With its declaration of war on Imperial Germany, the United States found itself confronted with strategic problems of a different order of magnitude than it had ever seen before. War with a major European power had come in 1887 (see Anglo-American War, 1887-1888) and – though mostly unprepared, save in her Naval armaments – the United States had secured victory by applying, and sustaining, a well-thought-out strategy. On land, an invasion was mounted to hold Canada hostage and a powerful reserve force used to counter British invasions of the Atlantic seaboard. At sea, a bold thrust into the English Channel placed a choke-hold across the vital windpipe of the British economy and sent chills through a populace that had not been seriously threatened with invasion for three-quarters of a century. These maneuvers immediately placed under threat strategic points of immense value to the British Empire, whose counter-strokes into the Chesapeake and Africa were not so immediately dangerous. If frequently guilty of strategic over-reach, by attempting to do too much with too-few forces, the Americans were fortunate in their opponent. The British Army and Navy were unused to operations in mass, slow to prepare, secure in their – false – sense of superiority, and largely incapable of taking their opponent seriously. At no time were the potentially overwhelming numbers of men and ships available to the British Empire ever brought to bear, nor was its vast industrial apparatus turned to military needs. Above all, the early battles at sea were decisive: with control of the sea, American troops could be moved to threatened points while British reinforcements could scarcely be shifted or supplied. The objects for which the Empire had gone to war were limited, the costs of all-out war very high, and the successive governments at Westminster were smart enough to recognize that the game had ceased to be worth the candle. The United States had made no major strategic mis-step to compare with the British loss of their Channel Fleet and two expeditionary forces totaling almost a third of a million men, and had succeeded in countering British thrusts against American possessions overseas. Thus by acting with rapidity, decision and by minimizing risk where possible, American strategic gambles had paid off – against an opponent who was disorganized, unmotivated and – after the sea-battles in the Channel – shocked almost to paralysis. This would not be the case in 1904.

Against a major land power such as France or Germany, American warplans had a defensive cast: the fleet would be massed in the protected waters of the Caribbean until it was time for a decisive stroke while the army would cover the vulnerable Atlantic ports and colonies against invasion. When war came, the full-tilt German and Dutch invasion of Belgium and France rendered this strategy moot. For political and strategic reasons as well as military necessity, France could not be allowed to fall. This meant deploying the American Army overseas and as far forward as possible, as quickly as possible. Logistics, as always, must rule American deployments: only the infusion of large numbers of fresh divisions could be expected to alter the situation on the frontlines, but to move, feed and equip the necessary men seemed beyond the power of even the most capable staff. The allied counter-blow, an unexpected French and Belgian offensive into the south-western Netherlands, succeeded in wrecking the Dutch army without much reducing the Germany’s overwhelming numerical superiority or providing a serious check to German incursions in Belgium and France. The onset of winter then dragged operations to a standstill, leaving the eastern fringe of the Franco-German border in German hands and opening the frightful spectre of the German army sweeping in springtime from the Champagne to the sea. None of this reduced the urgent need for American troops, or made their deployment any easier.

Despite her decided military inferiority to Imperial Germany, the United States still possessed a powerful navy of eight battleships of the first (‘all-big-gun’) class and thirty-two of the second class, forty-eight cruisers of all classes and eight sea-capable submersibles. The Imperial High Seas Fleet could muster eight new and powerful battleships of the second class, forty-five cruisers of all types and a handful of obsolescent ironclads and armed steamers. One powerful but un-obvious naval asset was the American ability to rapidly mobilize commercial steamships from its large merchant marine, equip them with rudimentary but sufficient barracks and then deploy them across the Atlantic. Though unproven, untested and frankly unprecedented, this vast armada did – in theory – give the American army the ability to reach ports in Europe. In contrast, the almost-equally-large German merchant marine would be sunk, captured or driven into friendly and neutral ports almost immediately.

But for operational security the American troop convoys could not sail until the German High Seas Fleet had been neutralized, or at the very least contained. The prospect of German warships ripping into undefended troopships rendered American admirals pale and sleepless, but their own conception of themselves as aggressive warriors did not permit the employment of the war fleet on mere convoy duty. The older cruisers would serve as escorts while the capital ships and newer cruisers sealed the Danish sound and the ports of the North Sea. The easiest way to support such a blockade would be from British ports, but Britain was preserving a guarded neutrality. The port facilities of Belgium were under enemy artillery fire and the closest American harbor was in the Grand Canaries, a thousand miles from the North Sea, leaving the American Navy dependent on Brest, Cherbourg and the French Channel ports. The entry of other powers into the war and the general collapse of the Dutch would ease this logistical nightmare, but in the first winter of the War this necessary advanced deployment of the American fleets was to expose them to heavy damage and loss, and to risk their defeat in detail.

We may gain an appreciation of the factors involved and their relative importance from an examination of the first naval engagement of the War, commonly called Cadiz or Second Trafalgar. As battles do not occur without some reason, it may be instructive to examine the rationales of the commanding officers and the characteristics of the ships as well as their positions and movements. Since the defeat of the anti-Western rioters in China, Germany had maintained strong garrisons and naval forces in her new bases of Quingdao and Shanghai. With rising tensions in Europe (and with a complete lack of repair facilities for major warships in the German Far Eastern ports) the decision was made to return the Far Eastern Squadron to Europe. This detachment, formed of the new battleships

Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse and

Kurfurst Friedrich Wilhelm, and escorted by the armored cruiser

Aesir, represented a quarter of German total battleship strength. It lay in the harbor of Alexandria in British Egypt when the declarations of war arrived by telegram, taking on much-needed coal and supplies. Despite the fact that his squadron lay at the extreme end of the Mediterranean with a gauntlet of French warships to run and the entire southern rim of that sea taken up by French colonies, Admiral Dietrich von Prittwitz und Gaffron remained in harbor for twenty-four hours before making steam. What he thus lost in time he amply gained in the knowledge that his ships were fully fueled and supplied, and that his intelligence of French dispositions was as complete as possible. When his flotilla departed they were accompanied by ships of the Bremer Mittelsea Line, which von Prittwitz intended to use as mobile sources of coal and stores.

From Alexandria, the Admiral forebore to steer a straight line to Gibraltar and the open ocean beyond, feinting at different times for the Aegean Sea, as if to run for Constantinople, and cruising through Italian waters as though aiming to join the Austrian fleet in the Adriatic Sea. The French Navy could spare no modern ships to shadow such a powerful squadron and concentrated instead on escorting troopships on the route from Algiers to Marseilles. Despite these maneuvers, once west of Sicily the intention of the German Admiral was clear: he must attempt to pass the twin pillars of British Gibraltar and French Tangiers and escape into the wide Atlantic.

The policy of the French fleet was as it ever was; control of the sea would be subordinated to the narrow task of convoying troops. Britain was not yet at war and her senior commanders felt that an attempt to shadow the German squadron too closely might lead to an incident. The United States maintained no permanent naval force in the Mediterranean basin, nor would ships be introduced there in the present crisis. Admiral David Jewell, commanding the American ships based on the Grand Canaries, disposed of an apparently overwhelming force of eight battleships and four cruisers. Yet he refused to divide his ships, declined even to detach his cruisers as a squadron of observation to locate the Germans lest they be trapped in narrow waters and overwhelmed in detail. Instead he deployed his squadrons, not in the mouth of the strait or south of it toward his own base of supply, but across the path of any German steaming for the north, and home.

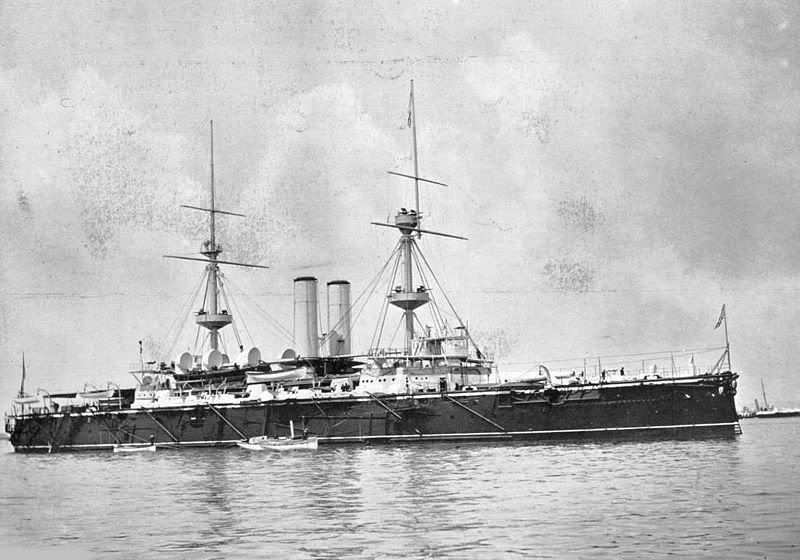

The American battleships were tired and worn from two decades of combat and hard steaming. Four of them were of the

James Madison class, entering service from 1884. The other four were only two years younger and were of the follow-on

Martin Van Buren class. All had seen service against Britain in 1888. The four American cruisers were a decade newer, dating from 1894, and would have been instantly recognizable in a dozen European ports. They were the

Charleston,

Memphis,

Atlanta and

Kansas City – large, fast and powerful in their day, and famous as ‘The Southern Belles’ from their frequent goodwill tours of British and European ports. With the passing of peace, once-black hulls and white superstructures were hurriedly paint-swabbed a muted horizon-gray and bunkers were stuffed with nearly-smokeless British anthracite coal.

Battleship Martin Van Buren docks at Norfolk

USS George Washington. The James Madison

class were identical save for thin armored ‘hoods’ over the main battery guns

USS Charleston in Kiel, 1899

Admiral Jewell and his staff had reasoned that the German Admiral would try to pass his ships through the Strait of Gibraltar in darkness. This was made dangerous by the risk of collision with shipping in the narrow waters, but it must afford the greatest chance of secrecy for his movements. On this principle the American ships were deployed in a triangular formation off Cadiz. The old battleships of the

James Madison class were closest to the Spanish coast, their slightly-younger cousins of the

Fillmore class were almost over the horizon to the west, and the cruisers were stationed to the south, on the point of the triangle. The German ships were all less than five years old and were assumed to be still capable of their designed speeds of 18 knots – a full 22 knots for the cruiser

Aesir. By contrast, the American ships were showing the effects of age and worn machinery. Their cruisers would have struggled to pull away from the German capital ships and their battleships were unable to pursue a fleeing enemy with success. Thus any hope of bringing the enemy to battle must depend upon correctly guessing at his movements and then disposing superior numbers to intercept him.

On the fourth of November the German squadron hurled shells into the French harbor of Tunis, then used the rapid mobility possible to modern steam-powered warships to serve Bone in the same fashion shortly after. Von Prittwitz then took his ships rapidly north, ostentatiously showing them off the coast of Corsica. By this time the French Navy was in an uproar, a state of frantic confusion not lessened by the prompt disappearance of the German squadron as von Prittwitz broke contact and steamed west. Pressed to cover every possible point of attack, the French could only suspend all new sailings from Algiers and mass their available ships there and at Toulon.

Having shaken his pursuers in more ways than one, von Prittwitz turned his ships west toward the narrow mouth of the Mediterranean Sea and called up their highest speed. Though he was seen by passing ships the general lack of wireless communication sets on merchantmen in those days meant that no word of his movements could reach his enemies ahead of his own ships. This employment of high speed and indirect maneuver would have been entirely successful save for the efforts of one Captain Hugh Prescott of the British P&O Lines steamer

Osiris. Not knowing if his country was at war with Germany, Captain Prescott shrugged off his relief at seeing the German ships pass him by and altered course to Port Mahon in Minorca. There his report was put on the network of undersea cables and forwarded to every British consular agent in France and Spain. Within an hour of its receipt in Cadiz a copy was laid on the desk of the American consul, which worthy lost no time in chartering a fast tug to take the message out to the American fleet. For Admiral Jewell and his staff, the news was both welcome and concerning. If the Germans were indeed attempting to break out into the Atlantic by night, they should – by American calculation – have already been sighted.

An anxious day passed, and then a sleepless night. Had the Germans turned back? Had they anticipated the Americans and swung wide into the Atlantic, or worse yet turned south to shell the American naval base in the Canaries? It must have been with profound relief that Admiral Jewell received the signal from the

Memphis at 9:27 am on the 11th of November that ‘Heavy smoke sighted bearing SSE.’

The plume of smoke did in fact indicate the presence of the three German ships. But given von Prittwitz’s haste in steaming away from Corsica, where had they been? Cruising slowly down the Spanish coast, was the answer, transferring coal and stores from German merchant ships that had sailed from Cartagena for that purpose. With added fuel stocks, and with his exhausted stokers given some respite, the German Admiral once again rang his engine telegraphs for ‘Full Ahead’ and pressed on for the Strait.

Seeing the broad, high plume of black smoke – for the Germans were burning soft coal, not anthracite – Commodore Richard Franklin turned his four cruisers from steaming south, side-by-side, to steaming southeast in line ahead, his flagship

Memphis in the van. Several anxious moments passed before the lookouts reported an increase in smoke and an apparent turn to the northwest. Soon after the masts and superstructures of warships could be perceived, and the German squadron was seen to turn to a more westerly heading. As the American cruisers altered course to the south and then swung ‘round to the southwest, their enemy made positive identification and opened fire. That they were uncomfortably close was made clear when the first shell – a 9.4” (240mm) round from

Aesir’s big forward gun – rocketed overhead and raised a waterspout a thousand yards or more past the unarmored American ships.

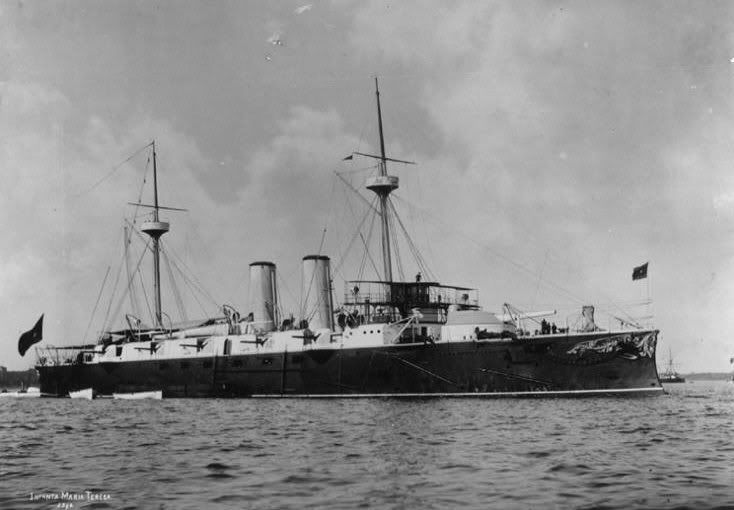

Infanta Maria Teresa

, German-built for the Spanish Navy and near-sister ship to Aesir

, showing off one of her two 240mm guns

A salvo from the

Memphis, however, splashed short. Commodore Franklin had no desire to trade broadsides with battleships and so ordered a simultaneous turn to starboard – north by northwest – and back to parallel the German line. Though the range was long, the American cruisers kept up a steady fire. Their opponents, being less sure of their ammunition re-supply, fired slowly but with care. This tactic paid off at about 10:15am when a 10.8” (275mm) shell from

Kurfurst Friedrich Wilhelm ripped through the side and upper deck of

Atlanta, exploding abaft the fourth stack. The high-explosive blast buckled the arched protective armored deck but failed to penetrate it, leaving the cruiser shaken but not mortally wounded. However, as the Americans were quickly to discover, large German high-explosive shells had the bursting charge wrapped in a tube of wax and incendiary chemicals including phosphorus. Within minutes the rear half of the cruiser was a mass of flame. To save his ship and crew, her captain turned her north into the prevailing wind and doused his magazines in seawater, saving the ship but removing her from the fight.

Any temptation the German Admiral may have felt toward turning on and finishing off the American cruisers was eliminated by his lookouts’ warnings of smoke ahead. They had sighted the four-ship column of battleships of the

Van Buren class, with Admiral Jewell flying his flag from the

Benjamin Franklin. Jewell turned his ships in succession to the south to cross the German ‘T’, all ships breaking out a broad streamer of ‘

Hudson red’ as they opened fire. For von Prittwitz, the choices were stark: to continue on into the massed fire of four battleships while unable to return it, to alter course to the north and head into a possible torpedo attack from the cruisers, or to risk disordering his formation with a radical maneuver. He chose the latter,

Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse heeling hard to starboard as she came around ninety degrees to head northeast.

Aesir, who had been leading the line, missed the signal and turned late, settling into the trailing position of the line rather than speed up and block her sisters’ line of fire.

The Americans were thus completely wrong-footed. For the battleships the fight had become a chase that they could not reasonably hope to win unless critical damage slowed their enemy. The American cruisers were now also behind and to port of the speeding foe, and though they could still steam the German shells had damaged them heavily. With the tactical situation favorably in hand and the range opening by the minute, one can only imagine the sentiments on the

Kaiser Wilhelm’s flag bridge when the lookouts again spotted smoke… ahead. It was, of course, the old and slow ships of the

Madison class, with Rear-Admiral Glossup leading from the

Henry Clay. Though their stokers and engineers had been straining every muscle, and despite the fuming volcanos of coal smoke vomiting from their boilers, the old battleships had scarcely reached sixteen knots in their run south. Fortuitously, they were now placed exactly across the enemy’s path.

Glossup had, in general, three choices. The first was to turn sharply to starboard (west) to open fire, then reverse his course to parallel the German line, hoping to slow them down before they passed him and escaped. The second was to continue to the south, then reverse course – essentially the same maneuver as the first, but at a closer range. The last was to steam directly toward the German squadron and rapidly close the range, either altering course at the last moment or passing the enemy on the opposite course at very close range. We must bear in mind that Admiral Glossup had no more indication of the position of other forces than their smoke-plumes and was not only out of contact with his flagship but heavily out-matched. The prudent course would be to open fire, reverse course and maintain contact for as long as possible. The Admiral chose to attack instead, as directly and at as close a range as possible. The American line altered course to the southwest, steaming head-on at the German squadron.

One account, written years after by an officer in the

Andrew Jackson, third in line behind the

Clay and the

Madison, states that the Germans ‘flinched’, or turned away to the east or south before resuming their northeasterly run. If so, Admiral von Prittwitz must have speedily reacted to the threat and then realized he had nowhere else to turn: east was a neutral coast, south no port that could offer fuel or refuge, west only more enemies. In any case, he opted to close the range, endure the enemy’s fire and then – hopefully undamaged in any critical part – steam away to the north.

Modern gunnery had been concentrating on landing shells on target at open ranges since the first American battleships hit the water in 1884. Over the two decades since, fire control and ranging systems had been developed and training made a regular part of every ship’s routine. In general, the American equipment was older but their officers and crew were superlatively trained and experienced in its use. German optics and machining were better and their crews were well-drilled, though not as experienced in live-fire. In this case it was to make not a particle of difference: the forward guns of

Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse landed a direct hit on the metal shell covering the forward guns of the

Henry Clay at less than six thousand yards. The shell was armor-piecing and so did not detonate until it had penetrated the armored conning tower behind the turret, but half the main armament was put out of action and most of the gun crew killed or disabled. In response, her captain ported his helm to pass in front of the

Kaiser and then turned back southwest, passing the German flagship at a range of a mile and a half.

Madison followed suit;

Jackson and

George Dallas could not turn as they would have been rammed, and so continued down the other side of the German line.

One survivor compared the next fifteen minutes to a gangster shootout with machine-guns at twenty paces. Assuming a gun could be brought to bear there was no chance to miss, and at such a close range even the old, relatively low-velocity 12” guns in the American main batteries could penetrate any armor. Shells from the

Clay entered the

Kaiser at a 45 degree angle forward of her armored belt and raked her innards, blowing out at least one boiler-room.

Madison’s four-gun salute shredded another set of boilers and set fire to the propellant store for the main guns. The dying men trapped in the magazines hit the flooding handles, dooming themselves but saving the ship from immolation. In turn,

Kaiser’s 200mm secondary armament wiped

Clay’s bridge off the ship, killing everyone from the admiral and captain down to the seaman at the wheel. Auxilliary control kept her headed southwest, taking her down the full length of the German line to come at last to a halt, wreathed in steam, smoke and flame. Reloaded,

Kaiser’s 275mm main armament returned the favor to

Madison. All four shells penetrated the belt armor and wreaked havoc inside. The 6” secondary guns were set in slots in the armored superstructure, but this protection did not save them. Enemy shells detonated behind the protective shield, setting off the ammunition piled in the ready racks behind the guns. The blast ripped

Madison like a can-opener and fatally racked the rivets holding her hull-plates to her ribs. With her boilers sundered and her engines stilled there was no power for the pumps; flooding below the waterine and blazing above,

Madison was doomed.

While

Kurfurst Friedrich Wilhelm and

Aesir scrambled to avoid the wounded, veering

Kaiser Wilhelm and rained additional blows on the hapless

Clay and

Madison,

Jackson and

Dallas took the other two German ships from the opposite side. At such a close range even the 6” secondary guns on the American battleships could not fail to hit and penetrate. Though no immediately fatal damage was done, both the German battleship and cruiser sustained hits below the waterline as well as damage to their engineering plants.

Aesir would be brought to bay by the surviving American cruisers and dealt a killing blow by

Franklin and

Hancock as they came up.

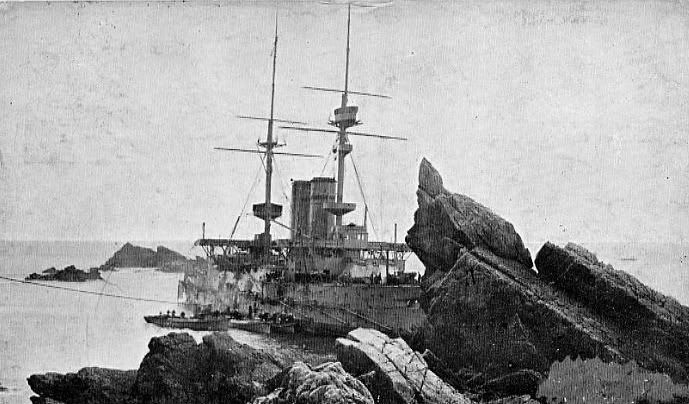

Kurfurst Friedrich Wilhelm staggered off to the east, no longer under any steerage save that provided by her propellers, and heaved herself onto the rocks to avoid surrender.

Kurfurst Friedrich Wilhelm

aground off Cape Trafalgar, November, 1905

It was a century and a month after Nelson’s stunning triumph. It was disorganized, chaotic, rapid-paced and brutal, a collision of mechanical behemoths with literally explosive ferocity. The decisions of all three admirals (and one Commodore) would be the subject of discussion, argument, praise and condemnation, the deaths of Admirals von Prittwitz and Glossup notwithstanding. The infant German Navy had acquitted itself well in its operations, and its ships were excellently designed and manned. The older American ships had paid a sobering price despite their numerical superiority, but the victory was undeniable: the German presence in the Mediterranean had been swept from the seas.