Rome AARisen - a Byzantine AAR

- Thread starter General_BT

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

I'm telling you--there will be an architect-emperor in the very near future. Or a civil war. (Or both...)

I was on edge for the entire update, expecting that either Alfred or Mehtar was going to die. You've got me suspicious of any food at all, GeneralBT!

I'm hungry....

FOR MORE OF THIS GREAT AAR!!!!!!!!1!!!!!11!!!!!!!!!!!!111!!!!!!!!!1!!!11!!!!!!!!ONE!!!!!!!!!

(/cheesy joke)

FOR MORE OF THIS GREAT AAR!!!!!!!!1!!!!!11!!!!!!!!!!!!111!!!!!!!!!1!!!11!!!!!!!!ONE!!!!!!!!!

(/cheesy joke)

So there you have it! Who tried to kill Gabriel? Will the Crown Prince be safe in hiding? Will Albrecht and Mehtar discover who is at fault in time? More will be revealed on Rome AARisen!

Will Mehtar perfect his recipes? And will Albrect every try any of them?

Pretending the Crown Prince is dead will certainly draw out some of the trouble makers, but can they maintain the charade and will it cause more turmoil than it's worth.

I like Antemios, though I'm surprised at how farcical his reaction to Gabriel's poisoning is.

Shame about Alexios.

Shame about Alexios.

I like Antemios, though I'm surprised at how farcical his reaction to Gabriel's poisoning is.

Nah, he's just manic depressive.

Nah, he's just manic depressive.

I believe the medical term is "batsh*t insane."

I believe the medical term is "batsh*t insane."

Also known as Komnenos Syndrome.

Pretty funny how this apparent "illness" has managed to persist for so long, I mean, we can't blame them for inbreeding. Must be a very dominant gene skulking around.Also known as Komnenos Syndrome.

Antemios seems like the kind of guy you would not hesitate to remove from the list of people you will invite to your party. Suppose we could use someone like him too, all these popular successful rulers can get quite dull after a while. Antemios strotting in and ruining the whole thing would be quite a sight.

So Thomas won the civil war (I suspected as much) and is still insane (I suspected as much) has kind of spine shuddering children (I suspected as much) and what's a Byzantine update without some poison involved (XD)

Well, BT, I would just like to say, that it ate up countless delightful nights, and quite possibly 3 weeks, but I made it through this Magnum Opus of yours. What a thoroughly amazing work of art. I give you all the plaudits, kudos, props etc for this. You truly make the characters come alive. It's a talent I could only aspire to. I would also just like to offer the fact that you have, quite possibly, converted me to Byzanto-philism...I may just have to fire up my own CK Roman Empire

Cheers!

~Hawk

Cheers!

~Hawk

Hawkeye1489 - Thank you for the plaudits, and welcome to the end of the story! (until the next update) By chance, are you originally from Iowa? I only ask because I am too, and its rare to run into people from the Hawkeye State.

canonized - What makes Thomas the Youngest or Gabriel so spine-shuddering? Surely they aren't that frightening?

vanin - Hmm... well, Thomas I wasn't exactly popular, nor would I qualify him as successful... and I wouldn't say Nikolaios was popular either...

AlexanderPrimus - Not all the Komnenoi have been crazy... yet...

VILenin - He's not completely that insane... at least compared to his dad...

an Alan - Welcome to the thread! Eh, its Romanion... attempted assassinations are normal here.

TC Pilot - Yes... and Alexios is only 45.

Kirsch27 - I'm glad it meets your approval!

asd21593 - Maybe I should start handing out bad joke cookies... lol.

Lordling - So any time I mention food you think someone's going to die! Maybe I should have a strictly culinary update then!

Nikolai - Maybe...

Fulcrumvale - Knowing this family, the more chaos the better... what better than an architect emperor trying to build the Tower of Babel during a civil war?

RGB - Lots of people have tried, and no one has succeeded. Yet.

Qorten - I would, if I could cook...

Deamon - We've got one vote for Antemios, one for Thomas...

Enewald - There'll probably be more quotes coming from it shortly...

4th Dimension - Trust me, if little Nikephoros inherits, VERY interesting things will happen in the West...

In lieu of the next update (which hasn't been started yet thanks to a slew of job interviews and distractions), I've decided to post some basic information on the Spanish Empire as it stands in 1230 (and fill in some of the details people have been wanting to know)...

The “Western Empire,” officially the Roman Empire in the West, was a imperial unit initially built as an extension of the Eastern Emperor’s will, only acquiring it’s own independence during the chaos at the end of Thomas I’s reign in 1202. Even in 1230, the territory of the Empire is vastly Muslim in the south, with a Catholic north and an overlying nobility that is predominantly Greek and Orthodox sprinkled across the entire region. While normally one would expect the largely Muslim merchant and urban elites to clash with the Catholic martial peoples of the north and a Greek nobility, a rough truce has been formed between all three groups, under the auspices of a remarkable man—Alexios I Komnenos.

Alexios I Komnenos, ruler of the Western Empire since its declaration in 1202, has proven a wise and munificent leader at home, and a feared general and statesman abroad. Amongst the significant Muslim population in the south, Alexios is known as al-Malik al-Mua’zam, “the Glorious King.” The grandson of Emperor Basil III by his eldest son David, in the eyes of the Latin West Alexios also has the most legitimate claim to the Eastern Roman throne, a claim the Komnenos has so far refused to prosecute. At first, this was because of the haphazard hold he had on his own throne in Spain—now, 28 years later, it is more likely due to the simple problems of culture and logistics.

Logistically, taking Konstantinopolis and holding it, even during the midst of the Great Civil War, would have taxed even Alexios’ massive resources. For more importantly, by the 1210s, Alexios was already regarded by those in the old Empire as a ‘new’ monarch—someone not quite Roman enough to be a Roman Emperor. Part of this comes from the early stages of cultural fusion that began under his reign, part from his comparative (and arguably politically astute) toleration of Muslims and part from his promotion of Latin Catholics in his court.

Originally the Spanish Empire was a rough amalgamation of the five original exarchates created by Basil III: Lusitania, Baetica, Tarraconensis, Galicia and Mauretania. Alexios inherited Lusitania on the death of his uncle great-uncle Enguerrand, and after the demise of the Jimenez clan his interests also claimed most of Galicia, giving him the political clout to declare himself Emperor. To further cement his position, Alexios married the sister of Exarch Thrakesios in 1205, cementing together the futures of Baetica and his own Exarchates of Mauretania and Lusitania. Combined, these three Exarchates would form the future core of the Western Empire, allowing Alexios to dominate Spanish politics for decades to come.

The political structure of the Western Empire below the level of the exarchates varied immensely. To the north, in the former lands of Castile, Leon, Galicia and Aragon, underneath the exarchates a decidedly feudal system of government remained. The region was divided into themes officially, but in practice these units followed the borders of the ancient duchies and counties of the north, and just like their ancestors, their nobility retained their princely rights through families. Less populated and more militaristic, the Emperor in the West saw little reason to modify the existing power balance—he merely installed himself on top as the senior liege lord.

To the south, amongst the former Muslim taifas, the Roman imports had far better luck creating a system somewhat resembling the themata of the old Empire. The south of the Empire was parceled out to both Greek and loyal Muslim/convert nobility, who were granted titles of Prince and Strategos for their respective regions. These appointments were by Imperial seal and approval only—and as the Emperor’s power was seated in the south, any attempt to rebel or break from this system next door to His Imperial Majesty proved most unwise. The seven great cities of the south—Cordoba, Toledo, Seville, Fez, Basiliopolis, Granada and Cadiz—were granted special rights and privileges, as well as praetors who reported directly to the Emperor in Cordoba, not their respective exarch.

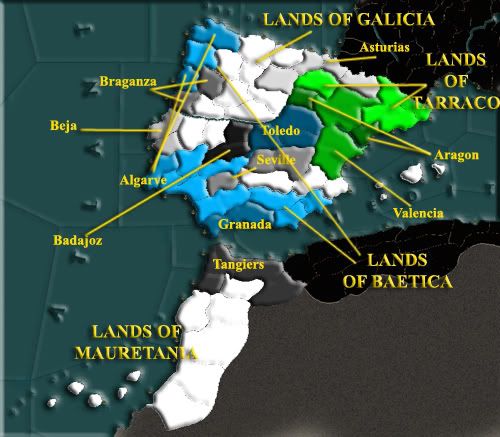

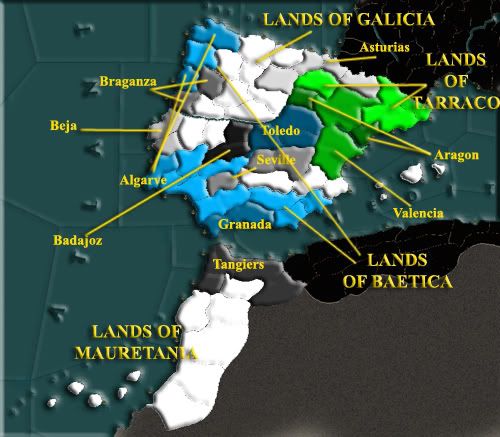

The politically chaotic map of the Spanish Empire. White are the areas held personally by the Emperor or his direct vassals. Shades of grey to black represent the great dukes and princes that are technically a part of the imperial exarchates. Tangiers, Beja, Braganza and Seville all operate as Greek thema, while Asturias functions as a Latin Duke with the Emperor as his liege lord. Blue represents Baetica, who has three underlings of repute—Granada and Toledo, both predominantly Muslim thema, and Algarve, which runs as a Latin dukedom. Finally, Tarraconensis is the least powerful. Both Aragon and Valenica function as Latin dukedoms, with Valenica arguably having the same power as the Exarch that is her nominal liege.

Also, unlike his eastern cousin, the Western Emperor also had a clear and secure line of successors. Alexios has three sons of his own—his son and heir Nikephoros, aged 28, Thomas, aged 22, and Basilieos, aged 18. All three have children of their own as well. While some dynastic rivalry exists, the lack of heirs for the Exarchate of Baetica likely means that Nikephoros will become Emperor, Thomas will become Baetian Exarch, while Basilieos will receive the rump of Lusitania and Galicia that isn’t under his brother’s control. Such an arrangement could prove tenuous.

The Western Empire is religiously and politically split into three camps. In the north, the less urban Catholic realms like the duchies and princedoms of Asturias, Aragon and Valenica, in the south, the more urban Muslim areas of southern Spain and northern Mauretania, and finally the nomadic far south, rich with Islamic heritage as well as even older traditions. All of these regions also have their own separate histories and cultures—the north is more a story of survival against odds, the few remaining Catholic states pushed and abutted by powerful Muslim neighbors. In the south, the story changes to one of imperial power—the Ummayads once had Cordoba as the largest city in Europe, and both Toledo and the Al-Murabatids built powerful empires only a century before. Overlaying all of this is the newest addition to the religious and cultural mix—a small but growing minority of Greek Orthodox, spearheaded by nobility appointed by Konstantinopolis and reinforced by émigrés and merchants from the old Empire.

Spain and North Africa are split clearly on religious lines—the north is Latin, the south is Muslim. Only in the Imperial capital of Cordoba has Orthodoxy made any significant headway.

To build and safeguard his shaky Hellenic crown, Alexios shrewdly set about propping up elements and symbols of an imperial legacy he knew his disparate subjects could understand. Firstly, he set about creating a truly imperial capital in Cordoba, rebuilding numerous Ummayad structures, as well as adding a massive new palace. Built on a promontory overlooking the city of Cordoba, the palace was part fortification, part fanciful—immense, imposing, yet when one reached the interior, brilliantly decorated in bright and vibrant colors.

The first Western Imperial palace, overlooking the city of Cordoba. Alexios’ residence was heavily influenced by Latin architects already present in the city for the alterations on the Grand Mosque.

The “Glorious King” has also made extensive efforts to borrow from Spain’s Imperial Ummayad past, a nod to his Muslim subjects, while retaining both a truly Hellenic outlook as well as elements of Latin Christianity. The Grand Mosque was converted into a Church, Alexios hired architects and craftsmen from Western Europe to change and modify the structure, building a splendid Gothic Cathedral in the heart of the Ummayad structure in honor of his grandfather, Hagios Basilieos. Meanwhile, the Emperor did not stop the Muslims of Cordoba from building a smaller, still architecturally stunning mosque of their own on the southern edge of the city.

A present day view of what was the Grand Mosque, now Hagios Basilieos Cathedral.

The new mosque constructed on the city outskirts was smaller, but no less brilliant in design.

This building campaign in Cordoba has been echoed in the other great cities of al-Andalus—Toledo received a new church and reinforced city walls, the commercial district of Seville was rebuilt, Barcelona’s harbor refined, and Valenica’s walls redone. In 1221, Alexios even commissioned the formation of a University in Cordoba, to echo similar insitutions of great learning found in Alexandria, Konstantinopolis, and northern Italy. For these rebuilding efforts, Alexios has received another nickname – the “Ummayad Roman.”

Further to the north, the Emperor used the vast resources at his disposal to embark on an epic campaign of castle-building. Between 1205 and 1229, Emperor Alexios built no fewer than 36 castles from Asturias and Galicia to Valenica. Many of these were modest, with curtain walls, a keep, and no more, but they were strategically placed at choke points or heights overlooking important roads. In effect, even while the northern nobility was allowed to exercise its feudal privileges on paper, by 1229 exercising them in fact and going against the Imperial will was simply ‘suicide by liege.’

Castillo de la Mota, one of the many fortresses built in the northern regions under the reign of Alexios I

Governing this mix of Muslim, Latin and Greek is no easy task, but it’s one that Alexios had taken to with aplomb. The Emperor maintains two separate councils, the Cortes Generales, a feudal assembly of nobles and merchants from the northern, Latin parts of his Empire, and the 'Shurat Ulayat Ahyl Al-Andalus li Muluk Ar-Rum fi Qurtubah' (‘Council of the High People of Al-Andalus to the Roman Kings of Cordoba'), known more simply as ’Shurat Ahyl Al-Andalus’. While the Cortes was filled with representatives of the great feudal north, as well as specific representatives of Barcelona and Valencia, the Shurat’s membership was based around the structure of the old taifas left from the fall of the Ummayad Caliphate, as well as the elders of some of the Almohad tribes from the far south. Both of these councils existed to advise the Emperor and his central council (made of mostly Greek elites) on affairs and relations with his disparate subjects.

Legally, the restrictions on religion were liberal for the time. Muslim and Jewish subjects of the crown were required to pay the Amaforos, or ‘heathen tax.” In return for this monetary ‘punitive’ payment, for the most part the Empire never pressed further. Latin subjects were urged to convert to True Orthodoxy, but little concerted government effort took place. However, through the natural processes of ambition and sincere thought, slowly a trickle of elites from the Latin, Muslim, and Jewish camps are converting as a route to higher station in the Eastern Orthodox government.

With this mix of liberal attitudes towards Islam and a focus on scholarly learning, Cordoba has become a center of the scholastic movement in both Christianity and Islam. With the patronage of the Western Emperor, scholars as varied as ibn Tufayl, ibn Khatib and al-Rindi have gathered from the Muslim world, while the likes of Dominic de Guzman and Albert of Cologne have come from the Christian world, both sides seeking Cordoba’s unparalleled access to ancient texts from Aristotle and other Greek philosophers of logic.

A statue to Averroes, which graces the present corridors of the University of Cordoba

This meeting of minds has given Cordoba’s court a dual reputation—one of unbridled brilliance, and also one of scandal. Alexios’ openness towards Muslim scholars especially has raised the ire of the Papacy in Hamburg, as well as the conservative Patriarch of Jerusalem. However, the Emperor’s personal popularity, coupled with the distant reach and hold those two forces have on Spanish politics, has granted him a measure of some immunity from their wrath—for now.

The Spain ruled by Alexios Komnenos was, apart from it’s religious divisions, a prosperous region. Christians and Moslems in both the north and the south had a long history of contact and cooperation in economic ventures—if anything, the union of the peninsula and North Africa cemented economic prosperity with the end of the abortive Reconquista and the various wars between the Christian states of the north and the Muslim states of the south. The spread of the great Toledan and Morocca kingdoms before Roman arrival in effect prepared the ground for eventual economic unification, stripping away the power of individual taifas and building a large communal economic zone. This calm at home as allowed for Andalusian and Spanish merchants, by 1229, to begin to take steps abroad. The Spanish Empire uses the solidus, just like its sister to the East. Tapping into this massive currency market means that merchants from Spain can effectively go anywhere in the Mediterranean and most of Europe—while the Latin kings might not speak Greek, Greek coin speaks volumes.

No empire can survive long without the sword, and the Western Empire was no different. Under Alexios, the Western Empire operates under a mixed system for its armies—northern areas rely upon a traditional feudal levy as well as feudal obligations for their contributions.

The military backbone of the Empire lay in the north, amongst the less urban and more warlike Christian areas. Alexios here set about rebuilding fortifications and castles in his personal domains, attempting to bolster up his power and control the errant local nobility.

Areas such as Galicia, Asturias, and Catalonia tend to provide troops that are heavily focused on Latin knights as the core of their fighting contingents, with assorted auxiliaries and levies as supplement and reinforcement.

Further to the south, where the Muslim city-states have long had a tradition of forming standing urban defensive units, many of the military units come from city contributions—Cordoba, for example, has a militia of 8,000 ready to serve the Emperor at one months’ notice. These militias, like those of Italian, are well trained and equipped, and provide a formidable force that is easily augmented into the few standing Western tagmata.

Finally, in true Roman fashion, the Western Emperor also has standing tagmata of his own—in this case, five cavalry tagmata intended to augment the militias of the south and the levies of the north. Two of these tagmata fit within the traditional Roman military system—the Imiselinos and Stavros are both standard Roman kavallaroi units. Added to this are two more light tagmata recruited mostly from North Africa, the Aetoi and Trykimia both are mounted on camels, lightly armed and armored, and are intended to function as skirmish troops or cavalry disruption.

The last of the Imperial tagmata is perhaps the most interesting. It’s name itself is something that symbolizes the new union going on in Spain—the Rigal al-Khilafah al-Masihiyya, or “Men of the Christian Caliphate.” These soldiers, by and large Muslim, form the personal bodyguard of the Western Emperor, much as the Hetaratoi have since the days of the Megas done the same for their Eastern counterparts. While capable of fighting as super-heavy cavalry like their eastern cousins, these units are also trained to operate as light archers as well, depending on the Emperor’s need and the conditions they operate in.

A representative line-up of the major components of the Western Imperial Army. On the far left is a commander of the Rigal al-Khilafah tagma in full dress armor. Next lies a member of one of the Greek kavallaroi tagmata in battle gear, followed by a Latin knight as one would find in the feudal armies of the northern lords. Fourth there is a member of one of the city militias as raised by the taifa in the south, and finally a lighter North Africa soldier, representative of the Mauretanian levies.

Altogether, should he go to war, the Spanish Emperor has the potential to muster a formidable force of over 150,000 soldiers. More realistically, considering the disparate nature of his realm, Emperor Alexios has placed 60,000 in the field in his largest campaign.

In the immediate future, so long as Alexios Komnenos remains on the Western throne, the future of the Empire seems secure. In the future after his death, so long as the Exarchsof Baetica remain basic extensions of the main imperial line, and an active mind rules the Empire, Spanish unity should remain strong, despite the internal pressures against it. However, should lax hands ever take the reins, it is likely the Empire would fly apart within a generation. North and South would likely pull away from each other, and dynastic rivalries amongst the Greek elites would quickly use these divisions to bring troops into the field.

Unfortunately, it does not look as if Alexios’ son Nikephoros can provide the leadership the Empire will need. He is neither indolent nor lazy, but he simply lacks his father’s brilliance in dealing with multiple worlds and cultures. His son, also named Nikephoros, could be a bright hope further down the line, but he is only a child…

canonized - What makes Thomas the Youngest or Gabriel so spine-shuddering? Surely they aren't that frightening?

vanin - Hmm... well, Thomas I wasn't exactly popular, nor would I qualify him as successful... and I wouldn't say Nikolaios was popular either...

AlexanderPrimus - Not all the Komnenoi have been crazy... yet...

VILenin - He's not completely that insane... at least compared to his dad...

an Alan - Welcome to the thread! Eh, its Romanion... attempted assassinations are normal here.

TC Pilot - Yes... and Alexios is only 45.

Kirsch27 - I'm glad it meets your approval!

asd21593 - Maybe I should start handing out bad joke cookies... lol.

Lordling - So any time I mention food you think someone's going to die! Maybe I should have a strictly culinary update then!

Nikolai - Maybe...

Fulcrumvale - Knowing this family, the more chaos the better... what better than an architect emperor trying to build the Tower of Babel during a civil war?

RGB - Lots of people have tried, and no one has succeeded. Yet.

Qorten - I would, if I could cook...

Deamon - We've got one vote for Antemios, one for Thomas...

Enewald - There'll probably be more quotes coming from it shortly...

4th Dimension - Trust me, if little Nikephoros inherits, VERY interesting things will happen in the West...

In lieu of the next update (which hasn't been started yet thanks to a slew of job interviews and distractions), I've decided to post some basic information on the Spanish Empire as it stands in 1230 (and fill in some of the details people have been wanting to know)...

Ruler & Politics:

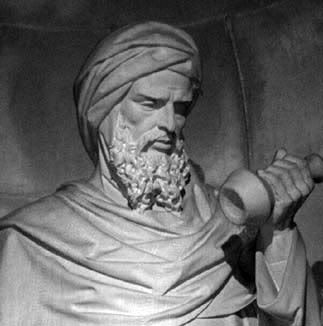

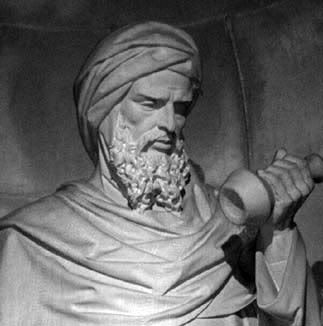

Alexios Komnenos as a younger man. By 1229, the Emperor would have been 45

Alexios Komnenos as a younger man. By 1229, the Emperor would have been 45

Alexios I Komnenos, ruler of the Western Empire since its declaration in 1202, has proven a wise and munificent leader at home, and a feared general and statesman abroad. Amongst the significant Muslim population in the south, Alexios is known as al-Malik al-Mua’zam, “the Glorious King.” The grandson of Emperor Basil III by his eldest son David, in the eyes of the Latin West Alexios also has the most legitimate claim to the Eastern Roman throne, a claim the Komnenos has so far refused to prosecute. At first, this was because of the haphazard hold he had on his own throne in Spain—now, 28 years later, it is more likely due to the simple problems of culture and logistics.

Logistically, taking Konstantinopolis and holding it, even during the midst of the Great Civil War, would have taxed even Alexios’ massive resources. For more importantly, by the 1210s, Alexios was already regarded by those in the old Empire as a ‘new’ monarch—someone not quite Roman enough to be a Roman Emperor. Part of this comes from the early stages of cultural fusion that began under his reign, part from his comparative (and arguably politically astute) toleration of Muslims and part from his promotion of Latin Catholics in his court.

Originally the Spanish Empire was a rough amalgamation of the five original exarchates created by Basil III: Lusitania, Baetica, Tarraconensis, Galicia and Mauretania. Alexios inherited Lusitania on the death of his uncle great-uncle Enguerrand, and after the demise of the Jimenez clan his interests also claimed most of Galicia, giving him the political clout to declare himself Emperor. To further cement his position, Alexios married the sister of Exarch Thrakesios in 1205, cementing together the futures of Baetica and his own Exarchates of Mauretania and Lusitania. Combined, these three Exarchates would form the future core of the Western Empire, allowing Alexios to dominate Spanish politics for decades to come.

The political structure of the Western Empire below the level of the exarchates varied immensely. To the north, in the former lands of Castile, Leon, Galicia and Aragon, underneath the exarchates a decidedly feudal system of government remained. The region was divided into themes officially, but in practice these units followed the borders of the ancient duchies and counties of the north, and just like their ancestors, their nobility retained their princely rights through families. Less populated and more militaristic, the Emperor in the West saw little reason to modify the existing power balance—he merely installed himself on top as the senior liege lord.

To the south, amongst the former Muslim taifas, the Roman imports had far better luck creating a system somewhat resembling the themata of the old Empire. The south of the Empire was parceled out to both Greek and loyal Muslim/convert nobility, who were granted titles of Prince and Strategos for their respective regions. These appointments were by Imperial seal and approval only—and as the Emperor’s power was seated in the south, any attempt to rebel or break from this system next door to His Imperial Majesty proved most unwise. The seven great cities of the south—Cordoba, Toledo, Seville, Fez, Basiliopolis, Granada and Cadiz—were granted special rights and privileges, as well as praetors who reported directly to the Emperor in Cordoba, not their respective exarch.

The politically chaotic map of the Spanish Empire. White are the areas held personally by the Emperor or his direct vassals. Shades of grey to black represent the great dukes and princes that are technically a part of the imperial exarchates. Tangiers, Beja, Braganza and Seville all operate as Greek thema, while Asturias functions as a Latin Duke with the Emperor as his liege lord. Blue represents Baetica, who has three underlings of repute—Granada and Toledo, both predominantly Muslim thema, and Algarve, which runs as a Latin dukedom. Finally, Tarraconensis is the least powerful. Both Aragon and Valenica function as Latin dukedoms, with Valenica arguably having the same power as the Exarch that is her nominal liege.

Also, unlike his eastern cousin, the Western Emperor also had a clear and secure line of successors. Alexios has three sons of his own—his son and heir Nikephoros, aged 28, Thomas, aged 22, and Basilieos, aged 18. All three have children of their own as well. While some dynastic rivalry exists, the lack of heirs for the Exarchate of Baetica likely means that Nikephoros will become Emperor, Thomas will become Baetian Exarch, while Basilieos will receive the rump of Lusitania and Galicia that isn’t under his brother’s control. Such an arrangement could prove tenuous.

Religion & Culture

The Western Empire is religiously and politically split into three camps. In the north, the less urban Catholic realms like the duchies and princedoms of Asturias, Aragon and Valenica, in the south, the more urban Muslim areas of southern Spain and northern Mauretania, and finally the nomadic far south, rich with Islamic heritage as well as even older traditions. All of these regions also have their own separate histories and cultures—the north is more a story of survival against odds, the few remaining Catholic states pushed and abutted by powerful Muslim neighbors. In the south, the story changes to one of imperial power—the Ummayads once had Cordoba as the largest city in Europe, and both Toledo and the Al-Murabatids built powerful empires only a century before. Overlaying all of this is the newest addition to the religious and cultural mix—a small but growing minority of Greek Orthodox, spearheaded by nobility appointed by Konstantinopolis and reinforced by émigrés and merchants from the old Empire.

Spain and North Africa are split clearly on religious lines—the north is Latin, the south is Muslim. Only in the Imperial capital of Cordoba has Orthodoxy made any significant headway.

To build and safeguard his shaky Hellenic crown, Alexios shrewdly set about propping up elements and symbols of an imperial legacy he knew his disparate subjects could understand. Firstly, he set about creating a truly imperial capital in Cordoba, rebuilding numerous Ummayad structures, as well as adding a massive new palace. Built on a promontory overlooking the city of Cordoba, the palace was part fortification, part fanciful—immense, imposing, yet when one reached the interior, brilliantly decorated in bright and vibrant colors.

The first Western Imperial palace, overlooking the city of Cordoba. Alexios’ residence was heavily influenced by Latin architects already present in the city for the alterations on the Grand Mosque.

The “Glorious King” has also made extensive efforts to borrow from Spain’s Imperial Ummayad past, a nod to his Muslim subjects, while retaining both a truly Hellenic outlook as well as elements of Latin Christianity. The Grand Mosque was converted into a Church, Alexios hired architects and craftsmen from Western Europe to change and modify the structure, building a splendid Gothic Cathedral in the heart of the Ummayad structure in honor of his grandfather, Hagios Basilieos. Meanwhile, the Emperor did not stop the Muslims of Cordoba from building a smaller, still architecturally stunning mosque of their own on the southern edge of the city.

A present day view of what was the Grand Mosque, now Hagios Basilieos Cathedral.

The new mosque constructed on the city outskirts was smaller, but no less brilliant in design.

This building campaign in Cordoba has been echoed in the other great cities of al-Andalus—Toledo received a new church and reinforced city walls, the commercial district of Seville was rebuilt, Barcelona’s harbor refined, and Valenica’s walls redone. In 1221, Alexios even commissioned the formation of a University in Cordoba, to echo similar insitutions of great learning found in Alexandria, Konstantinopolis, and northern Italy. For these rebuilding efforts, Alexios has received another nickname – the “Ummayad Roman.”

Further to the north, the Emperor used the vast resources at his disposal to embark on an epic campaign of castle-building. Between 1205 and 1229, Emperor Alexios built no fewer than 36 castles from Asturias and Galicia to Valenica. Many of these were modest, with curtain walls, a keep, and no more, but they were strategically placed at choke points or heights overlooking important roads. In effect, even while the northern nobility was allowed to exercise its feudal privileges on paper, by 1229 exercising them in fact and going against the Imperial will was simply ‘suicide by liege.’

Castillo de la Mota, one of the many fortresses built in the northern regions under the reign of Alexios I

Governing this mix of Muslim, Latin and Greek is no easy task, but it’s one that Alexios had taken to with aplomb. The Emperor maintains two separate councils, the Cortes Generales, a feudal assembly of nobles and merchants from the northern, Latin parts of his Empire, and the 'Shurat Ulayat Ahyl Al-Andalus li Muluk Ar-Rum fi Qurtubah' (‘Council of the High People of Al-Andalus to the Roman Kings of Cordoba'), known more simply as ’Shurat Ahyl Al-Andalus’. While the Cortes was filled with representatives of the great feudal north, as well as specific representatives of Barcelona and Valencia, the Shurat’s membership was based around the structure of the old taifas left from the fall of the Ummayad Caliphate, as well as the elders of some of the Almohad tribes from the far south. Both of these councils existed to advise the Emperor and his central council (made of mostly Greek elites) on affairs and relations with his disparate subjects.

Legally, the restrictions on religion were liberal for the time. Muslim and Jewish subjects of the crown were required to pay the Amaforos, or ‘heathen tax.” In return for this monetary ‘punitive’ payment, for the most part the Empire never pressed further. Latin subjects were urged to convert to True Orthodoxy, but little concerted government effort took place. However, through the natural processes of ambition and sincere thought, slowly a trickle of elites from the Latin, Muslim, and Jewish camps are converting as a route to higher station in the Eastern Orthodox government.

With this mix of liberal attitudes towards Islam and a focus on scholarly learning, Cordoba has become a center of the scholastic movement in both Christianity and Islam. With the patronage of the Western Emperor, scholars as varied as ibn Tufayl, ibn Khatib and al-Rindi have gathered from the Muslim world, while the likes of Dominic de Guzman and Albert of Cologne have come from the Christian world, both sides seeking Cordoba’s unparalleled access to ancient texts from Aristotle and other Greek philosophers of logic.

A statue to Averroes, which graces the present corridors of the University of Cordoba

This meeting of minds has given Cordoba’s court a dual reputation—one of unbridled brilliance, and also one of scandal. Alexios’ openness towards Muslim scholars especially has raised the ire of the Papacy in Hamburg, as well as the conservative Patriarch of Jerusalem. However, the Emperor’s personal popularity, coupled with the distant reach and hold those two forces have on Spanish politics, has granted him a measure of some immunity from their wrath—for now.

Economy:

The Spain ruled by Alexios Komnenos was, apart from it’s religious divisions, a prosperous region. Christians and Moslems in both the north and the south had a long history of contact and cooperation in economic ventures—if anything, the union of the peninsula and North Africa cemented economic prosperity with the end of the abortive Reconquista and the various wars between the Christian states of the north and the Muslim states of the south. The spread of the great Toledan and Morocca kingdoms before Roman arrival in effect prepared the ground for eventual economic unification, stripping away the power of individual taifas and building a large communal economic zone. This calm at home as allowed for Andalusian and Spanish merchants, by 1229, to begin to take steps abroad. The Spanish Empire uses the solidus, just like its sister to the East. Tapping into this massive currency market means that merchants from Spain can effectively go anywhere in the Mediterranean and most of Europe—while the Latin kings might not speak Greek, Greek coin speaks volumes.

Military:

No empire can survive long without the sword, and the Western Empire was no different. Under Alexios, the Western Empire operates under a mixed system for its armies—northern areas rely upon a traditional feudal levy as well as feudal obligations for their contributions.

The military backbone of the Empire lay in the north, amongst the less urban and more warlike Christian areas. Alexios here set about rebuilding fortifications and castles in his personal domains, attempting to bolster up his power and control the errant local nobility.

Areas such as Galicia, Asturias, and Catalonia tend to provide troops that are heavily focused on Latin knights as the core of their fighting contingents, with assorted auxiliaries and levies as supplement and reinforcement.

Further to the south, where the Muslim city-states have long had a tradition of forming standing urban defensive units, many of the military units come from city contributions—Cordoba, for example, has a militia of 8,000 ready to serve the Emperor at one months’ notice. These militias, like those of Italian, are well trained and equipped, and provide a formidable force that is easily augmented into the few standing Western tagmata.

Finally, in true Roman fashion, the Western Emperor also has standing tagmata of his own—in this case, five cavalry tagmata intended to augment the militias of the south and the levies of the north. Two of these tagmata fit within the traditional Roman military system—the Imiselinos and Stavros are both standard Roman kavallaroi units. Added to this are two more light tagmata recruited mostly from North Africa, the Aetoi and Trykimia both are mounted on camels, lightly armed and armored, and are intended to function as skirmish troops or cavalry disruption.

The last of the Imperial tagmata is perhaps the most interesting. It’s name itself is something that symbolizes the new union going on in Spain—the Rigal al-Khilafah al-Masihiyya, or “Men of the Christian Caliphate.” These soldiers, by and large Muslim, form the personal bodyguard of the Western Emperor, much as the Hetaratoi have since the days of the Megas done the same for their Eastern counterparts. While capable of fighting as super-heavy cavalry like their eastern cousins, these units are also trained to operate as light archers as well, depending on the Emperor’s need and the conditions they operate in.

A representative line-up of the major components of the Western Imperial Army. On the far left is a commander of the Rigal al-Khilafah tagma in full dress armor. Next lies a member of one of the Greek kavallaroi tagmata in battle gear, followed by a Latin knight as one would find in the feudal armies of the northern lords. Fourth there is a member of one of the city militias as raised by the taifa in the south, and finally a lighter North Africa soldier, representative of the Mauretanian levies.

Altogether, should he go to war, the Spanish Emperor has the potential to muster a formidable force of over 150,000 soldiers. More realistically, considering the disparate nature of his realm, Emperor Alexios has placed 60,000 in the field in his largest campaign.

Long Term Prospects:

In the immediate future, so long as Alexios Komnenos remains on the Western throne, the future of the Empire seems secure. In the future after his death, so long as the Exarchsof Baetica remain basic extensions of the main imperial line, and an active mind rules the Empire, Spanish unity should remain strong, despite the internal pressures against it. However, should lax hands ever take the reins, it is likely the Empire would fly apart within a generation. North and South would likely pull away from each other, and dynastic rivalries amongst the Greek elites would quickly use these divisions to bring troops into the field.

Unfortunately, it does not look as if Alexios’ son Nikephoros can provide the leadership the Empire will need. He is neither indolent nor lazy, but he simply lacks his father’s brilliance in dealing with multiple worlds and cultures. His son, also named Nikephoros, could be a bright hope further down the line, but he is only a child…

Last edited:

Intriguing stuff, BT.

It's fascinating to see how such disparate cultures can slowly be fused into an imperialist nation-state.

It's fascinating to see how such disparate cultures can slowly be fused into an imperialist nation-state.

Well...if the system works, perhaps brilliance is not required.

---

Excellent update, and suprisingly modest conversions to the True Faith. But time will tell

---

Excellent update, and suprisingly modest conversions to the True Faith. But time will tell

Boy, do I hope that Nike jr inherits. I wish the Western Empire to retain its dominance, it certainly would give interesting results on Europe's political history and development down the line...

...or not. The western Empire, for all of its immense potential, faces a severe risk of disintegration in the event of a prolonged period of weak leadership and/or civil war. The fact that there are three incipient branches of Kommnenoi in Spain does not inspire much confidence, nor does the fact that the heir apparent evidently does not live up to the promise of his father. In fact, I just had a rather evil idea: what if a Civil War leads to one claimant gaining a overwhelming support from the Christian north while the other utilizes a power-base dependent on the South? The result, aside from an immense religious bloodbath, might well be a split western Empire and a renewed phase of reconquista warfare...Intriguing stuff, BT.

It's fascinating to see how such disparate cultures can slowly be fused into an imperialist nation-state.