Hey everyone!

Qorten - I tried my best... CK also tried its best to muddle things as much as possible!

Enewald - Possibly. Maybe. Considering the convoluted mess that's Russia, it could be a philosophical question with realistic underpinnings. (I don't know XD)

English Patriot - I've set the bar, now it's time for you to meet it. Go forth and tell us what happens with Silvangenus!

asd21593

asd21593 - Almost done with them!

AlexanderPrimus - Well, you won't have to wait much longer!

So, we've reached the end of the string of interim updates, and like I promised, I have a surprise for you all--two surprises, actually. The first relates to a question I asked everyone a long time ago (sometime just after Neapolis, I believe), about who the readers of this story thought should get their own musical theme. Overwhelmingly, Manuel won, followed by Demetrios, Mehtar and Thomas I. Unfortunately, Manuel fans, I do not have his theme finished yet, but I

did finish themes for Demetrios

Megas, and his great-grandson Thomas I (I will give a half brownie to who can tell me what songs were sampled in the themes.

)

Everyone let me know what you think of them!

Secondly, you all are in for a special treat! As you probably know, Calipah, a longtime reader, has been providing a great deal of insight, wonderful information, and invaluable help to me while writing the lead-up to the conquest of Mecca. If you found this portion of the story in depth and engaging, you need to give him a round of applause--without his help, and his nudging me towards the correct details (and the details make the depth!), I doubt the recently finished story arc would be half as good as it was.

About two or three months ago, I asked Calipah if he'd be interested in writing a little post detailing what would happen to this new 'Despotes' of Arabia, considering he's originally from Jeddah (the

capital of this mythical kingdom

) and his great knowledge. He leapt at the challenge, and what follows is a result of his brilliant ideas and a daring, unconventional look what would could result from this topsy-turvy political situation the Komnenoi have managed to create. So, without further ado, I present to you Dr. al-Jedawi's paper presentation on the Kingdom of Arabia, from 2007!

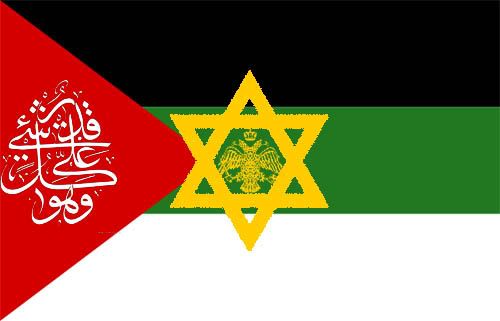

Flag of the United Pan-Arab Republic

Neo-Islam & Innovation: The Dilemma of Traditionalism in the Arab World

Imam Adronikon University, Al-Iskanderiiya, Al-Jumhuriiya al-Arabiyya al-Mutahida (United Pan-Arab Republic)

Distinguished Panel

Prof. Mohammedorn Al-Jedawi: Christian Arabia: Pandora’s Box in the Holy Lands – The History of the Dounari Hedjaz. (American University of Beirut, Faculty of History)

Prof. Amira Al-Sanbuli: The Sacred Feminine: The Role of Fatima Al-Zahra and Our Lady Mary as Revolutionary Symbols in the Sa’far Uprising – Ethos of the Founding Republic. (Imperial University of Kuwait)

Prof. Midhat Al-Heliopoli: The Memoirs of Sheik Ahmed al-Islamboli: The Reaction of the Egyptian falahin to the Aeoni-Islamic Reformation – Medieval Narratives. (Dau Institute of Historical Studies)

Prof. Alexios Al-Basrawi: Crown, Scepter, and Elite Cartels: The Nahdawi Republic in the backdrop of the Abbasid Royal Project – The Turbulent Decades of the 20th century. (Baghdad University, Al-Ghazali Chair)

Prof. David Rahbar: The beautiful Greek Pueri: Subaltern Sexuality in the Near East and the Imperial male-erotic construct. (Konstantinopolis, Faculty of Sexuality, Foucault Chair)

Prof. Sarah McKenzie: The Music and Poetry of Ibn Al-Arabi: Sufist Encounters from Konstantinopolis to Cordopolis in the 13th and 14th centuries. (Stanford University, School of Mudejarico Muslims)

Prof. Harun Zaikov: The Grand transformation of Aegyptus: House of Dau from Orthodox Romans to Aeonite Sultans – Symbols and Regalia from the Fatamid and Ptolemic Past. (Al-Azhar University, Faculty of History)

Transcript

Prof. Al-Jedawi: Thank you Professor Zoë for that wonderful, if somewhat exaggerated introduction! *crowd laughs* It is of great honor for myself to partake in this most prestigious and renowned forum. To add, if in a rather small and humble way to the great reservoir of knowledge it has already nurtured and preserved in these trying times is no little badge of praise one can wear lightly. No one can dispute the value of the academic research and debate the University of Adronikon has fostered, and especially in its contributions towards greater ecumenical solidarity within the Muslim community of the Republic. Furthermore, to be able to come here and participate in this lofty endeavor of understanding and tolerance amongst a brotherhood of the most exemplary of scholars is credit enough to this ancient institution’s aim to cement the growing network of academic camaraderie and spirit de corps across the commonwealth’s far-flung provinces. This is raw and naked good of the highest caliber. It is thus, I adjoin, of paramount consequence that this podium remain unyielding to the pressures of religious zealots and political cretins. We are neither totalitarian fascists playing to the harp of Greco-Slavic racial superiority on a fallout ridden wasteland nor Soghdiyan Communists constrained by Lavian dialectics! No, ladies and gentlemen, we are proud Pan-Arab Republicans firmly grounded on the principles of prudent Hellenese demokratia and Aeonite compassion!” *Long Applause*

“Thank you, thank you all. With my indignant Republican-drivel exhausted in its laurels *crowd laughs* I would like to turn to the subject of my work, namely, the Hedjaz. My paper is more or less an attempt to examine societal, cultural, and political reactions within the traditional Muslim Holy lands to the Dounari imposition. This is not to be taken as an effort to tackle the supra-continental reverberations of the Romani conquest on the Muslim World at large, for a great deal has been written on that topic already. Rather, I am more concerned with micro developments within the vicinity of the Hedjaz proper, and the periphery to an extent in the Najd, Najran, and Yemen. Several concerns were raised, and I would like to quell them by saying that I did not adhere to the Cornelian school of historiography in my research as I felt that whilst a Christian interregnum in the political structure of the area was indeed original and unprecedented, it could not be easily explained outside the context of continuity that links the traditional Muslim and later Aeonite periods, as well as concomitantly taking into account Romanion experiences with Muslim majority areas prior to the conquest. The Dounari, or perhaps more aptly Emperor Thomas – and I say this without remorse or hesitation – is integral to any true and honest understanding of the modern Arab cultural fabric in the Hedjaz and elsewhere. When I think about it, in an ironic way, he, more than any other, is due thanks to the Nahda and subsequent Tanweer that has swept the region in the early 19th century, but I’m getting ahead of myself and perhaps unwittingly trudging on Prof. Zaikov’s area of expertise. All in all, the Christian Hedjaz is part of our heritage, and by acknowledging it as such, we salvage a great deal of collective memory from the brink of oblivion or worse yet, from assigning it the fate of becoming mere fodder fanning the flames of religious fanaticism and discord.

So then, picking apart the dilemma of a Christian dynasty ruling over Mecca and Medina is of great significance in our undertaking of not only understanding the kernel and spirit of the Aeonite, Taymmite, Jawhari, or even Andalusi rite reformations, but bringing to the forefront the existential obliteration of traditional Islam. What I mean to say is that the Islam we practice today is literally and in every way different to pre-1238 Islam, and the point of disjunction lies with the capture of Mecca. I do hate watersheds myself as it constrains the interpretation of historical development to linear trajectories, but this one is inescapable. Whilst we retain the doctrine and outward ritual, a new set of institutions – both political and spiritual – were required in light of grievous eschatological failures at the onset of the Romani occupation. After all, the ‘Holy city’ was supposed to be inviolate till the Day of Judgment to take a common example from the contemporary theological tracts of the day. Critical analysis of the Quran and other religious texts begins from that point onwards really. Perhaps one could argue that the Mali Boku Islam or the Azmadi Islam of the Malay are exceptions here, but in fact, they corroborate my point, for none of them follow the stipulations of the old schools of Sunni jurisprudence. All this in the end mounts to the troublesome question of whether Muslims have lost the ‘divine-mandate’ or not. Quintessentially, does failure stem from Godly displeasure with the Ummah alone? Or is it a sign of Islam’s failure on both the material and spiritual planes? Muslims of course continued, in different syncretic ways, to adhere to the beliefs of their forefathers.

This is a natural and anthropologically-sound response of a community wrapped in a ‘besieged’ mentality. However, the occupation of the ‘Imperial’ Islamic core if you will, changed Islam’s nature invariably. As I said, a new discourse emerged – unlike any other before it – in which the Sultan and secular wings of the generic Muslim community were disbanded to make way for a new reality: How to be a Muslim under defacto and dejure non-Muslim rule. It’s quite fascinating really, for before the Fifth Empire and the Seljuk apogee, the traditional response of the Ulema and clerical classes had been to encourage a ‘Hijra’ in a formulaic imitation of the Prophet Mohammed *Peace be Upon Him* when he left Pagan Mecca to the safety of the then small town of Yathrib, now known also as Medinapolis al-Nur al-Muhmmadi. According to population censuses and records conducted by the Romanion Bureaucracy before the onset of the 13th century civil war however, very few Muslims ever actually left the Western or Eastern halves of the Empire for Muslim controlled territory, where supposedly the ideal Islam was practiced. Fundamentally, all of what was then known as the ‘Islamic World’ straddling the Mediterranean had been conquered, so hypothetically, Rumi rule was the only alternative available for most, barring the aristocracy and merchant castes. This brought about multiple outcomes I believe: First, a synergy or ‘mulahama’ transpired between the old Arab elite – and especially its Christian elements – with the newly inaugurated Greek nobility. Secondly, a process of demographic homogenization whereby Muslim peasants and urban dwellers congregated in or around specific major cities such as Halab or Baghdad as part of a minority-majority dynamic, and lastly, it galvanized efforts to either institutionalize Islam within the Empire or, if that recourse failed, to seek a proper mix of Gnostic Islam and Christianity so that, whilst the forms are shattered, the core ‘lub’ as the Sufi poet Makzumi would like to say, is preserved. I don’t mean to imply that these were all conscious and intentional developments, or that they occurred in the said succession and order. Far from it, but that they were byproducts of a highly confused and at times surreal Roman reconquest in the 12th century that shattered any illusions of Islamic preponderance in the Middle East.

I can see that Prof. Zoë is glaring at me harshly for my long and arduous detour, and I do apologize profusely, but one has to throw preliminary thoughts, no? *crowd laughs* So where to begin? The geographic entity known as ‘Hedjaz’ has never been truly defined; at times the whole western coast of the Arabian Peninsula, from Tabuk to Assir, had been designated with that name. At others, it had been constrained to the area of Mecca and Medina, including the towns of Jeddah and Taif in a sort of ‘sacred’ precinct. For our purposes, we will subscribe to the latter definition. Now the Hedjaz, as the cradle of the original Islamic movement, had always enjoyed prominent status in the spiritual consciousness of the Arab people. Before Islam, it was the prime Pagan site, the divine nexus where all the 365 gods of the clans were worshipped in a ritual very similar to Assyrian traditions, though the Kaabah was always a distinct and peculiar focus of worship through the primordial Hajj. After the return of the Prophet Mohammed in 630 to Mecca it was rechristened into an ‘Islamic’ holy site, where an ‘Arab’ prophet spoke an ‘Arabic’ Quran. The whole process has a tinge of proto-nationalism perhaps, but nonetheless it expresses an ethno-centric assertion in face of the traditional Semitic story whereby God’s words are always heard in Canaan, in Mesopotamia, in Sinai. With Islam, the story shifts southward, and the Arabs for the first time become the protagonists, in their eyes at least, of a holy and miraculous chapter in the prophetic narrative. In some respects, one could see an analogous reaction demonstrated by the Goths and Germanic tribes in their appropriation of ‘Roman’ heritage – at least in the West – as a way of placing themselves in the center of ‘Latin civilization.’ That’s one interpretation anyway whereby the margin is pulled to the core by centripetal force. Soft power at its best, ladies and gentlemen, except it’s on reverse! *a hesitant splatter of laughter from the crowd*

Politically, the Hedjaz had always been rather important, and more so during the early years of Islam. Increasingly however, and especially so after the great conquests of the 7th century, the Hedjaz, whilst being relegated heightened religious status due to the expansion of the Muslim patrimony and flock, was losing its significance as an administrative center. It was apparent that any aspirant to the throne should look towards Kufah, Basrah, Kairowan or even Merv and Fustat – the Arab city-cum-military complexes. It was obvious that simply because you enjoyed the support of the Meccan or Medinan nobility did not necessarily mean you were destined to the helm of leadership in the Muslim community – well, I suppose the Qurayish still had some strings to pull as we have seen with the rise of the Ummayeds, but that’s another story. This peculiar situation expresses itself aptly in hindsight: since the Rightly Guided Caliphal period and the early war-phase between the Fourth Caliph Ali bin Abi Talib and the Ummayed potentate and usurper Muwayiah, the capital was summarily and quietly may I add moved from Medina to the more central and accessible city of Kufah. The allure of ruling from the Prophet’s pulpit gave way to strategic, military, and political considerations, and there was simply no way around it the reality of Empire demanded it. Thus, the successor Muslim states were more concerned with securing wealthier territories such as Iraq, Syria or Egypt than the Hedjaz itself, though they did take the effort to include the holy cities in their spheres of influence as a means of garnering prestige in the eyes of the faithful. Yet I must emphasize the following: An empire is an empire irrespective of sacerdotal perceptions, and it is a well known fact that the Ummayeds laid siege to Mecca and catapulted the Kabaah during the Alawi revolts, sparing neither pilgrim nor rebel in their onslaught. Expectedly, and due to the peculiar nature of the region within the political machinations of Islam’s ‘great leaders,’ the Hedjaz found itself ruled by the ‘Sharifs’ or the Sayyid’s of the Prophet’s House. A comfortable and practical arrangement if any. Hand in hand with the merchants or ‘Tujjar,’ the Hashemites paid allegiance to whomever was in the neighborhood, endowing their new titular rulers – Abbasid, Seljuk, Fatimid or what have you - with a garb of religious legitimacy as needed. Well, as long as the tolls kept flowing in.

Now the Byzantines entered the Hedjaz following the defeat of the Seljuks in the last offensive led by the ailing Hajji Sultan Ferdows, who managed, for a short while at least, to rein in the rebellions of the Shiite Nizaris in Mashad and the Najjarites in Basrah, and draw strength for one last desperate attempt to retake the breadth of the Muslim east back in the dying calls of a muted Jihad. Then the Mongols came. Of course, the Sherif of Mecca, driven more by blind passion and the tantalizing prize of another Yarmuk on the plains of Madaba, abandoned common sense and joined the fray. In 1237, Emperor Thomas, after soundly crushing the Great Seljuk outside the Ahwaz, penetrated the Hedjaz and captured Medina. The road to Mecca was comparatively more difficult and long, though the shock of losing the Prophet’s shrine too great a psychological shock I fathom on the defenders. The stiff resistance displayed by the Bedouin tribes and the Zayidi Sultan in the Tuhama derailed the capture of Mecca for another year, but Romanion proved ever more resilient. On Ramadan the 17th, Romanion’s banner stood triumphant over the Fort of Zayen al-Abedeen overlooking the ancient Kabaah and its supplicants. In spite of this “disaster” however, I feel that most Muslims, as can be surmised from records and memoirs of the era and later on, were even more surprised that the Emperor, long known for his reign of bloodshed and terror against the nobility, displayed far great magnanimity and tolerance than any other monarch of that age and time. Perhaps there is some truth to the ‘legends and myths’ of a crypto-Muslim Thomas, or the ‘Specter of Mohammed’ but then again, it could simply be the projected desires of a Muslim population both grateful and spiteful towards the Komenid dynasty, and especially towards the Autokrator Gabriel. Given that he entered the Hedjaz proper with strictly Muslim troopa speaks volumes in and of itself. In the end, Emperor Thomas’s political acumen stemmed from a dual realization that the Empire still had a large Muslim population to deal with, and that this community by and large – putting aside the Mesopotamian episode -supported him in his efforts to retake the throne from the pretender and despot, the much hated Andreas Kaukadenos.

In 1238, in a rather unremarkable Imperial edict, Arabia, the heart of traditional Islamic faith, was bequeathed to Georgios Donauri, commander of the Basilikon Toxotai and lifelong friend of the Emperor,at first as 'Despotes,' and then in 1241, as outright 'King.' What is surprising in all this is that unlike the Byzantine handling of the Shiite Shrines in southern Iraq, where de jure ‘Christian’ overlordship was never asserted or proclaimed, the Hedjaz was indeed a far cry from expected Byzantine behavior. But here’s the catch: Georgios was a former Prince of the Outrejordain, and was, by virtue of many years of pragmatic rule, highly popular amongst the Muslims, both Bedouin and Hadari alike. Though it is likely we are merely encountering yet another batch of royal propaganda, the reception he received by the Ashraf, the Tujjar, and other elite in cosmopolitan Jeddah suggests otherwise. Whilst the ceremony of his Kingship over Arabia – a realm extending from the mountain town of Taif to include much of the Jordan – was not received with outright celebration or joy, it was nevertheless relatively peaceful than what one would expect. He, Georgios, made a point to never enter the Sacred area, and established his seat outside of Jeddah so as to not incite the indignation of Muslim pilgrims flowing into the Port city. Continuing local traditions, customs and laws, he was in some respects more severe than contemporary Muslim rulers in enforcing the Shariah, making sure he consulted with the four madhab jurisprudents in matters pertaining to local cases brought to court. Yet for all his forbearance, he was in the end a ‘Christian’ monarch, and his construction of a small chapel adjoining the stoic complex of ‘Qasr al-Daynori’ which incidentally hosts today the National Museum of this fine Republic was an avowal on his part to dismiss growing suspicions of ‘conversion’ tallied and proffered by jealous and covetous nobles egged on by a worried patriarchy in the capital. Yet all in all, the Hajj continued unabated, tolls collected, and caravansaries maintained. It’s actually ironic in a way that the number of pilgrims increased under Georgious’s reign as a result of his vigilance in combating banditry, and the fact that the Hedjaz was now firmly an Imperial ‘province’ for all intents and purposes.

Perhaps I’m presenting too much of a benign picture of the Dounari House. Whilst many denizens of the Hedjaz willingly bowed their heads to a Christian shadow prince, many more were up in arms before Georgios arrived to Jeddah itself following the news of Mecca’s fall. A faction within the Hashemite house rose up in rebellion against the Romani almost immediately, as well as many urban residents and ulema who could not tolerate the idea of a Christian ruled Hedjaz. The tribes, emanating chiefly from the center of Arabia and in and around the holy cities joined the fray and plagued the Dounari dynasty well until the arrival of the Aeonites in the late 14th century. To corroborate my point, the successive riots or ‘Hajji’ uprisings, as can be discerned from a wide array of annals and texts, were apparently a common occurrence, and in fact, had a cyclical quality to them throughout the breadth of the Empire. I found little to suggest that traditional Muslims, cryptic Muslims, or Aeonite adherents who came to perform the pilgrimage perceived the question of infidel rule over the holy cities differently.

Moreover, one must not dismiss the emergence of many esoteric and millenarian factions and groups, which accounted for a totally different set of problems for the Dounari House and its Overlords. Yet given all these troubles, the Dounari could not have survived for so long without counterbalancing forces, which included, besides Kostantinopolis’s official support, the arrival of Christian immigrants and merchants who settled mostly in the Aligrikiyya district in Jeddah, the rise of a collaborative Muslim ruling class, and the creation of a fully Muslim tagmata – the first I believe in the breadth of the Empire. One must add to this exhaustive list the utility of ‘going native’ and this is especially pronounced in the adoption of Arab names – a practice one rarely sees with the Greek nobility – and the courting of the Sheriffs and Hashemites through appointments and at times, and this may come as a surprise, intermarriage. Indeed, like past Emirs and Sultans, some of the Dounari saw something to gain by claiming descent from the Prophet, but whether that proved politically astute or not, I leave to further inquiry.

I have spoken volumes of hopplecock up to this point and the question presses itself: what is the end result of my research? We have been conveniently taught that the Hedjazi interregnum is but one of many instances – and it is a grievous one depending on a person’s point of view – of the many excesses of a Christian Empire and its persecution of a religion that represents its theological antithesis. I argue in this paper, that the Hedjaz instead stands for a synthesis between the needs of the ruling class to remain ‘true’ to its cultural roots, and the demands of prudent and wise rule in dealing with the sacred precincts of a uniformly non-Christian and large minority scattered throughout Imperial dominions.

*Audience claps*

Professor Zoe: Thank you so much Prof. Al-Jedawi for your illuminating talk on a subject that has such tremendous consequence on all historical findings dealing with ‘Muhajirun’ history. Now we would like to open the floor for questions. Ahhh, lets see…

Here's your chance, AAR fans! Calipah's volunteered to let us 'pick' Dr. al-Jedawi's brain about this possible future for our brave new world. So go ahead, ask him questions, and let's brainstorm together!

they gave me greek in greek, i wanted greek in english.