Union Terminal in St Louis was still almost new, the brick and marble and black iron shining in a misting rain that pattered high overhead on the vast train shed. They debarked from the private car into the bustle and roil of the busiest train station in the world, noise and color and odor overwhelming after the dark quiet comfort of Makhearne’s rolling suite. Wisps of coal smoke and steam eddied underneath the roof, throngs battled up and down the walkways between the cars, and the noise… Dozens of locomotive panting and jetting, wheels and brakes squalling, porters bawling, children shrieking in delight and terror… “Come, let us go to the lobby,” Ronsend urged, slipping Ann’s arm under his own. “Rogers will see to the baggage while we secure a car. The sooner we are out of this, the better.”

The best of downtown St Louis stretched west from the riverbank along a series of grassy malls, streets fronted in shops of gray stone or red brick and topped with stories of apartments. Copper roofing had mellowed to a verdant gray-green, metalwork was picked out in crisp black paint and the cobblestoned streets were newly slathered with a concoction of petroleum tar, sand and gravel. Had the signs not been in English one might have imagined oneself in a town on the Franco-German border, save that St Louis had scrubbed and primped and painted itself into exhaustion for the Fair and so was both cleaner and in better repair than its European sisters. The train station was a French chateau fantasy in native stone and stained glass, and it perched on the north side of Market Street, in pride of place midway down the strip between the river and the fairground park. Behind the station, discreetly hidden from view by the deceptive mass of the building, lay acres of railroad tracks, freight yards and machine shops. All of the main railroad lines ran past this jungle of rails and ties, cars and locomotives, men and machines, and both the yards and the rail lines were frantically busy.

For the Fair, St Louis had laid a double-track of tramway rails along the central mall with festively-painted trolleys rolling past every ten minutes during daylight hours. Ronsend slipped Rogers a banknote with a hurried instruction. “Deliver our baggage to the Audubon Hotel and make certain your accomodations are secure. Then – enjoy the Fair, Rogers! Mrs Shea and I will not require your services until four o’clock on Thursday. Cover your expenses from that, and if you require more then a note to the desk clerk at the Audubon will find me.”

After the clamor of the train shed, the electric trolley was delightfully quiet – so much so that they could easily hear the conversations of strolling couples on the wide concrete side-walks. Not for St Louis the mud and dust of unpaved streets and split-board walks over puddle-cratered entries. The self-proclaimed Gateway City of the West would spare no effort or expense to impress her visitors – and, it must be noted, the canny burghers of St Louis had shrewdly calculated that the Fair traffic would pay for these splendid improvements many times over. A brief rush along the Mall, a scant glimpse of cathedrals and museums and vast buildings through the April mist, and they were at their destination: The Audubon Hotel, built on the promise of the Fair and opening almost in tandem with it. As with much else, no expense had been spared to impress the customers, and as with the train station, much lay hidden behind the clifflike gray stone of the front wall. The lobby was vast and opulent, though less in the style of a grand European hotel and more in a new, bolder American mode. Black and white marble graced the floor and walls, enormous electric chandeliers exploded from the ceiling in cataracts of crystal. Off the lobby were controversial American innovations – two restaurants, one a shockingly casual ala carte café with walls of plate glass and the other a grand and formal establishment complete with orchestra. On the other side of the lobby, mirrored doors opened onto a virtual boulevard of shops: florists, candy-makers, milliners and more. The rear areas of the lower floors were made up of smaller, cheaper, plainly-furnished rooms, while the street-frontage ran the gamut from fine accomodations to suites of palatial size and extravagant luxury.

The desk clerk did confirm that Mr Michael Cullen and party were in residence. He gently declined Ronsend’s request for the number but promised to forward a message containing one of the hotel’s own gold-leaf-embossed cartes de visite. This security precaustion was set at nought for Ronsend could clearly see him place it in a pigeonhole whose brass plate bore the floor and number. It was easy to then present his own name and allow the clerk to check them in. Accepting the brass key and its gold-colored tag, Ronsend again took Ann’s arm and strolled with her to the gleaming brass elevators. Arriving at their floor he tipped the boy at the controls and, once out on the plush carpet of the waiting area, paused for the doors to close.

Six elevators opened onto an area the size of a townhouse parlor, thickly carpeted beneath a group of chairs and tables – a place for members of a party to wait for others to join them. The chamber was deserted, as were the hallways that opened from it like the arms of a T. “We should go to the staircase at the end,” Ronsend suggested. “Donneval’s suite is only one floor up.”

Presumably, everyone was at the Fair and the staff had completed their duties for the day. They saw no-one and more importantly they were not seen. At the staircase, Ronsend paused and looked carefully around the walls and ceilings. Up the stairs they went, slowly, Ronsend inspecting the structure carefully at every step.

“Looking for traps?” Ann asked, and he shook his head, then nodded. “Frost and Messoune like traps, the nastier the better. Donneval and I have always preferred… a little sensor like that one.” He pointed to a dot the size of a nailhead. “Either would tell us something, but not enough for a conclusion. Still, whoever it is will know we are coming.”

The hallway was a copy of the one below, the widely-spaced doors identical save for the numbers on the brass plates, the carpet thick and soundless. No-one was in view. Makhearne’s room as on this side but at the mid-point, so Ann set out for it with direct strides, only to have Ronsend gently hold her back. “There are two ways we can do this,” he said, keeping his voice low but not whispering. “Break the door in – which gives us some surprise but is messy to explain, after – or simply knock.” She nodded, and they walked silently down the hall. Ronsend motioned her to one side of the door and stepped to the other, reaching over to knock softly on the door.

Moments passed. Ann motioned for him to knock again, but Ronsend frowned and waited instead. Gently he reached into a pocket and slipped on a gray calfskin glove, then removed a small black device from his jacket. Carefully he lowered his hand, pressed the tip of the cylinder to the lock and then rotated the door handle. The door opened and exhaled a faint breath of air: it was now unlocked. Ronsend eased the door wide enough to slide through; with a silent sigh and a roll of her eyes Ann followed, hands lifting a dainty pistol from her clutch-purse.

Past the antechamber the room broadened into a large sitting area, furniture grouped to face a fireplace and topped by an ornate mantelpiece; on either side of the empty grate double glass-paned doors opened onto a balcony that ran the width of the suite. Jutting just above the top of a broad sofa upholstered in toacco brown suede was shock of gray hair. Ronsend motioned Ann back into the hall, eased the door shut and rapped loudly. A silent minute passed before the lock clacked and the door opened, framing a dapper older man clad in a sober black suit: Makhearne’s valet and genial man-of-all-work, Roarke. Neither had ever met the man, but Ronsend had read in Makhearne's letters a mention of him along with descriptions of the rest of his household.

“Mister Shea, I presume!” he exclaimed, a wide but very proper smile spreading over a round and merry face. “And this must be the lovely Mrs Shea! Please do come inside. Mister Cullen has been waiting most hopefully for your arrival. Regrettably, he has stepped out but I was told he would return shortly.”

Ronsend paused in the entryway. “And Simpkins…?”

Roarke’s mouth twisted down in a sham of regret but his eyes twinkled. “You’ve caught us out, sir, I’m afraid. Come out, Simpkins, and pay your respects to our guests.” The door to the coat closet opened just enough for a short, wiry, dark-haired man to slip through. He had the grace to look faintly embarrassed, which deepened as he shifted the sawed-off double-barreled shotgun from his right hand to his left, using the freed hand to sweep the flat cap from his thinning hair. “Nice trick with the door, sir, if I may say so.”

“Expecting someone else?” Ronsend inquired, an arch smile thinly laid over genuine concern.

“One never knows who may come to call,” Roarke said with gentle regret. “The master has unusual… friends, and there are others who do not always seem to have his best interests at heart. We have become… cautious.” Then more briskly, “Please! Do come in! And permit me to serve you. An iced beverage, perhaps? St Louis is so very warm this spring.”

“One doesn’t often see armed men lurking in a coat closet,” Ann ventured as they were ushered into the sitting area.

“Neither Simpkins nor myself is what one would call a proper gentleman’s attendant,” Roake said, eyes twinkling again, “though I was in service to the second Earl of Thrail in Ireland, before the Rising. My enthusiasms got the better of me that year, I’m afraid. And so I came to America, only to find myself somewhat at loose ends, as they say. Mister Cullen said he had need of a man with, hmmmm, skills out of the ordinary line, if you see what I mean? And I gave a good word for Simpkins… He was a gamekeeper then, and always handy with the guns.”

“Does Mister Cullen have much call for your – how did you say – skills out of the ordinary line?”

“I’ve been with the master twenty-three years,” Roarke said. “Men have tried to break into the house eleven times, six times they’ve shot at the house or carriage, nine times the master has been assaulted and three times we believe there was intent to carry him away.” His smile crooked into a grin. “It has been an interesting time.”

Ronsend smiled grimly back. “Wealthy and prominent men do attract undue and unwanted attention.” They settled onto the settee and Roarke went to putter with bottles at the bar. “Tell me, Roarke, if you can, why Mister Cullen summoned us here?”

“I’m afraid the master does not always confide in me,” the valet said, whisking around a silver tray laden with crystal glasses, silver bowls, tongs and sprigs of mint. “But Simpkins has just signaled me from the balcony that he has espied the master, so I have no doubt you will shortly be able to satisfy yourself. Julep?”

Makhearne entered with a heavy tread and a frowning face that lifted only for a moment while he greeted his friends. “As good as it is to see you both, I am afraid I have some concerning news to impart.” He took a strong pull from the mint julep and handed it back to Roarke unfinished. “Excellent, Roarke – as always – but I am in need of a clear head. I desire you to take these letters to the post office and then Simpkins and yourself may have the rest of the day off. Mr and Mrs Shea will dine with me in the restaurant, or perhaps on the Fairgrounds if the whim takes us.”

Makhearne, Ronsend and his wife enjoyed the view from the balcony while Roarke tidied up the bar. Once he and Simpkins were safely gone, Makhearne ushered them back inside and settled himself in a chair while they perched on the settee.

“You simply must tell us what all of this is about,” Ann said crossly. “Why, we half suspected the telegram wasn’t from you at all. Not to mention dragging us half-way across the continent on so little notice.” Then a flicker of a smile relieved the severity of her expression. “Though meeting Mister Rourke certainly was… interesting.”

“I realize I’ve never had the two of you to visit me at home, and I never involve Roarke and Simpkins in my, um, unofficial business if it can be helped. It never occurred to me that you had not met.” Makhearne’s mouth twisted in a rueful grimace. “And here I thought I was being clever to use both sets of initials. Ah, well… my apologies you have, and sincere ones, too. The problem is both simple and complicated. One of my employees has disappeared. While it could be no more than his usual disdain for the ordinary conventions of things like clocks and calendars, it could be something more… I rather think, under the circumstances, it is.” Ronsend inhaled as though to speak and Makhearne lifted his hands in appeal. “A moment more, I beg you, and I will say all I know.”

“Your work has taken you to California, and I know that the demand for automobile steamers is high. I have invested heavily in another growing industry – electrical gear. Light bulbs and fixtures, improved telegraphy and telephonics, cables, insulation, dynamos and generators and… well, the list goes on at some length. Suffice it to say that the world is moving from water and steam power to electricity, and the demand for equipment is enormous. The demand for improvements and for new types of apparatus is extremely large, and where there is that sort of demand, the man who can harness genius and tame the technology can make a fortune.

“Not that money was my sole concern. The strange people we saw coming through that gate in Nemor’s lair… Well. You can’t bring a technology along too far in advance of its natural time, and this is the time for electricity. I hoped to find someone I could entrust with the basics of parachronic theory. We may be decades – or a century – away from controlling a gate, but even small applications like a warning device could be useful…

“At all odds, I found exactly the man I needed, or I should say that he found me. I was in a patent war with Edison and had put the word out for anyone who had left his employ. This fellow came around, Eastern European, hardly spoke English. I didn’t pick up on him at first, but when I ran the name through the library later…” Ronsend made to speak again but Makhearne waved him down.

“His name is Tesla, Feric – look it up. Jozsef is his first name in this timeline.” Ronsend’s attention turned inward, a sure sign that he was accessing some internal database. While he was absorbed, Makhearne poured cups of tea from the service Roarke had left on the table, and at the same time attempted to answer Ann’s questions.

“As the differences in timelines open up,” he said, “the people become more different. If a major war sweeps through an area, people who might otherwise meet, marry and have children are killed or driven out as refugees. There are certain focal points – the upcoming global war with Germany is almost a contstant – and, despite everything, certain names and abilities keep cropping up. In almost every timeline, when you get to the age of railroads there are Vanderbilts and Brunels and Josephs. For invention, there is usually an Edison, or a Bergman, or a North. Electricity seems to attract a Tesla, a Francois, a Duleny. Here we have both an Edison and a Tesla, though one is Arthur instead of Thomas and the other is Jozsef rather than the more usual Nikola. There are some other small differences, but the fact remains there is a genius of electrical invention named Tesla, who has disappeared.”

“Disappeared?” Ronsend nodded. “That is the T you mentioned.”

“Precisely. I’ve been funding his researches, and the man is undoubtedly a genius. He is also erratic in his habits and prone to distraction if some new idea comes along – which seems to be daily. He and Edison fell out over alternating current. Tesla developed the idea and took it to Edison, who bought up the patent rights and then fired him.” Makhearne shook his head. “I might not have prevailed against Edison in the courts had he not been so intolerant of the inspirations of others… But that is neither here nor there. Tesla has been working on parachronicity for me and pursuing some of his own ideas on the side. We wanted to show off a bit, attract some investors for some new products… and Tesla is a showman worthy of the Bailey Brothers.”

He shrugged. “I sent him here with freight-cars of apparatus. His laboratories are set up, the display areas are ready, and yet the man himself… has vanished.”

“Taken by Frost and Messoune, you think,” Ronsend prompted.

“That is the worst case from our point of view as it deprives us of our researcher and possibly puts his effort onto the other side of the scales. But from a practical point of view it does not matter if he was taken or seduced away, only that he is gone.”

“It has been many days and the trail is doubtless cold. What do you propose to do, and what do you need from us?”

Makhearne sipped at his tea and frowned into the cup. “I think I must go to Germany and see if I can uncover any trace of him. And that means that Michael Cullen must die.” His frown lifted for a moment. “I’m quite tired of pretending to be a man in his seventh decade, so this only pushes up the inevitable by a year or two. My will names you as the executor, and I’ve taken care to cache some funds, so that will all be right. Are there any companies of mine that you would care to have?”

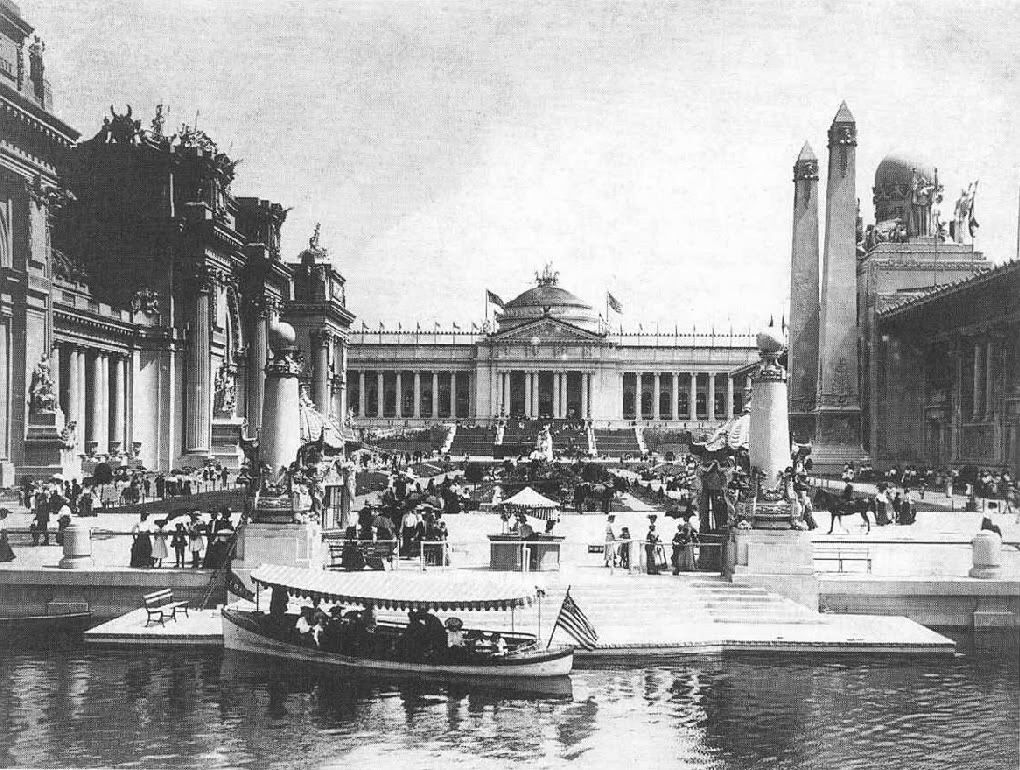

They dickered for a few moments and arrived at a short list. “Fine. Then that is that,” Makhearne said briskly. “I will telegraph my business manager in the morning. Let us take the remainder of the day and go see the Fair – I can at least show you Tesla’s laboratory and display area in the Palace of Electricity. There may be some clue whose meaning is evident to you.”

As they rose, Ann laid a small hand on the old man’s arm. “I have no acquaintance with them, yet I am moved to ask what disposition you have made for your men.”

“They will each receive a most generous annuity. Neither Roarke or Simpkins will need to work another day unless they wish.”

“It is well. I believe sometimes you men see the world as an inanimate place, full of obstacles and levers. I hope you will not take it amiss if, from time to time, you are reminded that it is a place of people, too.”