[

RGB:

1. Nope, and he's going to cause all sorts of fun, too.

2. It really doesn't effect as much as you might think. No War of the Austrian Succession, for one, partially because Prussia

already has Silesia.

3. Not too much this time around. At least they'll reach the Pacific alright.

4. Ah, yes, they're certainly making up for Germany in that regard. And it'll stay that way for a little bit, too.

5. I like that one myself; Taugu was important at this time, but they've managed to get out even further than usual. And they've some staying power.

6. Ah, you know how those things are.

7. I mentioned it in passing, but the British helped support the Inca, and they fought off the Spanish several times. Less "left them alone" and more "tried to conquer them, but failed spectacularly".

Morsky: The Jacobites aren't gone yet, though. And as for the last bit, they'll be quiet for a little bit, actually.]

Despite the fact that the war had been planned for some time on Britain's part, the world-spanning nature of the intended campaigns caused a bit of delay in moving everything into place. In fact, the first fighting of the war was initiated by Spain, not Britain, as on 23 March 1737 they sent a force into Belize. The Baymen were unable to stand up to the force before them, and slipped north and then west to gain the aid of the King of Peten. On 2 April the Spanish force reached the harbour at Belize Town, finding anything valuable carried off by ship to the Caymans and their supply lines threatened by Itza and Baymen raids. The invading Spanish were forced to withdraw, burning what they could, and leave the region to Britain, making no further effort in that area.

Not long after, fighting began in the main area of importance for the British, the southern end of Columbia. A force of 4100 men had begun marching south from Fort St. George on Chile Island, aided by a seven-ship naval squadron* which kept them in supply. The expedition was under the command of the leader of the squadron, Vice Admiral Edward Vernon, a veteran of the Battle of the North Channel against the Icelandic fleet a decade previous. Vernon's force reached its first goal, the "Rey Don Felipe" colony at the southern end of the American continent proper, on 10 May, burning it and forcing the Spanish colonists to flee. A small colony, named Sandy Point, was set up by some of the more adventurous in Fort St. George and Ushuaia. Less than a month later, much of the Spanish garrison of the La Plata colony appeared, 6000 men strong, and on 16 June 1737 the two met north of Sandy Point.

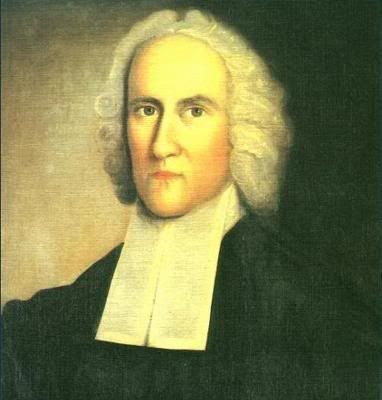

Admrial Edward Vernon, by Thomas Gainsborough (date unknown)

Vernon easily chased off a couple Spanish ships attempting to support the attack, and set the infantry along a low ridge. His men were just enough to anchor one end on a hill overlooking the seaside cliffs, and the other end on the wooded slopes of the mountains around 1400 meters inland, with reserves to plug any holes the charging cavalry might cause. The Spanish commander, Jose Antonio de Mendoza, felt confident that his cavalry could charge across the flat land between him and the British army; he sent them to take the low hills, with a small portion of them supporting the infantry on an attack against the British centre. Unfortunately for him, however, his men did not stick well to the carefully-unfolding plan he had set before them. The cavalry, feeling the battle to be well in hand, immediately charged with little regard to proper order, leaving the infantry to try and catch up to them.

On the Spanish right, much of the force had to route around or through a stand of woods, and they were unable to regain cohesion due to their fast pace before reaching the British left. Vernon's frigates, meanwhile, though they could not elevate their guns enough to reach the tops of the cliffs, could come close enough to pepper the attacking cavalry with rifle fire, doing little damage but giving them the disconcerting feeling of being outflanked. As they reached the foot of the hill, the front ranks were mowed down by a musket volley; when half of them stopped, the other half ran into each other, creating a mess of men and horses that was entangled perfectly within range of the Land Pattern muskets. Aim was not a concern; the British could aim within the tangle and be sure of hitting something Spanish. After taking horrendous casualties the attackers were eventually able to extract themselves and flee back, all hope of attack ruined.

The other flank fared better, but not by much. The hillside slowed them somewhat and broke the attack into several small waves, but they were at least able to reach the British lines in good order, if not at proper charging speed. Some pushed within the British lines, only to be brought down by reserve bayonets. As one wave was pushed back, the next charged through their fellows, often trampling those who had been unhorsed, to attempt to take advantage of the weakening of the British line; extra reserves had been rushed over from the unthreatened centre, however, and met the new charges with more musket fire and bayonets. At one point the British were even able to charge themselves and capture a few hundred Spanish. The attack on that flank cleared a quarter of an hour after the other, leaving only the Spanish centre, composed of the infantry and a thousand of the cavalry which had failed to advance, intact. That force knew better than to attempt an attack of their own, and pulled back north.

The Battle of Sandy Point. Each line is c. 250 men.

With the main Spanish army in the region broken, Vernon was easily able to advance northward. The Spanish were never again able to send a force capable of driving them off; Patagonia had been secured. However, his force was unable to assault the La Plata colony itself, and the hoped-for Portuguese attack from the north was turned back several times. Despite that, Sandy Point was hailed back in Britain as a great victory, and Vernon as a hero. Green's Lane in Notting Hill was renamed Sandy Point Road, and locations in Edinburgh and Dublin recieved the same treatment. One of the more important Virginia aristocrats, Captain Laurence Washington, was a commander of marines at the battle, and named the family mansion of Mount Vernon after the admiral. At the celebrations in London, Emperor Thomas commanded the staging of an opera named

Alfred commemorating British military prowess; the centrepiece was the rousing "Rule Britannia", the famous paean to Britain's growing naval dominance.

The war was far from over, however; it merely shifted focus. While the New World was mostly dealt with (some minor fighting in America went back-and-forth along the border and achieved nothing), the Old saw war once again. Spain had brought the Netherlands into the war, and in mid-1737 a Dutch army under the Prince of Waldeck advanced into the ever-embattled Flanders. Douglas-Hamilton had died earlier in the year, and his successor, the Duke of Argyll, did not perform nearly as well as his predecessor. For a time, it seemed as if the Dutch would secure Flanders and overrun the rest of the British Netherlands; Argyll was quickly recalled and a new force raised.

The commander was an unusual one for a British army: Francois de la Rochefoucauld, the Marquis of Montandré, a Huguenot who had put himself at the service of the British emperor due to persecution in France. His family was an important one in France, particularly his 17th-century namesake, a notable philosopher and writer. Montandré collected his army, integrated it into the one he had inherited from Argyll, and overwhelmed the Dutch at Terneuzen, across the Sceld estuary from Flushing, on 3 December 1737. The 51,000-string British army was the largest in Europe at the time, and the shocked Dutch could only hope to slow them by using their ships in the many waterways crossing Zeeland. This hope was quickly crushed by the arrival of Vernon and the Royal Navy, which bottled the Dutch fleet in the ports of Amsterdam and Horn in the Zuider Zee; Montandré slowly marched northward unopposed, and on 24 April 1738 set siege to the capital of Harlem, which fell later that year.

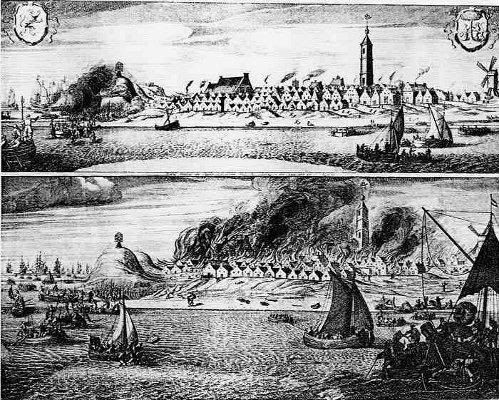

A coordinated attack on 3 February 1739 struck at Amsterdam and Horn, with the Royal Navy blocking escape into the North Sea. The Dutch navy and merchant fleet, unable to escape, was either sunk by the newer, larger British ships, captured (though few were willing to be taken), or burned in their harbours. Many towns and harbours all along the Dutch coast were also raided and burned between mid-1738 and the end of the war. Despite Dutch calls for revenge against such a humiliating loss, they never again developed a fleet capable of rivalling Britain's, and the loss of so many ships crippled much of their foreign empire.

A harbour on the Dutch island of Terschelling burning, in a contemporary engraving

King Louis X of France hosted the treaty as a neutral party, and negotiations had already started while Harlem was still under siege. The first treaty was at Versailles on 21 March 1739, with Spain, handing the region of Patagonia over to Britain; the northern border was defined as the Rio Negro and Nequen River. The second was in Blois, on 2 April 1739, ceding a good portion of Zeeland - all the land south of the Sceld - to Flanders. But although the war had been an overall success for Britain, many in Parliament, and among the populace, were disappointed that the gains had not been greater. None of Spain's Caribbean possessions had been so much as touched, the Yucatan remained in their possession, and Portugal had been too busy fighting off attacks on their European possessions to help take La Plata.

Walpole's main opposition at this time was not the Tories, but the "Patriot Whigs"; aside from the disappointment with the war, his arrangement of the dismissal of another Patriot, William Pitt, from the army was seen as an abuse of his authority. As news came back of the treaties, William Pulteney, the leader of the faction, requested early elections to Parliament. Thomas, seeing that Walpole was rapidly becoming unpopular, dissolved Parliament (enough time had passed since the last election, in 1737, to allow him to do so), hoping that Newcastle would take his place. The Patriots, however, had broad support with the middle class, and took easy control of Parliament. Spencer Compton, the Earl of Wilmington, became the new Lord Treasurer; Pulteney (soon after made Earl of Bath), however, was regarded as the main figure in the government, and thus the Prime Minister, one of the few times the two titles were held by different people.

William Pulteney, Earl of Bath, by Jean-Baptiste van Loo (c. 1745)

The early 1740s seemed to herald a better time in Britain. Bath's early ministry oversaw peaceful economic expansion, especially in the British colonies and trade with the Portuguese colonies. At home, opposition to the Reform Act and Recusancy Act had calmed, and the Jacobites were oddly quiet. In 1742, the East India Company launched an attack upon the Marathis, in an attempt to seize the ports of Surat and Bombay. Several times, the cities were taken and then lost; only in 1744, when James Wolfe was given command of the invading army, was Bombay taken permanently (3 June 1744) and Surat put under a long siege.

Britain's attention was quickly turned back to home, however. In 1744, several chiefs of the Scottish Highland clans sent a message to France, asking for men and supplies to aid an uprising. The "Wild Geese" of the

Brigade irlandaise, a unit of Irish Catholic exiles fighting for the French army, arrived on 2 August 1745, along with Charles Edward Borcalan, son of the still-living "Old Pretender". Around the core sent from France, "Bonnie Prince Charlie" collected 25,000 men overall from both the Highlands and Lowlands - an astounding force in such a short time, showing that the rebellion was long in the planning - and set siege to Edinburgh. Panic set in as it seemed all of Scotland might declare for the Borcalans, and only Wade's relatively small "Black Watch" was in the immediate area. The Northern Secretary, William Stanhope, Earl of Harrington, quickly requisitioned the Army of Flanders from his Southern counterpart, still Newcastle; the two got in a heated argument over the matter, wasting valuable time as Edinburgh threatened to fall.

Bath and Wilmington finally forced Newcastle's hand, and the Army of Flanders began north in February; before it could go into action, however, Emperor Thomas died on 18 March 1746. The loss of the Emperor when a pretender army was on British soil was a political disaster; supporters of the Borcalans and the Cromwells began rising up and fighting all over Britain. It had taken a century, but the Borcalans had finally returned the empire to a proper state of civil war.

__________

*The sixty gun HMS

Dreadnought and fifty gun HMS

Antelope, with five 24-gun frigates. With the lack of available bomb ketches in the region, the former two were intended to help perform shore bombardment duty against any Spanish fortifications, with actual naval combat unlikely, at least against ships the frigates could not handle.

If the Emperor wants to shag a feisty Mediterranean lass, it's his bloody prerogative!