VI. The Grey King

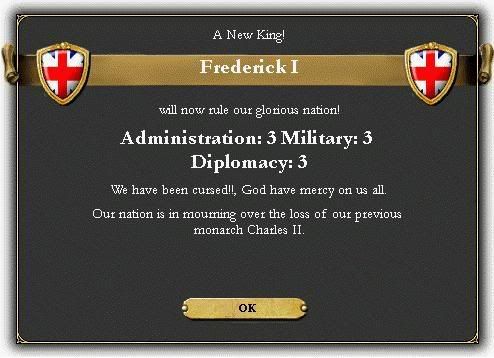

Whatever successes Charles II had had, his own son was not one of them. It was not for the lack of trying; for his time, Charles was an exemplary father who spent most Sundays with his family. His four daughters all led happy, successful lives, but the son who became Frederick I was an unfortunate exception.

Frederick I was a very unpopular king

Frederick I was a cold, distant man who spent his days alone in his chambers. He preferred to spend his morning reading and his afternoon working out problems, with mass precisely at ten o'clock, tea at one and supper at five. Even as a child he grew angry whenever this schedule was upset, and he did not grow out of it despite the best his tutors did. He wrote extensively in his journals, even obsessively, and it is from these scribbled writings that modern historians have been able to piece together details of the so-called Grey King's life. (Frederick's will asked that his journals be destroyed, and his butler proceeded to burn the first three books before reading one, then realized the importance of the books and saved the remainder from the fire)

Frederick rarely smiled and was never on a first-name basis with anyone, even his own wife. His marriage to Mathilda of Brittany was arranged when he was thirteen and she ten and the marriage consummated five years later. It was a political marriage but not an unkind one; his father's own arranged marriage had been a happy one and Charles did his best to find suitable spouses for his children. It was not a happy marriage for either Frederick or Mathilda.

Frederick treated Mathilda as coldly as he treated everyone else. The couple spent long years barren before God gifted them with child. The queen was said to have been a rare beauty and a kind woman whose smile could light up the room, and she was one of the few who was able to calm Frederick down during his rages. Despite this, as soon as he had sired an heir Frederick grew even colder towards his wife. By the time he was crowned high king of the United Kingdoms the two spent nearly all of their time apart and Mathilda was reported to have been on her third affair with Frederick's tacit permission. Although he was cold, Frederick was not a cruel man, and from his diaries it is evident that he realized the duties of a husband and was relieved to be able to pawn them off on other men.

Frederick's journals show him to have been honestly perplexed by the people around him. He was not unkind, but his thoughts rarely turned to anyone else unless it was brought to his attention. Even when he tried to be kind, Frederick ended up being awkward at best, and his clumsy efforts failed to win the loyalty of his subjects as his father had done so easily. Another man might have won the sympathy of the court, but Frederick grew frustrated quickly with others and his bouts of temper were legend.

From our modern perspective it seems obvious that Frederick suffered from some form of autism. It explains the obsessions, the daily rituals, the lack of empathy for others and his general inability to understand people. During his own reign, however, Frederick was variously called 'the Cruel,' 'the Tyrant', or more often in his hearing, 'the Grey King'. Frederick himself did not seem to care what his people thought of him, but his ministers did their best to keep public opinion from becoming seditious.

Although few living could remember the reign of Henry VI there were some who began to muse that the House was cursed. Since actual criticism of the king was treason a number of scandalous songs circulated around London that were most likely veiled mockery of his court. Some of these were later collected in

Mother Goose's Nursery Rhymes (possibly named after a real woman who lived in Boston in the 1660s, supposedly the real wife of Isaac Goose, who went to live with her eldest daughter and sang the rhymes to her grandchildren all day. Her son-in-law gathered them together and published them). Many of these rhymes are still popular with children today, but few understand the meaning behind the words. Two famous rhymes in particular may refer to Frederick:

Master Fred and

Little Maud.

Master Fred

Master Fred, Master Fred

Offered me his ring

So I said, So I said

Not if you were king!

Cole's Notes: This rhyme is often sung by girls today while jumping rope. The first reported use of this rhyme was in the late 16th century, several decades after Frederick's death, and for this reason it is uncertain whether it refers to king Frederick or, as others have suggested, it is a slang phrase for a cripple. Those who believe that Master Fred refers to the king himself believe it to be a veiled reference to his unhappy marriage to Mathilda of Brittany.

Little Maud

Maud was a happy lass

Danced with boys day and night

Her father locked her in her room

And said "She's mine, by right!"

Cole's Notes: Little Maud is usually considered to be a reference to Queen Maud of Scotland, but it is unlikely that she was well-known in England. Instead, scholars are more certain that Maud actually refers to Mathilda de Bretagne. Again, the theme is her marriage to Frederick, but it is clear from his diaries that he did not keep her locked up; it is likely to have been written by his enemies.

The English Renaissance

The first years of Frederick's reign were calm. He had little interest in politics and allowed the court to govern in his name. As time passed, however, Charles' carefully cultivated court began to fall apart. Frederick was rarely present and when he was, his rages and dispassionate isolation did little to stop the haemorraging of talented men from court. The Grey King hated being taken away from his studies and delegated as much as he could to others. If he hoped for peace and quiet, however, he was soundly disappointed.

Without the king to center it the court became unbalanced and courtiers sought power by making requests of. The famously reclusive king was prone to anger when disturbed and several powerful men were banished from court after they made one too many demands on his time. The Italian Vivaldi, one of Charles' favorites, left England in a huff, and Frederick replaced him with Henry Cumberland, a scientist whose book 'On Variables' Frederick had read several times. Similarly, in 1508 Admiral Hawke tendered his resignation after an argument with the king. Much to Hawke's surprise, the king accepted it and replaced him with Thomas Bereford, a talented man who took over much of Frederick's day-to-day duties at court. Bereford was a noticeable improvement from the first two years of the king's rule.

Within two years, Frederick's court was dramatically different from his father's

Frederick was a more rational man than his idealistic father and instituted a number of changes. He cut off aid to the colony of New England, citing figures that showed the colony was a drain on the royal treasury. He also sent the bulk of the army to Brittany to preempt a French invasion of the new duchy and ceased the shipbuilding programs his father had implemented, believing the navy was large enough to defend Britain as it was. An avid reader, he invited a number of scholars to London where he subsidized the publishing of their work in Latin.

The first half of Frederick's reign is often called the

English Renaissance, a decade of rapid cultural and intellectual development. Many continental innovations came to the kingdoms in these years, especially in areas of jurisprudence, law, economics and the natural sciences. At the same time the country experienced a religious revival and many of its most beautiful cathedrals were built in the 1510s. Frederick's largess ensured that the Lancasters would be remembered for their contribution to the arts rather than their madness. His diaries reveal a somewhat less flattering portrait: Frederick believed that the crown needed prestige and, unlike his father, knew few ways to earn it. The chance to keep the prestige his father had left him was one he snatched at. It was, perhaps, a better understanding of his nature than most rulers are capable of.

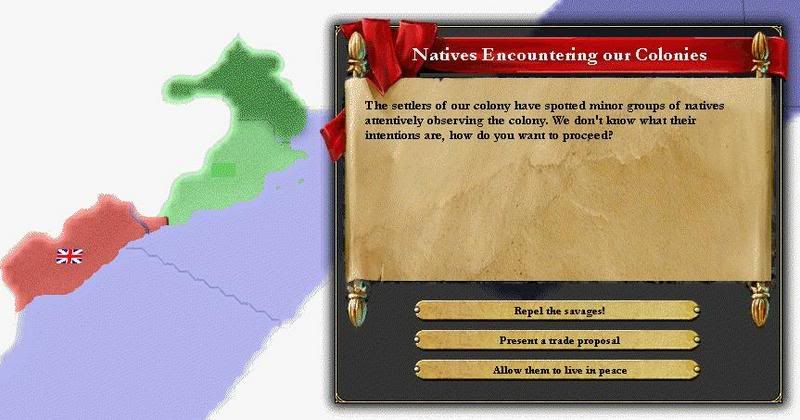

Frederick spent most of his reign ignoring the colonies, but the opposite is not true. In 1511 natives encountered the New England colony and tentative contacts were made. When news reached London Frederick ignored the news; thankfully, his ministers did not. Bereford authorized the created of a New England Company to begin trading with them. The company did not show a profit in Frederick's lifetime, but it eventually proved a sound investment.

Many different proposals were considered to deal with the natives before trade won out

The natives called themselves the Powhatan, and they invited the Company into their territory in 1518 when they set up trading posts. This was to prove crucial later on, but other events had caught Europe's attention in the meantime.

"A Few Acres of Land"

Despite the flurry of events going on in London, the Kingdoms were enjoying a remarkable period of peace and prosperity. The war with France was long over and although the large army was costly, it had successfully prevented another war in the Continent. Knowledge and the arts were flourishing.

This idyllic period came to an abrupt end in 1509 precisely because of this new knowledge. Frederick had commissioned a new map of the Kingdoms using a more precise measurement technique developed in Milan. While studying the new map, he noticed something unusual. The United Kingdoms of the English and Celts did not, in fact, include all the Celts. Some were still under the rule of foreign powers.

Charles II had deliberately left the Orkneys alone. The tiny islands off the coast of Scotland were sparsely populated, settled by Highlanders but owned by Norway. Although they were part of his proposed United Kingdoms, the Norwegians were staunch allies of France. According to local legend, Charles decided "

A few acres of land...are not worth the blood of Englishmen." (

Charles II, Act 3, Scene 2, 34-36) His son did not disagree - but he believed he could strike a bargain for the islands.

Ironically, Frederick's decision was not based on idealism at all. His diaries reveal both a cold, calculating mind and a strange obsession over owning all the British isles. Once he had decided that this anomoly must cease, Frederick decided upon a plan of attack to wrest the islands from their owners. As it turns out, the timing was apt.

Over the previous decade Norway had been absorbed into the kingdom of Denmark through inheritance, making it the undisputed power of the Baltic. Sweden had been weakened by the Muscovian invasion, and Denmark was fighting a long but successful war against its now-weakened rival. Like one scavenger feeding on another, Frederick eyed Scandinavia until he deemed the moment right, then pounced. He ordered the fleet to the Baltic sea, where they blockaded the Sound after a short and decisive battle that left Copenhagen vulnerable to an amphibious invasion. While most of the Danish troops were stranded in Norway, the fleet disgorged troops into Denmark proper. Within six weeks half of Denmark was under siege, and in one master stroke the war was decided.

The Burke Plan comes to fruition

On February 7, 1509, Cophenhagen fell, and the Danish capital was brutally sacked by the British, with Christian IV taken prisoner. Witnessing the destruction, the British general committed suicide a week later. One of the old guard, he had been appalled at Frederick's strategy and, with the Sack of Copenhagen, at the cruelty inflicted on the Danes. Frederick left the position open, further reducing the morale of the troops. Meanwhile, the Sack would reduce Denmark's prestige for a generation.

The Danes proved stubborn, however, and infuriated by their refusal to hand over the Orkneys, Frederick broadened the war. With the fall of Copenhagen, thousands of British troops were freed up to invade Mecklemburg, a Danish ally that had been under blockade since the war began. In June 1510, British troops crossed into the city and laid siege to it. Finally, in January 1511, Christian IV gave in and made serious concessions for peace. Frederick was not content with the Orkneys; he demanded and received reparations for the war and forced Denmark to release the republic of Gotland; Mecklemburg swore loyalty to him as well. And all for a few acres of land...

Typically of Frederick, the war had been planned and executed brilliantly but impersonally. There was a tinge of embarassment about the war in London. Charles II had indeed claimed the Orkneys, but it seemed cruel to have treated the Danes so poorly in victory. Troop morale was at an all-time low. Then a saving grace, quite literally. In England, a saint performed a miracle, and the people saw this as a sign that the peace had been blessed. Denmark seemed convinced by this as well; the following year, Christian IV ceded Albershus to the pope, ending over thirty years of the popes being landless.

The Danish campaign would not be the last adventure for Frederick's armies. Frederick had abandoned the defensive posture of his father and now sought out opportunities to test his men in battle. In June 1514 Portugal declared war on the infidels in Morocco over their piracy in the Meditteranean. Not wanting to lose Britain's most stalwart allies, Frederick sent an expeditionary force to Tangiers. Although all of Iberia was at war with them, none of the Christian powers would spare more than a regiment to invade the deserts of Morocco, and 4,000 British found themselves the only real force preventing a total defeat by the infidel. Despite their small numbers, they consistently outfought Berber armies of twice their size, only to lose their conquests to their hordes as soon as they left. Under those conditions there was no chance for victory without a full-scale invasion, which Frederick categorically denied; he had no aims in Africa and no desire to spend more money on Portuguese war aims. The outnumbered expeditionary force marched on Marrakesh in an eleventh-hour bid to end the war and suffered their only defeat against 4:1 odds - and even then, the battle had been close. Frederick recalled his men and let the Portuguese end the war in a stalemate. Still, he had proven to the Portugese that he could be trusted, and more: the adventure had planted the dangerous idea in his mind that British power could overwhelm the infidel outside of Europe.

From Humble Beginnings

Some of the greatest events in history have come from the tiniest of events. Two such events happened in short succession during Frederick's reign.

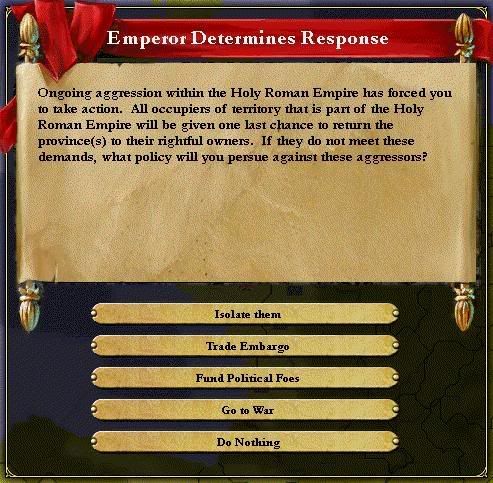

Thanks to their claim to Mecklemburg, the House of Lancaster was considered to be a ruling family of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1515, the emperor died and the seven electors of the empire met to choose a new emperor. The electors were wary of France and glad to see Denmark humiliated; the United Kingdoms would not only be a bulwark against these enemies, without having any designs on the empire. Having heard his reputation, they apparently thought he would be a docile, senile emperor who would leave them alone and ensure

de facto independence. The result was his election in February 1515 to the royal purple.

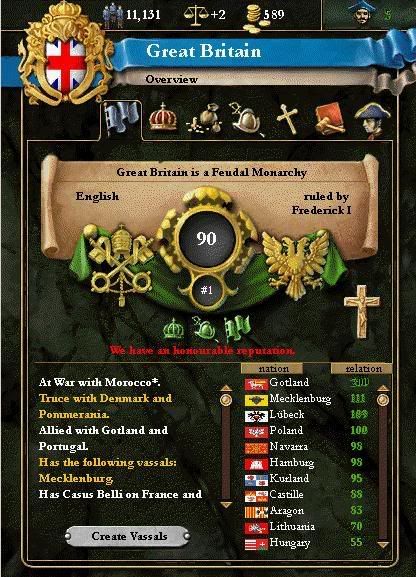

Frederick I at the height of his influence

Frederick was a reluctant emperor, but he did carry out his duties as emperor

Frederick became the Holy Roman Emperor, just one more title for the high king, but one that also made him the defender of the Catholic faith in Germany. The king had many interactions with the church. He was a church-going Catholic but never seemed to grasp theology; he regarded the church rationally, verging on heresy. A short year earlier the pope in Rome had passed away and during the conclave Frederick had moved Heaven and Earth to make sure his personal confessor (the future Pius X) was elected. What he would have done with a pope he knew so well can only be imagined, for Pius X reigned only nine days, from June 20 to June 28, 1509, making him one of the shortest-reigning popes. Frederick's diary was characteristically blunt:

"July 7, 1509. Breakfast: Toast with peach marmelade and small beer. Stain on pillow. News from Continent: French raise taxes, shortage of pepper, pope dies. Lunch: Roast Boar with cherry sauce, watered wine."

At another time, he encouraged the pope to canonize Saint Albus in Fife simply so that he could gain higher tolls from pilgrims; unfortunately, this was the tail end of his influence with the church. Elected emperor, Frederick was seen as too powerful by the pope, who withdrew his support. This was felt in various ways, but none as clear as the simony that grew ubiquitous in England for the first time in generations.

But the real story of his time was still to be told. In 1514 the Swedish philosopher Franz Leopold Bischofberger published a new translation of the bible, making use of the older sources from the fall of Byzantium in the east. This new translation showed, page by page, Bischofberger's translation against the Vulgate translation used by the Catholic Church. The differences were astounding, and disturbing. Now, any learned man could see plainly that the church was capable of error. If it could err on something as basic as the bible, could it err on doctrine? The answer was to follow suddenly, when on January 15, 1515, a date that will live forever, Samuel Dempier nailed 95 theses to the wall of the Hamar church. The Danish monk was protesting a number of excesses in the church, from incompetent priests to the practice of selling indulgences for money. Unlike previous theologians, Dempier took the unusual step of writing both in Latin and in ordinary Danish. Even the common man of the street could walk by and read his arguments - and many agreed with him. Although few realized it at the time, something momentous had occurred in Denmark: the Protestant Reformation had begun.

The Church of England

Reaction to the Reformation was uncharacteristically swift. The Council of Livland opened on July 28th, 1516. The Council was not called to deal with Dempier's heretical theses, but the document (meant to be a single item on the schedule) quickly took over the council. Before anything could be decided, however, Muscovian armies once again invaded Scandinavia and the council had to be disbanded. Few realized it at the time, but the chance of dealing with Dempier swiftly and with unity passed along with the safety of Albershus.

Several months later, the Imperial City of Frankfurt openly sided with the so-called Dempierans. Without close imperial control, the city had been swept up in religious fervor. They suffered the consequences shortly thereafter when the entire city was excommunicated, but slowly the new heresy was spreading across Europe. Seeing Frankfurt's example, few dared to openly side with Dempier. As late as 1519, only a handful of provinces had converted to the new faith.

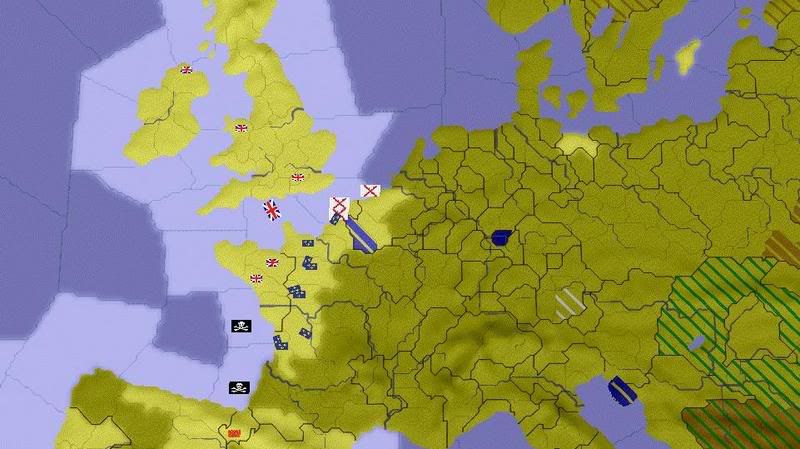

In 1517 the Reformation was still toothless

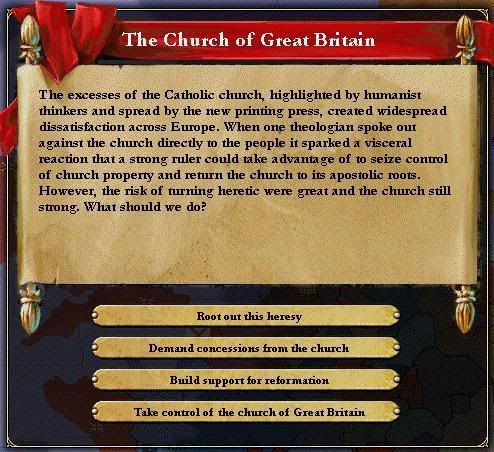

By 1517 the heresy had been translated into English and already some were openly calling for reform - even in Parliament. All of a sudden, Frederick's "eccentricities", which had seemed harmless, were worrisome. Would he decide it was more rational to side with the heretics? As emperor and high king of the United Kingdoms, he had the potential to lead Europe away from the church, which was already vulnerable - and with Parliament curtailed and Frederick capable of exerting autocratic control on a whim, many looked on in fear or hope when Frederick read the tract.

There were many proposals for dealing with the heresy, but the decision rested in the king's hands alone

The king's diaries are once again revealing. Frederick closeted himself for days on end while he decided, screaming at the Archbishop of Canterbury when he tried to intervene. In the end, Frederick made his decision from pure reason divorced from faith: he chose to remain Catholic.

By staying true to the church, Frederick ensured his good graces in the pope's eyes and remained a power in the Curia; he also recognized the massive upheaval that would be caused by converting when the people had not been convinced of the new heresy and feared what an excommunication would do to his still-shaky international relations. When he spoke to Parliament he delivered a blistering attack on the new faith, probably penned largely by Hugo Grimes, his personal confessor. In return for this sign of support, the pope named Frederick "Defender of the Faith", a title he would add to his growing list...

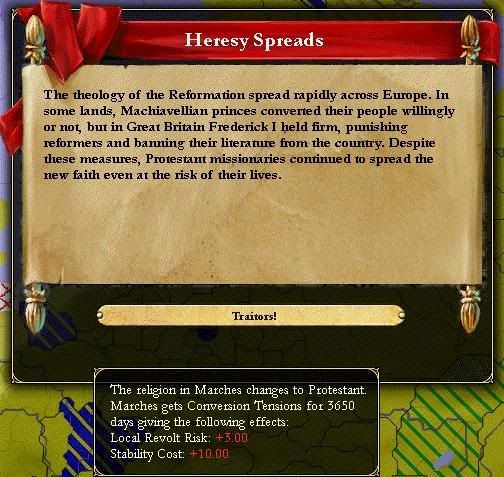

Despite this honor, Frederick reacted with sanguine when heresy began to spread in the United Kingdoms only a few years later. In 1519 the Dempieran faith had spread to the Marches as the English tracts spread across the isles. Rather than burning these heretics at the stake, Frederick did little more than write it down in his journal along with everything else that had happened that day.

But although Frederick's decision had given the Catholic Church time to react to the heresy, it did not save it. Only a few short years later another great power would take up the cause of the Reformation, and Frederick once again made a supremely rational decision that would shake Europe...

The first major centre of heresy in England was in the north of England

The United Kingdoms at a Glance in 1520

Treasury: 745 million ducats

Estimated GDP: 574.8 million ducats

Standing Army: 29,000 Landsknechten and 10,000 knights

Reserves: 56,000 (thanks to the empire)

Royal Navy: 11 caravels, 3 small ships and 4 transports

Prestige: 1st highest (89.4)

Reputation: Honorable (0/18)