped they’d impart some of that skill onto the levies.

“And, children too,” Skleros turned and smiled towards Anastasia, the same cold, empty smile he’d shown Alexios earlier. The King now visibly winced—Eleutherios was a blunt one.

“Hopefully a son,” Alexios watched as Anastasia met Skleros’ gaze fearlessly. She too knew why he was here, and wasn’t about to show her fear. Alexios’ father might be actually in control of Mesopotamia for now, but once Adrianos Komnenos passed into the next world, Alexios Komnenos would be King of Mesopotamia, Despotes of Syria, as well as Prince of Edessa and Coloneia. If Anastasia bore a son, and her brother did not sire one of his own…

The Western Empire, plus Mesopotamia, plus Syria and Coloneia. The delicate balance that had kept the peace between the West, the Center, and the East would be disrupted. One man would control lands from Cordoba to Baghdad, and only a fool would miss the simple temptation for someone with that much power, that much land, to march to take Egypt from Gabriel and Konstantinopolis from von Franken…

“We all pray for an heir,” Skleros’ smile held solid and firm as a glacier. “My master, as well as Emperor Thomas, both pray daily for the safe delivery of your unborn child.”

“Thank you for your kindness,” Alexios tried to put on a pleasant smile. He knew he probably failed. “We too pray, for a son to be an heir to myself, my father, and Emperor Nikephoros.”

“Ah yes,” Skleros bared his fangs in a smile. “But Majesty, back to the business at hand,” he said pleasantly enough, “I will be requiring accommodations for two weeks while I finish my observations and write my reports for Konstantinopolis. From what I’ve seen, you are accomplishing much here in the war effort.”

Alexios’ heart leapt to his throat. The snake was staying two weeks?

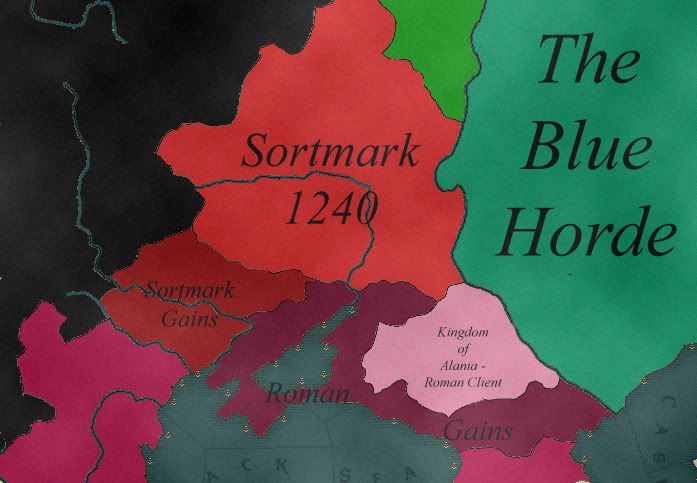

“Almost as much as King Knud accomplished last summer when he threw off the Mongol yoke,” Skleros went on. Skleros’ master had spent four years engineering a coup across the Black Sea. First, von Franken had bribed/cajoled/pushed the sons of the Danish Grand Duke into counseling their father into declaring himself King and formally divesting himself of his Mongol overlords. Then, once the Blue Horde panicked (for most of its forces were with Hulagu, on the orders of the Great Khan in Karakorum), von Franken offered Batu Khan a deal—Romanion would not support the Danes militarily, if the Romans were allowed to retake their lost TransPontic lands. The Romans, with a partial tagma and 10,000 thematakoi forcibly annexed the “Grand Principality of Cherson,” in 1246, while the Danes thumped the remaining tumen of Batu Khan at Cherniye Ozero, then promptly celebrated by seizing the lands of the former “Prince of Pereslavyl,” including the remains of their once magnificent capital at Havigraes. Reportedly the Emperor in Konstantinopolis sent the Danish King a gift of 4 tons of marble and 100 tons of granite, to make sure his palace was built of stone this time.

The plan had gone splendidly for all parties involved, save the Blue Horde.

“I thank Your Lordship for your kindness,” Alexios murmured, suddenly feeling naked and vulnerable despite his armor, title, and the army of men currently surrounding them. “Um...my stewards shall find suitable accommodation for you.”

“Thank you. I think,” Skleros added, turning his horse back towards the gates of the city, “I shall leave Your Majesty to the business at hand while I begin writing my reports and conduct some more tours of your camps. There is certainly no rest for the wicked, is there?” That smile somehow grew larger. “Good day, Your Majesty,” he bowed slightly to Alexios, before turning to Anastasia. “Majesty.”

So we’ve moved along quite a bit. Gabriel and the Mongols are at an impasse, while Nikephoros and Adrianos’ deal is now known—a marriage that could rock the political foundations of Romanion…

Tommy4ever - See above.

Avalanchemike - Or not, if you're looking for a fun EU3 scenario!

Morrell8 - Depends. If you mean "Will someone with the blood of the MEgas in their veins rule Byzantium?" then the answer will be yes. However, that answer is very very very broad.

Winner - Yup. I used it a while back on the family tree, but for the life of me can't think of the name at the moment... *puzzled*

Vesimir - Um, no. Will not happen, mostly because I'm not a maschochist.

RGB - Suitable and took forever to create!

Siind, Laur and Hannibal X -Haven't decided about SE Asia yet. Chances are that's an area I"m going to chuck to the other people helping with the mod once it gets going...

armoristan - Sadly, I think that AAR is likely dead--mostly because a)I lack the motivation, and b) I don't know where the save has gone...

von Sachsen - Well, keep in mind alot of those little states are vassals of other states in the Komnenid case...

“There is no greater fallacy than glory in battle, or beauty in war. Even if the Megas spoke of such things, I call them callous, even foolish.” – Alexios I, King of Mesopotamia, in a letter to his father, Prince Adrianos of Edessa.

Alexios of Mesopotamia

March 4th, 1247

Ever since the Komnenid conquest, few would be willing to call Baghdad a quiet city. As the heart of Muslim art, learning, and civilization for the entire Middle East, it’d never been a quiet city. True, the cries of religious unhappiness rang anew amongst the Syriac Christians and Muslims of the city, all unhappy about the new Patriarchate of Samarra’s efforts at conversion, but Alexios had heard them before. Indeed, he felt for them—especially the Syriac Christians. While Patriarch Simon had seemed inclined to be patient in converting the vast number of Muslims between the Two Rivers, he’d ruthlessly sent agents and men after the Syriac Church of the realm, arresting leaders and looting churches. In 1246 the affairs had grown so far out of hand that Alexios was forced to intervene personally with his own guardsmen, blocking the Patriarch’s agents from entering several of the prominent remaining churches while the King himself, fresh with authority, wrote to Konstantinopolis to complain.

That thought made Alexios smile—oh the howl of protest from Samarra, and the thanks he received from the Syriacs! Alexios agreed they should convert to True Orthodoxy—to deny the Nicene Creed meant one was a heretic, no more, no less—but to convert by fire and sword? And most importantly, outside the bounds of state and law? Alexios, like all the Komnenoi so far, saw that as more of an affront to God’s holy word, and the divinely appointed order of things.

However, as he rode his horse through the ornate gates of the city, a shadow of his stallion’s hoofbeats following, other noises assaulted his ears, ones far different from the complaints of Patriarchs and commons alike. The rhythmic clang of hammers on steel, the strong bellow of a kentarchos ordering sloppy recruits into line, the drum of feet marching on the spring earth. The King of Mesopotamia sighed, reining up his horse. He looked all of his 19 years, and almost unregally at that. The young man wasn’t particularly tall, and even after years of training on the horse he still slightly slouched in the saddle. His doublet and fine robes seemed almost too big for his slight frame—if one had not known, it would be easy to assume he was a gawking son of a minor noble, not the King of Mesopotamia. His thin, almost hawklike face marked him as a member of the Edessan branch of the Komnenoi forest—a descendant of Christophoros Komnenos, son of the Megas . Frank, open eyes glanced around him, watching the sights of a vast camp of men training for war, banners fluttering in the wind like silken shards of glory to come.

Glory Alexios thought was pure, utter nonsense. The Komnenid line had been built on glory, yes, and one could even say Alexios’ own rise to prominence out of the shadows of being his father’s puppet was owed to ‘glory,’ of a sort. That thought made the young King snort even more. Many of the soon to be soldiers being put through their paces around him—Arabs, Persians, a few Romans even—thought they were off on some adventure, to save their faith, or their people, whatever those might be, from the hungry Mongol. Alexios knew they were simply more men, more fodder, for the so-called Eternal War.

When Hulagu Khan had launched his initial hammerblow into Persia in the fall of 1240, the Mongol had expected a short war—he hadn’t counted on Emperor Gabriel moving nearly 90,000 men north, nor the massive levies and garrisons that filled every border fortress the Mongol invasion force would need to take. 15,000 of his men paid for his mistakes with their lives outside of Sari, when Gabriel’s army surprised half of Hulagu’s force. Emperor Gabriel immediately tried to launch a pursuit as Hulagu backpedaled out of Persia, army disorganized and in disarray.

Yet the Roman Emperor, too, had miscalculated the war as well. Racing north to deliver what he hoped would be a deathblow to any future attacks by the Mongols, Gabriel’s army left a long, tenuous supply line behind them. In the south, Gabras’ holding force was annihilated by Hulagu’s son Guyuk outside of Yazd. Nearly 15,000 Romans and allies, including the bulk of the Herculare and Scholarae tagmata were slain or captured, and Prince Gabras himself was taken captive, blinded, then strangled with a bowstring. Even as the Emperor lunged towards the Oxus, another unknown entered into the fray…

No one—not Gabriel, not Adrianos, not Thomas Dadiani—had ever heard the name Altani spoken before. Yet it was Hulagu’s daughter, if the rumors were to be believed, that tongue-lashed her father into stopping his retreat and making a stand on the Oxus in the spring of 1241. While Gabriel and Hulagu skirmished throughout April and May of 1241, Altani, along with her godfather the famous Subotai, lead a small force of half a tumen around the Roman army, burning the main Roman supply depot outside of Ashgabat. Cut off without supplies, the Romans were forced to spend the summer of 1241 in a scorching, miserable retreat. Emperor Gabriel lost another 20,000 soldiers to heat and thirst, all while Hulagu’s still extensive force nipped at his heels.

On their heels, with losses mounting, Gabriel Komnenos did the unthinkable.

Alexios was old enough to remember his advisors commenting bitterly on the Emperor’s choice—the King could only imagine how Gabriel’s subordinates must have howled when he announced the Romans would retire to their well-stocked fortresses and refuse battle with the Mongols. On the surface, the move seemed like madness—the Romans had always sought battle as the way to end a war! It had been the way the Megas and the Megaloprepis had resolved their conflicts! Decisive battle, decisive victories—such was the Komnenid way! To not offer battle? It was an idea that simply didn’t enter the mind of most of the Roman commanders.

Despite their howls and complaints, the Romans and their allies and levies did exactly that. Throughout 1242 and 1243, Hulagu repeatedly offered battle—he would threaten a strategic city, show a flank of his army on the march, anything, all in an effort to get Gabriel to come and fight the Mongols on their terms. Each time, every time, the Romans refused, instead sending the Turks under their peerless Sultan to raid the steadily growing Mongol supply line. True, the famous tumen could subsist off the land, but not the tens of thousands of levies that came with Hulagu’s force—the Chinese manning the siege train, the Korean infantry that would storm the walls. They needed food and fodder brought to them. Every time the Mongols settled to siege an important city—Rayy, Amol, Isfahan even, the Turks would harass their supplies, and deftly avoid pursuit.

The war settled into a plodding, bloody stalemate. The Mongols rushed about, sieging towns while their tumen scoured the countryside. The Romans stood their ground, while the Turks danced around the tumen and harassed and raided. Altani, Hulagu and Subotai had been victorious in every three of four battles they have fought, including Roman debacles at Khorrol, Hormizd, and Mashad. At one point, the Mongols held treks of countryside stretching to near the Zagros, and Mongol raiding parties crossed the mountains and attacked villages on the Tigris. Yet for all their battlefield brilliance, the Mongols could not deliver the knockout blow in the face of Roman stubbornness. For three years Isfahan, Fortress of the East, has held out against the besieging Mongol forces, and Amol, Sari and Rayy have all proven troublesome thorns in the Mongol flank. Without a Roman army to destroy, Hulagu has been left master of the countryside, but cannot hold any of his gains.

So, the Eternal War continued, a war of sieges and skirmishes, not grand battles and decisive campaigns. A war that, for most of Alexios’ life, seemed distant, on the horizon, until that fateful summer two years before, when what was supposed to be a tour of ‘safe forts’ in northern Persia organized by his father went horribly awry…

“Steel yourself, husband, here he comes.”

Alexios glanced behind to the source of the warning and nodded. Most Roman men would have quailed at letting their wife ride with them through the fields of a gathering army—they would fear the weaker sex would have been overwhelmed by the sights and sounds, or they feared the leering gaze of a prole on their woman. Especially a woman of the beauty of Anastasia Komnenos, sister to Emperor Nikephoros IV. She had the aquiline nose of the Spanish Komnenids, something one often didn’t find amongst the women of Konstantinopolis. When she moved, it was with the grace and gentleness of a deer—even if her belly was distended with their second child. Alexios counted himself fortunate—few men could boast they had a wife of matching looks.

But if one thing was true of Anastasia Komnenos, it was that she held no fear. Anyone who saw her actions when a Mongol raiding force looted the countryside around Basra, with her inside, would testify to that. If a second thing was true of the Queen of Mesopotamia, it was that she would take care of herself. Anastasia was a tomboy while young, and her grace in movements hid power and purpose. While she and Alexios grew up together in court at Baghdad, it was she, not his armsmen, that showed him the dangerous Spanish grip and the Cordoban parry. The King pitied any fool who thought he could overpower her!

Besides, Alexios thought watching the man that compelled them to be here this day instead of curled in bed next to one another, Anastasia was his shield against a sword of a different kind. She had one of the quickest minds he’d ever seen, and Alexios trusted her judgment implicitly. Perhaps his own Logothetes had a point that she was impetuous at times, maybe even rash with her pronouncements, but the King certainly would never hold Council without her present—let alone meet Eleutherios Skleros.

“Master Skleros,” Alexios said quietly as the black robed rider reined up in front of him and the Queen. The King secretly thanked his Logothetes for the five minute warning that not just any visitor from Konstantinopolis was coming…

“Majesty,” the Greek smiled slightly, giving the proper, polite bow of deference. It was far more respectful than most bows direct Alexios’ way—he was, in reality, still a “puppet” for his father. As the King watched, Skleros’ eyes flecked over to Anastasia, and the smile grew slightly colder. “Majesty. Word of your beauty in Konstantinopolis does not do you justice.”

“Word of you in Baghdad does not do you justice either,” Anastasia responded, her smile an icy contrast to her warm words. “Your visit is an unexpected… pleasure,” she added, the last word dragged out of her mouth unwillingly by protocol.

“Indeed?” Skleros arched an eyebrow.

“Yes,” Alexios added, deciding to follow his wife’s tack, “We were told an emissary from the Megoskyriomachos would arrive today, and not your own… august… person. Your reputation proceeds you.”

Most men should have taken Alexios’ words as a compliment, But Skleros? The man’s reputation was blacker than the night! Two weeks after he visited the Prince of Galilee, the man died of apoplexy during the middle of dinner. The day he arrived in the court of Prince Michael of Antioch, the old fool tripped off a balcony into the streets below. Where-ever he went, death was in his wings. If the King had any real power, or any real notice, he would’ve barred the borders before letting the man into Baghdad!

“Ah, good,” Skleros said in reply, that same cold, damning smile on his lips. Clearly he knew, and he was pleased Alexios and his wife knew as well. “His Lordship has taken a… personal… interest in the goings on here in Baghdad.”

“Indeed?” Alexios asked, blood turning to ice. So Skleros was here, on the orders of the Megoskyriomachos personally? The King fought the urge to worriedly look over at his wife, and her urgently distended belly. Anastasia swore she was carrying a son.

“Indeed,” Skleros’ smile faded into a more serious look. “Lord von Franken, like every good Roman, has a keen interest in the successful end of the Mongol War. I’ve been dispatched to observe the condition of the soldiers you are raising, as well as food and supplies, and report back to His Lordship forthwith.” Those fangs returned again. “He is most keen to see how efficiently your granaries are being stocked. There are reports of merchants in Antioch using the…power arrangement,” the smile faded slightly at those words, “to hike prices.”

Ah… so that was his cover, Alexios thought. There normally wouldn’t be any reason to explain why someone like Eleutherios Skleros would have left the confines of Thomas III’s section of the Empire for Mesopotamia, technically an independent client kingdom. How fortunate, Alexios reasoned, that Gabriel Komnenos, after four years of hiding behind walls and stratagems, was finally going to seek battle—and seeking battle meant vast amounts of grain pouring into Mesopotamia, which was rapidly becoming the marshalling ground for the offensive.

The four bloody years of nibbling and pecking had shown the Mongol horde has numerous weaknesses. Firstly, for all the power of the Mongol tumen, the levies, those trained men who knew the art of siegecraft, were the ones that were decisive. Whenever their fodder, equipment and supplies were disrupted, the Mongol hordes were forced to break off the siege. Second, the tumen themselves were not what they used to be. Years of warfare and empire-building had spread the Mongol armies thin. Of the eight tumen that had thundered into Persia seven years before, only four were really performing as well as the tumen of Genghis Khan—chiefly because those four were the only tumen that were truly Mongol. The others had been hastily assembled from a mismatch of steppe tribes that were allies or subjects of the Great Khan, all with varying degrees of competence. While Guyuk Khan’s Kara Kitai tumen had proven formidable, Bertei’s Jurchen, despite their commander’s best efforts, were clearly more interested in looting and pillaging than battle and discipline.

Together there was enough evidence indicating the Mongols were not only weakened by losses—50,000 in over seven years—but cohesion that the Emperor could break his infamous policy. But to do so, he would need reinforcements—thousands of them, both trained and untrained. Alexios could already imagine the cold logic—even the most untrained levy could take an arrow meant for a trained soldier of the tagmata.

Levies Alexios was raising.

Levies Alexios now realized one Gabriel Komnenos, also threatened by the child in Anastasia’s belly, had told Albrecht von Franken about, giving Skleros all the reason he needed to “visit.”

“I, too, have heard those reports,” Alexios said slowly. Those men had already been dealt with by his father. There had been price gouging taking place. No more.

“How many do you have here?” Skleros blithely went onwards, looking over the sea of tents, barking kentarchoi and battleflags.

“One full dianomi, three tagmata strong,” Alexios said grimly, the full depth of his predicament obvious, “with another partial tagmata as well.” He’d been assigned to raise three dianomi, or nine tagmata—nearly 30,000 troops. Instead, he’d be reporting to his cousin and father with a little over 10,000. Mesopotamia too, it seemed, was being bled out by the Eternal War.

Skleros clucked grimly, shaking his head. “Well,” the older man pursed his lips and sighed, “we can only hope you can make miracles with them like you did at Sari.”

Alexios nodded quietly, casting a sideways glance at his wife. By the barest smile on her face, he knew she was pleased he hadn’t winced like he normally did when people uttered the name ‘Sari.’ No matter who Alexios complained to, or castigated, or shouted to the heavens that the battle-plan had been entirely made by his fallen Megos Domestikos, or that Sari in the grand scheme of things was a very large skirmish, not a decisive battle, everyone still only remembered how the then 16 year old King of Mesopotamia, the puppet whose handlers and minders had almost forbade him to don a suit of armor, had led the final charge of his Mesopotamian kataphraktoi that broke half of the tumen of the fearsome Guyuk Khan.

He didn’t order the charge—he wasn’t sure who did in fact. It was merely one tiny detail lost in a tapestry of gore. They were surrounded, the men were crying there was no other choice. One second there were arguments over what to do, the next people had spurred their horses at the charging Mongols, lances down, battlecries in the air. Alexios had never intended to end up in front either, but after Chillarchos Fahraz went down…

Alexios still shook thinking of that day, the fear that rushed through his mind, the screams, the sword-strokes—it was all a blur. Yet, in a war that never seemed to end, it’d made him, a nonentity, into a legend overnight. Already, the shy, reserved Alexios had honors heaped onto his head, and responsibilities thrown onto his lap. The fact that he knew Farsi and Arabic meant his cousin Gabriel wanted him to spearhead conscription amongst the natives, while his popularity meant his father wanted him to recruit more Romans for Persian service. Their needs combined meant that since that day, he’d been a busy young man—far busier than he’d hoped.

He’d have rather stayed in Baghdad, enjoying time with his wife, and overseeing the new construction projects paid for by his distant cousin in Konstantinopolis. Not overseeing new levies, or hosting poisonous guests.

“God willing,” Alexios finally muttered a reply, spurring his horse forward slightly. He needed time to think! To think! If Skleros was here because of Anastasia’s child… The king winced as the hooves of Skleros’ and Anastasia’s horses followed. “They aren’t well trained yet, My Lord,” the King admitted, trying to get his mind back to the present, “but they’ll mostly be light foot. We’ve got no armor to spare for them, and the barest of shields, but thanks to Anastasia’s father,” Alexios nodded to his wife, “we’ve javelins aplenty. It seems if the Spanish know how to make one thing, it’s javelins.”

“And Almogavars,” Anastasia added, the smile on her face brilliant, dragging Alexios’ own grim mind out into slivers of a bright sunshine. She always did that for him—ever since they’d been introduced, all those years ago. He’d been a shy 12 year old, a puppet king dragged from his father and surrounded by strange men running things for him. She’d been a 13 year old hothead, sister to an equally hotheaded and young Emperor Nikephoros. The two opposites had clicked immediately—Alexios openly told people that on the day of their final wedding, three years before, he was marrying his best friend, a sentiment he knew Anastasia would heartily agree with.

“I see,” Skleros nodded towards a group of the greasy, fur-capped men of Spain who were fingering around with a box of javelins. Even in horseplay, they looked dangerous with the weapons. Alexios hoped they’d impart some of that skill onto the levies.

“And, children too,” Skleros turned and smiled towards Anastasia, the same cold, empty smile he’d shown Alexios earlier. The King now visibly winced—Eleutherios was a blunt one.

“Hopefully a son,” Alexios watched as Anastasia met Skleros’ gaze fearlessly. She too knew why he was here, and wasn’t about to show her fear. Alexios’ father might be actually in control of Mesopotamia for now, but once Adrianos Komnenos passed into the next world, Alexios Komnenos would be King of Mesopotamia, Despotes of Syria, as well as Prince of Edessa and Coloneia. If Anastasia bore a son, and her brother did not sire one of his own…

The Western Empire, plus Mesopotamia, plus Syria and Coloneia. The delicate balance that had kept the peace between the West, the Center, and the East would be disrupted. One man would control lands from Cordoba to Baghdad, and only a fool would miss the simple temptation for someone with that much power, that much land, to march to take Egypt from Gabriel and Konstantinopolis from von Franken…

“We all pray for an heir,” Skleros’ smile held solid and firm as a glacier. “My master, as well as Emperor Thomas, both pray daily for the safe delivery of your unborn child.”

“Thank you for your kindness,” Alexios tried to put on a pleasant smile. He knew he probably failed. “We too pray, for a son to be an heir to myself, my father, and Emperor Nikephoros.”

“Ah yes,” Skleros bared his fangs in a smile. “But Majesty, back to the business at hand,” he said pleasantly enough, “I will be requiring accommodations for two weeks while I finish my observations and write my reports for Konstantinopolis. From what I’ve seen, you are accomplishing much here in the war effort.”

Alexios’ heart leapt to his throat. The snake was staying two weeks?

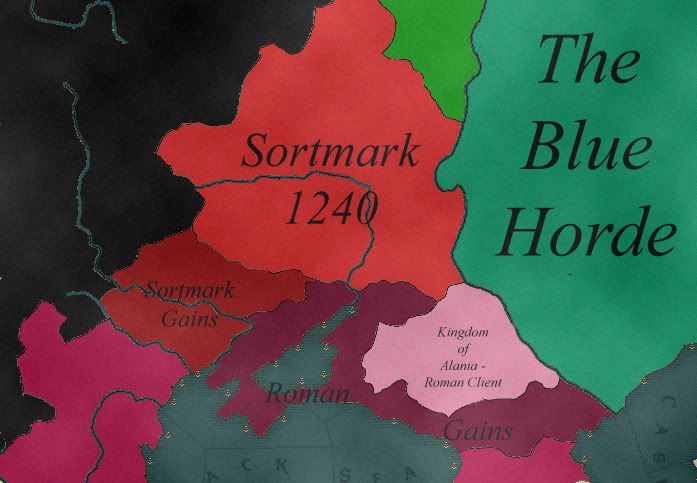

“Almost as much as King Knud accomplished last summer when he threw off the Mongol yoke,” Skleros went on. Skleros’ master had spent four years engineering a coup across the Black Sea. First, von Franken had bribed/cajoled/pushed the sons of the Danish Grand Duke into counseling their father into declaring himself King and formally divesting himself of his Mongol overlords. Then, once the Blue Horde panicked (for most of its forces were with Hulagu, on the orders of the Great Khan in Karakorum), von Franken offered Batu Khan a deal—Romanion would not support the Danes militarily, if the Romans were allowed to retake their lost TransPontic lands. The Romans, with a partial tagma and 10,000 thematakoi forcibly annexed the “Grand Principality of Cherson,” in 1246, while the Danes thumped the remaining tumen of Batu Khan at Cherniye Ozero, then promptly celebrated by seizing the lands of the former “Prince of Pereslavyl,” including the remains of their once magnificent capital at Havigraes. Reportedly the Emperor in Konstantinopolis sent the Danish King a gift of 4 tons of marble and 100 tons of granite, to make sure his palace was built of stone this time.

The plan had gone splendidly for all parties involved, save the Blue Horde.

“I thank Your Lordship for your kindness,” Alexios murmured, suddenly feeling naked and vulnerable despite his armor, title, and the army of men currently surrounding them. “Um...my stewards shall find suitable accommodation for you.”

“Thank you. I think,” Skleros added, turning his horse back towards the gates of the city, “I shall leave Your Majesty to the business at hand while I begin writing my reports and conduct some more tours of your camps. There is certainly no rest for the wicked, is there?” That smile somehow grew larger. “Good day, Your Majesty,” he bowed slightly to Alexios, before turning to Anastasia. “Majesty.”

==========*==========

So we’ve moved along quite a bit. Gabriel and the Mongols are at an impasse, while Nikephoros and Adrianos’ deal is now known—a marriage that could rock the political foundations of Romanion…

Looks like Eleutherios is the new Mehtar-type villain while Albrecht is more of a Nikolaios-turned Manuel, in that he used to be at least slightly averse to the blacker arts of statecraft, but has now become rather villainous himself, in his own way. Hopefully Alexios and Anastasia can thwart the snake's evil plots, but I somehow doubt it. Very unfortunate, because I think he's my new third favorite character, but I'm pretty sure his baby is going to die. As well as his wife. I think they'd leave him there since he seems like he would be rather easy to manipulate without his wife. Not that he's an idiot, but he just doesn't have the spine to deal with Albrecht and his evil henchman.

Looks like the Mongols are collapsing

I hope Alexios' wife an unborn child don't get murdered.

It also looks like Persia has become the greatest 'March' on earth.

Anyway no matter what happens I expect another Civil War very soon.

I hope Alexios' wife an unborn child don't get murdered.

It also looks like Persia has become the greatest 'March' on earth.

Anyway no matter what happens I expect another Civil War very soon.

Another rare competent Komnenid? That makes three at the moment, a new record!

I wouldn't call Albrecht a villain. He's more a 'the end justifies the means'-kind of guy who fears Gabriel will destroy the empire by waging impossible wars.

I wouldn't call Albrecht a villain. He's more a 'the end justifies the means'-kind of guy who fears Gabriel will destroy the empire by waging impossible wars.

Mongols bleeding themselves out - somewhat expected.

Jochi's get still listening to the Great Khan - not so much.

The mega-inheritance - yeah, that's special.

Jochi's get still listening to the Great Khan - not so much.

The mega-inheritance - yeah, that's special.

Mega inheritance? A child of Gabriel and Altani. Now THAT would be a mega inheritance.

It's strange Nikephoros hasn't sired any children yet. He didn't find an aprioppriate bride?

EDIT : Forgot about something. Don't you dare kill Nikephoros without any heirs!

It's strange Nikephoros hasn't sired any children yet. He didn't find an aprioppriate bride?

EDIT : Forgot about something. Don't you dare kill Nikephoros without any heirs!

Last edited:

Mega inheritance? A child of Gabriel and Altani. Now THAT would be a mega inheritance.

It's strange Nikephoros hasn't sired any children yet. He didn't find an aprioppriate birde?

Well, knowing Gabriel fucks everything that moves, that wouldn't be much surprising.

That mega-inheritance of Alexios' probable son would be a great setup for future civil wars of course, but I'd hope they stop the infighting for a while. Why are they never satisfied with what they have?

I can see this very easily going the way of the Megas where his one true (and very smart) love dies and he is left to rule an empire.

Well, knowing Gabriel fucks everything that moves, that wouldn't be much surprising.

:rofl:

Nice, I like all of these "side" characters they are very endearing

so all I can say is armonistan is

I wouldn't call Albrecht a villain. He's more a 'the end justifies the means'-kind of guy who fears Gabriel will destroy the empire by waging impossible wars.

I don't see the difference between this and Manuel's philosophy of Imperium uber alles, so to speak.. And I wouldn't call Manuel a holy man, by any means.

I wouldn't call Albrecht a villain. He's more a 'the end justifies the means'-kind of guy who fears Gabriel will destroy the empire by waging impossible wars.

So basically he is evil, just not eeeeviiiiil, like some, ie. Skleros.