[

RGB: I've managed to get enough inspiration to finish everything and get the editing in... I think I have gotten it right, at least. This is certainly the longest update of any I can think of in this AAR!

Deamon: Explode indeed. I'll only be able to go into the War of the Spanish Succession here, but there's also a war between Sweden and Finnland going on at the same time, as well as one with Brandenburg, a newly independent Prussia, and Lithuanian rebels all against Poland. In other words, almost all of Europe is at war at once. It's a mess, and the rest of the century isn't going to be any better.]

Despite large lobbies in all the nations of the League of Augsburg calling for them to intervene in the war, they very nearly failed to do so. Rebellions had, in the previous two years, flared up in the Helvetian Confederacy's Italian territories, with Austrian support, and the matter very nearly resulted in full-scale war. Support for the Babenburg candidate in such a situation was a divisive matter, and Helvetia attempted to veto it. Baden and the Palatinate, for their part, were single-mindedly lobbying for war with France for the simple reason of driving them out of the Holy Roman Empire. Britain and the Netherlands, however, were somewhat more uncertain, and neither wished to tear the League apart on the matter. It seemed as if the League might respectfully decline to become involved and allow the nations involved to work it out for themselves. As the war itself broke out, however, Austria, eager for support, agreed to withdraw its support for the rebels; Helvetia was losing the fight on that front in any case.* With that matter settled, the League declared for the Babenburgs.

Britain's plan had been in place since before the Siena war, at least in its general shape, and was the product of Emperor Henry himself. Unlike previous wars against France, where Flanders was the main battlefield, the British would dangle the rich region before the French armies as a trap to draw them in. Henry sent his own uncle, Richard, Duke of York, to take command of the Army of Flanders and attempt to delay the French army as long as possible. He was likely to be vastly outnumbered, but this was entirely Henry's plan; the more French were tied down there and in Upper Lorraine, the fewer were available for his main strike. All Richard had to do was delay as long as he could, and prevent Flanders from falling for a year or two at the most before, hopefully, the heartland of France, Blois and Paris, would be open to the other army.

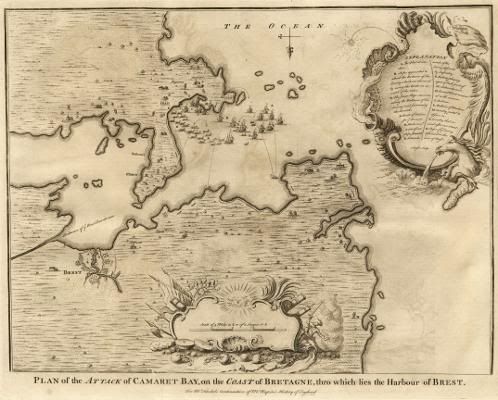

Although the plan predated Marlborough's rise, Henry knew precisely the man to command said army by this point. As with the Italian campaign, he would board ships and launch an invasion by sea; this time, however, the target was much closer: Bretagne. Welsh and Cornish regiments were disproportionately represented in this army; it was to portray itself as an army of liberation, freeing the Breton people, who had faced centuries of French pressure upon their culture. Henry, of course, pointed out that the British crown still carried with it a claim upon Bretagne (as well as France itself, although Henry knew he could not press that one). The Welsh and Cornish, schooled in the speech of their continental cousins, would proclaim the return of the distant heir of Alderic de Cornouaille and attempt to rally the Bretons behind them.** By the time the French armies realised what was happening, Henry hoped, Bretagne would be solidly in Marlborough's hands and he could advance towards Blois.

As the plan had already been in place for quite some time, both the navy and the armies moved swiftly. The Royal Navy quickly took control of the Channel, a fact that the French navy did not even bother to dispute. As soon as things got in motion, however, a major problem appeared. The original plan had been for York to hold in Flanders and try to bog the inevitable French invasion down; however, of his own accord, he advanced into Picardy in a misguided attempt to further draw the French into the area. York's army was professional, and with 25,000 men outnumbered the 10,000-man French army in the area. York's move had moved him away from supply, however, and he failed to keep his army together, at the end even putting the Somme between the two parts of it. His opponent was Claude Louis Hector de Villars, a skilled commander, who took quick advantage of York's error. At Fricourt on 7 December, and the aptly-named Misery on 9 December, Villars defeated both portions of York's army and sent him back to Flanders.

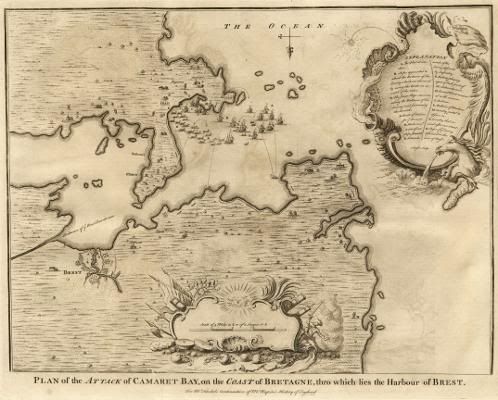

The British navy's plan for the sea portion of the assault on Brest; south is at top.

Marlborough, of course, could not hear of the defeat, as his men were already crossing the Channel. His army landed at Plougonvellin on 20 December, and set siege to the city of Brest, the British navy also pushing towards the city's harbour. The shocked French defenders put up a token fight, but the siege lasted less than a month; on 11 January 1701, Marlborough's well-trained army, with the help of his ships' guns, assaulted the fortifications and took them with little trouble. The most telling sign of the French defenders' surprise and low morale was the low losses

they took; more than one bastion surrendered without a shot when it became obvious they had no chance of victory. Among those captured was the famed Marquis de Vauban, sent to the city to help build up its fortifications; King Louis had obviously not expected so early and so large an attack there.

When the British army sent out its proclamation of Breton liberty, the response was better than Marlborough or Henry could ever have hoped. Bretons turned out by the thousands, eagerly chattering with the Welsh and Cornish despite the difficulty the latter had in understanding, though thanks to preparation translators were easily found. Flags bearing the ermine and stripes of Bretagne were quickly and gladly sewn to fly above the city. Supplies for the winter were cheerfully sold, although this was not so much of a concern as British ships now sailed regularly between Brest and southern England. Hundreds of able-bodied men volunteered to serve under Marlborough's command, allowing him to place a full-sized garrison in captured fortifications. Despite the winter, Marlborough was now in friendly territory, and he could press his advantage while the French armies were still out of position, reaching the Breton capital of Rennes on 1 February. The French there were more ready for an attack, however, and Marlborough was forced to settle down to sieges of the various fortifications in eastern Bretagne.

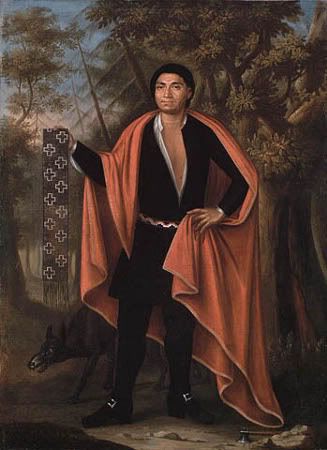

Among the Bretons who continued to flock to Marlborough's army as he marched through the Breton countryside was a singular woman: Louise de Penancoët de Kerouaille, a Breton noblewoman who had previously been the mistress of Prince Charles. Although appointed Duchess of Aubigny by King Louis, she was deeply in debt and hoped that being a Breton would allow her to profit by switching sides. Marlborough was understandably concerned, but decided to refer her to Emperor Henry anyway. De Kerouaille's appearance was, Henry knew, either a blessing by giving him a Breton figure for his hopefully new subjects to rally around, or a danger as the ambitious woman could tear the whole Breton expedition apart, politically. Although there were no credible rumors of an affair - de Kerouialle was fifty-one years old by this point, and Henry apparently entirely uninterested - she was universally reviled around the British court as a French Papist and undue influence on Henry. Henry carefully kept her out of the way while the war continued.

Louise de Kerouaille, by Pierre Mignard (1660)

As Marlborough continued to attept to reduce the fortifications around Rennes, the main French army, in a severe strategic error that played exactly into the British plan, took the bait and attacked Flanders. In command this time was Francois, Duke of Villeroi, who showed the same impetuosity and carelessness that York had displayed previously by advancing before most of his army was in place. York, for his part, had learned from his error, and regained the confidence of his soldiers by surprising and smashing an advance force at Moorslede. Believing the British defences in Flanders proper to be unbreakable, Villeroi decided to make another attempt to the south. In mid-March he began his march into Wallonia, and for the next month he and York maneuvered around Charnoy and Brussels. A skirmish and British victory at Waterloo south of Brussels made a direct attack on that city unreasonable; Villeroi moved further east, retreating first to Louvain and then to Namur, from where he struck north again. On 14 April, he finally blundered blindly into York's army at Ramillies.

The field was mostly flat and open; Villeroi could see that the two armies were approximately equal in size and composition. Thinking he could goad York into an error, he set up with one flank on the swampy ground along the Mehaigne river, the other quite a distance past York's flank north of Ramillies itself, across a swampy stream known as the Little Geete. He hoped to use this threatening move to force York to try and push through before he was outflanked. York, however, noted that this stretched Villeroi's line thin at several points, and obliged with the attack - on his terms. George Hamilton, Earl of Orkney, the commander of his right flank, surged forward and broke through across the Little Geete with little trouble, as the French had only just arrived in their positions and were not quite set. British cavalry on the other flank had the same success, despite that flank being better set, and pushed the French away from the town of Taviers.

The Emperor's Horse pushing through the French right at Ramillies

Villeroi himself insisted upon holding his ground on the left-centre of his line, even as the rest of his army, seeing the flanks torn to pieces like wet paper, pulled back, broke, and began to flee. His stubbornness only made a bad situation worse; York's flanking cavalry swept across the field, and before the French centre could escape, began riding behind them. The French panicked, crowding themsevles into a smaller and smaller area to try and escape, to no avail. Villeroi and half of his army were captured, and the rest scattered in various groups returning to France. York realised to his own amazement that he had, in his attempt to push the French army backwards, achieved the double envelopment sought after by all commanders ever since Hannibal's victory at Cannae. The rest of the French army that was still gathering in Flanders and northern France was now exposed and still in small groups; York was able to take revenge for his early defeat by taking them out in detail.

The Battle of Ramillies. Each line is c. 1000 men.

The events of the battle put the whole French battle plan into ruin. The only other army in France with any sort of cohesion was collecting men with which to assault Marlborough's advance; believing that the Channel was the British general's main goal, however, Louis put Villars in command and hastily ordered him to Flanders to prevent what he believed was a threat to Rheims and Paris, and perhaps Blois afterwards. The besieged garrison at Rennes, slowly realising that relief would never come and that the Breton population of the city was growing ever more restless, surrendered on 11 July, leaving all of Bretagne under British control. Marlborough himself marched northeast to Normandy, spending the next three months dealing with several forts over the region and setting up a new supply line that would be shorter than one extending all the way from Brest.

Outside of France, Louis was having no more luck. The Duke of Vendome was attempting to hold Lower Lorraine, but he faced two skilled opponents: Ludwig Wilhelm, King of Baden and Holy Roman Emperor, and his cousin Francis Eugene, Prince of Savoy-Carignan.*** The two had no less a goal than the complete conquest of Lower Lorraine, but Vendome made every effort to slow them down and hold the region until peace could be obtained. He did succeed on delaying the invasion for nearly a year, but at Haldorf on 20 September 1701, Emperor Ludwig and Prince Eugene broke the army and pushed it back all the way to Muenster. The Holy Roman Emperor became noted for his bright red coat on the field, gaining the nickname of "The Red King"; as he continued to advance further and destroyed the remaining pieces of French resistance utterly, he became known as the "Shield of the Empire".†

A bust of Ludwig Wilhelm von Zähringen, the "Shield of the Empire"

The conflict in America was not organised on either side; minor border incidents had been occuring for half a century before the War of the Spanish Succession broke out. Both sides mostly limited themselves to minor raids across the border; as 1701 went on, however, it became increasingly obvious that British raids were occuring more often and pushing further into French territory. On 18 June 1701, a raiding force viciously sacked Savanne, the capital of the French colony of Louisiana. Among the raiders (and likely contributing to the brutality) was a privateer named Edward Teach, later to make his name as the pirate Blackbeard. Whatever the case, no force quite large enough to permanently occupy French territory could be raised, but the Portuguese were able to seize a few Caribbean islands and maintain control over them.

These victories effectively shrank the region of conflict to northern France itself. York defeated several attempts by Villars to push into Flanders, and finally, on 17 December 1701, laid siege to Calais. This was another potential gain from the war for Emperor Henry, as he also held claim to the city, and it served as a useful strategic port, the nearest point in France to Britain. York made several assaults upon the city, using both his army and the Royal Navy, but all were repulsed. The bravery and tenacity of the inhabitants of Calais, despite being outnumbered and surrounded, became legend within France. Despite continuing to besiege and assault the city, and despite the lack of any French relief force able to come to its aid, York was never able to capture Calais.

Marlborough, meanwhile, had begun marching south from Rouen, feinting a march up the Seine towards Paris before striking southward to Blois. No force large enough to significantly delay Marlborough could be brought together, and on 14 January 1702 the British army marched into the French capital. Louis did not capitulate yet, however, and a final army, under Villars' command, appeared near Paris. Villars was outnumbered, but could expect 16,000 more men from the south by mid-year; Marlborough would have to strike immediately. This he did, and after several skirmishes they met at Cergy on 10 March 1702. The result was not in doubt, and Marlborough did defeat Villars' army. However, it was not an easy victory, with Marlborough's army taking a surprisingly large number of casualties; a rumor that Marlborough himself had fallen went around the battlefield at one point.‡ All Marlborough could do was occupy Paris and keep the French from retaking the captured cities of northern France.

By this point, France had already been forced out of the entirely of Lower Lorraine, and the Count Palatine had captured Cologne. Although Spain was not much involved in the war, as the disputed succession had caused a practical civil war there, even that country was beginning to stabilise and advance along the Mediterranean coast of southern France. An armistice between France and the League of Augsburg was agreed to in May of 1702, but peace talks took another year after that, during which time the annoyed Duke of York was forced to lift his siege of Calais. The severe losses taken by Marlborough at Cergy and the failure to capture Calais put France in a surprisingly good position as the leaders of the various European powers met at Utrecht in the Netherlands. That France had lost its German territories and the Babenburg candidate would take the Spanish throne was taken as a given by both sides, and the British claim to Bretagne was agreed to quickly as well. Although the colonial militia had finally taken Savanne, France insisted upon keeping it as its only access to the region of Louisiana, and that part was dropped. Other attempts to bite off various bits from France had various amounts of success.

Verdun remained in French hands, as France claimed it was a necessary border fortification. The particularly fluid borders of Flanders were not moved an inch, and Helvetia, despite constant fighting along its border with France, only gained a small portion of land in Savoy. Spain gained a small sliver of land near the Catalan border town of Rossello. The final Treaty of Utrecht was agreed to and signed on 18 March 1703; the ultimate stated goal of the treaty was the preservation of a "balance of power" in Europe that France had overturned by its attempted expansion. The war was a clear victory for the Grand Alliance against France, as would be expected from the massive advantage in numbers they had, but French morale was far from broken, as Calais and Cergy became symbols of French tenacity and ability against impossible odds. Still, the British armies could return to their own country as victorious heroes.

__________

*The independence of the republics of Mantua and Milan would be recognised in the Treaty of Utrecht.

**Although the Cromwells could not, of course, claim direct descent from the de Cornouailles, they counted on the fact that Breton patriots would not be too concerned with that fact, as the British crown had been possessed by the true heirs of Alderic for nearly four centuries. King Louis, for his part, allowed James Borcalan (the now-dead Prince Charles' brother) his claim to Bretagne, but this produced no loyalty among the Bretons.

***Despite the name, he was not fighting on behalf of Savoy but of the Duke of Austria.

†Sadly, a full account of the Holy Roman Emperor's campaign in Lower Lorraine is well outside the bounds of this account; for those further interested, there is no small number of works on the subject.

‡The rumor gave rise to a cruelly mocking French folk song ("Death and Burial of the Invincible Marlborough"), very popular during the 18th century as a sign of defiance against the British.