Well, people like him do have some uses...especially when the peasants start getting uppity...

Corsican Dawn: The Rise of House Obertenghi

- Thread starter unmerged(60841)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The next update will follow this immediately, it's another narrative and I hope you enjoy it. I'm going away for a long weekend so it might be the last update for a little while.

English Patriot: Indeed, Demetrio is very much a cause for concern given that he's in line to inherit.

EmprorCoopinius: That's what I figured. There's a bit of hope for Alberto and Margherita yet though.

Triv: Glad to have you on board and glad you like the AAR, there's definitely more of both to come.

Aussieboy: Always look on the bright side, right?

Thanks everyone for reading and commenting, I appreciate it.

English Patriot: Indeed, Demetrio is very much a cause for concern given that he's in line to inherit.

EmprorCoopinius: That's what I figured. There's a bit of hope for Alberto and Margherita yet though.

Triv: Glad to have you on board and glad you like the AAR, there's definitely more of both to come.

Aussieboy: Always look on the bright side, right?

Thanks everyone for reading and commenting, I appreciate it.

Alberto and Germano

As a rule, Alberto loved returning home to Corsica. He delighted in the smell of the sea crashing against the cliffs below the castle he grew up in, he took comfort in the chatter of the peasants at the docks, unrefined and uncomplicated, haggling over the price of fish and disseminating gossip. To this day, his heart stirred a bit when Corsica appeared on the horizon, and he eagerly watched as it grew ever larger in his view. He knew no love as absolute as that of his children, their arms clutching him when he returned, their lips overflowing with stories of their activities in his absence. Margherita appeared also, at least for a brief, all too fleeting moment delighted and pleased, a smile playing upon her lips and in her eyes that Alberto cherished on those evenings far from home, and even many of those at home, when the pallor of her depression settled over her. Yes, Alberto loved returning to Corsica, he knew of no pleasure in this world which compared with it. Today, however, he knew he would eagerly trade all the comforts of home to leave this place, to go anywhere but Corsica. Yet in Corsica he remained, poised outside his bastard’s door, attempting to summon the courage to enter.

When he arrived earlier at the rapidly gentrifying castle, no children’s voices assailed him, nor did even Margherita appear to welcome him back from his most recent trip to Mallorca, where he formalized the preparations for his long-anticipated proclamation of himself as the Duke of Mallorca, an event he hoped would remove the stigma of the derisive nickname “the Pauper Duke” as to Alberto at least, a double Duke hardly seemed a pauper. No, no one appeared to welcome him, not even his coterie of daughters, Adelasia, Brunilde, and Giuditta, stairstep children so close in resemblance and in age that they often appeared almost indistinguishable from one another, though each of them would object vociferously to any such statement. Instead of his wife’s open arms or his children’s cries of delight, the only figure which welcomed Alberto to the castle had been Azzo Terzi. At first, Alberto thought that a grave tragedy must have struck, or that news of a declaration of war from Pisa- who claimed Corsica and Cagliari by right of Alberto’s renunciation of vassalage- or some other great power had arrived in his absence. Yet, though Azzo’s news lacked any such importance of state, the words he did speak chilled Alberto’s heart to the core.

Of course, he knew the boys never developed the kind of closeness he hoped for in his children. The girls it seemed entertained themselves, forming a bond distinct and apart from Demetrio and Germano, endlessly amused by playing with one another, indeed, he knew that none of them could even recall a time when their sisters were not with them, they slept in the same bed, shared the same toys. Alberto suspected in this way their mother’s inconstant mood, so poignantly felt by him, did not rest as heavily upon their hearts. They knew no other state from her, and expected nothing else. Their self-sufficiency pleased Alberto; indeed, their closeness reflected the kind of relationship he had long hoped for between his sons. Margherita gave birth to his youngest daughter, Giuditta, nearly four years past, and Alberto did not expect any more children.

Yet Germano and Demetrio displayed no such close kinship. Alberto knew the transition from the foster son of a tailor to that of the bastard son of a Duke weighed heavily upon Germano. The boy little understood the intricacies of court which shunned him as abastard, nor, already five years old when he arrived at court, did he comprehend why this transformation need take place at all. His tutors informed Alberto he grew reclusive, taking every opportunity to retreat to his chambers with his dog, Basso, the only remnant of his prior life, and read pagan authors whose alien worlds he evidently found much more appealing than his present. He hung in the background during the jubilant reunion celebrations that coincided with Alberto’s return, approaching his father only after the others departed, insisting on handshakes rather than hugs, though Alberto always drew the boy in for an embrace despite this. He spoke rarely, and the words that did leave his mouth often hinted at thoughts that were better left unsaid, from a young age he claimed to have imaginary friends, more recently Azzo told him he began to insist these friends, who he now claimed to recognize as Pagan gods as diverse as Zeus and Janus; spoke to him.

Despite Germano’s reluctance to engage the court or any human being for that matter, his presence clearly grated on Demetrio. Alberto could not deduce precisely why, he attempted to favor the boys equally, and in many respects, Demetrio presented him with an admirable son. Praised universally by his tutors for his excellence in all disciplines, especially by Azzo who sometimes joked with Alberto that Demetrio would soon surpass him as chancellor, despite all the obvious advantages of his position over Germano, Demetrio still evidently found his elder brother objectionable. Alberto saw the dagger glares he tossed Germano’s way, the envious want in his eyes when Alberto drew Germano in for a reluctant embrace, even though Demetrio himself always arrived and welcomed his father first. Alberto long attributed this to the simple gap in the boy’s age, and his vague sense of entitlement to a similar feeling he himself had sometimes possessed in his youth as a disaffected count, but the revelation of this new horror forced him to revise that opinion, whatever tragedies Demetrio suffered, surely none could possibly explain this unwarranted act of cruelty, of hatred. Indeed, even in this despicable enterprise Demetrio showed himself to be both cunning and intelligent. He knew full well that a direct assault on Germano would result in little more than his humiliation- despite his seclusion, the fact remained that his elder brother, significantly older, could easily best Demetrio, a much smaller boy, with ease. Recognizing this, Demetrio sought to strike at the heart of his opponent, and seeing that Basso was the only thing which Germano apparently felt anything strongly about, destroyed that one thing. The entire affair revealed such a hideous, almost unspeakable cruelty that Alberto struggled with himself to find an answer. Perhaps his mother’s grief, her unchecked and nearly mad mourning for Chiano infected him in the womb, could he have felt the change in her disposition after her death, been damaged by it? Or perhaps the a simpler explanation sufficed, that with Alberto absent, Margherita withdrawn, Germano reclusive, and his sisters thoroughly occupied with one another, Demetrio envied any rival for any person’s affection, and resolved to destroy them, doing so in a manner of such cruelty that it frightened his father and left the servants whispering in fear of him. With his father absent. The thought stung Alberto, perhaps the strongest indictment yet of his failings as a father, even as a man. He told himself his travels were essential to the survival of the duchy, yet he knew that in many cases deputies could accomplish the same tasks, knew that his physical presence would not make or break the situation. He knew, though he rarely admitted it even to himself, that he feared Corsica at times, feared the chill of his bed and his wife’s moods, pressures of an entirely different caliber than those of state.

He shook these thoughts off, resolving to speak with Margherita. Too much lingered between them unsaid, a gulf of silence which threatened to envelop their relationship, and now, Alberto realized, perhaps even their children. Soon he thought, after this. I must comfort Germano now. The boy needs me. With a deep breath, he gently pushed open the door to Germano’s room, stepping in. “Germano? Papa’s here…how are you?” he kept his voice soft. Azzo told him Germano had refused to leave his room since the incident.

The room, Alberto noted, reflected the boy’s state, disheveled, it appeared clear that Germano turned away his servants when they came to clean the place, half-eaten meals littered the floor, the painstakingly composed books Germano was so fond of open and strewn with equal indifference about the room, a film of dust gathering on their pages. Germano himself sat upon his bed, his knees tucked to his chest, rocking gently, a distant glean in his eye. To Alberto’s surprise, he spoke, his words distant and surreal. “Yes. Zeus told me you were coming.”

Alberto arched a quizzical brow, confused at the boy’s speech..”Zeus..?”

Germano replied with a sudden intensity, “Yes father..Zeus…he’s told me the Christian god has him in chains. But he wants you and I to save him.”

Alberto brushed aside these ramblings, “Son. You must never speak so in public or private. There is only one God. Azzo told me about Basso, I am deeply sorry…would you like us to go and get a new dog in the morning?” He felt he was bumbling, incredibly ill at least with his own child.

Germano shook his head vigorously, “No, no, Basso is all right. It’s been explained to me by…others…I don’t need another dog.” A distant, almost eerily empty smile crept across the boys face, to Alberto, he seemed bizarrely content with this pronouncement.

Alberto nodded his head slightly in agreement. The boy remained overwhelmed, and rightly so perhaps, Basso had been his only solace. He seemed to pay little attention to Alberto’s words. He would try again in the morning, he resolved..indeed, he would try every day, as he suddenly realized that he had come to the conclusion that he must remain in Corsica for quite a bit longer than he anticipated before. He spoke briefly to Germano again. “That is well. I will come to see you again tomorrow, son.” He wrapped an arm around the boy, pulling him close for a moment. “I love you Germano,” with that he departed, leaving the boy as he found him. Recently, news reached him which gave him hope for Germano’s future. Elvira de Coimbra, heiress of the duchy of Braganza, had recently been widowed by her husband, her father, a destitute exile from his own father’s court who wandered the Mediterranean seeking handouts, had met with Alberto in Corsica, expressing his willingness to marry the recently eligible Elvira to an Obertenghi. Alberto, mindful that the fact that he even sought out the Pauper Duke revealed the true extent of his need, said that Germano would be eligible. The man hesitated briefly, asked for a larger sum, and agreed. Alberto hoped this would secure a future for Germano- one far from Corsica where his status would matter less. He closed the door gently, turning his thoughts to the next item on his agenda.

He must speak with Margherita…Demetrio’s lecture and discipline must come from a united front, one united as it had not been since his birth. Alberto suspected without his wife, without all of her, no amount of words on his part would repair their son, or their family. He began to walk toward Margherita’s rooms, his steps filled with purpose, hope, and an aching sense of fear, as Alberto could not imagine what recourse he would have if he failed to rouse her to action.

As a rule, Alberto loved returning home to Corsica. He delighted in the smell of the sea crashing against the cliffs below the castle he grew up in, he took comfort in the chatter of the peasants at the docks, unrefined and uncomplicated, haggling over the price of fish and disseminating gossip. To this day, his heart stirred a bit when Corsica appeared on the horizon, and he eagerly watched as it grew ever larger in his view. He knew no love as absolute as that of his children, their arms clutching him when he returned, their lips overflowing with stories of their activities in his absence. Margherita appeared also, at least for a brief, all too fleeting moment delighted and pleased, a smile playing upon her lips and in her eyes that Alberto cherished on those evenings far from home, and even many of those at home, when the pallor of her depression settled over her. Yes, Alberto loved returning to Corsica, he knew of no pleasure in this world which compared with it. Today, however, he knew he would eagerly trade all the comforts of home to leave this place, to go anywhere but Corsica. Yet in Corsica he remained, poised outside his bastard’s door, attempting to summon the courage to enter.

When he arrived earlier at the rapidly gentrifying castle, no children’s voices assailed him, nor did even Margherita appear to welcome him back from his most recent trip to Mallorca, where he formalized the preparations for his long-anticipated proclamation of himself as the Duke of Mallorca, an event he hoped would remove the stigma of the derisive nickname “the Pauper Duke” as to Alberto at least, a double Duke hardly seemed a pauper. No, no one appeared to welcome him, not even his coterie of daughters, Adelasia, Brunilde, and Giuditta, stairstep children so close in resemblance and in age that they often appeared almost indistinguishable from one another, though each of them would object vociferously to any such statement. Instead of his wife’s open arms or his children’s cries of delight, the only figure which welcomed Alberto to the castle had been Azzo Terzi. At first, Alberto thought that a grave tragedy must have struck, or that news of a declaration of war from Pisa- who claimed Corsica and Cagliari by right of Alberto’s renunciation of vassalage- or some other great power had arrived in his absence. Yet, though Azzo’s news lacked any such importance of state, the words he did speak chilled Alberto’s heart to the core.

Of course, he knew the boys never developed the kind of closeness he hoped for in his children. The girls it seemed entertained themselves, forming a bond distinct and apart from Demetrio and Germano, endlessly amused by playing with one another, indeed, he knew that none of them could even recall a time when their sisters were not with them, they slept in the same bed, shared the same toys. Alberto suspected in this way their mother’s inconstant mood, so poignantly felt by him, did not rest as heavily upon their hearts. They knew no other state from her, and expected nothing else. Their self-sufficiency pleased Alberto; indeed, their closeness reflected the kind of relationship he had long hoped for between his sons. Margherita gave birth to his youngest daughter, Giuditta, nearly four years past, and Alberto did not expect any more children.

Yet Germano and Demetrio displayed no such close kinship. Alberto knew the transition from the foster son of a tailor to that of the bastard son of a Duke weighed heavily upon Germano. The boy little understood the intricacies of court which shunned him as abastard, nor, already five years old when he arrived at court, did he comprehend why this transformation need take place at all. His tutors informed Alberto he grew reclusive, taking every opportunity to retreat to his chambers with his dog, Basso, the only remnant of his prior life, and read pagan authors whose alien worlds he evidently found much more appealing than his present. He hung in the background during the jubilant reunion celebrations that coincided with Alberto’s return, approaching his father only after the others departed, insisting on handshakes rather than hugs, though Alberto always drew the boy in for an embrace despite this. He spoke rarely, and the words that did leave his mouth often hinted at thoughts that were better left unsaid, from a young age he claimed to have imaginary friends, more recently Azzo told him he began to insist these friends, who he now claimed to recognize as Pagan gods as diverse as Zeus and Janus; spoke to him.

Despite Germano’s reluctance to engage the court or any human being for that matter, his presence clearly grated on Demetrio. Alberto could not deduce precisely why, he attempted to favor the boys equally, and in many respects, Demetrio presented him with an admirable son. Praised universally by his tutors for his excellence in all disciplines, especially by Azzo who sometimes joked with Alberto that Demetrio would soon surpass him as chancellor, despite all the obvious advantages of his position over Germano, Demetrio still evidently found his elder brother objectionable. Alberto saw the dagger glares he tossed Germano’s way, the envious want in his eyes when Alberto drew Germano in for a reluctant embrace, even though Demetrio himself always arrived and welcomed his father first. Alberto long attributed this to the simple gap in the boy’s age, and his vague sense of entitlement to a similar feeling he himself had sometimes possessed in his youth as a disaffected count, but the revelation of this new horror forced him to revise that opinion, whatever tragedies Demetrio suffered, surely none could possibly explain this unwarranted act of cruelty, of hatred. Indeed, even in this despicable enterprise Demetrio showed himself to be both cunning and intelligent. He knew full well that a direct assault on Germano would result in little more than his humiliation- despite his seclusion, the fact remained that his elder brother, significantly older, could easily best Demetrio, a much smaller boy, with ease. Recognizing this, Demetrio sought to strike at the heart of his opponent, and seeing that Basso was the only thing which Germano apparently felt anything strongly about, destroyed that one thing. The entire affair revealed such a hideous, almost unspeakable cruelty that Alberto struggled with himself to find an answer. Perhaps his mother’s grief, her unchecked and nearly mad mourning for Chiano infected him in the womb, could he have felt the change in her disposition after her death, been damaged by it? Or perhaps the a simpler explanation sufficed, that with Alberto absent, Margherita withdrawn, Germano reclusive, and his sisters thoroughly occupied with one another, Demetrio envied any rival for any person’s affection, and resolved to destroy them, doing so in a manner of such cruelty that it frightened his father and left the servants whispering in fear of him. With his father absent. The thought stung Alberto, perhaps the strongest indictment yet of his failings as a father, even as a man. He told himself his travels were essential to the survival of the duchy, yet he knew that in many cases deputies could accomplish the same tasks, knew that his physical presence would not make or break the situation. He knew, though he rarely admitted it even to himself, that he feared Corsica at times, feared the chill of his bed and his wife’s moods, pressures of an entirely different caliber than those of state.

He shook these thoughts off, resolving to speak with Margherita. Too much lingered between them unsaid, a gulf of silence which threatened to envelop their relationship, and now, Alberto realized, perhaps even their children. Soon he thought, after this. I must comfort Germano now. The boy needs me. With a deep breath, he gently pushed open the door to Germano’s room, stepping in. “Germano? Papa’s here…how are you?” he kept his voice soft. Azzo told him Germano had refused to leave his room since the incident.

The room, Alberto noted, reflected the boy’s state, disheveled, it appeared clear that Germano turned away his servants when they came to clean the place, half-eaten meals littered the floor, the painstakingly composed books Germano was so fond of open and strewn with equal indifference about the room, a film of dust gathering on their pages. Germano himself sat upon his bed, his knees tucked to his chest, rocking gently, a distant glean in his eye. To Alberto’s surprise, he spoke, his words distant and surreal. “Yes. Zeus told me you were coming.”

Alberto arched a quizzical brow, confused at the boy’s speech..”Zeus..?”

Germano replied with a sudden intensity, “Yes father..Zeus…he’s told me the Christian god has him in chains. But he wants you and I to save him.”

Alberto brushed aside these ramblings, “Son. You must never speak so in public or private. There is only one God. Azzo told me about Basso, I am deeply sorry…would you like us to go and get a new dog in the morning?” He felt he was bumbling, incredibly ill at least with his own child.

Germano shook his head vigorously, “No, no, Basso is all right. It’s been explained to me by…others…I don’t need another dog.” A distant, almost eerily empty smile crept across the boys face, to Alberto, he seemed bizarrely content with this pronouncement.

Alberto nodded his head slightly in agreement. The boy remained overwhelmed, and rightly so perhaps, Basso had been his only solace. He seemed to pay little attention to Alberto’s words. He would try again in the morning, he resolved..indeed, he would try every day, as he suddenly realized that he had come to the conclusion that he must remain in Corsica for quite a bit longer than he anticipated before. He spoke briefly to Germano again. “That is well. I will come to see you again tomorrow, son.” He wrapped an arm around the boy, pulling him close for a moment. “I love you Germano,” with that he departed, leaving the boy as he found him. Recently, news reached him which gave him hope for Germano’s future. Elvira de Coimbra, heiress of the duchy of Braganza, had recently been widowed by her husband, her father, a destitute exile from his own father’s court who wandered the Mediterranean seeking handouts, had met with Alberto in Corsica, expressing his willingness to marry the recently eligible Elvira to an Obertenghi. Alberto, mindful that the fact that he even sought out the Pauper Duke revealed the true extent of his need, said that Germano would be eligible. The man hesitated briefly, asked for a larger sum, and agreed. Alberto hoped this would secure a future for Germano- one far from Corsica where his status would matter less. He closed the door gently, turning his thoughts to the next item on his agenda.

He must speak with Margherita…Demetrio’s lecture and discipline must come from a united front, one united as it had not been since his birth. Alberto suspected without his wife, without all of her, no amount of words on his part would repair their son, or their family. He began to walk toward Margherita’s rooms, his steps filled with purpose, hope, and an aching sense of fear, as Alberto could not imagine what recourse he would have if he failed to rouse her to action.

An excellent if not foreboding chapter on the deepening madness ! Can't wait to see the next update !

I must say I'm not sanguine in my hopes for Demetio's future. And poor Germano, I feel more and more sorry for him. Lifes tough being a bastard..

Well I'm back from my weekend away, had fun. In other news, my return means that updates will continue for this AAR, starting immediately. Thanks to everyone for their comments on the last update. Next update will be narrative, to be followed in a day or two by another history book.

EmprorCoopinius: That's an option. I'll be sure to advise Alberto of it.

Canonized Well the wait is over, and yes, sadly, Germano is delving deeper into madness.

EnglishPatriot: You're not the only one not sanguine. But I can tell you that the future of the dynasty rests in his hands.

EmprorCoopinius: That's an option. I'll be sure to advise Alberto of it.

Canonized Well the wait is over, and yes, sadly, Germano is delving deeper into madness.

EnglishPatriot: You're not the only one not sanguine. But I can tell you that the future of the dynasty rests in his hands.

Reunion

Margherita lingered in her chair, her hands crossed gingerly in her lap, listening to the commotion outside. Her husband, it seemed, had arrived and sought an audience. Silvia, her most devoted maid, adamantly refused to admit him. She’d told her maids earlier that she would prefer no interruptions in her sleep, indeed, if she recalled correctly this was a standing order, one she instituted..since..the exact time escaped her, as so many details often did lately, lost amidst the clutter of her mind. Indeed, generally, Alberto did not come to her chambers. He learned some time ago that she would arrive in his during his visits when it suited her and elected not to press the issue, in the same manner that he elected not to press so many similar issues. Ostensibly, this order stood in order to preserve the night for her sleep. The Duchess, she heard the maids whisper, kept odd hours, awaking at noon and staying awake only briefly, retiring shortly after dinner.

In reality, Margherita seldom slept. The long and haunting hours of the night passed as though in a trance for her, unable to sleep, for fear that her demons might find her there. While she stood awake, she could entertain herself with the amusements she requested in her room, from the delicate embroidery she had in the last decade developed such an aptitude for, to reading various authors to while away the hours. Of late, she preferred poetry. The whimsical, if sometimes tragic words of Ovid, Catullus, and others proved for lighter reading than the philosophers, or the devotional prayer books which she sometimes came across. The Moors who last occupied Corsica had possessed an admirable collection of texts, one which the scholarly community of Corsica, albeit small, feasted upon. The poets were lighter stuff, more fanciful and romantic. The Metamorpheses promised her a world entirely divorced from that of Corsica, and she confessed to relishing in it. Occasionally she sent to Azzo for a copy of the Duchy’s ledger sheet, or to request a summary of the ongoing diplomatic affairs of the Kingdom, yet more often than not these reports interested her only briefly, and then she found that they reminded her of times which she would rather forget.

She knew the servants whispered about her, indeed, they whispered louder and louder in the last few years, as they surmised that their mistress might be less inclined to discipline them due to her current state, “A sad case” some remarked, and others “No wonder the Duke spends so much time abroad…he’s married to a ghost.” Though she felt herself piqued at their remarks, and even on occasion resolved to banish a particular one from her service, perhaps even to have one flogged as a testament to the others, she did nothing. No, Margherita could not rouse herself to put forth the requisite effort to sustain any such resolve. She supposed she had her reasons. She thought of it rarely, but she heard Alberto coming and thought she knew the subject of his visit.

Margherita still wept when she thought of Chiano. Though Alberto commanded all relics of his presence, of his very existence even, removed from the keep, and labored anxiously not to speak his name, his memory remained vivid and clear in Margherita’s heart. The bright and innocent eyes, the guileless, exuberant chuckles, the clumsy and endearing way with which he articulated his first words, Mama, beaming at Margherita over him. His death struck her unaware. One day, her son seemed fine, and she shared stories with him of how he would play with his sibling, quickening inside her, the next, he lay cold and dead. She held him them, hoping that her warmth might instill a bit of life into him, but no life remained for Chiano. Alberto tried to comfort her of course, whispering that Chiano and they would be reunited eventually, that they would have more children. Yet to Margherita, the words seemed hollow. Children were not commodities; they could not be replaced with the ease with which one might trade one bushel of wheat for another. Chiano would never again be. His lossdrove home a point Margherita long considered, that of her own futility. Each time she invested herself in someone, they were taken from her. She gave herself to Francesco, and he was taken from her. Yet then she had resolved not to mourn him. She found a deep bond with Alberto, new arms to hold her, yet this had not contented her. She lobbied long and hard for the war with Cagliari, and so her husband departed. They had not had an uninterrupted year together since, Alberto even missed Chiano’s birth, no doubt wallowing in the Sardinian mud when his first born came into this word. And so she lost her husband, as if by her own design. After Cagliari there had been Mallorca, and ever since Alberto seemed more like a visitor each time he returned to Corsica than a native. The Duke of Sardinia and Mallorca’s demesne included a broader scope than Corsica alone. Another loss, Margherita thought, one even more directly attributable to myself. Perhaps though, even this might have been born if Chiano remained. In Chiano, she found the only pure, unselfish happiness she had known in her life, he was a revelation to her, a miracle even. Yet he too went away, along with all the others. Another tragedy.

Perhaps, Margherita thought, the Lord was simply visiting punishment upon those she loved, afflicting her child with her sins. Her lust, her vanity, and her insatiable pride. In any case, in the wake of Chiano’s death Margherita believed she found a solution for the systemic tragedy she felt consumed her. If she removed herself from this life, she thought, no harm could come to her, nor to those she loved. Upon Demetrio’s birth, she had decided to entrust his upbringing to others. She had learned the hardway that her investments in people, however well intended, rarely resulted in any profits. As a girl, she had seen her father cut his losses on many bad deals, firmly instructing failing enterprises dependent upon his support that he could not continue to provide them with financing, or to supply them with products. And so Margherita applied this simple lesson to her life, if she did not engage, then she could not lose. And so she retired to her room, became the subject of servant’s gossip, and a recluse even in her own home. Demetrio and her daughters were she saw in passing, favoring them with smiles. She continued to visit Alberto, though their lovemaking lacked the fervor that their intimacy once lent it, as she believed it her duty. But the quiet moments between them, the inside jokes and the knowing glances of lovers were distant memories now. Indeed, Alberto seemed reluctant to broach the issue, fearful of inducing something far more terrible. She told herself it was all for the best.

She heard Alberto’s firm knock on her door. So formal, she thought..it had not always been so. She thought she knew why he came. Demetrio. Azzo arrived similarly a few days earlier and informed her of grave tones of her son’s actions. The words shocked her, even in her languid state, and she felt a revulsion for both the act and her son, in many ways the most intense feeling she had felt in years, even. Azzo pleaded with her to speak with Demetrio, to impress upon him the gravity of what he had done and to ensure it would not occur again. Yet Margherita, who never in her life had once disciplined Demetrio, could not even fathom what she might say to her son. She knew, vaguely, of his animosity towards Germano, even she could scarcely avoid noticing the venomous looks he tossed at his brother in familial settings. Personally, Alberto’s bastard never bothered her particularly. She, who came to his bed only a month removed from Francesco’s, could not begin to judge the actions of her husband before their union, even as Alberto never sought to discover the status of her virginity. Her interest in the boy himself, who arrived at court in the wake of Chiano’s death, paralleled her interest in all things after that event. Demetrio’s crime frightened her. It suggested her son was a monster, and that perhaps her withdrawal did not have the desired effect…she pushed these thoughts from her mind, determined not to entertain them.

“Come in, Alberto” she spoke softly, as though his knock woke her, rather than any tussle with the staff.

He entered in the spirit of her words, gingerly opening the door and stepping inside, closing it behind him with equal care.

In his mind, he had thought that he would have a speech ready, something spectacular and firey designed to at least provoke her, in the hopes that passion of any kind mind have a contagious effect, yet when Alberto entered, he felt the words crumbling in his mind, whatever he thought of her actions over the last few years, she clearly remained the same woman he married, he thought, as he looked at her. The soft, supple curve of her jaw into her neck, begging to be kissed, the abundant locks of blond hair framing her face, the occasional strand straying into her face. No, Alberto thought, he could be angry with her. He could not yell. Still, he thought, steeling his resolve, he came for a reason.

“Margherita, did you here about Demetrio?” he spoke idly, as if they were discussing a mundane subject, Demetrio’s progress with his tutors, perhaps.

“Yes.” She chose not to elaborate, lacking the words to provide any adequate description of her feelings on the matter.

“Our son needs his parentse Germano is devastated. He needs us Margherita, because we have failed him. I will claim my share of the blame. But he needs both of us to claim our own share.” Alberto spoke gently, careful to emphasize his own fault, but refusing to spare her any blame. He added “Since Chiano, you have changed. I know you mourn him. So do I. But we have more than one son, and today we must think of Demetrio.” It was the first time he had spoken the word Chiano in a decade.

His words stung Margherita, she opened her mouth to reply, but words refused to form. Instead, Margherita felt as though she had suffered another great loss. Not of Chiano, not again, but of Demetrio, the son she never knew nor tried to know. The monster that she nurtured in her womb while she mourned his brother. She realized, suddenly and irrevocably, that her withdrawal had more inflicted more casualties than merely the Alberto’s vanished soft touch and tender gazes. Instead of words, she wept.

Alberto could not formulate a response. As always, her pain seemed vivid to him, and as so often over the last few years, he did not know the proper response. Instinctually, he closed the distance between them, his arms wrapping around her, muffling her sobs. He wondered if she cried for Chiano, or because of his harshness. In any case, he decided his reply must be the same for both and whispered the words into her ear, “I love you.”

The words echoed in Margherita’s ears, and she wrapped her arms around Alberto, drawing him to her. Despite all of it, she thought, despite all of it he still loves me. If he loves me, she thought, there is still hope for us. For all of us. She whispered back “I love you too.”

They remained locked together for a time, each renewed by the other. For Margherita, her losses suddenly seemed to be less substantial than she thought. Perhaps, she recognized, there is another way. Demetrio, she thought, is still young, there is time for healing. Alberto rejoiced in her embrace, in the firmness, the presence he felt in it that he just now realized he had missed so. He moved his lips to hers, pressing them to hers gently and delighted when they vividly pressed back, a sensation he had nearly forgotten in the intervening years.

As they kissed each thought the same thought, that time remained to heal the wounds they had inflicted on their family, to salvage the wreckage and craft a more stable vessel. Yet lingering at the back of their minds remained the distinct fear that at least for Demetrio and Germano, the damage may have passed the point of no return, and the wreckage would be unsalvageable.

Margherita lingered in her chair, her hands crossed gingerly in her lap, listening to the commotion outside. Her husband, it seemed, had arrived and sought an audience. Silvia, her most devoted maid, adamantly refused to admit him. She’d told her maids earlier that she would prefer no interruptions in her sleep, indeed, if she recalled correctly this was a standing order, one she instituted..since..the exact time escaped her, as so many details often did lately, lost amidst the clutter of her mind. Indeed, generally, Alberto did not come to her chambers. He learned some time ago that she would arrive in his during his visits when it suited her and elected not to press the issue, in the same manner that he elected not to press so many similar issues. Ostensibly, this order stood in order to preserve the night for her sleep. The Duchess, she heard the maids whisper, kept odd hours, awaking at noon and staying awake only briefly, retiring shortly after dinner.

In reality, Margherita seldom slept. The long and haunting hours of the night passed as though in a trance for her, unable to sleep, for fear that her demons might find her there. While she stood awake, she could entertain herself with the amusements she requested in her room, from the delicate embroidery she had in the last decade developed such an aptitude for, to reading various authors to while away the hours. Of late, she preferred poetry. The whimsical, if sometimes tragic words of Ovid, Catullus, and others proved for lighter reading than the philosophers, or the devotional prayer books which she sometimes came across. The Moors who last occupied Corsica had possessed an admirable collection of texts, one which the scholarly community of Corsica, albeit small, feasted upon. The poets were lighter stuff, more fanciful and romantic. The Metamorpheses promised her a world entirely divorced from that of Corsica, and she confessed to relishing in it. Occasionally she sent to Azzo for a copy of the Duchy’s ledger sheet, or to request a summary of the ongoing diplomatic affairs of the Kingdom, yet more often than not these reports interested her only briefly, and then she found that they reminded her of times which she would rather forget.

She knew the servants whispered about her, indeed, they whispered louder and louder in the last few years, as they surmised that their mistress might be less inclined to discipline them due to her current state, “A sad case” some remarked, and others “No wonder the Duke spends so much time abroad…he’s married to a ghost.” Though she felt herself piqued at their remarks, and even on occasion resolved to banish a particular one from her service, perhaps even to have one flogged as a testament to the others, she did nothing. No, Margherita could not rouse herself to put forth the requisite effort to sustain any such resolve. She supposed she had her reasons. She thought of it rarely, but she heard Alberto coming and thought she knew the subject of his visit.

Margherita still wept when she thought of Chiano. Though Alberto commanded all relics of his presence, of his very existence even, removed from the keep, and labored anxiously not to speak his name, his memory remained vivid and clear in Margherita’s heart. The bright and innocent eyes, the guileless, exuberant chuckles, the clumsy and endearing way with which he articulated his first words, Mama, beaming at Margherita over him. His death struck her unaware. One day, her son seemed fine, and she shared stories with him of how he would play with his sibling, quickening inside her, the next, he lay cold and dead. She held him them, hoping that her warmth might instill a bit of life into him, but no life remained for Chiano. Alberto tried to comfort her of course, whispering that Chiano and they would be reunited eventually, that they would have more children. Yet to Margherita, the words seemed hollow. Children were not commodities; they could not be replaced with the ease with which one might trade one bushel of wheat for another. Chiano would never again be. His lossdrove home a point Margherita long considered, that of her own futility. Each time she invested herself in someone, they were taken from her. She gave herself to Francesco, and he was taken from her. Yet then she had resolved not to mourn him. She found a deep bond with Alberto, new arms to hold her, yet this had not contented her. She lobbied long and hard for the war with Cagliari, and so her husband departed. They had not had an uninterrupted year together since, Alberto even missed Chiano’s birth, no doubt wallowing in the Sardinian mud when his first born came into this word. And so she lost her husband, as if by her own design. After Cagliari there had been Mallorca, and ever since Alberto seemed more like a visitor each time he returned to Corsica than a native. The Duke of Sardinia and Mallorca’s demesne included a broader scope than Corsica alone. Another loss, Margherita thought, one even more directly attributable to myself. Perhaps though, even this might have been born if Chiano remained. In Chiano, she found the only pure, unselfish happiness she had known in her life, he was a revelation to her, a miracle even. Yet he too went away, along with all the others. Another tragedy.

Perhaps, Margherita thought, the Lord was simply visiting punishment upon those she loved, afflicting her child with her sins. Her lust, her vanity, and her insatiable pride. In any case, in the wake of Chiano’s death Margherita believed she found a solution for the systemic tragedy she felt consumed her. If she removed herself from this life, she thought, no harm could come to her, nor to those she loved. Upon Demetrio’s birth, she had decided to entrust his upbringing to others. She had learned the hardway that her investments in people, however well intended, rarely resulted in any profits. As a girl, she had seen her father cut his losses on many bad deals, firmly instructing failing enterprises dependent upon his support that he could not continue to provide them with financing, or to supply them with products. And so Margherita applied this simple lesson to her life, if she did not engage, then she could not lose. And so she retired to her room, became the subject of servant’s gossip, and a recluse even in her own home. Demetrio and her daughters were she saw in passing, favoring them with smiles. She continued to visit Alberto, though their lovemaking lacked the fervor that their intimacy once lent it, as she believed it her duty. But the quiet moments between them, the inside jokes and the knowing glances of lovers were distant memories now. Indeed, Alberto seemed reluctant to broach the issue, fearful of inducing something far more terrible. She told herself it was all for the best.

She heard Alberto’s firm knock on her door. So formal, she thought..it had not always been so. She thought she knew why he came. Demetrio. Azzo arrived similarly a few days earlier and informed her of grave tones of her son’s actions. The words shocked her, even in her languid state, and she felt a revulsion for both the act and her son, in many ways the most intense feeling she had felt in years, even. Azzo pleaded with her to speak with Demetrio, to impress upon him the gravity of what he had done and to ensure it would not occur again. Yet Margherita, who never in her life had once disciplined Demetrio, could not even fathom what she might say to her son. She knew, vaguely, of his animosity towards Germano, even she could scarcely avoid noticing the venomous looks he tossed at his brother in familial settings. Personally, Alberto’s bastard never bothered her particularly. She, who came to his bed only a month removed from Francesco’s, could not begin to judge the actions of her husband before their union, even as Alberto never sought to discover the status of her virginity. Her interest in the boy himself, who arrived at court in the wake of Chiano’s death, paralleled her interest in all things after that event. Demetrio’s crime frightened her. It suggested her son was a monster, and that perhaps her withdrawal did not have the desired effect…she pushed these thoughts from her mind, determined not to entertain them.

“Come in, Alberto” she spoke softly, as though his knock woke her, rather than any tussle with the staff.

He entered in the spirit of her words, gingerly opening the door and stepping inside, closing it behind him with equal care.

In his mind, he had thought that he would have a speech ready, something spectacular and firey designed to at least provoke her, in the hopes that passion of any kind mind have a contagious effect, yet when Alberto entered, he felt the words crumbling in his mind, whatever he thought of her actions over the last few years, she clearly remained the same woman he married, he thought, as he looked at her. The soft, supple curve of her jaw into her neck, begging to be kissed, the abundant locks of blond hair framing her face, the occasional strand straying into her face. No, Alberto thought, he could be angry with her. He could not yell. Still, he thought, steeling his resolve, he came for a reason.

“Margherita, did you here about Demetrio?” he spoke idly, as if they were discussing a mundane subject, Demetrio’s progress with his tutors, perhaps.

“Yes.” She chose not to elaborate, lacking the words to provide any adequate description of her feelings on the matter.

“Our son needs his parentse Germano is devastated. He needs us Margherita, because we have failed him. I will claim my share of the blame. But he needs both of us to claim our own share.” Alberto spoke gently, careful to emphasize his own fault, but refusing to spare her any blame. He added “Since Chiano, you have changed. I know you mourn him. So do I. But we have more than one son, and today we must think of Demetrio.” It was the first time he had spoken the word Chiano in a decade.

His words stung Margherita, she opened her mouth to reply, but words refused to form. Instead, Margherita felt as though she had suffered another great loss. Not of Chiano, not again, but of Demetrio, the son she never knew nor tried to know. The monster that she nurtured in her womb while she mourned his brother. She realized, suddenly and irrevocably, that her withdrawal had more inflicted more casualties than merely the Alberto’s vanished soft touch and tender gazes. Instead of words, she wept.

Alberto could not formulate a response. As always, her pain seemed vivid to him, and as so often over the last few years, he did not know the proper response. Instinctually, he closed the distance between them, his arms wrapping around her, muffling her sobs. He wondered if she cried for Chiano, or because of his harshness. In any case, he decided his reply must be the same for both and whispered the words into her ear, “I love you.”

The words echoed in Margherita’s ears, and she wrapped her arms around Alberto, drawing him to her. Despite all of it, she thought, despite all of it he still loves me. If he loves me, she thought, there is still hope for us. For all of us. She whispered back “I love you too.”

They remained locked together for a time, each renewed by the other. For Margherita, her losses suddenly seemed to be less substantial than she thought. Perhaps, she recognized, there is another way. Demetrio, she thought, is still young, there is time for healing. Alberto rejoiced in her embrace, in the firmness, the presence he felt in it that he just now realized he had missed so. He moved his lips to hers, pressing them to hers gently and delighted when they vividly pressed back, a sensation he had nearly forgotten in the intervening years.

As they kissed each thought the same thought, that time remained to heal the wounds they had inflicted on their family, to salvage the wreckage and craft a more stable vessel. Yet lingering at the back of their minds remained the distinct fear that at least for Demetrio and Germano, the damage may have passed the point of no return, and the wreckage would be unsalvageable.

Very nicely crafted, a mix of both good and bad which is so like real life and so often lacking in fiction of any sort. Excellent update as always.

Very good dive into the two of them and the mad sadness that came afterward . The hope and pessimism mixed at the end makes for a poignant chapter !

Hmm, I think the end speaks for itself, things won't end well for Demetrio and Germano, Great read!

Well I was going to update today, but photobucket, which I use for image hosting, is down. As you can guess from the fact that there are images to host, the next update will be another history book installment covering the last part of Alberto's reign, his children's marriages, etc. So I'll get that up when photobucket comes back, hopefully by tomorrow. I've got the screenshots and everything else for it done. While you're waiting I'll give some feedback.

EmprorCoopinius: Thanks, I try to give it a realistic twist- as I don't think you can always make everything better.

Canonized: A little bit of both, yes, I'm glad you liked it. The next ruler, Demetrio, will hopefully bring even more contrasts into the mix.

Triv:I appreciate the compliment, though I assure you my skills are quite limited.

EnglishPatriot: It's hard for things to end well when you're an excommunicated schizephrenic/insane heretic bastard (Germano)..but I'll leave Demetrio's fate open for now.

As always, I appreciate the comments and will get the next update up as soon as photobucket cooperates.

EmprorCoopinius: Thanks, I try to give it a realistic twist- as I don't think you can always make everything better.

Canonized: A little bit of both, yes, I'm glad you liked it. The next ruler, Demetrio, will hopefully bring even more contrasts into the mix.

Triv:I appreciate the compliment, though I assure you my skills are quite limited.

EnglishPatriot: It's hard for things to end well when you're an excommunicated schizephrenic/insane heretic bastard (Germano)..but I'll leave Demetrio's fate open for now.

As always, I appreciate the comments and will get the next update up as soon as photobucket cooperates.

JimboIX said:EnglishPatriot: It's hard for things to end well when you're an excommunicated schizephrenic/insane heretic bastard (Germano)..but I'll leave Demetrio's fate open for now. .

Good God!, I didn't realise it could go so bad for Germano, poor guy..

I`ve finally catched up and - wow! I`m yet again shocked by refined story made by roleplaying in-game traits and events, with realism and psychological depth. Together with 2-perspective history-book bonuses it creates great combo. Looking forward to next chapters - something tells me that if Demetrio would became next Duke, he will be overambitious man-to-bring-disaster  .

.

Great work, If I ever finish my megacampaign, I`ll try your format in next AAR - of course if my English, and writing skills improve

Great work, If I ever finish my megacampaign, I`ll try your format in next AAR - of course if my English, and writing skills improve

Alberto's reign, part III

By contemporary standards, the campaign against Mallorca paled in comparison to other crusades prosecuted against the infidel in the years after the declaration of the first Crusade against Tunis, which it must be noted continued even as Alberto’s armies converged upon the two Islands. Indeed, the least of the Dukes of our empire could likely muster as great a force. Details of the campaign are somewhat scarce, the Emir of Mallorca, who made his residence in the mainland of Iberia, deriving only his title from the Islands, expended little effort in their defense, the entirety of his force consumed in contesting the possession of Murcia from the Archbishop of Francia, Alberto’s undeclared ally in the endeavor who invested and ultimately conquered his Iberian possessions. Upon setting foot upon the beaches of Mallorca, Alberto is said to have declared to the Mallorcans only that, “We are Islanders alike; I come only to liberate you from your absentee lords. Too well do I know the scorn of the mainland. Of that disdain, you shall have none from me.” Indeed, although the predominant faith of the Mallorcans did not mirror Alberto’s, little strife existed between Infidel and Christian during Alberto’s reign, with open revolt following only after the accession of Demetrio, who took a dimmer view of heresy and ultimately compelled their submission to the one true faith. After a brief campaign of six months, Alberto succeeded in conquering Mallorca and Menorca alike, declaring himself now Duke of Sardinia and Mallorca.

The newly conquered islands

Despite the double duchy which he now proclaimed himself master of, the international community looked upon Alberto’s accession with contempt, the King of Naples remarking to an ambassador who compared the conquest of Mallorca to the King’s own conquest of Sicily that “The Obertenghi’s have a gift for conquering undefended provinces. We Normans, however, prefer a bit of sport with our enemy, and Islands worth owning” the ambassador, sent to negotiate a marriage between Demetrio and the King’s youngest daughter, found himself summarily dismissed from court, his offer coolly rebuffed.

In the years following the proclamation of the dual duchy, the new double Duke Alberto busied himself with the maintenance of his realm. The wars took a disastrous toll upon the finances of the duchy, the cost of transporting the army to Mallorca and then to Menorca eradicated the treasury. and Alberto strove to render the Duchy solvent again. In these efforts, true to his word on the beaches of Mallorca he refrained from discriminating or withholding funds from the newly conquered territories, indeed, Mallorca almost immediately became the driving engine of the economy, it’s income double that of Corsica’s. Alberto traveled extensively, often visiting vassals in person to negotiate tribute, Mariano, the Count of Arborea, once a lukewarm vassal, became steadfast in his devotion. Gradually, sawmills, fisheries, and other industries blossomed in the islands, bringing with them a new found prosperity.

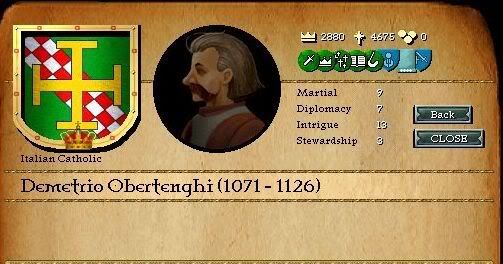

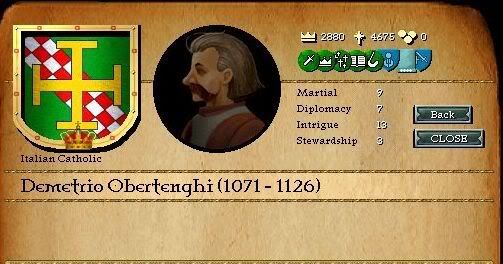

Alberto became concerned with his legacy as well, he grew on in years, and following the death of Chiano Margherita, who during this decade is sometimes rumored to have been mad or at least profoundly depressed by official reports, bore him only one son, Demetrio, with three daughters following. Alberto’s bastard, Germano, lacked the prestige to declare himself legitimate, and ultimately even the soundness of mind necessary to formulate the thought, though this did not become clear until later in his life. Of Demetrio’s character in youth much has been remarked, although a thorough investigation of the record reveals that much of the evidence commonly associated with heirs, from tutors correspondence to priest’s remarks on their piety, seems to have been subsequently culled from the record, an act many attribute to Demetrio himself. The most famous, if perhaps apocryphal, tale, involves his cruelty to animals. A legend amongst Corsica villagers, though it can not be verified, suggests that Demetrio feasted upon dogs, cats, and even children in the royal keep, until the hand of God touched him and encouraged him to turn his rage against the infidels. Though this tale clearly suffers from the embellishment of centuries, a bit of murkiness does surround Demetrio, a shadow his defenders, especially those in the church who defer to his subsequent canonization, struggle with.

Demetrio Obertenghi

Shortly after Demetrio’s ninth birthday, Alberto began to spend a great deal more time in Corsica, and ultimately decided to raise his children himself. The reasons for this decision are unknown, though gossip suggests it coincided with Margherita’s belated recovery from a malaise which infected her after Chiano’s death. In addition, during this time, long after another child was looked for; Margherita conceived for a final time and bore Alberto a final child, and another son, whom they named Vittorio, in belated celebration for Alberto’s conquest of Mallorca. Alberto raised Vittorio from birth, although he did not live to see his youngest son reach his majority.

Vittorio Obertenghi

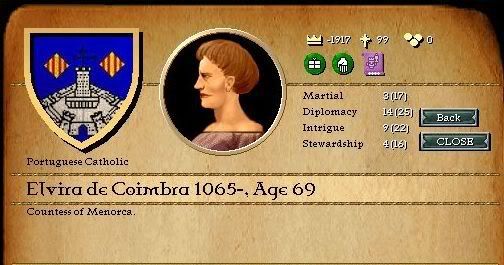

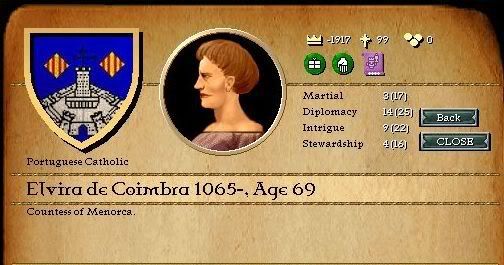

In an effort to legitimize Germano, Alberto succeeded in arranging his marriage to Elvira de Coimbra. This marriage reflects his burgeoning interest in Iberia, fueled by his Mallorcan conquest. Elvira de Coimbra’s chief significance was that she was the heiress of the Duchy of Braganza. Widely remarked upon as a coup even by those who professed to respect the grasping Alberto little, this marriage gave ensured that any potential children of Germano would stand to inherit the Duchy of Branganza, and bring it into the Obertenghi’s ever expanding sphere of influence. Although some considered this a coup, as Alberto seemed to succeed in marrying his bastard to a woman far beyond his own station, others insisted that this reflected only the desperation of Elvira’s father, a deposed exile shunned by his more powerful in-laws, whose previous arranged marriage for Elvira proved disastrous when her husband died of pneumonia a mere three years into their union, and without producing an heir. In an effort to further legitimize Germano, Alberto granted him the County of Menorca upon the occasion of his wedding, despie his recent excommunication, carried out by the Pope in retaliation for Alberto’s failure to join the Tunisian crusade despite his proximity and prompted by rumors of Germano’s heresy.

Elvira de Coimbra

Indeed, although few records attest to Demetrio’s youth, numerous documents purport to Germano’s heresy and madness. Upon his arrival in Menorca he insisted upon speaking solely in the Greek tongue, and insisted upon making his residence upon the highest promonotory of the Island, declaring it Olympus, where he would patiently await communication from Zeus, with whom he claimed to converse regularly. Alberto, in Corsicsa, gave little credence to these rumors while he lived. This regrettable indulgence of his heresy on Alberto’s part does little to recommend him to the church. Many of these accounts have long been suggested to have been the work of Demetrio, whose relationship with Germano suffered, it is thought, from Alberto’s attempts to legitimize Germano, which Demetrio perceived as a threat to his rights as heir. In any case, Germano evidently attended little to his wife, as they failed to produce any children over the course of their seven year marriage. Upon his death at twenty three, his brother, in a gesture of magnamity, granted Menorca to his widow, who contemporaries suggest actually ruled Menorca during Germano’s tenure as Count. Elvira de Coimbra ultimately outlived both brothers, surviving to the age of seventy seven, perishing in the reign of Demetrio’s grandson, St. Gaimar. Braganza itself ultimately passed through the line of her younger sister’s children.

While Alberto’s efforts to legitimize Germano and annex Braganza ultimately proved fruitless, the marriage he arranged for Demetrio ultimately resulted in a profound effect on the history of the duchy. Alberto, thinking that he secured his dynasty a future in Iberia, sought to secure a similar foundation in Italy by wedding Demetrio to Hunila of Salerno, the only daughter of Gisulf II of Salerno.

Hunila of Salerno

Although Gisulf possessed two healthy sons and few viewed Hunila as an heiress, the alignment of Corsica and Salerno presented a united Western front to combat any further Norman expansion. Pessimists remarked that Alberto, the descendent of Lombard princes, and Gisulf, the last of the Lombard princes, were simply uniting by blood the last remnants of a futile people, one which hardly threatened to combat the ascendancy of the Normans in the region, whose successes in Sicily were coupled with expansion northward, into Urbino. Indeed, many point to the origins of enduring strife between Sicily and the Obertenghi in this marriage.

Salerno, surrounded by enemies

Shortly after Alberto announced this arrangement, an interesting offer approached him from the newly ensconced King of France, Guillaume d’Aquitaine, sometimes called the Usurper. The crusade against Tunisia drained France, its chief champion, weakening the Capetian King’s purse, indeed, despite a campaign of over a decade Tunis remained in the defiant hands of the King of Zirids, who even succeeded in snatching a few French provinces, if temporarily, from the hands of French lords. In addition, the successful gains of France in Tunisia were largely attributable to the Archbishop of Francia’s leadership, which assured that lands which were conquered did not become available for redistribution by the King, further weakening his position. Guillaume d’Aquitaine, the most powerful of the French dukes, sensing the exhaustion of the French people in their crown and their King, proclaimed the King unfit to rule in the wake of the Zirid conquest of Toulouse, and declared war upon the embattled Phillipe, whose exhausted armies put up little fight as the Guillaume stormed Paris. Proclaiming himself King by right of Conquest, Guillaume won over the conquering Archbishop of Francia, who crowned him King in Rheims. The Capetians were reduced to mere Dukes of Orleans. Although Guillaume succeeded in wresting the Crown from Phillipe, the war against the Zirids persisted, and after successfully expelling the infidel from France itself, he sought to take the war to Tunisia itself, to fulfill the crusade. Seeking local allies, the Archbishop of Francia persuaded him to contact Alberto, whose conduct in the Mallorcan war impressed him, and the Archbishop saw as a useful counterweight to the growing strength of Sicily. The Usurper’s offer to Alberto was to join him in the holy crusade and march of Tunisia, where the French King promised that the renewed armies of his Kingdom combined with Alberto’s would triumph over the Zirids. Most enticing of all, he assured Alberto that he himself had no permanent interests in the area, and would allow the provinces of the Zirid’s to be occupied in the name of the Duchy of Mallorca and Sardinia.

King Guillaume I of France, the Usurper

Alberto, always cautious and well aware of the enduring power of the Zirid’s against nations far greater than his own such as France, England, and Sicily, consulted with his wife and Azzo Terzi. Legend has it that these three deliberated for days before a consensus formed whereby Alberto, declaring that like his Grandfather Obert, he too would crusade against the Infidels, commanded a grand mobilization of the Duchy’s and ventured to Tunisia. Demetrio, recently wed, responded first to the mobilization, raising his own regiment of Cagliari and proclaiming the crusade as well.

In addition, shortly before departing, Alberto entrusted his final will Azzo Terzi. Along with placing in Terzi’s hands the stewardship of this important document, Alberto rewarded the man with the hand of his eldest daughter Adelasia in marriage, a move which shocked many who considered the daughter of even a pauper Duke a prize quite beyond any that the low-born Terzi could aspire to. In any case, this marriage laid the foundation of the Terzi dynasty.

Adelasia Obertenghi, wife of Azzo Terzi

With affairs at home yet again in the capable hands of Terzi, Alberto set sail on his final campaign directly to Tunis, as he believed that only a direct assault upon the object of the crusade would succeed, as the French had proved thoroughly in previous efforts that the conquest of outlying territories accomplished little.

Commentary by Harun Obertenghi

In this portion of the Lives Pandulf sets the tone for the first of many dynamic relationships between siblings, particularly brothers, which in popular culture has long been portrayed as the hereditary bane of the Obertenghis. In this particular instance, however, the context in which Pandulf first attempts to portray a dynamic of sibling rivalry between Germano and Demetrio, bears a little explanation. Pandulf, writing at the beginning of the fifteenth century it must be remembered, was only a century and a half removed from the conflagration of the Brother’s War, the great civil war and dynastic struggle between two sons of House Obertenghi that so dominated the thirteenth century. The paradigm of Obertenghi brothers and their feuds was very much alive and vibrant at the time of his writing, and Pandulf’s affinity for it seems apparent in this chapter. Therefore, any attempts to inject a vein of rivalry into the narrative at such an early stage must be viewed with a jaundiced eye in light of the contemporary historiography of Pandulf’s time. That said, that Demetrio, a man subsequently canonized by the Church, and Germano, his bastard excommunicated brother, did not get along must not shock us either, particularly given Alberto’s attempts to legitimize him in order to provide his nascent dynasty with additional heirs, a move which it seems would naturally arouse resentment in his legitimate heir.

Over the years, many psychiatrists have speculated about what ailment troubled Germano. Although contemporary accounts, and even Pandulf, claim that Germano claimed to here voices, such as Zeus, the temptation to label Germano as a medieval schizophrenic must be resisted however as no diagnosis of a man dead nearly nine hundred years can ever hope to be accurate, indeed, Germano’s voices might have under different circumstances have rendered him a Saint, and the veracity of any such secondhand accounts is questionable. However, it is true that the remains of a Villa from the late eleventh century have been discovered by archeologists at Monte Toro, Menorca’s highest point, suggesting that at least this part of Germano’s tale may have a ring of truth to it, though none of the artifacts recovered attest to the place going by the name Olympus.

The Reign of Alberto, Part III

A portrait of Adelasia Obertenghi, Alberto's eldest daughter

A portrait of Adelasia Obertenghi, Alberto's eldest daughter

By contemporary standards, the campaign against Mallorca paled in comparison to other crusades prosecuted against the infidel in the years after the declaration of the first Crusade against Tunis, which it must be noted continued even as Alberto’s armies converged upon the two Islands. Indeed, the least of the Dukes of our empire could likely muster as great a force. Details of the campaign are somewhat scarce, the Emir of Mallorca, who made his residence in the mainland of Iberia, deriving only his title from the Islands, expended little effort in their defense, the entirety of his force consumed in contesting the possession of Murcia from the Archbishop of Francia, Alberto’s undeclared ally in the endeavor who invested and ultimately conquered his Iberian possessions. Upon setting foot upon the beaches of Mallorca, Alberto is said to have declared to the Mallorcans only that, “We are Islanders alike; I come only to liberate you from your absentee lords. Too well do I know the scorn of the mainland. Of that disdain, you shall have none from me.” Indeed, although the predominant faith of the Mallorcans did not mirror Alberto’s, little strife existed between Infidel and Christian during Alberto’s reign, with open revolt following only after the accession of Demetrio, who took a dimmer view of heresy and ultimately compelled their submission to the one true faith. After a brief campaign of six months, Alberto succeeded in conquering Mallorca and Menorca alike, declaring himself now Duke of Sardinia and Mallorca.

The newly conquered islands

Despite the double duchy which he now proclaimed himself master of, the international community looked upon Alberto’s accession with contempt, the King of Naples remarking to an ambassador who compared the conquest of Mallorca to the King’s own conquest of Sicily that “The Obertenghi’s have a gift for conquering undefended provinces. We Normans, however, prefer a bit of sport with our enemy, and Islands worth owning” the ambassador, sent to negotiate a marriage between Demetrio and the King’s youngest daughter, found himself summarily dismissed from court, his offer coolly rebuffed.

In the years following the proclamation of the dual duchy, the new double Duke Alberto busied himself with the maintenance of his realm. The wars took a disastrous toll upon the finances of the duchy, the cost of transporting the army to Mallorca and then to Menorca eradicated the treasury. and Alberto strove to render the Duchy solvent again. In these efforts, true to his word on the beaches of Mallorca he refrained from discriminating or withholding funds from the newly conquered territories, indeed, Mallorca almost immediately became the driving engine of the economy, it’s income double that of Corsica’s. Alberto traveled extensively, often visiting vassals in person to negotiate tribute, Mariano, the Count of Arborea, once a lukewarm vassal, became steadfast in his devotion. Gradually, sawmills, fisheries, and other industries blossomed in the islands, bringing with them a new found prosperity.

Alberto became concerned with his legacy as well, he grew on in years, and following the death of Chiano Margherita, who during this decade is sometimes rumored to have been mad or at least profoundly depressed by official reports, bore him only one son, Demetrio, with three daughters following. Alberto’s bastard, Germano, lacked the prestige to declare himself legitimate, and ultimately even the soundness of mind necessary to formulate the thought, though this did not become clear until later in his life. Of Demetrio’s character in youth much has been remarked, although a thorough investigation of the record reveals that much of the evidence commonly associated with heirs, from tutors correspondence to priest’s remarks on their piety, seems to have been subsequently culled from the record, an act many attribute to Demetrio himself. The most famous, if perhaps apocryphal, tale, involves his cruelty to animals. A legend amongst Corsica villagers, though it can not be verified, suggests that Demetrio feasted upon dogs, cats, and even children in the royal keep, until the hand of God touched him and encouraged him to turn his rage against the infidels. Though this tale clearly suffers from the embellishment of centuries, a bit of murkiness does surround Demetrio, a shadow his defenders, especially those in the church who defer to his subsequent canonization, struggle with.

Demetrio Obertenghi

Shortly after Demetrio’s ninth birthday, Alberto began to spend a great deal more time in Corsica, and ultimately decided to raise his children himself. The reasons for this decision are unknown, though gossip suggests it coincided with Margherita’s belated recovery from a malaise which infected her after Chiano’s death. In addition, during this time, long after another child was looked for; Margherita conceived for a final time and bore Alberto a final child, and another son, whom they named Vittorio, in belated celebration for Alberto’s conquest of Mallorca. Alberto raised Vittorio from birth, although he did not live to see his youngest son reach his majority.

Vittorio Obertenghi

In an effort to legitimize Germano, Alberto succeeded in arranging his marriage to Elvira de Coimbra. This marriage reflects his burgeoning interest in Iberia, fueled by his Mallorcan conquest. Elvira de Coimbra’s chief significance was that she was the heiress of the Duchy of Braganza. Widely remarked upon as a coup even by those who professed to respect the grasping Alberto little, this marriage gave ensured that any potential children of Germano would stand to inherit the Duchy of Branganza, and bring it into the Obertenghi’s ever expanding sphere of influence. Although some considered this a coup, as Alberto seemed to succeed in marrying his bastard to a woman far beyond his own station, others insisted that this reflected only the desperation of Elvira’s father, a deposed exile shunned by his more powerful in-laws, whose previous arranged marriage for Elvira proved disastrous when her husband died of pneumonia a mere three years into their union, and without producing an heir. In an effort to further legitimize Germano, Alberto granted him the County of Menorca upon the occasion of his wedding, despie his recent excommunication, carried out by the Pope in retaliation for Alberto’s failure to join the Tunisian crusade despite his proximity and prompted by rumors of Germano’s heresy.

Elvira de Coimbra

Indeed, although few records attest to Demetrio’s youth, numerous documents purport to Germano’s heresy and madness. Upon his arrival in Menorca he insisted upon speaking solely in the Greek tongue, and insisted upon making his residence upon the highest promonotory of the Island, declaring it Olympus, where he would patiently await communication from Zeus, with whom he claimed to converse regularly. Alberto, in Corsicsa, gave little credence to these rumors while he lived. This regrettable indulgence of his heresy on Alberto’s part does little to recommend him to the church. Many of these accounts have long been suggested to have been the work of Demetrio, whose relationship with Germano suffered, it is thought, from Alberto’s attempts to legitimize Germano, which Demetrio perceived as a threat to his rights as heir. In any case, Germano evidently attended little to his wife, as they failed to produce any children over the course of their seven year marriage. Upon his death at twenty three, his brother, in a gesture of magnamity, granted Menorca to his widow, who contemporaries suggest actually ruled Menorca during Germano’s tenure as Count. Elvira de Coimbra ultimately outlived both brothers, surviving to the age of seventy seven, perishing in the reign of Demetrio’s grandson, St. Gaimar. Braganza itself ultimately passed through the line of her younger sister’s children.

While Alberto’s efforts to legitimize Germano and annex Braganza ultimately proved fruitless, the marriage he arranged for Demetrio ultimately resulted in a profound effect on the history of the duchy. Alberto, thinking that he secured his dynasty a future in Iberia, sought to secure a similar foundation in Italy by wedding Demetrio to Hunila of Salerno, the only daughter of Gisulf II of Salerno.

Hunila of Salerno

Although Gisulf possessed two healthy sons and few viewed Hunila as an heiress, the alignment of Corsica and Salerno presented a united Western front to combat any further Norman expansion. Pessimists remarked that Alberto, the descendent of Lombard princes, and Gisulf, the last of the Lombard princes, were simply uniting by blood the last remnants of a futile people, one which hardly threatened to combat the ascendancy of the Normans in the region, whose successes in Sicily were coupled with expansion northward, into Urbino. Indeed, many point to the origins of enduring strife between Sicily and the Obertenghi in this marriage.

Salerno, surrounded by enemies

Shortly after Alberto announced this arrangement, an interesting offer approached him from the newly ensconced King of France, Guillaume d’Aquitaine, sometimes called the Usurper. The crusade against Tunisia drained France, its chief champion, weakening the Capetian King’s purse, indeed, despite a campaign of over a decade Tunis remained in the defiant hands of the King of Zirids, who even succeeded in snatching a few French provinces, if temporarily, from the hands of French lords. In addition, the successful gains of France in Tunisia were largely attributable to the Archbishop of Francia’s leadership, which assured that lands which were conquered did not become available for redistribution by the King, further weakening his position. Guillaume d’Aquitaine, the most powerful of the French dukes, sensing the exhaustion of the French people in their crown and their King, proclaimed the King unfit to rule in the wake of the Zirid conquest of Toulouse, and declared war upon the embattled Phillipe, whose exhausted armies put up little fight as the Guillaume stormed Paris. Proclaiming himself King by right of Conquest, Guillaume won over the conquering Archbishop of Francia, who crowned him King in Rheims. The Capetians were reduced to mere Dukes of Orleans. Although Guillaume succeeded in wresting the Crown from Phillipe, the war against the Zirids persisted, and after successfully expelling the infidel from France itself, he sought to take the war to Tunisia itself, to fulfill the crusade. Seeking local allies, the Archbishop of Francia persuaded him to contact Alberto, whose conduct in the Mallorcan war impressed him, and the Archbishop saw as a useful counterweight to the growing strength of Sicily. The Usurper’s offer to Alberto was to join him in the holy crusade and march of Tunisia, where the French King promised that the renewed armies of his Kingdom combined with Alberto’s would triumph over the Zirids. Most enticing of all, he assured Alberto that he himself had no permanent interests in the area, and would allow the provinces of the Zirid’s to be occupied in the name of the Duchy of Mallorca and Sardinia.

King Guillaume I of France, the Usurper

Alberto, always cautious and well aware of the enduring power of the Zirid’s against nations far greater than his own such as France, England, and Sicily, consulted with his wife and Azzo Terzi. Legend has it that these three deliberated for days before a consensus formed whereby Alberto, declaring that like his Grandfather Obert, he too would crusade against the Infidels, commanded a grand mobilization of the Duchy’s and ventured to Tunisia. Demetrio, recently wed, responded first to the mobilization, raising his own regiment of Cagliari and proclaiming the crusade as well.