El Pip said:

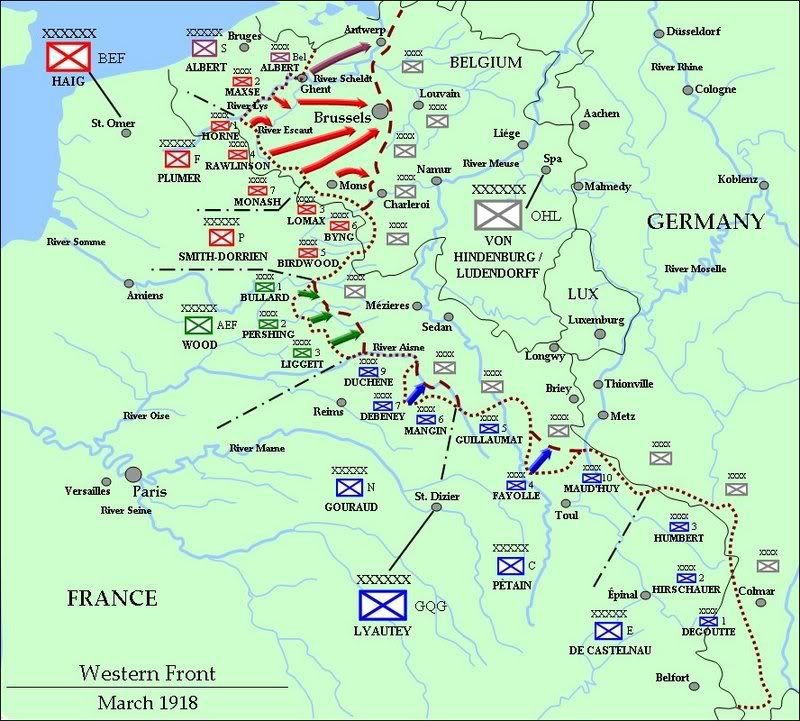

Once again we see the wisdom of Haig, dishing out to the German's a damn good thrashing. We also see the foolishness of Wood and TR in insisting on the AEF remaining independent. Those men would have been far better used as reinforcements for British units than frittered away. Such are the demands of politics and allied warfare I suppose.

Whilst I give Bulow fulls marks for his brass neck peace offer of 'We'll go home and that's it' I have a feeling it will be laughed out of the Foreign Office. Hopefully.

To be fair, the units comprising the AEF were attached to British units before being grouped into independent forces.

The reaction to Bülow's plea is in the next update!

Vann the Red said:

Haig's strategy vindicated. I am certain of the American response to these terms, confident in the British response, and most interested in the French response. Smahing update, Allenby!

Thank you ever so much!

SirCliveWolfe said:

Masterful once again Mr A.

It seems that this war... and therefore this AAR is nearing it's conclusion

I think that the erms will be rejected, we shall see a repeat of what just happened in the autum and a full surrender be Germany in...erm... well the 11th of November 1918 seems like a good date

Don't think I am going to stop just as soon as the war is over.

There is far too much to tidy up afterwards to allow that.

Kurt_Steiner said:

Germany is breathing its last gasps, methinks. Poor Kaiser, poor Hindenburg, poor Luddendorff... They'll have to swallow deep down the Allies condition of peace along with their pride

Like any good man, the Allies will ensure that the recipient swallows instead of spits.

TheExecuter said:

Interesting move by the Germans to cope with the military failure. Entirely logical...in fact, each member played his role to perfection. The military men in focusing on winning the war, and the emperor on the long-term status of the Fatherland. I'm curious, is this how Germany eventually surrenedered in our time line? Seems like it, but I am not a proper WW1 scholar.

Looks like the light has appeared at the end of the tunnel. Unfortunately for the Germans, it is the approaching train of defeat. For the allies...it is the approaching train of 'what do do with the spoils!'

Well now, Germany has not surrendered yet! If these terms are turned down by the Allies, then get ready for a last ditch defence of the Vaterland and the continuation of the war through the summer!

TheExecuter said:

Thanks for spoiling us lately with updates sir. How is TGW2 coming along? Are the problems with the Russians fixed yet?

1914 has barely progressed at all in the past month and a half - I have not really worked on it at all.

The Russian revolution problem was fixed some time ago - the biggest difficulties now are AI-orientated and I see no solution.

Vincent Julien said:

The French will certainly tell anybody bearing those terms to sod off and I imagine that the Americans and the British will cultivate a similar response - over three years of punishing warfare, with Germany on the ropes, for a status quo peace? Not on your nelly jerry. I only hope that Bülow correctly views this as a basis for negotiations rather than a 'quick fix.'

Part fix, part stunt could be one interpretation. Although it could also be a basis for negotiation if one sees that Bülow is attempting to put the subject of peace on the agenda whilst hard bargaining at the same time.

Prufrock451 said:

Strike now!

The German high command must realize that while the loss of Valenciennes is a blow, soon thousands of Allied troops will arrive in the region bloodied and exhausted. They will derive little benefit from the Hindenburg fortifications and they will have no time to entrench as long as German forces in Belgium strike immediately with everything they've got.

That should make the Allies a lot more amenable to negotiations.

Yes! Assuming that the Germans are able to summon the numbers, the firepower and the morale to mount an effective counterattack. But I suppose that anything is possible if there are weakpoints in the Allied line.

Lord_Robertus said:

And so 4 years of blood, sweat and tears draws to an end.

It's been an interesting ride

You're expecting the Allies to accept the German terms and call it quits already?

...or do you see it as the beginning of the end?

There is still a lot that could happen.

aussieboy said:

At the very least, Elsass-Lothringen will be ceded to France, though perhaps reparations are definitely in order. No cession of Westpreussen und Posen to the Poles, though - we don't want to completely humiliate the Germans, just weaken them like the French post-Vienna.

It would depend, to a great extent, on how strong the Poles are - and, of course, what kind of truce is agreed to in the first place. Compromise over Eastern Europe?

Dr Rare said:

The TGW 1.1 mini-mod v.3 will be released soon and lots of new TGW sprites!!!

Hurrah!

Vincent Julien said:

P.P.P.S, I love the fact that the Serbs are now defending a whole stretch of Austro-Hungarian territory.

Yes, it is rather an irony! Although it would be pointed out to the most Austrophobic Serb that it is simply a form of forward defence.

Lord E said:

A very fine attack by the Allies and especially by the British army. I see that the British sure has learnt a lot from their latest advances and now they sure are doing very well when they attack. Interesting to see that the Germans are interested in peace, but I fear that if the politicians try too much they will have to face the army staging a coup.

Shall be interesting to see how all this turns out…

Thank you, E-man!

Yes, don't discount the possibility of a split between civil and military authority and the latter choosing to lock the former out of governance entirely. Ludendorff still has a great deal of power.

Sir Humphrey said:

Great update there, really great stuff. A terrific advance, although the American's seem to have gotten a bloody nose in the process, but then again in time.

Thanks! Quite right, the AEF is bound to improve the more it fights. It is fortunate to be taking on an enemy that is much weaker than in 1914 or 1915.